To the Editors:

As somebody who has recently been refused an interview for an openly advertised post in a state university explicitly on grounds of my color, I would be grateful for the opportunity to comment on Professor Dworkin’s lucid and interesting article (NYR, November 10).

Broadly, Professor Dworkin argues that those who find themselves excluded from education or employment because of the operation of affirmative action programs should console themselves with two thoughts: first, that all administrative actions and distinctions contain an element of arbitrariness; second, that, as long as they are not being rejected as members of a group habitually treated as inferior, they have no legitimate reason for complaint. Apart from that, Dworkin says, rather coldly, that, of course, we must have sympathy for Bakke, as for all who suffer incidentally from national policies, but that, after all, he had very little invested and was rather old to be starting a career (thirty-three). He also makes a curious analogy with the highway construction industry, to the effect that Bakke is the victim of technological progress.

In fact, one of the features of affirmative action programs is that they disproportionately hurt those who are fairly young and almost never touch those who have, as tenured professors, put their investments beyond risk. In my own experience, the employer (the State University of New York) made no attempt to indicate racial preference when advertising but refused to provide any information about the post (the chairmanship of its Africana Studies Program): I was merely told, five weeks later, that only blacks were to be interviewed and that my qualifications were, nevertheless, “very impressive.” As with Professor Dworkin, no attempt to explain or to sympathize. (All this, I might say, after fourteen years in the field and a post-graduate degree from an African university!)

Surely the most equitable implementation of affirmative action programs would be, at least in employment, to review all posts, senior and junior, in accordance with its principles. As matters stand, those who are excluded are dismissed as necessary casualties (including by Professor Dworkin who, elsewhere, brands as a “meaningless maxim” the notion that the end can justify the means) and are attacked as “racists” by the left and such bodies as the NAACP if they utter the mildest cheep of complaint.

I have every sympathy with the principles of affirmative action, but, as a foreigner, I would despair of its ever contributing to racial harmony, given the insensitivity of its radical and liberal protagonists toward those designated for sacrifice. They have much to say about and against casualties such as Alan Bakke; nothing, it seems, to say to them.

Martin Staniland

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

To the Editors:

In “Why Bakke Has No Case,” Dworkin defends the position that affirmative action quotas do not violate the rights of whites excluded from programs on grounds of race. An individual’s rights are violated, he contends, only when the tests employed to exclude him involve prejudice or contempt for a group of which that individual is a member. The affirmative action quotas express no such contempt for white males, but use race only to promote the laudable reduction of racial consciousness in America.

Let it be granted that at least part of the point of protecting individuals from exclusion from public benefits on the grounds of race alone is to protect groups, usually minorities, from public insult. Is it clear that this is the only point? Surely it is at least as much a concern that the value and dignity of individuals be protected, and this value and dignity is undercut by practices such as exclusion from public benefits by irrelevant tests such as race (or religion, or sex, or sexual preference). And just as surely, an individual’s worth and dignity can be threatened by such tests in individual cases, irrespective of their impact on groups.

What has encouraged the view that exclusion on irrelevant grounds violates a person’s rights only in those cases involving contempt or prejudice for a group? Perhaps it is that unfair exclusion is tolerated in case no readily identifiable group is involved. But this does not establish the point that only the protection of groups is at issue. Historically, individuals have been excluded unjustifiably, on the basis of race, religion, or sex, and it is natural that concern for the worth of individuals should emerge in the form of the right not to be excluded on these grounds. The law cannot proscribe every form of injustice of this sort, but it can identify the most common forms and prohibit them. Here, as often, the law does what it can. If this is correct, then Bakke does have a right to be judged on his own merits even though, should he not be so judged, he will not suffer from contempt or prejudice. (I pass over without comment Dworkin’s desperate claim that, in being excluded on grounds of race, Bakke is being judged on his merits [pp. 14-15].)

Advertisement

If Bakke’s rights are being denied by affirmative action, it is crucial to examine the program. What is its point, and what are its prospects of success? Dworkin denies that blacks and other minorities are entitled to preferential treatment (though on this he is fuzzy—by page 15 he has slipped into describing the goal of affirmative action as an “attack on present and certain injustice”), so the only issue can be that of individual rights balanced against the probable social benefits of affirmative action.

Here I cannot share even the guarded optimism Dworkin allows himself. The program will generate a black professional class which will better serve blacks, it is claimed. But what guarantee have we that a black professional class will willingly foresake more lucrative practices, if they can get them, to work in black areas? (One must beware of succumbing to what Bertrand Russell once called the myth of the moral superiority of the oppressed.) It is suggested that black professionals are needed to provide “role models” for black children. But it is difficult to assess how to balance this consideration against the plain fact that quotas generate resentment among those whose rights, as I have argued, must be overridden; and also difficult to balance the advantage against the self-doubts that quotas must arouse in those who benefit from them.

These problems might be set aside if we had assurance that quotas are only temporary. Dworkin offers such assurance, but I can see no reason to believe that reasons for instituting quotas will not be reasons for continuing them, if it should appear likely that discontinuing them would erode the gains blacks make under them. Since the under-representation of blacks in the professions is caused in the main by conditions that quotas themselves will do nothing to correct, such as poverty and a history of oppression, there seems no reason to think that quotas once introduced will not be required for as long as these conditions prevail. And indeed, it would be cruel to provide blacks with “role models” in the professions, thus raising their expectations as well as, perhaps, their self-assurance, and then to remove the conditions on which realizing these expectations depend.

John Robertson

Syracuse University

Syracuse, New York

To the Editors:

…Dworkin is correct when he asserts that merit is difficult to define, and that individuals are rarely judged as such in any pure philosophical sense: we are always categorizing and grouping in the course of making judgments. Yet this does not mean that all characteristics put forth as possible components of “merit” or all treatments of an individual as a member of a group, have equal legal or moral claims for all cases. Historical experience and empirical common sense, operating through the processes of legislation and judicial interpretation, have established a consensus on a number of theoretical principles denoting the best in the Western liberal-democratic tradition. One such principle is that except for the rarest of rarest exceptions (males cannot be wetnurses), ascribed traits such as race, religion, and one hopes sex, may play no role in the public life (housing, education, employment) of citizens. A historic toll of blood and oppression, as well as the understanding that skin color bears no intrinsic relationship to the ability to hit a baseball or interpret an electrocardiogram, have shaped this consensus. Other traits, such as age, are complex and need reflection; still others such as height, or strength, enter our notions of merit without violating our sense of justice or fairness, in limited cases (basketball players, jockeys). There is little reason, other than capricious relativism, why remaining ambiguities in these latter cases need undermine the hard-won recognition of the illegality of the former.

Morton Weinfeld

McGill University

Montreal, Canada

To the Editors:

In your issue of November 10, Ronald Dworkin announced that “Bakke has no case.” Constitutional lawyers are deeply divided on the issue, and many militant Blacks are so fearful of a decision in favor of Bakke that a major effort was launched to persuade the Court to deny certiorari, i.e., to let the California decision stand without passing on the merits. Bakke may indeed lose; the Court may set its imprimatur on racial handicapping. If so, it will not be on Dworkin’s grounds.

Perhaps Dworkin’s failure to see any case for Bakke stems from his misperception of the issue. He starts his argument by declaring that Bakke “applied for one of the remaining eighty-four places”—i.e., those left over after sixteen places had been preempted for non-Whites. Bakke did no such thing; he applied for one of the full hundred available slots, not supposing that he could be barred by a state institution from any available opportunities solely on the ground of color.

Advertisement

Much of Dworkin’s essay is directed at showing that affirmative action is necessary in order to make opportunities equally available to all groups. That is not the issue. There is virtually unanimous agreement on the legality and desirability of affirmative action. The only issue is as to one rare and radical form of affirmative action: a quota from which Whites are excluded. The California Supreme Court in deciding for Bakke outlawed only that; and it outlawed that only because other effective forms of affirmative action are available.

Among forms of affirmative action which the California decision permits and encourages are:

1) actively seeking Black applicants.

2) supplementary training to qualify Black applicants affected by surviving racial disadvantages in schooling and employment.

3) preferring Blacks over higher ranking applicants to the extent that a poly-racial setting improves medical training of all students.

4) preferring Blacks over higher ranking applicants to the extent that Black applicants commit themselves to serve underprivileged Black communities more frequently than Whites.

The California decision even permits preferential Black admissions on the highly dubious basis that it is a function of state education to bring about an allocation of “leadership” positions in society on an ethnically proportioned basis.

Although Bakke had not proved that he would have been admitted to medical school if the sixteen places reserved for Blacks had been available to him (i.e., there might have been more than sixteen Whites higher on the admissions list than Bakke), the California Court recognized that he had been wronged by the reservation of sixteen places for Blacks. He would have been admitted if he were Black, since his qualifying scores were much higher than Blacks who were admitted. His chances of being admitted from the White “queue” were reduced by the reduction in the total of White admissions. Finally, he was excluded from the “Black” queue without any comparison with Black admittees, even by the criteria which led to the creation of a separate Black queue. A White would be barred from the Black queue even if he was married to a Black, had adopted Black children, was a civil rights activist, was a student of Black history and culture, was a veteran of VISTA in Africa, and gave bond to practice in a Black community. Conversely, a Black would have been admitted although he was ignorant of and hostile to uniquely Black culture, fully integrated into the White community, and dominated by bourgeois “White” aspirations.

It is clear that the California Court did not mandate “racially neutral means” of selection, as Dworkin erroneously states. The United States Supreme Court will not be mandating “racially neutral means” because that’s not at issue in the case, and because the Court has many times sustained racially sensitive governmental action to improve the lot of minorities.

The heart of Dworkin’s argument is that Blacks will get into professional schools only if quotas are set aside for them. This contradicts experience at many schools where non-quota systems are working. The Dworkin argument also constitutes the ultimate White insult and condescension: that Blacks cannot get in by any conceivable rational set of admissions criteria, however sensitive to racial and social factors. Skin color is the only test by which they can prevail. That devastating put-down is rejected by many Blacks, including a colleague of mine who has declared himself against “special admissions” as stigmatizing. What is wanted is a broader view of the way qualifications should be measured. Aptitude tests and college grades are useful selection aides, but they are crude guides at best. There are dimensions of personality including commitment, stability, human sympathy, and unique social point of view that should and do enter into all student admissions programs. The Dworkin view that only the skin-test will respond to such factors is ridiculous.

Dworkin’s argument that the unfortunate impact of racial handicapping on Bakke should not be allowed to stand in the way of an “experiment” on the way to the distant goal of a prejudice-free society betrays an insensitivity to the significance of constitutional litigation. The Supreme Court is not asked to weigh its sympathy for Bakke against the desirability of racial justice. Bakke is simply the accidental protagonist in a critical controversy over the shape of our democracy. The issue is whether we as a nation shall move from a policy against discrimination to a “race policy” explicitly addressed to assuring ethnic proportional representation not only in the schools, but in the professions, in Congress, and perhaps in the White House, where racial and religious changeovers on the model of the old Lebanese government would be the order of the day.

I write as one whose whole career has been identified with promotion of civil liberties, especially of Blacks, opposition to the death penalty, restraint on police abuses, and with effective affirmative action. I chaired the Faculty Committee which first succeeded in recruiting Black professors. I cringe at the notion that my Black colleagues should be regarded as “inferior” scholars or teachers, whom we had to accept to carry out a social or political policy.

Louis B. Schwartz

Benjamin Franklin University

Professor of Law

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

To the Editors:

Undoubtedly Ronald Dworkin will want to correct what seems like a clear error when he writes, “Only the most naïve theories of statutory construction could argue that such a result [forbidding action such as that taken by the University of California, Davis Medical School] is required by…the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

The Supreme Court, as has been widely reported, has requested briefs from the parties in the Bakke case on the bearing of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act on the case, and that title contains the following language:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground of his race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Of course the Davis Medical School, as is true of all medical schools, receives Federal financial assistance.

Nathan Glazer

New York, New York

To the Editors:

…What can we expect from affirmative action programs? Are they the necessary tool in the reversal of this outright misery? Why the concentration of well-intentioned energy on the Bakke case? One is reminded of the focus on sickle-cell anemia of a few years ago, stopped only when blacks themselves made the case that such focus was misplaced. The small number of black doctors and other black professionals that would come into being under affirmative action programs—but not otherwise—will not make much difference amidst the comparatively large number of unskilled and unemployed. Nor does it make good sense, moral or otherwise, to stop here with the case of blacks. The claims of others who have been excluded, women and blue collar workers (whose children, for whatever reason, tend to repeat the cycle of their parents—employment during boom, anxiety over cutbacks and actual unemployment during “recession”) for example, will not be satisfied under affirmative action programs of the sort Dworkin supports.

The reply to this might be that affirmative action programs aren’t meant to erase such large scale inequities, but only to supply a comparatively small, but noticeable, number of professionals (“noticeable” on the assumption that most of them stay close to the impoverished areas). But then again, why the crucial importance of the Bakke case? Those of us who want to effect change have finite resources to do so. Why spend so much of these resources on this? Hopefully not in the vain hope that the other problems are being taken care of. Pick and shovel make-work “full employment” schemes such as Humphrey-Hawkins are no more than New Deal type bandaids. By now the lesson must have sunk home that we need far more ambitious projects if we are seriously seeking social progress….

An overall attack on the problems besetting us demands changes in our financial structures. Existing debt ought to put aside for the while, in order that capital be freed for development. Such a proposal does not find favor in those powerful circles which are more interested in immediate debt collection. It is therefore not likely accidental that we find the Rockefeller Foundation and similar groups all too eager to fund “zero growth,” “small is beautiful,” “local control,” and similar anti-progress proposals. Various well-meaning people such as Dworkin (if not Dworkin himself) indeed have a friend at Chase Manhatten.

Within a program of genuine all out development, schemes for improving the skill levels of those previously excluded make sense. Without such a program we are fighting over the crumbs in a collapsing house. In the present circumstances, I do not care whether or not Bakke has a case.

Asher Seidel

Department of Philosophy

Miami University

Oxford, Ohio

Ronald Dworkin replies:

The many letters to the NYR, only a few of which could be published, confirm that Bakke’s supporters are largely people of very good will who hate racial prejudice but who are deeply worried about either the fairness or the wisdom of affirmative action. Mr. Staniland reminds us that those who are excluded because of affirmative action are often bitter, and resent the excuses offered to them, particularly by those whose careers are already secure. I did not mean to seem cold. I did say that someone excluded simply because his college grades or test scores were low deserves as much sympathy, but I did not mean that to seem cold either.

I agree with Staniland’s observation that universities and other institutions which depart from conventional standards have a responsibility to consider carefully whether their new standards are well suited to their own enterprise, so that they do not choose them simply out of fashion. While a medical or law school might rationally favor minority candidates for admission, it does not follow that a university ought to limit its consideration of candidates for an academic post to a single race. The purposes of an academic appointment are different, and though there may well be reasons to use racially conscious tests there as well, these reasons will be different, and the reasons opposing racial preference may well be stronger. It is impossible to judge Staniland’s specific complaint on so few facts, but it may well be that it was not reasonable, given the relatively small number of candidates, to deny him an interview in which he might have demonstrated that his special African experience made him more suitable than any black candidate.

I also agree with Professor Robertson that the requirement of the Constitution, that people be treated as equals, protects individuals rather than groups. Prejudice in official decisions is wrong, not because some group is made worse off as a whole, but because it treats an individual with contempt. Someone is also treated with contempt, as Robertson says, if he is denied an advantage for irrelevant reasons. I argued that race is not irrelevant when an important social goal is to reduce racial consciousness. Robertson says that this argument is “desperate” and best passed over in silence. But what is relevant, in deciding whom to train to become a doctor, depends upon fact, not convention. If a certain form of treatment requiring physically strong doctors became popular, then physical strength, not now relevant, would become so. It is regrettable that the facts now make race relevant, but they do.

Nor do I find much appeal in Professor Weinfeld’s suggestion that we should trust “historical experience and empirical common sense” to produce a “consensus” on what qualities are relevant for admission to medical school. If a consensus has now formed that “skin color bears no intrinsic relationship to the ability to hit a baseball,” that is because Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers challenged an earlier and contrary consensus. No one who advocates affirmative action in medical schools believes that skin color bears an intrinsic relationship (whatever that is) to the ability to read an electrocardiogram. They believe that black skin may for the moment improve a doctor’s ability to provide medical services and provide an example of success to a community much in need of both. That judgment is not a piece of “capricious relativism” but an empirical hypothesis. It may be wrong, but that does not depend upon whether it now commands a consensus.

Robertson believes it is wrong, because he thinks it assumes that black doctors are more altruistic than white doctors, and more likely to accept lower fees to work in ghettos. Of course no one thinks that all black doctors will prefer Harlem to Park Avenue, and there are arguments for affirmative action that do not assume that any will. I do myself think, on limited experience, that blacks who graduate from professional schools are as a group more likely to feel responsibility to help less fortunate blacks than are whites, and the careers of those who graduated from the Davis task force program support my judgment. In any case there are reasons other than altruism that make a black doctor more likely to have a black practice than a white doctor is. Perhaps black doctors will some day be so well accepted by middle-class white patients that this generalization will fail, and affirmative action programs will for that reason no longer be effective. But in that case they may no longer be necessary either.

Professor Schwartz believes that I misunderstand the legal position. I said that the California Supreme Court opinion in Bakke condemned all racially explicit admissions programs. I meant all programs that take race into account as an explicit criterion of admission, whether as one factor to be balanced against others in individual cases, or through actual minority quotas. Schwartz believes, on the contrary, that the California Court prohibited only one “rare and radical form of affirmative action,” which is the use of quotas, and he finds “virtually unanimous agreement on the legality and desirability” of other forms of affirmative action.

If he uses “affirmative action” to include racially explicit criteria, then he is wrong in supposing unanimous agreement, as the other letters make clear. He also misreads the California opinion. The United States government’s brief to the Supreme Court, amicus curiae, did draw a distinction (which I believe is unsound) between quotas and other forms of racially explicit affirmative action. But the California Court made no such distinction. It conceded, arguendo, that medical schools may pursue racially explicit goals, like the goal of providing more doctors for black communities or enriching the medical school environment through racial diversity. Perhaps Schwartz assumes that if the Court permits racially explicit goals it must permit racially explicit admissions criteria as means to those goals. But in fact the Court expressly denied that permission.1 The means it suggested were in fact these:

Disadvantaged applicants of all races must be eligible for sympathetic consideration…. The University might increase minority enrollment by instituting aggressive programs to identify, recruit and provide remedial schooling for disadvantaged students of all races…to increase the number of places available in medical schools…. None of the foregoing measures can be related to race, but they will provide for consideration and assistance to individual applicants who have suffered previous disabilities, regardless of their surnames or color…. Whether these measures, taken together, will result in the enrollment of precisely the same number of minority students as under the current special admissions program, no one can determine. [Emphasis added.]

In every part of its opinion the California Court made plain that its target was not simply quotas, but the assumption, stated in the dissenting opinion, “that minority status in and of itself constitutes a substantive qualification for medical study.” The Court’s condemnation of racially explicit tests was comprehensive. The spirit of the opinion would, in fact, condemn Schwartz’s own committee “which first succeeded in recruiting Black professors” if, as I suspect, that committee set out to find highly qualified black faculty members, rather than “disadvantaged” faculty members “of all races.”

Schwartz’s misunderstanding of the California opinion contributes to his misunderstanding of my own position.2 “The heart of Dworkin’s argument,” he says, “is that Blacks will get into professional schools only if quotas are set aside for them.” That is doubly misleading. I said that I was considering the need for racially explicit admissions programs in general, not simply those that use, as Davis did, a quota. (I suggested, indeed, that the latter might be too crude as a matter of wise administrative practice, even though they are not, for that reason, unconstitutional.) I did say that there is very substantial evidence that only racially explicit programs of some sort offer much promise of substantially increasing the number of blacks in professional schools. If it is this opinion that Schwartz finds ridiculous, rather than the opinion that quotas are necessary, then he presumably rejects the full and documented report of the Carnegie Council on Higher Education, on which I relied. He might have said why.

I also said that claims about the long-term effects of affirmative action are controversial, and that it cannot even be proved, beyond reasonable doubt, that they will do more good than harm in the long run. (I specifically mentioned, as one genuine cost of such programs, a fact Schwartz emphasizes, which is that some blacks, like his colleague, resent them.) The “heart” of my argument, therefore, is not a claim about the beneficial effects of the programs, but rather a very different claim. I argue that in these circumstances, when there are good if not conclusive reasons to think the programs will help to attack an otherwise intractable social problem, people in Bakke’s position have no right to prevent those who are persuaded by these reasons from acting on their own judgment. I do not mean, of course, that an institution is justified in invading individual rights in pursuit of a goal it takes to be worthwhile. My point is rather that people in the position of Bakke do not have, in law or in morality, the rights that are claimed for them. I provided arguments to that point, but Schwartz says nothing to contest them.

He does offer one opinion, however, that may explain why he does not try to meet my central point. He says that I am “insensitive” because I do not understand that “Bakke is simply the accidental protagonist in a critical controversy over the shape of our democracy. The issue is whether we as a nation shall move from a policy against discrimination to a ‘race policy’ explicitly addressed” to proportional representation of all races in every profession. The second sentence is simply the familiar straw man. Affirmative action does not presuppose the desirability of what I called a balkanized society, nor is there any real danger that it will in fact produce one. The first sentence is more troublesome.

It is not the business of the Supreme Court, or of any other court, to decide “the shape of our democracy” except insofar as one shape rather than another is required to protect the rights of individuals. The qualification is important: the last two decades of constitutional litigation show how far the programs of governments and private institutions may have to be adjusted in order to protect the rights the Court thinks individuals have. But even those who defend the most revolutionary decisions of the Warren Court do not think that the Court should remake society except for that purpose. Bakke is an “accidental protagonist” in the sense that it is an accident that he, rather than someone else in his position, is the plaintiff in this case. But the question of what rights he has must be, as his lawyer insisted, decisive of this crucially important law suit.

Professor Glazer raises a more technical point. I said that only a naïve theory of statutory construction could argue that the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by itself requires a decision in favor of Bakke, so as to make any consideration of the issues of political morality I discussed irrelevant. The Supreme Court subsequently asked for further briefs on the issue of whether Title VI of the Act does apply. Glazer thinks that the Court’s request shows that I made a “clear mistake.” But if the bare language of the statue is indeed decisive, the Court would hardly have required further briefs about its correct construction.

The naïve theory I had in mind holds that the provisions Glazer quotes admit of only one meaning. In fact the meanings of the key terms vary with context. It would be perfectly natural to say, for example, that since the great majority of places were not reserved for minorities, Bakke was not excluded from the program or denied its benefits on grounds of race alone. And that since “discrimination” supposes prejudice, he was not the victim of discrimination. Even the phrase “on grounds of race” in most contexts suggests prejudice. It seems natural to say that a black actor has been excluded from a social club on racial grounds, but odd to say that he is not permitted to play Hamlet, in a conventional production, on grounds of race. It seems more accurate, in the latter case, to say that he cannot play Hamlet because of his color; unless, of course, we mean to suggest that racial prejudice lies behind the assumption that black actors should not be cast as Hamlet, in which case it would seem accurate to say that black actors are barred from the part on racial grounds. Of course, we can imagine contexts in which the phrase “on grounds of race” would not carry a suggestion of prejudice. But the phrase does not have a plain meaning, independent of context, which unambiguously includes affirmative action programs.

We must therefore look to the legislative history of Title VI. That history supports the view that the clause was intended merely to enforce rights already protected by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. That was, in fact, the view that Bakke’s own lawyers argued to the California courts. Senator Hubert Humphrey, the floor manager of the bill, told the Senate that “The purpose of Title VI is to make sure that the funds of the United States are not used to support racial discrimination…. Thus, Title VI is simply designed to insure that Federal funds are spent in accordance with the Constitution and the moral sense of the nation” (110 Cong. Rec. 6544). If so, then since the correct construction of the Constitution turns on issues of political morality, the correct construction of Title VI turns on the same issues.3

It is of interest, moreover, that the regulations issued by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare under Title VI explicitly recognize that a recipient of federal funds, even one not itself guilty of past discrimination, “may properly give special consideration to race, color, or national origin to make the benefits of its program more widely available to such groups.” That would, of course, be illegal under the naïve interpretation; indeed it would be illegal even if the recipient had been guilty of discrimination in the past. The naïve interpretation would also prohibit programs no one thinks illegal, some of which have been approved by the Supreme Court, like busing programs for schoolchildren within districts guilty of past discrimination. I do not think that there is a defensible interpretation of Title VI that aids Bakke. The Supreme Court may disagree, but if so it will not be because it accepts the naïve interpretation that forecloses the issues I discussed. It will be in consequence of the Court’s own judgment on these issues.

Professor Seidel does not worry, as Schwartz does, that affirmative action will radically change American society. Seidel’s objection is rather that it will make no significant change at all, and he therefore believes that the energy spent in devising, administering, and defending these programs should instead be spent on more fundamental social and economic reforms. I do not understand why concern for the one excludes concern for the other. Racial consciousness is an important cause of racial inequality, and racial consciousness will be diminished when blacks and whites no longer feel, as so many now do, that the best and most important jobs are reserved for the latter. Presumably Seidel thinks that affirmative action programs are bribes paid by liberals to blacks to keep them from pressing, along with the rest of the poor, for more dramatic changes. Even if this is so, however, it seems more likely that the programs will do some good than that they will prevent a revolution that would otherwise take place. If so, then the indifference of radicals would be perverse.

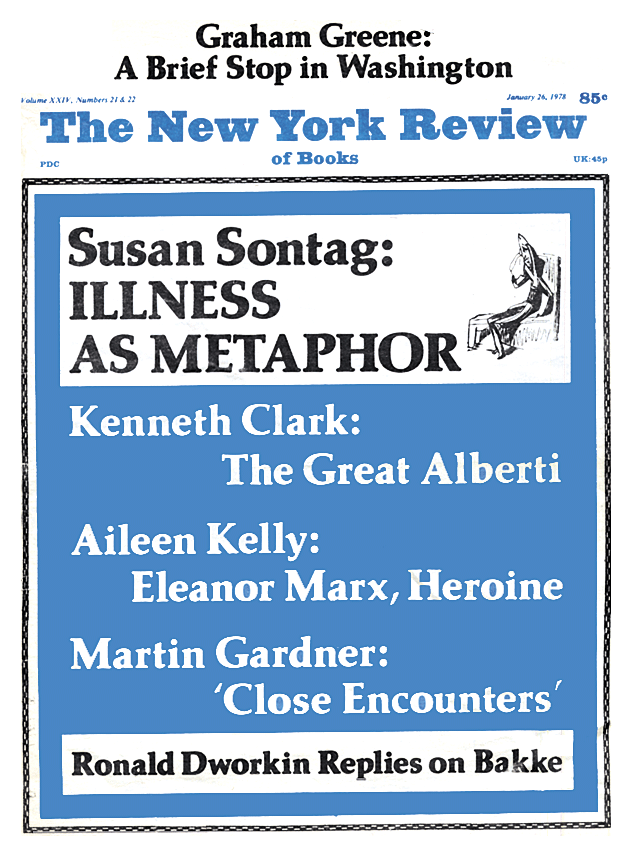

This Issue

January 26, 1978

-

1

In my article I suggested that the recommendation that universities pursue racially explicit goals through racially neutral means is either hypocritical or unrealistic. ↩

-

2

Some of his mistakes are unimportant. He quibbles, for example, with my statement that Bakke applied for one of the eighty-four ordinary places rather than one of the sixteen “minority” places. In fact the admissions forms described the program, and gave Bakke the opportunity to apply for the minority program, which he declined to do. Of course, his failure to apply for a minority position did not waive his right to protest the entire program. ↩

-

3

This theory of constitutional construction was explained in my article “The Jurisprudence of Richard Nixon” (NYR, May 4, 1972; reprinted in Taking Rights Seriously, Harvard University Press, 1977). ↩