Amnesty International estimates that there are at least 55,000 political prisoners in Indonesia and that in fact a more accurate total is probably 100,000. They were arrested after the attempted coup in 1965, when a number of middle-ranking army officers tried to destroy the leadership of the Indonesian army and assassinated six senior army generals. The coup attempt was swiftly crushed by surviving army leaders, who charged that the Indonesian Communist Party had been involved. Widespread arrests followed. More than half a million people were killed, and at least 750,000 imprisoned. Although hundreds of thousands of people have been released since 1965, many of these were subsequently rearrested and fresh arrests continue. Furthermore, the total number of untried political prisoners has not changed significantly in the last four years.

Amnesty International believes that the consistent pattern of political imprisonment in Indonesia presents a grave challenge to the concept of international responsibility for human rights. In no other country of the world are so many political prisoners detained without trial and for so many years as in the Republic of Indonesia. A new Amnesty International Report on Indonesia describes the background of political imprisonment there and makes strong and detailed criticisms of the ways in which the constitutional and legal rights of the untried prisoners have been violated.* The report presents clear evidence that Indonesian political prisoners are held under the arbitrary control of the military authorities. Except for the relatively few prisoners who are put on trial, the local military commanders have the power to arrest suspects, to interrogate them, and to permit the use of extreme and brutal torture. These commanders can hold people in prison, use them as servants or for forced labor, release or rearrest them. The Amnesty report is severely critical of the procedures used in the political trials sponsored by the government. But in fact only 800 cases have been heard before the courts since 1965. In conducting these trials, the report concludes, the government is only trying to foster the illusion that it is acting according to established standards of justice.

The vast scale and complex pattern of political imprisonment in Indonesia has given rise to considerable misunderstanding. To comprehend the situation of the prisoners one must refer back to the situation in the early 1960s when, during the regime of President Sukarno, there was an increasing polarization between the left-wing groups led by the Communist Party (PKI) and right-wing political and military factions. In October 1965 a small group of middle-ranking army officers, led by Lt. Commander Untung, a battalion commander in the President’s Guard, captured and assassinated six senior army generals and one other general of lower rank. The attempted coup was quickly suppressed by the army, and President Sukarno’s government was eventually replaced by a military administration under General Suharto, now president. But following the coup a vast purge took place in which more than half a million people were killed by military units and civilian vigilante groups. This figure of more than half a million was given in October 1976 by Admiral Sudomo, the chief of staff of the Indonesian state security agency, in a television interview broadcast in Holland.

In the same interview, Admiral Sudomo also said that following the attempted coup, 750,000 people were arrested. They were held on suspicion that they were involved in the coup attempt. In fact they were victims of a nation-wide campaign mounted by the Indonesian army to destroy the Indonesian Communist Party and other political or social groups which were regarded by the military authorities as showing left-wing tendencies.

The Indonesian Government has abandoned any pretense of establishing before the courts that the tens of thousands of untried prisoners were in any way involved in the attempted coup of 1965. In the eyes of the Government, their only offense was that they were once members of a trade union, or a peasant association, or a cultural association, or of some other organization which existed legally during the period of the Sukarno administration, and which was subsequently proscribed by the administration of President Suharto because it was regarded as communist or left-wing.

Most of these prisoners have never been members of the Indonesian Communist Party: this fact has been readily conceded in private conversations with Amnesty International by leading Indonesian officials. As for those who had been members of the Indonesian Communist Party, it is now clear that the Government has no intention of establishing in the courts that they were personally connected with the attempted coup.

Let us consider one example, of a prisoner who has been recently released—Thaher Thajeb, who comes from a distinguished Atjehnese family. He attended Dutch schools in Indonesia and took a civil engineering degree in Holland in 1941. He was in Holland during the German Occupation and played a part in the Dutch resistance movement. In 1945 he returned to Indonesia and became an official in the Ministry of Communications. In 1955 he ran in the parliamentary elections on the Indonesian Communist Party ticket as a non-party candidate, and he subsequently joined the Communist Party. Later, he became leader of the Communist Party Parliamentary Faction. He was among the very first of those to be arrested in October 1965, and he was reported released in June this year after spending more than eleven years in Salemba Prison without having been charged or tried. No evidence has been produced that he engaged in any illegal acts. The same can be said for nearly all the other untried prisoners, most of whom were never members of the Communist Party.

Advertisement

The case of Thaher Thajeb also illustrates the wide net cast by the inquisition following the events of 1965. His brother is Lieutenant General Syarif Thajeb, who was appointed on October 2, 1977 by President Suharto as Acting Foreign Minister. With Mr. Thajeb released, there now remain twenty-two former members of Parliament in prison in Indonesia.

The Government of Indonesia has, over the years, presented a bewildering array of misleading and inaccurate statistics concerning the numbers of untried persons. For example, the total number of untried prisoners accounted for by the Government in Central Java in 1975 was 5,376. During that same period it was known to Amnesty International that at least 9,870 prisoners were being held in eleven of the main detention centers of Central Java alone. This total did not take into account untried prisoners held in other detention centers in cities and towns of Central Java.

While the official regional statistics reveal that untried political prisoners are to be found throughout the Republic, the figures themselves seriously underestimate the actual numbers of such prisoners being held. There are at least 30,000 more untried political prisoners than the official statistics show. The new Amnesty report documents the unending stream of misleading statistics presented over the years by President Suharto and leading ministers and officials. Recently we have had a striking example of contradictory official estimates of the total number of prisoners held. Last May, official figures released by the Indonesian Government stated that some 27,000 untried political prisoners were then in detention. On September 27, however, Reuter’s reported the following from Jakarta:

National Security Chief Admiral Sudomo has said that preparations have been completed for the release of 10,000 suspected Communist prisoners in December. But he told reporters that 31,000 suspected communists would remain in prison.

The government thus acknowledges that some 41,000 untried political detainees are in prison. According to Amnesty International’s calculations, the true figure is certainly more than 55,000 and could be as high as 100,000.

The Indonesian Government has claimed repeatedly that its treatment of political prisoners is humane and that the conditions in political prisons are reasonably satisfactory. In reality, the conditions in most Indonesian political prisons are deplorable. The supply of food has generally been grossly inadequate. Medical treatment has frequently been nonexistent, notwithstanding urgent cases of tuberculosis and the prevalence of chronic ailments stemming from malnutrition and from over-crowding over an eleven-year period. Many prisoners have had no contact with their families during the entire period of their detention, while in most prisons all reading and writing materials have been denied, except for occasional religious texts.

It would appear that the Indonesian Government is aware of the true state of prison conditions and has tried to camouflage them with misleading publicity statements. Since 1972, the Government has not allowed Indonesian and foreign journalists to visit prisons, apart from several conducted tours of the penal colony on Buru Island for Indonesian journalists, and one brief visit to the island by a Dutch journalist in 1976.

The reluctance of the Government to reveal to visiting missions and journalists the true state of political prisons is shown by its attempts to hinder the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross. Reporting on its 1977 visit to Indonesia, the International Committee of the Red Cross issued a terse and unusually critical public statement:

In submitting its report, the ICRC drew the attention of the authorities to the fact that its delegates’ findings could not be regarded as an indication of the real conditions of detention in Indonesia for two reasons: the limited number of places visited and the difficulties encountered during the visits. The ICRC will continue its visits to places of detention in Indonesia on the condition that these difficulties are overcome.

The Amnesty report also provides a detailed account of reprisals against prisoners who tried to speak to the visiting Red Cross delegates during a previous visit.

Although Indonesia ratified the International Convention on Forced Labor in 1950, it forces untried political prisoners to work under harsh conditions. The report of the Committee of Experts of the International Labor Office stated in 1976 that “the Indonesian detainees cannot be considered to have offered themselves voluntarily for the work in question, but are performing forced or compulsory labour within the meaning of the Convention. The Committee trusts that measures will be taken at an early date to put an end to this situation.” Again, in June 1977, the Report of the Committee of Experts to the International Labor Conference reiterated that “the detainees were required to perform forced or compulsory labour within the meaning of the Convention.” The Amnesty report provides examples of the use of untried prisoners to do forced labor in the penal colony on the island of Buru, in Nusakambangan, and elsewhere.

Advertisement

In 1975 and 1976, when the Indonesian Government announced the release of several thousand prisoners, Amnesty International requested information from the Indonesian Government identifying the prisoners released and the prisons in which they were held. The Indonesian Government has not responded to the request of Amnesty International for such information. Moreover, Amnesty International knows of others who have similarly approached the Indonesian Government for details identifying the people and the prisons in which they were held. No such information has been forthcoming.

The Indonesian Government also announced in December 1976 that it intended to release all untried political prisoners before the end of 1979, and that many of these prisoners were to be “released” in so-called “transmigration projects,” which will require them to be settled in remote colonies. For years the Indonesian Government has tried to justify the detention without trial of these prisoners on grounds of security, even though it admitted that it had no evidence against them for alleged involvement in the 1965 attempted coup. Now the Government’s position is that they can be released, but only according to a program involving both further delay and “transmigration.”

The Government’s announced intention to transfer many of the untried political prisoners to so-called “transmigration projects” is alarming. “Transmigration” of untried prisoners will mean the transportation of those prisoners to permanent penal colonies, such as the prison camps on Buru that now hold 14,000 untried political prisoners. Enforced transportation to permanent penal colonies should not be confused with the Government’s plans to encourage free Indonesian citizens to migrate to less densely populated regions of the Indonesian archipelago. Prisoners who have been forced to “transmigrate” to such penal settlements as Buru are compelled to undertake agricultural labor to produce all their own food and also food for the military garrison. No prisoner has been allowed to leave Buru and similar settlements to return to his home region. “Transmigration” to such settlements is a completely unacceptable alternative to immediate and unconditional release.

The Indonesian Government argues that both further delays in release and also the “transmigration” of prisoners are necessary because of the severe unemployment in certain parts of Indonesia. But the unemployment problem is not the fault of the prisoners. After so many years of arbitrary detention, the prisoners should be released and given the freedom to choose whether they wish to return to their home areas.

The Indonesian Government should be encouraged to release all untried prisoners and to cease its current policy of stigmatizing and harassing those who are released. To avoid uncertainty about the total numbers of prisoners held and the numbers of prisoners released, the Indonesian Government should permit competent international organizations to interview without hindrance political prisoners in all the prisons and prison camps throughout the Indonesian archipelago. Those who can influence the Indonesian Government should urgently seek the immediate and unconditional release of its untried political prisoners.

SONG OF THE PRISON

Prison-life’s a bird alike

Queue-up for maize-rice

Sleepless, your mind troubled

Powerless, your acts bridledPrison-life’s like self-torment

Entering thick, leaving slim

Forced labour and underfed

Still alive but nearly dead.

This song was composed by a prisoner in Tanggerang Prison, near Jakarta. It is now known to political prisoners in many Javanese prisons, and the prisoners continue to sing it despite attempts by the authorities to suppress it. (Indonesia: An Amnesty International Report, Amnesty International Publications, 1977.)

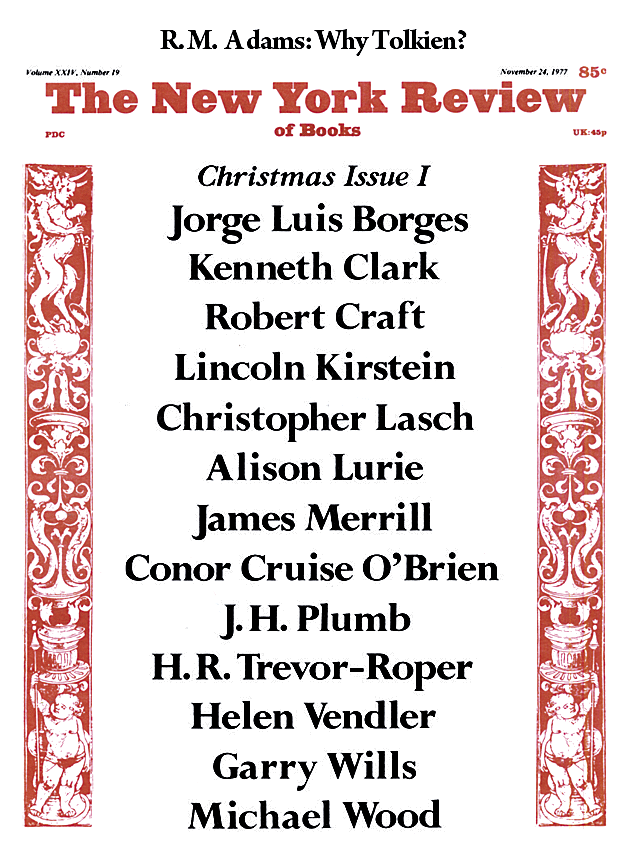

This Issue

November 24, 1977

-

*

Indonesia: An Amnesty International Report, Amnesty International Publications, 1977. Copies may be obtained by sending $3.50 plus $.25 postage and handling to AIUSA, 2112 Broadway, New York 10023. ↩