To the Editors:

In Buenos Aires hundreds of men and women, from all parts of Argentina, stand in line all day and night before the Ministry of the Interior. They seek information about their children who have disappeared. They want to know if they are among the 5,000 corpses that have been found in vacant lots or on the outskirts of cities since March 24, 1976, when the ruling junta took power. Only General Suarez Mason, commander of the first army corps, can authorize them to visit the morgues. He gives permission to only three or four parents to do so each day.

My own family did not have to wait very long. The bodies of my cousin Anna-Maria and her husband Mario Isola were recently found in front of her parents’ house. They were both sociologists; she was twenty-seven and he was twenty-eight. They had been kidnapped six weeks before; their eleven-month-old baby was left in her crib.

Anna-Maria was the granddaughter of my aunt Donna Regina who had, many years ago, come to Argentina as a refugee from Nazism. My aunt was one of the few members of my family to escape death under Hitler, and now her own family is again victimized by fascism, along with many others. It is estimated that some forty persons disappear every day as her granddaughter did; that 20,000 people allegedly critical of the regime languish without trial in the prisons. Parapolice groups take the law into their own hands. Each army corps has its own jails. The books of Kafka and Freud are burned in the universities while those of Rosenberg and Goebbels are sold on newsstands. Bombs have exploded in synagogues and in the offices of Jewish organizations.

What can be done? Are we really as impotent in the face of this new rise of fascism as our parents were over thirty years ago? Must we wait for the plans of the governor of the Buenos Aires province, General Iberico Saint-Jean, to be carried out? He said a few months ago: “First we will kill those who are subversive, then their collaborators, then their sympathizers, then the lukewarm and finally those who are indifferent.”

In Europe a protest campaign is being organized against the World Cup football matches that are to take place in Buenos Aires next year. Americans may not, perhaps, fully appreciate the worldwide attention that will be focused on these matches and the symbolic importance of a campaign to prevent them from taking place there. I hope your readers will support an appeal to athletes and amateurs of sport in all countries to refuse to take part in any sporting events in Argentina, so long as the regime will not free its political prisoners and stop the massacres that are taking place.

I hope they will support a similar appeal to doctors and scientists not to attend the international congress on cancer that is also scheduled to take place in Argentina next year.

At the same time letters and telegrams to the Ambassador of Argentina and to the Carter administration protesting the continuing repression may help to save lives. Unless international protest can be effective, barbarism will continue and triumph.

—Marek Halter

Paris, France

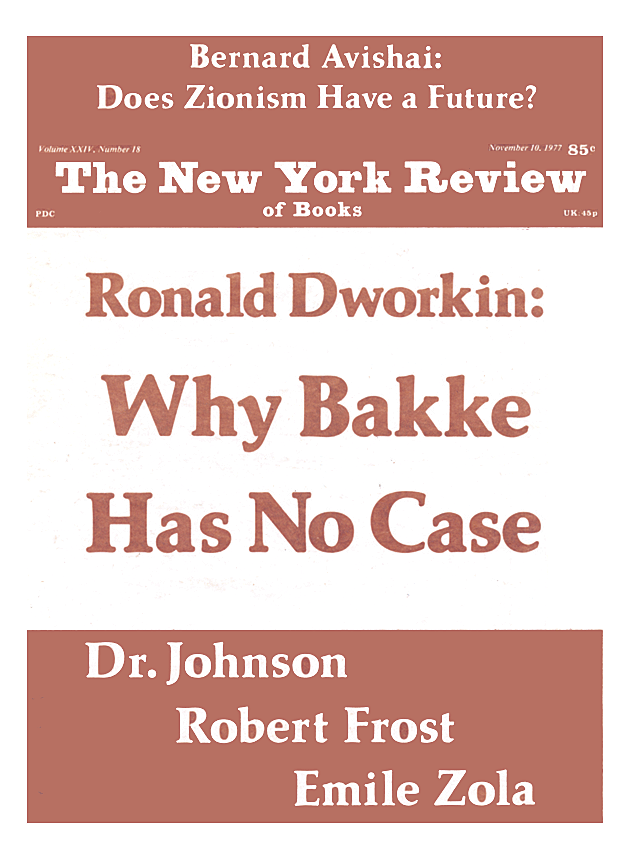

This Issue

November 10, 1977