I

Until fairly recently the history of Catholicism in Elizabethan and Jacobean England was conceived largely in terms of hagiology. From the first history of the English Jesuits, by Father Henry More, grandson of Sir Thomas, in 1635, to the biography of the Blessed Edmund Campion by Evelyn Waugh, written exactly 300 years later, Catholic historians concerned themselves mainly with saints and martyrs, men of action and men of vision, with the pious great and the pious poor. They said little about poets and even less about artists or musicians; traditional historians have never been much interested in the arts. No doubt if they had found a Shakespeare among the faithful they would have made much of him. But they did not. They found only the Jesuit poet Robert Southwell; and it seemed rather beside the point to award Father Southwell the laurel since God had reserved for him the vastly greater glory of a martyr’s crown of thorns.

In fact the English Catholic community had among its members a much more brilliant ornament in the field of the arts. William Byrd, the premier figure of Elizabethan and Jacobean music, was also one of the greatest of all European composers of the time and arguably the greatest English composer of all time. But the art of music has been slow to acquire the prestige of poetry; when music did gain it (or something like it) Byrd’s music was no longer well known or easy to come by; and when this music at last became more generally available, the key to its interpretation as a Catholic statement was still lacking. And so Catholic historians have paid Byrd almost no attention.

Music historians, though they have paid more attention, have failed or refused to see the composer clearly enough against the background of his religion. It is not that his religious convictions have ever been in the slightest doubt. He wrote great quantities of Latin liturgical music for Catholic services, and a high proportion of the records of his life that have come down to us concern his Catholic activities and activism. So many, indeed, that in the standard life-and-works by E.H. Fellowes, which has three chapters on the life, one of these chapters is devoted entirely to “Byrd’s Association with the Catholics.” But as the word “association” in this context perhaps already suggests—would one speak of “Milton’s Association with the Puritans”?—Byrd’s Catholicism was something that Fellowes could never take quite seriously. A decidedly stiff-necked Victorian clergyman, the author of a major work on Anglican Cathedral music, he never missed an opportunity of pointing out that Byrd also wrote admirable music for the Church of England liturgy—though to be sure, there was very much less of this than of the Catholic sacred music. In the early part of this century Fellowes performed wonders in the publishing and publicizing of Byrd’s music, but he did this in an ecumenical spirit which seriously obscured its fundamental sectarian nature.

Thanks partly to Fellowes’s work, it is now customary, at least in English and American musical writings, to rank Byrd with the main masters of late sixteenth-century music—with Palestrina, Lassus, and Victoria. He is so ranked, for example, in Howard Mayer Brown’s recent Music in the Renaissance (1976). This is not, I think, a case of mere chauvinism on the part of English scholars and critics, and mere superstition on the part of Americans. A study just published of The Consort and Keyboard Music of William Byrd,1 by Oliver Neighbour, illuminates sharply the greatness of Byrd’s instrumental music; he was the first major composer to devote a substantial effort to music without words. Getting Byrd’s Latin sacred music into correct focus—a Catholic focus—will allow a clearer view of another body of his music which is equally great. And when this music is in its correct focus it also will be seen to illustrate the responses of the Elizabethan Catholic community in a unique way. Resources are available to art and to artists that are not available to even the greatest saints and heroes of traditional Catholic history.

II

The course of Byrd’s life and the history of Elizabethan Catholicism intersect most dramatically in 1580–1581, at the time of the fateful Jesuit missionary expedition of Fathers Robert Persons and Edmund Campion. These were two very remarkable men, and Campion, especially, who had been the most brilliant figure at Oxford in the 1560s, seemed to have a disquieting success among the country gentry, the clergy, and academics. After about a year he was betrayed, apprehended, interrogated with the help of the rack, and finally condemned to die with two other priests at a great public execution in London. Campion started his final address from the scaffold with words of St. Paul to the Corinthians, “Spectaculum facti sumus Deo, angelis, et hominibus,” “We apostles are made a spectacle unto God, unto His angels, and unto men”—but this was brutally cut short. The three men were hanged, drawn, and quartered, and their dismembered bodies nailed to a gate on Tyburn Hill.

Advertisement

This triple execution rocked England and set off a storm of protests from abroad. There had been nothing like it since the days of Mary Tudor. Tracts were written back and forth about the event, and stories began to grow up around it. One of these concerned a young Catholic gentleman named Henry Walpole—“Cambridge wit, minor poet, satirist, flaneur, a young man of birth, popular, intelligent, slightly romantic,” as Waugh describes him. Standing near the scaffold when Campion’s body was being butchered, he saw a drop of blood spurt onto his coat. Profoundly shaken, he went home and sat up that night writing an extremely long, anguished poem about Campion, Why do I use my paper, ink and pen, which caused a scandal. The printer of it had his ears cut off, and Walpole had to flee the country. Eventually he became a Jesuit himself and returned to England to meet the same fate as Campion.

Byrd set this notorious poem to music, and the setting certainly did not escape notice. Another future Jesuit, Thomas Fitzherbert, remarked that “one of the sonnets [on Campion’s death] was presently set forth in music by the best musician in England, which I have often seen and heard,” and no doubt Fitzherbert heard it before 1582, when he too left England. Also, at around this same time, Byrd wrote an extended Latin motet, Deus venerunt gentes, which must also rage and lament for Campion under the cover of some blameless verses from Psalm 79:

O God, the heathen have set foot in thy domain, defiled thy holy temple and laid Jerusalem in ruins. They have thrown out the dead bodies of thy servants to feed the birds of the air; they have made thy saints carrion for the wild beasts. Their blood is spilled all around Jerusalem like water, and there was no-one to bury them. We suffer the contempt of our neighbors, the gibes and mockery of all around us.

We have here the unburied bodies nailed to the gate, the blood that spurted on Walpole, the protests from “our neighbors” abroad, and even an allusion to Campion’s speech from the scaffold: for the last verse begins in Latin “Facti sumus opprobrium vicinis nostris” and I do not think it can be a coincidence that this comes so close to Campion’s “Spectaculum facti sumus Deo, angelis, et hominibus.”

It is likely enough, I suppose, that Byrd too stood in the rain and the mud at Tyburn to witness Campion’s martyrdom. It seems very likely that this affected him much as it affected Walpole. Not that he ever went abroad to become a missionary; Byrd was one of those who stayed at home, and prospered, and made his uneasy peace with the system. But after 1581 his religious commitment hardened decisively. Whether it is technically correct to speak of a “conversion” in his case, as in Walpole’s, is not clear. But with Byrd as with Walpole we cannot fail to detect a profound new sense of devotion to the Catholic faith and the Catholic cause.

Born in 1543, Byrd was just old enough to have been brought up as a choirboy under the old religion—the old religion which Mary Tudor restored, between 1553 and 1558, with special zeal. His first position was in the new Anglican disposition; he was appointed organist-choirmaster of Lincoln Cathedral in 1562. The personality that we are able to glimpse from Lincoln records is not distinguished by any unusual spirituality, but rather by a certain contentiousness and a precocious talent for the great Elizabethan art of applying influence—a talent that obviously stood him in very good stead during his later, intransigently Catholic years. Lincoln appointed him at a higher salary than his predecessor, with a lease of land thrown in to sweeten the contract, and when he left for the Chapel Royal in 1572 he pulled strings from London so that he actually continued to draw a salary from Lincoln for nearly ten years more.

In London Byrd’s star rose rapidly. He made connections with powerful lords such as the earls of Essex and Northumberland, and acquired more leases. He was appointed joint organist of the Chapel Royal, sharing the post with his master Thomas Tallis, who was then around seventy years old. With Tallis, too, he secured a patent from the Crown for music printing—a trade with little history in Britain up to this time. The monopolists’ debut was a joint publication of Latin motets, the Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur of 1575, dedicated to Queen Elizabeth and designed to show the world what excellent music Britain could produce. So at least we are told by the elaborate prefatory matter, which goes on for six pages. And influential persons were enlisted to fill these pages: a courtier and dilettante composer named Sir Ferdinando Richardson, and the important educator Richard Mulcaster. One has the feeling it was Byrd, not the aging Tallis, who did the enlisting.

Advertisement

So far it had been a worldly career, with scarcely any signs of Catholic leanings. In 1577, however, Byrd’s wife was first cited for recusancy, that is, for refusing to attend Church of England services as required by law. It was a common pattern for Catholic wives to stand on principle while their husbands, who had much more to lose, attended the required services as “church-papists.” After 1580 the signs multiply. Clearly the authorities were now more vigilant, but clearly also Byrd was more engaged.

His house was watched and on one occasion searched. His servant was caught in a raid. His one surviving letter, dated 1581, sues on behalf of a beleaguered Catholic family. In 1586 he was one of a small group assembled to welcome two notable Jesuits to England, Fathers Southwell and Henry Garnet. Byrd must have been highly regarded among the Catholics to have been summoned on this occasion. He himself was cited for recusancy in 1585, and bound in recognizance of the staggering sum of £200 for the same crime two years later. (He may never have paid it.) Still to come, in his declining years, was the accusation that he had “seduced” certain servants and neighbors away from the Church of England; but Byrd seems always to have stayed clear of actual arrest or serious harassment.

Byrd’s new religious conviction was expressed in music—in a remarkable series of Latin motets composed in a new style, and with texts of an entirely new kind. These texts seem to voice prayers and protests, which are sometimes general and sometimes more specific, on behalf of the Elizabethan Catholic community.2

Some of these motets speak of a “congregation” or “God’s people” who await liberation. Thus Domine praestolamur:

O Lord, we await thy coming, that you may at once dissolve the yoke of our captivity. Come, o Lord, do not delay. Break the bonds of your servants, and liberate your people.

Byrd harps on the theme of the coming of God in various moods—supplicatory, as in the text above, or confident, in Laetentur coeli:

Let the heavens rejoice and the earth exult…for the Lord is coming…

or didactic, in Vigilate:

Be wakeful, for you know not when the lord of the house is coming, in the evening, in the middle of the night, at cock-crow, or early dawn; be wakeful, lest when he come suddenly he may find you asleep….

Several impressive motets refer to the Holy City, Jerusalem, and the Babylonian captivity: a transparent metaphor for the Catholic situation in Britain, though of course it could also be turned in other directions. Ne irascaris Domine, which is dated 1581 in two independent manuscripts, was and still is the most popular of these “Jerusalem” motets.

Other texts, of which the most sensational is Deus venerunt gentes, the Campion lament mentioned above, are more explicit in reference. Two of Byrd’s greatest motets, Haec dicit Dominus and Plorans plorabit, tell in the one case of the progeny of lamenting Rachel who are promised their patrimony, and in the other of the king and queen who hold the Lord’s flock captive—this motet appeared as late as 1605—and whose proud crowns have fallen. Both texts are drawn from Jeremiah; both seem frankly political in intent.

Boldest of all, perhaps, is Circumspice Hierusalem, a text from the Apocrypha which can only refer to the Jesuit missionaries:

Look around toward the East, o Jerusalem, and see the joy that is coming to you from God! Behold, your sons are coming, whom you sent away and dispersed; they come gathered together from the East to the West, at the word of the Holy One, rejoicing in the glory of God.

“Whereas I have come out of Germany and Boëmeland,” wrote Campion in the document known as Campion’s Brag, a powerful open letter to the Privy Council, “being sent by my Superiors, and adventured myself into this noble realm, my dear country, for the glory of God and benefit of souls….”

Interestingly enough, there is a contemporary acknowledgment of Byrd’s covert use of Latin motets for personal or political statements. It is a covert acknowledgment, of course. In 1583 a grandiose motet was sent to him by the great Netherlandish composer Philippe de Monte, chapelmaster to the Holy Roman Emperor. The motet’s words are pointedly rearranged from the most famous of the psalms of captivity, Super flumina Babilonis (By the waters of Babylon, Psalm 137):

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. There they that carried us away captive required of us a song. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

A year later Byrd sent back a magnificent answering motet as though to a challenge:

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, o Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy….

Byrd’s Quomodo cantabimus includes a three-part canon by inversion: as though to assure Catholic Christendom that he had not hung up his harp, that his faith was firm, and that his hand had lost none of its cunning. Seldom does the murk of under-documentation allow so sharp an insight into the Elizabethan musical condition as is afforded by this exchange between two great Catholic composers.

Byrd’s motets of the 1580s employ a new musical style, on which his whole political endeavor depended. (We should speak more strictly of a maturing of tendencies already evident in the Cantiones of 1575—a brilliant, experimental, uneven group of compositions.3 ) There is much that is historically important about this style, as far as the development of English music is concerned: its refinement of the basic medium of imitative polyphony, its command of the subtle distinctions between various homophonic and half-homophonic textures, and in general its superb native reinterpretation of the classical mid-century idiom of Continental Europe.

But perhaps its most important new feature is its new sensitivity to verbal texts. It is only with the Tallis-Byrd Cantiones of 1575 and especially with Byrd’s motets of the next decade that English music is “framed to the life of the words,” as Byrd himself was to express it some time later. This “framing” we usually associate with the madrigal, a secular genre which had served Italian composers since the 1530s as an endlessly fertile field for the investigation of word-music relationships. But madrigals are not known to have been written in England before the 1590s. Ahead of the English madrigalists, Byrd was already practicing the expressive and illustrative rhetoric of Continental music in his sacred motets of the 1580s.

This rhetoric made for their impact. Byrd did more than provide significant texts with beautiful music. It was music of a rhetorical vividness that was all but unprecedented on the English scene, and so it was music of unprecedented power. Again and again, when the motets break into their great supplications—“Have mercy on us, o Lord,” “Lord, do not forget thy people,” and the like—the music breaks out of the prevailing polyphonic discourse into powerful chordal passages of direct outcry. When the text of Ne irascaris Domine says “Zion is a wilderness” Byrd frames these words with harmonies and textures that are unforgettably bleak and hollow. When the Lord is urged to arise (“Exsurge Domine“) the melody mounts up the scale in excitement, and when it is promised that he will not delay (“et non tardabit“) the rhythm races in frantic double-time note values. And when St. Mark warns us to be wakeful, lest when the Lord arrive he find us sleeping, Byrd with grim humor writes music that drones or snores and is then cut short by vivid shouts of “Vigilate! vigilate! vigilate!”

The stylistic point is important to make because, of course, the expressive style is at the heart of Byrd’s unique contribution to these motets. The texts themselves may not have been his personal choice. They could have been given to him by his patrons or his priests (though some I believe he must have chosen himself, because only a musician would have been likely to know their sources). Whoever chose the words, however, Byrd brought them to life in a way that had previously been unknown in English music. These motets must have seemed extraordinarily moving and powerful to their first listeners. Indeed they still seem extraordinarily moving and powerful today.

III

At the end of the 1580s Byrd for the first time began issuing his music in a systematic way. He published two books of English songs and two of Latin motets, and also supervised a beautiful manuscript collection of his virginal music, My Lady Nevells Booke. It is hard to escape the impression that the composer was setting his house in order—writing finis, as it were, to a chapter of his creative career. And indeed in his fiftieth year, 1593, Byrd obtained a farm in the village of Stondon Massey in Essex and went there to live. After this move, the music that he wrote was of a different kind than he had cultivated before.

Situated between Brentwood and Chelmsford, the county town, Stondon is about twenty-five miles from Westminster—that is, about twice as far as Byrd’s previous home (which was at Harlington, near the present Heathrow Airport). The farm was a good-sized one, and it looks as if the composer were going into a semi-prosperous semi-retirement. Though he certainly did not resign his position in the Chapel Royal, it seems he was not often there, for his name is usually missing from the memorials and petitions signed by all the other members. His printing monopoly was not renewed; henceforth he is not much heard of around London. But I believe that this semi-retirement was not the prime consideration, but rather a symptom, and that the real significance of the farm at Stondon was not its remoteness from London but its proximity to the great manor house at Ingatestone, just a few miles distant.

Ingatestone Hall had been built by Sir William Petre, Secretary of State under Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, and Elizabeth. His son Sir John was a circumspect Catholic and a patron of Byrd’s. (The first document linking their names dates from the fateful year 1581.) Lady Mary was less circumspect. The Petres presided over a Catholic community centered around their Essex estates of Ingatestone and Thorndon; and what I suspect is that Byrd moved from Harlington expressly to join this community and participate in the Catholic life there. If so, this clearly marks a new deeper commitment by William Byrd to his religion.

The social historian John Bossy has given us a remarkably full picture of Catholic life in England at this time.4 A large proportion of the Elizabethan gentry retained Catholic sympathies, and those that were really serious about religion found it possible to work out a modus vivendi within the system. They had to stay out of public life and retire to their country estates, and they might have to put up with fines and harassment—and they were well advised to stay clear of their inflammatory sons and cousins who went abroad to become Jesuits and returned, like Henry Walpole, to make life difficult for the authorities and for the Catholic minority alike. That is a lot. But if they were prepared to make these sacrifices, the Catholic gentry were pretty much left to supervise the lives of their families, servants, and tenants according to Catholic principles as they saw them.

The main principles, and the main preoccupations, according to Bossy, were three. First, the Catholic gentry were naturally determined to raise their children in the faith. Second, they labored to institutionalize a daily routine in accordance with the elaborate Catholic calendar of those days, with its feast and fast days, its rogation times, and its seasons of abstinence from meat. The daily texture of their lives grew more and more distinct from that of the Anglican majority. Third, they struggled to maintain undercover Catholic services. They set up “Mass-centers” in attics and barns, furnished with the necessary consecrated church furniture, vestments, and the like, and they harbored traveling or circuit priests, even sometimes resident ones. Mass was celebrated strictly according to the Roman liturgy, of course. On great occasions such as Christmas and Easter, it was desirable for Mass to be sung with a choir in as festive and ornate a fashion as one remembered from the days of Henry VIII and Queen Mary. Then the Petres were inclined to seek out the quiet of Ingatestone, away from the main road and less public than their principal seat at Thorndon.

The impression that Byrd entered into a life of this kind rests not only on the fact that he moved to Stondon—it appears, incidentally, that he brought his entire extended family along with him—but also on the kind of music he wrote after the move. Instead of covert political motets and the other types that he had cultivated in the 1580s—mainly settings of penitential texts, which were widely popular in the sixteenth century, with a few didactic homilies and general songs of praise—he now turned almost exclusively to liturgical items for particular Catholic services. And once again, as at the beginning of the 1580s, the change in text repertory was accompanied by a change in musical style.

His three settings of the Ordinary of the Mass date from 1592–1595. 5 They contain the music by which he is perhaps best known today: direct, concise, eminently “functional,” even austere, yet infused with a remarkable quiet fervor. In the next decade he produced his magnum opus the Gradualia, a great collection of more than a hundred motets for the Proper of the Mass (those sections of the service which change according to the season). The entire Church year is covered; one remembers Bossy’s point about the Catholics’ preoccupation with the Church calendar. There are motets for Christmas, Epiphany, the Purification, Easter, Ascension, Whitsun, Corpus Christi, All Saints, and various feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary—as well as two feasts of special importance to the Catholics, Sts. Peter and Paul and St. Peter’s Chains. Byrd sets the communion of these two feasts, Tu es Petrus, with the greatest of verve: “You are Peter, the rock, and on this rock I will build my Church.”

Liturgical music is written to be used in a liturgy. Byrd’s Masses and Gradualia motets were written for services held at the clandestine Mass-centers of Catholic England. He says plainly, when dedicating book two of the Gradualia to his patron, that its contents “have mostly proceeded from your house, which is most friendly to me and mine”—Ingatestone Hall, where Byrd and his family must have worshipped regularly. “These little flowers are plucked as it were from your gardens and are most rightfully due to you as tithes.” But the fact that this music was printed shows that it was destined to be sung elsewhere, too. “We kept Corpus Christi Day with great solemnity and music,” writes Father Garnet in 1605, “and the day of the Octave made a solemn procession about a great garden, the house being watched, which we knew not until the next day.” Was the music taken from the Corpus Christi section of the Gradualia, published only a few months earlier? A few months later Garnet, who had an “exquisite knowledge of the art of music,” was together with Byrd at a musical gathering in London.

And a few months later than that, the Gunpowder Plot had brought down Garnet and all possible Catholic hopes for a new restoration. It should already have been clear enough after the defeat of the Armada in 1588 that the best that could be hoped for was the maintenance of a Catholic way of life in a minority status. In the 1580s, when many Catholics still regarded the eclipse of their faith as a temporary aberration, Byrd spoke for them in motets of extraordinary power. Then in the 1590s he turned from these motets of anguish and anger to motets and Mass sections celebrating the Catholic rite in perpetuity. In this turn we may see a new acceptance of the inevitable on the part of his essential patrons among the Catholic gentry.

His own acceptance can be seen in the move to Stondon, the withdrawal from artistic life in London, and the establishment of closer ties with the Catholic community under the Petres. There is one nonliturgical motet in the Gradualia that deserves special notice—one nonliturgical motet among a hundred that are strictly bound to the liturgy:

One thing I ask of the Lord, one thing I seek: that I may inhabit the house of the Lord all the days of my life, to gaze upon the beauty of the Lord and seek him in his temple.

These words from Psalm 27 would seem to speak with uncommon directness of Byrd’s own condition.

IV

One might say that Byrd had come full circle, in that he was now treating the same Catholic liturgical texts that he had come to know as a choirboy in the time of Queen Mary. But of course the music he wrote for these texts in the 1590s was not like the music he sang in the 1550s. Much as the Catholics may have wished to return to the medieval order, they could not do this in their music any more than they could in their political accommodation. The clandestine Masses at Ingatestone, always in danger of exposure by spies, had no leisure for the grandiose, drawn-out, florid music of Tallis and his generation. Byrd’s Masses are a great deal simpler and more concise. Some of his Gradualia motets are positively aphoristic.

There could also be no return to the older Tudor composers’ attitude toward the words. For them, the actual meaning of the words in a liturgical text mattered less than the function of that text as a unit in the ritual. But for Byrd the word was primary. “There is such a profound and hidden power to sacred words,” he observes in the dedication to the Gradualia—it is a famous and beautiful statement—“that to one thinking upon things divine and diligently and earnestly pondering them, the most suitable of all musical measures occur (I know not how) as of themselves, and suggest themselves spontaneously to the mind that is not indolent and inert.” The expressive rhetoric that he had developed in the 1580s still illuminates the liturgical texts of the Gradualia—texts such as Ave verum corpus, O magnum misterium, Iustorum animae, and Tu es Petrus, to mention only some of the most familiar. It even illuminates the words of the Ordinary of the Mass, which served Catholic composers on the Continent as the commonest of clay for the building of one purely musical construction after another. But Byrd was a Catholic composer who could not and did not take the Mass for granted.

His late Latin sacred music was, in short, Catholic liturgical music in a new manifestation: just as Ingatestone was not really a continuation of the old late-medieval order, but the beginning of a new regime of Catholic life which would, in fact, continue with relatively minor modifications until the nineteenth century.

Anyone who knows anything of the Gradualia will remember the luminous “alleluia” sections in Sacerdotes Domini, Non vos relinquam orphanos, Constitues eos, and many other pieces. Byrd’s treatment of these alleluias—there are nearly eighty examples—can perhaps be taken as emblematic of his whole endeavor in the late sacred music. He never thought to cut corners by writing a da capo indication for one of these alleluias, though in many cases the liturgical rubrics would have made this perfectly appropriate; he seems to have been fascinated by the problem of setting the same word in dozens of different ways, as though absorbed in the mystery of the inexhaustible renewal of praise. The language of the Seven Penitential Psalms and the Book of Jeremiah echoes through the texts of Byrd’s earlier motets. What stays in the mind from the Gradualia is the endlessly repeated, endlessly varied acclamation “alleluia” and the act of ritual celebration which it embodies.

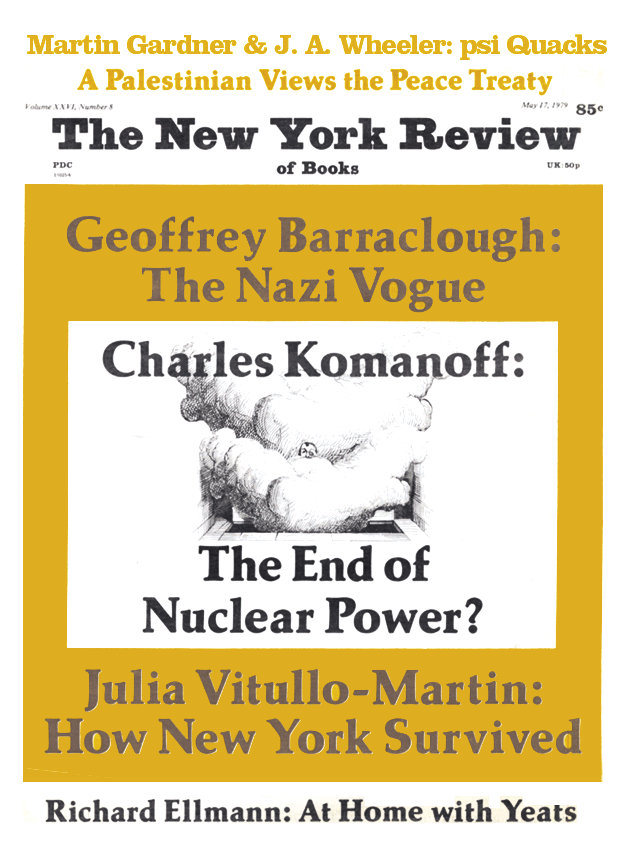

This Issue

May 17, 1979

-

1

Faber & Faber, 1978; University of California Press, 1979. ↩

-

2

The argument justifying such an interpretation of Latin motet texts—texts that are in many cases drawn directly from the Bible—is an intricate or at least a laborious one, which cannot be adequately summarized here. I went into the matter at some length in an essay for Studies in the Renaissance, IX (1962), pp. 273–308. ↩

-

3

An excellent edition of these motets, edited by Craig Monson, has just appeared as volume 1 of a new complete edition of Byrd’s music, The Byrd Edition (Stainer & Bell, London, 1978). ↩

-

4

In The English Catholic Community, 1570–1850 (Oxford University Press, 1976). ↩

-

5

There have recently been two particularly fine recordings of the Masses: the Three-Part Mass by the Pro Cantione Antiqua, directed by Bruno Turner (DGG Archive 2533 113: with the Tallis Lamentations of Jeremiah), and the Four- and Five-Part Masses by the Choir of Christ Church, Oxford, directed by Simon Preston (Argo ZRG 858). No other current listings of Byrd’s Latin sacred music can be strongly recommended, though the old recording of the complete Tallis-Byrd Cantiones by the Cantores in Ecclesia, directed by Michael Howard, provides a valuable entrée to this repertory (Oiseau Lyre SOL 313). ↩