The Hungarian Sinologist Etienne Balazs once remarked that in imperial China, “History was written by officials for officials.”1 The dynastic chronicles were monopolized by emperors and their ministers, by statesmen and literati. The common folk hardly appeared at all in these records, other than as an abstraction: “the peasants,” “the hundred surnames,” “the black-haired masses.” And even if they could have recognized themselves as individuals on the histories’ pages, most commoners would not have been able to understand the classical language in which the accounts were written. History was thus expressed and dominated by the imperial presence and its Confucian mandarinate. The perspective was set by the Forbidden City, where the emperor looked down upon his subjects beneath him. Rural China and its inhabitants, the poor and nameless, existed somewhere in the lower depths, under the gentry and bureaucrats who connected the ruler with the ruled.

This top-heavy image of a brooding imperial presence has by now become a cliche, but it is one not easily avoided. It is very difficult, for instance, even to see the real person of the emperor behind his own facade of rule. This was partly because the emperor was his own mythmaker. The K’ang-hsi Emperor (reigned 1661-1722), who completed the Manchu conquest of China and consolidated the rule of his Ch’ing dynasty (1644-1911), not only altered the historical records to minimize the barbarian characteristics of his ancestors; he also carefully cultivated the manners of a Confucian sage-ruler, often appearing in a series of carefully selected poses before his subjects. All men play roles, but the Chinese emperor more than most rulers possessed a repertoire of stereotypes to draw upon, and consequently seemed to contemporaries more a persona than a person.

One of the first scholars to expose the individual ruler behind the imperial presence was Jonathan Spence, professor of Chinese history at Yale University. Spence’s first book2 was an unusually intimate study of the relationship between the K’ang-hsi Emperor and his personal bondservant, Ts’ao Yin, whose own family was probably the inspiration for China’s best-known novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber (Hung-loumeng). Ts’ao Yin, who supervised the Imperial Household’s monopolies in the wealthy cities of the Yangtze delta, communicated with K’ang-hsi by secret memorials. Spence was able to use these documents from Chinese archives to draw a robust portrait of the Ch’ing ruler. Later, in a second work on K’ang-hsi,3 Spence did even more to reveal the person beneath the dragon robes of state. Culling singular comments by K’ang-hsi from a selection of public edicts, testamentary rescripts, and private letters, Spence boldly combined these individual statements into collective discourses that reflected the emperor’s own thoughts about statecraft and moral philosophy, about riding to the hunt and commanding troops in battle, and about raising children and enduring old age. This technique of composing a single set of verbal reflections from snatches of writings scattered here and there was been criticized by scholars, but no other historian has ever allowed us to experience the intensity of a Chinese monarch’s personality with as much flair as Spence has.

Yet this was still history at the top. Though Ts’ao Yin was nominally an imperial bondservant, the master he served was ruler of all China. That alone made Ts’ao Yin wealthy and powerful beyond most men’s dreams. And though he and his ruler left Peking to travel elsewhere inside the Great Wall, it was usually the highly cultured Yangtze delta that they visited. There, in the alluring cities of the south, they stayed in the homes of wealthy salt merchants or in palaces specially built for them by the official gentry. The scale was smaller, but the extravagance was no less grand than that of the Forbidden City they had left behind. K’ang-hsi and Ts’ao Yin thus remained within a zone of metropolitan civilization that was superimposed upon the map of China in the shape of an hourglass, with Peking and its environs in the north connected by the Grand Canal to glamorous Soochow in the south. As the art historian Nelson Wu has described China during that period:

The northern end, having as its center the national capital of Peking, was the political arena for all, where prizes in fame, riches and posthumous titles were given as frequently as severe punishment was meted out…. Connected to this political nerve center by a narrow passageway roughly paralleling the Grand Canal was the cultured land of the lower Yangtze valley, with such illustrious towns as Soochow, Ch’angchow, Sungkiang, Kashing, Hangchow and the [former] southern capital of Nanking.4

Outside that zone existed another China where life during the seventeenth century, when rebel armies swept the land, was much harsher. K’ang-hsi certainly knew this darker territory, but he generally preferred to abide at one or the other end of the zone of light, which is also where students of Chinese history have mostly dwelt.

Advertisement

In his latest work, The Death of Woman Wang, Jonathan Spence moves down from the top of Chinese urban society into its rural lower depths, from the palaces of the K’ang-hsi Emperor to the poverty-stricken villages of western Shantung. As he tells us in his preface:

This book is set in a small corner of northeastern China during the seventeenth century. The precise location is a county called T’anch’eng, in the province of Shantung, and most of the action takes place there in the years between 1668 and 1672. Within that time and place, the focus is on those who lived below the level of the educated elite: farmers, farm workers, and their wives, who had no bureaucratic connections to help them in times of trouble and no strong lineage organizations to fall back on.

T’an-ch’eng lay along the corridor that connected the wealthy provinces of the south with the urban capital in the north. It was bleak, inhospitable terrain, and examination candidates on their way to Peking to take the metropolitan examinations passed through this wretched hill country with trepidation, praying that their carts would not bog down on the post road and leave them vulnerable to highway robbers sweeping down from fortified villages. Entire districts during this period were noted for professional banditry.

Like our Appalachia, it was one of the poorest regions of China, and in the seventeenth century constantly beset by turmoil and disaster, both natural and human. In 1622, White Lotus sectarians had rebelled there; in the 1630s, famines swept the western part of Shantung; in 1640, locusts appeared; in 1641, bandits invaded the district capital of T’an-ch’eng; and in 1643, the Manchus raided the province, raping women, seizing property and livestock, and enslaving prisoners of war to take back beyond the Great Wall to till their estates.

In 1644, the Manchus came to stay for good, occupying Peking and announcing the foundation of the Ch’ing dynasty; and the local gentry of Shantung quickly came to terms with this new ruling house, which reigned in the name of Confucian principles and which sent military forces to patrol the fitful countryside around T’an-ch’eng. From the vantage point of Peking, this part of China required careful control. Always prone to violence and rebellion, its momentarily settled rural society only seemed on the surface to be stable. Underneath the apparent stability, the new rulers felt, lay potential chaos.

Spence’s study penetrates that surface, and tries to convey to us the misery of lower-class life in seventeenth-century China through a series of crises that culminate symbolically in the death of a woman known only by her father’s surname of Wang: an adulteress, strangled to death by her husband in the year 1672.

The murder of woman Wang takes up only a few pages in this extraordinary book. It forms the occasion, so to speak, for Spence to study the world that surrounded the victim.

When I came across her story by chance in a library several years ago, she led me to T’an-ch’eng and into the sorrows of its history, into my first encounter with a peripheral county that had lost out in all the observable distributions of wealth, influence, and power.

Thus, it is the local history of the district of T’an-ch’eng that really forms the major portion of this work, and it is from the county gazetteer and the memoirs of a magistrate5 who served there in the 1670s that Spence gets most of his information.

The Death of Woman Wang opens with a dramatic description of the powerful earthquake that struck T’an-ch’eng in 1668 with much the same force as the temblor that devastated T’ang-shan in 1976 and reportedly killed 700,000 people.

The earthquake struck T’an-ch’eng on July 25, 1668. It was evening, the moon just rising. There was no warning, save for a frightening roar that seemed to come from somewhere to the northwest. The buildings in the city began to shake and the trees took up a rhythmical swaying, tossing ever more wildly back and forth until their tips almost touched the ground. Then came one sharp violent jolt that brought down stretches of the city walls and battlements, officials’ yamens, temples, and thousands of private homes.

This scene of utter devastation, of mass death, frames the local gazetteer’s catalogue of wretchedness before and after the tremor struck: famine and attendant cannibalism, broken families and sexual promiscuity, bandits and violent death, military rapine and plunder. As Magistrate Huang Liu-hung found when he began his service in the country in 1670:

T’an-ch’eng is only a tiny area, and it has long been destitute and ravaged. For thirty years now fields have lain under flood water or weeds; we still cannot bear to speak of all the devastation. On top of this came the famine of 1665; and after the earthquake of 1668 not a single ear of grain was harvested, over half the people were dying of starvation, their homes were all destroyed and ten thousand men and women were crushed to death in the ruins.

“By 1668,” writes Spence, “the people of T’an-ch’eng had been suffering for fifty years.”

Advertisement

If Spence had relied solely on the district gazetteer and on Magistrate Huang’s memoirs for material, his account of the horrors of existence in T’an-ch’eng might have become a dreary and lifeless enumeration of collective miseries. But in addition to highlighting his social portraits with information from a wide range of primary and secondary sources in Chinese, Japanese, and Western languages, Spence enlivens the official reports with material from China’s greatest short story writer, P’u Sung-ling (1640-1715). P’u, who was born in the town of Tzu-ch’uan 140 miles to the north, was in Shantung at the same time that the earthquake struck T’an-ch’eng. Spence deftly uses that coincidence to draw the famous author of Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (Liao-chai chih-i) into his own account:

P’u Sung-ling heard the roar of the 1668 earthquake moving up from the direction of T’an-ch’eng as he was drinking wine with his cousin, by the light of a lamp:

“The table began to rock and the wine cups pitched over; we could hear the sounds of the roof beams and the pillars as they began to snap. The color drained from our faces as we looked at each other. After a few moments we realized it was an earthquake and rushed out of the house. We saw the buildings and homes collapse and, as it were, rise up again, heard the sounds of the walls crashing down, the screams of men and women, a blurred roar as if a caldron were coming to the boil.”

Although P’u Sung-ling’s stories are formally classified as fiction, they closely reflect his own experiences in Shantung then and later in his life: and, as used by Spence, they lend zest and drama to the more formal and stereotyped accounts of the local gazetteer. Not that Spence neglects conventional local history: his study includes reports on taxation, military organization, judicial practices, and official administration. But by judiciously supplementing this institutional analysis with passages from P’u Sung-ling’s sometimes biting, sometimes haunting accounts of contemporary Chinese society, he breathes life into his social history of the common folk of T’an-ch’eng.

Some of the material from P’u Sung-ling verges on fantasy: he tells of a “world of ghosts and nightmares” peopled with female shamans who foretell the future, with fox spirits who change into beautiful women to seduce the unwary and lead them to their doom, and with Taoist magicians who learn how to summon the Judges of the Underworld to punish the wicked on earth. But none of these stories is far removed from popular beliefs at the time, and Spence frequently relates the narratives to peasant religion and to the very real magicians who often instigated the local rebellions that so alarmed imperial authorities.

Much closer connections are drawn between P’u’s accounts of family feuds between brawling liegemen (chia-ting) or of corrupt gentry embezzling tax receipts, and the personal experiences of Magistrate Huang who frequently wrote about the difficulty of enforcing law and order in the district. Spence also shows the connection between the idealized biographies of virtuous woman (liehnü) in the T’an-ch’eng county gazetteer and P’u’s sardonic stories about widows who refused to remarry, as well as between horrifying accounts in the local history of women assaulted by soldiers and P’u’s terse tale of the woman Chang, who lured two would-be rapists into a pit and burned them to death.

One of the most prominent motifs in The Death of Woman Wang is the continual dilemma of women caught between ideal Confucian norms of behavior and the harsh demands of the rural life that made a mockery of those values. I can think of hardly any other book about traditional China that reveals their plight so movingly, or that so tragically depicts the hopelessness of ravished young women or of beaten wives. This is because Spence’s imaginative powers, his gift for empathy, are strong enough “to conjure up from the past the lives of the poor and forgotten.” Nowhere is this more evident than in the tale of woman Wang herself.

Virtually nothing is known of “the woman called Wang who married a man called Jen” apart from Magistrate Huang’s report of the circumstances surrounding her death in the market town of Kuei-ch’ang, just outside the county seat of T’an-ch’eng. In 1671, according to the report, the woman Wang left her husband Jen, a farm worker, to run away with a nameless lover. The adulterers’ sojourn in Shantung’s “fugitive subculture” of bullying innkeepers, wandering magicians, corrupt policemen, and rapacious ferrymen was brief. Ultimately abandoned by her lover on the highway and liable to serious punishment from the authorities for having left her husband, the woman Wang (whose feet were bound) had no recourse but to hobble back to her native Kuei-ch’ang and seek refuge in the Taoist temple there. Sheltered by a priest, she was eventually discovered by her husband who, while at first enraged, soon took her back to their one-room hovel.

The two of them lived together again, in their house outside Kuei-ch’ang market, through the last months of 1671 and into January 1672. They would have been cold, for the mean temperature in Shantung during January was in the twenties, and the houses of the poor were frail: the walls were of beaten earth, mud bricks, or kaoliang stalks; the few wooden supports were unshaped branches, often thin and crooked; roofs were thatched thinly with straw and reeds and were not true proof against either wind or rain. If there was fuel available, it was used primarily for cooking, and the warmth from the cooking fire was fed under the raised brick sleeping platform through a system of flues; this sleeping platform was covered with a layer of straw. In Jen’s house it was here that he placed the new mat he bought for woman Wang’s return.6

The new bed mat may have temporarily patched up the relationship between them; but, as neighbors later reported to the magistrate, the couple soon quarreled, and it was beside that same mat that Jen ominously waited for his wife to fall asleep after their final argument on a cold January night in 1672.

At this point in his account, Professor Spence becomes, for me at least, momentarily maladroit. As the woman Wang falls asleep, the author has her dream for us a reverie. The sequence of images in this italicized fantasy is an ingenious collage of passages that occur here and there in the writings of P’u’ Sung-ling. A vision of paradise, the reverie is disconcertingly placed in the middle of the carefully reconstructed history of that night’s events by Spence, who apparently believes that this is the sort of dream woman Wang might have dreamed had she been dreaming.

This leap of the author’s imagination may affront some readers’ sense of historical tact; others will probably be willing to suspend disbelief and defer to Spence’s intrepid mingling of fact and fancy. However, the passage noticeably lacks the realistic purposefulness which justifies Spence’s earlier imaginative touches and which brings so much life to his historical characters.

As soon as Spence returns to the actual death of woman Wang, his book is again grounded in the harshness of historical reality—a reality painstakingly reconstructed from Magistrate Huang’s account. Whether dreaming or awake, the woman Wang is suddenly and brutally attacked in her bed by Jen, who seizes her by the throat.

As Jen’s hands drove deeply into her neck, woman Wang reared her body up from the bed, but she could not break free. His hands stayed tight around her throat and he forced his knee down onto her belly to hold her still. Her legs thrashed with such force that she shredded the sleeping mat, her bowels opened, her feet tore through the mat to the straw beneath, but his grip never slackened and none of the neighbors heard a sound as woman Wang died.

In her death throes, then, woman Wang survives as the ultimate embodiment of this region of misery and era of grief. Just as Spence opens his brief history of T’an-ch’eng with the rumble of an earthquake and the shrieks of many perishing together, so does he complete his study with a solitary death, a pathetic crime of passion almost unnoticed in the vast empire of the ruler K’ang-hsi.

One may question the appropriateness of either of these macabre incidents as metaphors for China in the late seventeenth century. T’an-ch’eng, after all, was not a very representative district. Its land was rated lowest of all on the official nine-point fertility scale, and its inhabitants were constantly being taxed for transport services and highway maintenance because they had the misfortune to live on one of the main roads connecting Peking with Soochow. But we have too long been dazzled by the courts of the Manchu emperors to the north and the villas of the wealthy gentry farther south. Official histories notwithstanding, Spence has managed to turn from the very pinnacle of Chinese society to expose the lower depths at its base. With an artistry that dispels stereotypes of the common folk, he has run great risks as a historian to restore for us the barely preserved remnants of the poor and speechless, just as he manages to perpetuate the mute remains of woman Wang herself, thrown outside her hovel and left lying in the snow. “When she was found,” Spence tells us at the end, “she looked almost alive: for the intense cold had preserved, in her dead cheeks, a living hue.”

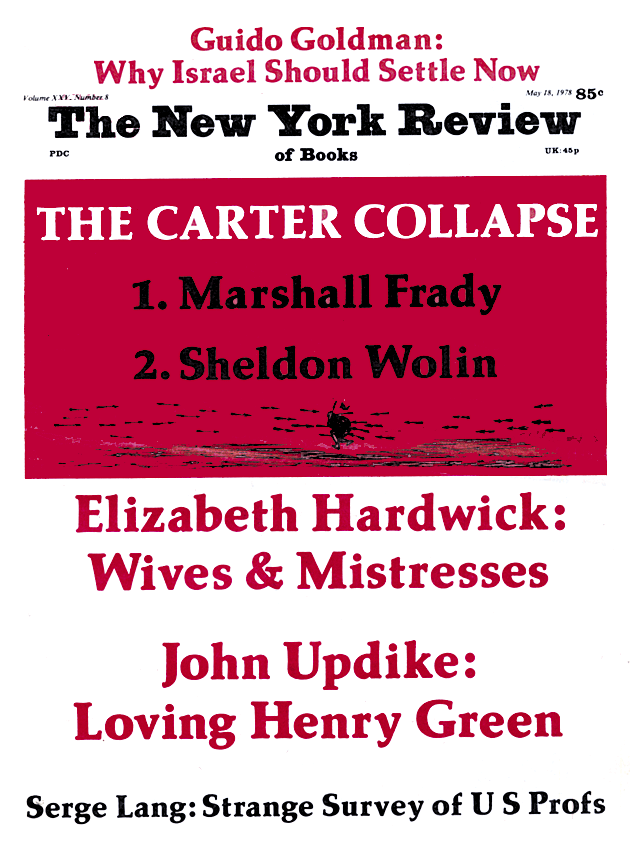

This Issue

May 18, 1978

-

1

Etienne Balazs, Chinese Civilization and Bureaucracy: Variations on a Theme, translated by H.M. Wright (Yale University Press, 1964), p. 135. ↩

-

2

Jonathan Spence, Ts’ao Yin and the K’ang-hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master (Yale University Press, 1966). ↩

-

3

Jonathan Spence, Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of K’ang-hsi (Knopf, 1974). ↩

-

4

Nelson L. Wu, “Tung Ch’i-ch’ang (1555-1636): Apathy in Government and Fervor in Art,” in Arthur F. Wright and Denis Twitchett, eds., Confucian Personalities (Stanford University Press, 1962), p. 262. ↩

-

5

The magistrate was Huang Liu-hung, also known as Huang Ssu-hu, who wrote a particularly vivid account of his tour of duty in T’an-ch’eng. The account was published in 1694 under the title Chü-kuan fu-hui ch’üan-shu [A Complete Book Concerning Happiness and Benevolence While in Office]. This work has attracted the attention of a number of Japanese social historians, and in 1974 Yamane Yukio compiled a new edition, which is the one used by Spence. ↩

-

6

This particular passage is a typical example of Spence’s ability to draw together bits of detail from a wide variety of sources to enliven his narrative. All that Magistrate Huang’s account reveals is that there was a new mat on the k’ang (heated bed) at the time of her death, and that at that time of year it was snowing. Mean temperatures for Shantung are drawn from Mark Bell’s nineteenth-century military report on Chihli and Shantung, and from John Lossing Buck’s volume of statistics accompanying his famous study Land Utilization in China (1937). For his description of the hovel, Professor Spence turns to Martin Yang’s twentieth-century village study of Taitou in Shantung (A Chinese Village), assuming (probably correctly) that there has been virtually no change in household construction between 1671 and 1944 in that part of China. ↩