Dr. Mario Jascalevich is on trial in New Jersey, charged with the murder, by curare poisoning, of a number of hospital patients in 1965 and 1966. His indictment was the direct result of a series of articles about the deaths of these patients written by a reporter for The New York Times, Myron Farber. Jascalevich’s lawyer. Raymond Brown, asked the trial judge to order Farber and the Times to turn over to the defense all the notes, memoranda, interview records, and other material Farber compiled during his investigation. Judge Arnold ordered. instead, that all such material be delivered to him, so that he himself could determine whether any of it was sufficiently relevant that it should be given to Brown. Farber refused this order, and was jailed for contempt, though he has since been released. The Times at first refused to deliver any material in its control, and was also cited for contempt, and forced to pay large daily fines. It has since handed over certain files, but the judge who imposed the fines, Judge Trautwein, charges that these files have been “sanitized,” and do not cure the contempt.

Farber and the Times appealed to the New Jersey Supreme Court (whose decision against their appeal was announced just as this issue of The New York Review went to press). They claim that Judge Arnold’s order was illegal on two different grounds. They argue that the order violated the New Jersey “Shield Law,” which provides that in any legal proceeding a newman “has a privilege to refuse to disclose” any “source” or “news or information obtained in the course of pursuing his professional activity.” They also argue that, quite apart from the Shield Law, the order violated their rights under the First Amendment to the US Constitution which provides for “freedom of the press.”

Each of these legal arguments is controversial. It is arguable that the Shield Law, in so far as it grants newsmen a privilege not to disclose information which might tend to prove an accused criminal innocent, is unconstitutional because it denies the accused a right to a fair trial guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment. If so, then Judge Arnold acted properly in asking that Farber’s notes and material be furnished to him privately so that he could determine whether any of them might tend to support Dr. Jascalevich’s innocence.

The First Amendment argument is weaker still. The Supreme Court in a 1972 decision. Branzburg v. Hayes. denied that the First Amendment automatically grants newsmen a privilege to withhold sources and other information in legal proceedings. Four of the five majority justices stated categorically that newsmen have no special privilege under the First Amendment beyond those of ordinary citizens. Mr. Justice Powell agreed that the reporters in the cases the Court was considering did not have the privileges they asserted. But he added, in a short and cryptic concurring opinion, that in some circumstances the First Amendment might require courts to protect newsmen from disclosure orders which serve no “legitimate need of law enforcement.” He spoke of the need to strike “a proper balance between freedom of the press and the obligation of all citizens to give relevant testimony with respect to criminal conduct.”

I do not interpret Powell’s opinion as recognizing a First Amendment privilege against disclosure ordered at the request of a criminal defendant, which is a very different matter from disclosure requested by the prosecution or other law enforcement agencies. State courts have disagreed about the correct interpretation of Powell’s opinion, however, and some have recognized a newsman’s privilege to withhold information requested by the defense when it appears that that information would be at best only tangentially relevant to the defense’s case. But even if this interpretation of Powell’s opinion is correct, Judge Arnold acted properly in ordering the material furnished to him privately, so that he could determine its relevance and importance to the defense, and the extent to which “freedom of the press” would be compromised by its public disclosure.

So it is at least doubtful that the legal arguments on which Farber and the Times rely are sound. The affair has been debated publicly, however, not as a technical legal issue but as an event raising important questions of political principle. Commentators say that the dispute is a conflict between two fundamental political rights, each of which is protected by the Constitution. Farber and the Times (supported by many other newspapers and reporters) appeal to the right of free speech and publication: they say that this right, crucial in a democracy, is violated when the press is subjected to orders that impede its ability to gather information.

Those who support Judge Arnold argue that the right of free speech and publication, though of fundamental importance, is not absolute, and must sometimes yield to competing rights. They therefore appeal to the principle, which they take to be paramount, that a criminal defendant has a right to a fair trial, which right, they say, includes the right to use any material that he might reasonably think supports his innocence. Both sides share the assumption that in these circumstances one or both of two important civil rights must be compromised to some degree, though they disagree where the compromise should he struck.

Advertisement

But the assumption they share is wrong. The privilege claimed by Farber has nothing to do with the political right to speak or publish free from censorship or constraint. No official has ordered him not to investigate or publish what he wants, or threatened him with jail for what he did publish, Judge Arnold’s subpoena is very different from the government’s attempts to stop The New York Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers or from the prosecution of Daniel Ellsberg or even the civil actions against Frank Snepp. It is, no doubt, valuable to the public that reporters have access to confidential information. But this is not a matter of anyone’s right. The question raised by the Farber case is not the difficult question of how to compromise competing rights, but the different question of how much the efficiency of reporters, valued by the public, must nevertheless be sacrificed in order to ensure that Dr. Jascalevich’s right to a fair trial is not compromised at all.

The public argument over the Farber case fails to notice an important distinction between two kinds of arguments that are used to justify a legal rule or some other political decision. Justifications of principle argue that a particular rule is necessary in order to protect an individual right that some person (or perhaps group) has against other people, or against the society or government as a whole, Antidiscrimination laws, like the laws that prohibit prejudice in employment or housing, can be justified on arguments of principle: individuals do have a right not to suffer in the distribution of such important resources because others have contempt for their race.

Justifications of policy, on the other hand, argue that a particular rule is desirable because that rule will work in the general interest, that is, for the benefit of the society as a whole. Government subsidies to certain farmers, for example, may be justified, not on the ground that these farmers have any right to special treatment, but because it is thought that giving subsidies to them will improve the economic welfare of the community as a whole. Of course, a particular rule may be justified by both sorts of arguments. It may be true, for example, both that the very poor have a right in free medical treatment and that providing treatment for them will work for the general interest because it will provide a healthier labor force.

But the distinction is nevertheless of great importance, because sometimes principle and policy argue in opposite directions, and when they do (unless the considerations of policy are of dramatic importance, so that the community will suffer a catastrophe if they are ignored) policy must yield to principle It is widely thought, for example, that crime would decrease, trials be less expensive, and the community better off as a whole if strict rules of criminal procedure that guard against the conviction of the innocent, at the inevitable cost of some acquittal of the guilty, were abandoned. But that is an argument of polley against these procedural rules and so it would not justify relaxing the rules if those who are accused of crime have a right (as most liberals think they do) to the protection the rules provide.

The distinction between principle and policy is relevant to Farber, because the arguments Farber and the Times make, In defense of a special newsman’s privilege to withhold information, are arguments of policy not principle. I do not mean that classical First Amendment arguments are arguments of policy; on the contrary the core of the First Amendment is a matter of principle, Individual citizens have a right to express themselves free from government censorship; no official may limit the content of what they say, even if that official believes he has good policy reasons for doing so, and even if he is right. Many Americans thought that it was in the national Interest to censor those who opposed the war in Vietnam. No doubt it was in the interest of the community of Skokie that the American Nazi Party be forbidden to march through that town. But as a matter of principle the war protesters had a right to speak and the Nazis a right to march, protected by the Constitution, and the courts so decided.

Advertisement

Reporters, columnists, newscasters, authors, and novelists of course, have the same right of free expression as other citizens, in spite of the great power of the press. Peter Zenger, the colonial publisher with whom Farber is sometimes compared, was jailed because he attacked the governor in print, and it was the object of the press clause of the First Amendment to prohibit that form of censorship. But newsmen do not as a matter of principle, have any greater right of free speech than anyone else.

There are, however, reasons of policy that may justify special rules enhancing the ability of newsman to investigate. If reporters confidential sources are protected from disclosure, more people who fear exposure will talk to them, and the public may benefit. There is a particular need for confidentiality, for example, and a special public interest in hearing what informers may say, when the informer is an official reporting on corruption or official misconduct, or when the information is information about a crime.

This is the argument of policy that justifies the Shield Laws many states have enacted, like the New Jersey law described earlier, and that justifies a variety of other special privileges newsmen enjoy. The Justice Department has adopted guidelines, for example instructing its agents not to seek confidential information from reporters unless the information is crucial and unavailable from other sources. The special position of the press is justified, not because reporters have special rights but because it. Is thought that the community as a whole will benefit from their special treatment, just as wheat farmers might be given a subsidy, not because they are entitled to it, but because the community will benefit from that.

The Times’s own arguments confirm that the privilege It seeks is a matter of policy not principle. It argues that important sources will “dry up” if Judge Arnold’s order is upheld. It is hard to evaluate that argument, though it does not seem powerful, even as an argument of policy. The Supreme Court’s decision in Branzburg v. Hayes, though its full force is debatable, plainly held that a reporter may be forced to reveal his sources when that information would be crucial to a defendant’s case, as determined by a trial judge. So even now reporters cannot, or should not, flatly promise an informer confidentiality. Any such promise must be qualified, if the reporter is scrupulous, by the statement that under certain circumstances, not entirely defined by previous court decisions, and impossible to predict in advance, a court many legally compel disclosure.

Judge Arnold’s order in the Farber case—that he be allowed to review it reporter’s notes to determine whether any material there would be important to the defendant’s case even though the defense has not demonstrated the probability of such material—arguably extends the Branzburg, limitations on confidentiality. But it is unclear how much the extension. If any, increases the risk that public disclosure will in the end be made, and unclear whether there are many informers not already deterred by Branzburg who would be deterred by the additional risk of disclosure to a judge alone. It is therefore entirely speculative how far the general welfare would suffer if the information that might be provided by informers of that special sort were lost.

In any event, however, this argument of policy, however strong or weak as an argument of policy, must yield to the defendant’s genuine rights to a fair trial, even at some cost to the general welfare. It provides no more reason for overriding these rights than the policy argument in favor of convicting more guilty criminals provides for overriding the rights of those who might be innocent. In both cases, there is no question of competing rights, but only the question of whether the community will pay the cost in public convenience or welfare, that respect for individual rights requires. The rhetoric of the popular debate over Farber, which supposes that the press has rights that must be “balanced” against the defendant’s rights. Is profoundly misleading.

It is also dangerous because this rhetoric confuses the special privileges newspapers seek, justified an grounds of policy, with genuine First Amendment rights. Even if this special privilege has some constitutional standing (as the four dissenting justices in Branzburg suggest), it has been and will continue to he sharply limited to protect a variety of other principles and policies. It would be unfortunate if these inevitable limitations were understood to signal a diminished concern for rights of free speech generally. They might then be taken as precedents for genuine limitations on that fundamental right—precedents, for example, for censorship of political statements on grounds of security.

It is both safer and more accurate to describe the privilege of confidentiality the press claims not as part of a constitutional right to freedom of expression or publication but as a privilege frankly grounded in efficiency, like the privilege the FDI claims not to name its informers, of the executive privilege Nixon claimed not to turn over his tapes, in Rovario v. US, the Supreme Court held that neither the FBI nor its informers have any right (even a prima facle right) to secrecy, although it conceded that for reasons of policy, it would be wise for coarts not to demand disclosure in the absence of some positive showing that the information would be important to the defense.

A president’s executive privilege is, as the Court emphasized in the Nixon case, not a matter of his right, or the right of the government as a whole. It is a privilege conferred for reasons of policy, in order that the executive may function efficiently, and it must therefore yield when there is reason to believe that a different public interest—the public’s interest in guarding against executive crime—demands constraint on the privilege. If the strong policy arguments in favor of executive privilege must yield when that privilege would jeopardize the prosecution of a crime, then a fortiori a newsman’s privilege, supported by weaker policy arguments must yield when it opposes a defendant’s right to gather material that might prove him innocent.

So the question raised by Farber is simply the question of how far the defendant’s moral and constitutional right to information extends, not simply against newsmen, but against anyone who has the information he wants. Several shrewd commentators, who do not dispute that the newsman’s privilege must give way if the information in question is vital, to the defense, nevertheless argue that Judge Arnold’s order was wrong in this case because Brown, the defense lawyer, had not shown any reasonable prospect that Farber’s notes were important to his case. They point out that it would be intolerable if every criminal defendant was able to subpoena all the notes and files of any newspaper which had reported on his case, in the thin hope that something unexpected might turn up. Lawyers call that sort of Investigation a “fishing expedition”; and courts have always refused defendants an opportunity to fish in anyone’s files.

Indeed, it has been suggested that Brown made his request not because he believed he would discover anything useful to his client but because he hoped that the request would be refused so that he could later claim, on appeal, that the trial was unfair. (It has also been suggested that Judge Arnold ordered the material requested to be shown to him privately, instead of rejecting the request outright, to frustrate this supposed strategy.) It would have been better (these commentators suggest) for the judge to require some initial showing by the defense why it was reasonable to suppose that the files would contain relevant material, before ordering the files to be shown to him alone.

Even this more moderate position seems wrong on the facts of this particular case, however, Farber’s investigations were responsible for the police reopening a murder case years after their own investigation had been suspended. He accumulated a great deal of information not previously available, and it is not disputed that this information was the proximate cause of the indictment. In particular, Farber discovered and interviewed witnesses who now appear to be vital to the prosecution and who might have made statements to him that either amplified or contradicted their testimony or the accounts he published. There is, of course, no suggestion here that Farber has deliberately withheld anything that would be helpful to the defense. But he, like any other reporter, exercised editorial judgment, and he should not, in any case, be expected to the sensitive to the same details that would interest a good lawyer whose client is on trial for murder.

These facts are sufficient to distinguish the present case from imagined cases in which the newspaper has done not much more than report on facts or proceedings developed or initiated by others. Judge Arnold held that Farber’s unusual role in the case in itself constituted a showing of a sufficient likelihood that his files contain material a competent defense lawyer should see; sufficient at least to justify the judge’s own preliminary examination of the file. Perhaps he would have required a further showing of probable relevance, or a more precise statement of the material sought, if the trial were not a trial for murder. Perhaps another judge would have required some further precision even in a murder case. No doubt Judge Arnold should have held a hearing at which lawyers for Farber and the Times could have put their legal objections and asked for greater specificity before they were found in contempt. (The New Jersey Supreme Court has now held that in the future such a hearing must be held if requested.) Nevertheless Judge Arnold’s decision, that the facts of this case in themselves constitute the necessary demonstration, shows commendable sensitivity to the problems of a defendant faced with an investigation whose very secrecy deprives him of the knowledge he needs to show his need to know.

But it was not, I should add, reasonable to order Farber to jail or to order the Times to pay punitive dally fines while their legal arguments were pending before appellate courts. They relied a good faith on their understanding of the shield Law and the First Amendment,* It is useless to say that they should have compiled with Judge Arnold’s order, and contested its legality later. They believed that their rights would have been violated, and the principles at stake compromised, even by an initial compliance with the judge’s order. They were wrong, but our legal system often gains when people who believe that law and principle are on their side choose not to comply with orders they believe illegal, at least until appellate courts have had a chance to consider their arguments fully, and it served no purpose to jail Farber or fine the Times before their arguments were heard, Certainly it was not necessary to defend the dignity of Judge Arnold’s court or of the criminal process. If Farber and the Times make immediate appeal to the US Supreme Court, the New Jersey Supreme Court, even though it has upheld Judge Arnold’s decision, should stay execution of further fines, and of its order that Farber return to jail, pending an expeditious ruling on that appeal.

The courts must at all costs secure Dr Jascalevich’s right to a fair trial. But within that limit they should show, not outrage, but courtesy and even gratitude to people like Myron Farber who act at personal sacrifice to provide the constant judicial review of principle that is the Constitution’s last protection

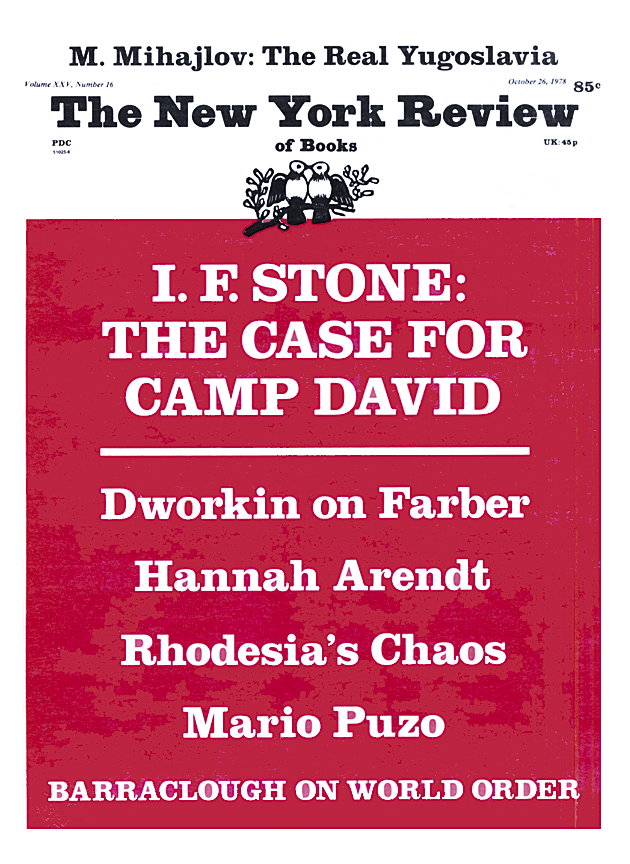

This Issue

October 26, 1978

-

*

Federal Judge Laccy, in a hearing on Farber’s petition for habeas corpus, emphasized that Farber had undertaken to write a book about the Jascalevich case. Many newspapers and columnists have since assumed that the proposed book weakens Farber’s case either legally or morally. It seems to me, on the contrary, almost irrelevant. Farber’s contract with his publisher does not make the book’s publication conditional on the conviction of Jascalevich, and there ie: no shred of evidence either that Farber will publish in the book material that he sought to withhold from the court or that he has any financial or personal stake in Jascalevich’s conviction. There is no reason to doubt that Farber would have acted just as he did even if he had not planned to write a book. ↩