The pain of Cambodia is as intense as ever. Food sent from foreign countries to the authorities in Phnom Penh has not been reaching hungry Cambodians. They are threatened by another famine this summer. Food sent across the border from Thailand has been reaching Cambodians. But it has also been reaching the Khmer Rouge, who are stronger than at any time since the Vietnamese invaded to crush them eighteen months ago. A political solution to the country’s plight seems more distant than ever.

The Cambodian relief operation is already one of the most expensive in history. By the end of this year the international organizations alone will have spent around $500 million over fifteen months, or $100 a head for the estimated five million Cambodians who have so far survived the last ten years. (The Bangladesh relief efforts, by contrast, cost about $22 a head over a three-year period.)

On May 26 fifty-nine Western and Asian countries held a humanitarian conference in Geneva on Cambodia; they pledged more money (not enough) to the relief effort. This commitment was made in a mood of anger and frustration with the Vietnamese and their government in Phnom Penh. The two governments had refused to attend the conference, although they will be the largest beneficiaries of the new aid pledged. There was, they said, nothing to discuss, and they denounced the meeting as an imperialist plot. Cambodia was represented at this “humanitarian” conference by the Khmer Rouge (“The Government of Democratic Kampuchea”), who still hold the country’s seat at the United Nations.

Most of the delegates made stirring speeches in defense of the Cambodian people and in criticism of Vietnam. At the back of the hall the Khmer Rouge delegation smiled and clapped effusively. It cannot be said that other delegates clustered around them; for the most part the Khmer Rouge representatives wandered around alone soliciting handshakes and smiling ingratiatingly. They invited me back to their mission. Their ambassador at large, Thioun Moeum, a highly intelligent graduate of the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, spent almost three hours assuring me that although certain “errors” had been committed in the past, their rule would be much more restrained in the future. He was as bland as he was clever.

When I reminded him that to many people the regime he represented was on a par with Hitler’s, he merely smiled, shrugged, and promised that they now took account of Western concerns. Talking with him I found exhausting and very depressing. After I left he flew to Bangkok. From there Thai authorities took him to the Cambodian border and he returned to the jungle, to rejoin Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, and the thirty to forty thousand guerrillas they now have fighting the Vietnamese.

The relief operation has been underway since last fall. UNICEF and the International Red Cross (ICRC) have shipped food and other supplies to Phnom Penh and to Cambodia’s main seaport, Kompong Som. So have Oxfam and other groups. UNICEF and ICRC, together with voluntary agencies like CARE and World Relief, have also been pushing supplies across the Thai border.

It has, however, been impossible to monitor the distribution of supplies. At the Thai border large quantities of supplies have been stolen by corrupt officials and traders. More have been “diverted” to the Khmer Rouge. In Phnom Penh a disproportionate amount of the aid has been used to feed government workers, and far too little has been reaching ordinary peasants. As well as being one of the most expensive relief efforts, this is also one of the least well observed and audited.

The problem of food turns on numbers. At the beginning of 1980 the joint UNICEF-ICRC mission in Phnom Penh reckoned that, in order to provide a minimal ration of 400 grams a day, the West needed to send about 200,000 tons of food in 1980 to supplement the supplies available internally and those provided by the USSR and Vietnam.

This was too low an estimate. Last year’s harvest was poor, and 250,000 tons are needed. So far this year deliveries have fallen far short of the target. Now 35,000 tons must be delivered and distributed every month. This does not seem possible, and the result is that thousands will starve.

It is not just food that is required. In recent weeks, there has also been a desperate need for rice seed. The agencies have been engaged in a hectic, often incompetent, and very costly race against the seasons to try to get seed into the country in time for the annual planting. Cambodia’s main rice crop is planted each year in May and June as the monsoon floods the land. Before the war began in 1970 Cambodia’s seven million people planted about three million acres and produced enough rice for export. By the end of the war the agricultural system had been destroyed and the country was almost totally dependent upon US imports. The rice yields during the years of rule by the Khmer Rouge between 1975 and 1979 remain unknown. Although some effort was made to rebuild agriculture (often in grandiose, ineffective ways) little food was given to the people. Last year, in the confusion and fighting following the Vietnamese invasion, almost no planting was done. The yield was only about 10 percent of normal and it has now all been consumed.

Advertisement

The relief program launched last October was planned for only six months, and therefore inadequate attention was given to procuring seed for the 1980 season. Then the UN Food and Agriculture Organization decided to ship some 30,000 tons of seed into Cambodia by the end of April. This would have planted about a million acres and yielded about 200,000 tons of rice. At the same time the Vietnamese and Russians said they each would ship about 10,000 tons of seed.

Some Vietnamese seed has been arriving, although no one knows how much. But the FAO program ran into extraordinary delays, many of them because of gross mismanagement. By mid-March FAO had bought only 3,000 tons of seed. Along with Oxfam, it was negotiating for more in Thailand. But by then only about eight weeks remained for 30,000 tons to be found, bought, shipped, unloaded, and distributed to farmers.

It was clear that the ports of Kompong Som and Phnom Penh were too blocked up and inefficiently run to accommodate all of the seed finally ready for shipment. Under pressure from the US Embassy FAO bought seed that was intended to be carried across the Thai border into Cambodia along the unofficial land routes that the Vietnamese have tolerated since last autumn. At the same time an airlift from Bangkok to Phnom Penh was organized by the International Red Cross.

About 15,000 tons of seed have now been transported over the border by oxcart, bicycle, and foot; 5,000 more have been flown in. More could have come by air, but the Vietnamese refused to allow planes to fly direct from Bangkok. They had to circle out over the South China Sea and then back up the Mekong River, thus doubling the flight time. The cost of the airlift is staggering—about $600 per ton, as opposed to $400 per ton for seed shipped and $200 for seed pushed across the border. At the same time about 5,000 tons are thought by now to have reached Cambodia by sea. What is not clear, however, is how much of this seed has been distributed through the countryside and, just as important, how much food has been distributed along with the seed. Seed distributed to hungry peasants will be eaten not planted.

How much food has been arriving in Cambodia and what is happening to it? The airport in Phnom Penh can handle only 7,000 tons a month. Phnom Penh harbor used to handle 20,000 tons a month, but this has been cut back by the collapse of one of the wharves in March. The only encouraging development has been the arrival of a large and expert team of Russian stevedores at the seaport of Kompong Som. This should raise the unloading capacity of the port above the low tonnage of 22,000 tons a month estimated by a World Food Program survey last April.

More difficult to solve is distribution from the ports into the countryside. This is done almost entirely by rail and road, when it is done at all. The train from Kompong Som to Phnom Penh, according to a detailed UNICEF report of May 1, carries only about 6,000 tons a month. UNICEF also says that “significant” amounts are taken by train from Phnom Penh to Battambang. But “the railway is hampered by a lack of locomotive and rolling stock in good repair as well as of operating experience.”

There are, according to UNICEF, about 1,500 trucks in Cambodia at the moment (500 from ICRC-UNICEF, 90 from Oxfam, 670 from various countries including those in the Warsaw Pact, and 230 old trucks patched together). Their total load capacity is about 9,000 tons, but more important is what UNICEF calls their “movement capacity”—whether they are being properly used or not. They are not.

UNICEF is being diplomatic when it reports that the “use of the trucks is not efficient.” In fact, one senior UNICEF official told me that the trucks are carrying only about 15,000 tons of food a month.

This is a terrifying figure. It means that each truck is making an average of about one and a half journeys a month. The rest of the time trucks are standing idle, awaiting repair, stalled by broken bridges and along smashed roads (almost no attempt has been made to repair the road network). Others are being used by corrupt local officials for trade in black market goods from Thailand, or by truck drivers themselves for carrying paying passengers rather than relief supplies. The aid agencies in Phnom Penh have even heard stories that some trucks in some provinces have actually been sold to black marketeers.

Advertisement

Together, then, trucks and trains appear to have been carrying little more than 20,000 tons of supplies a month out of the ports and into the country in recent weeks. Yet UNICEF reckons that 35,000 tons of food alone are needed.

Considerable amounts of food are now being distributed to government workers. Currency was reintroduced in April, and they are now allowed to buy 20 kilos of food each a month. There are thought to be at least 250,000 government employees; this means that at least 5,000 tons of food are being reserved for them every month—a large proportion of all the food available for distribution.

Random checks in the countryside suggest that in many places villagers are receiving as little as two kilos a month. UNICEF’s report acknowledges that “the bulk of the relief food available” has been distributed in Phnom Penh and to government officials. “It appears little so far has been distributed to the ordinary consumer, especially in rural areas where stocks might have been presumed to be available.”

The physical effects of such inequitable distribution are predictable. An Oxfam doctor, Nick Maurice, made a survey of children in five provinces at the beginning of May. The results, he reported, were “extremely alarming”: 26 percent of the children examined were suffering from malnutrition and 34 percent were borderline cases. He expected these figures to become worse as food distribution became even more difficult during the monsoon.

This situation must be treated with great seriousness and the utmost urgency. It is well known that chronic malnutrition in children leads to disease, stunting of growth and intellectual impairment…. During the examination of children, parents were asked whether they had been receiving food aid. There is a lot of evidence that people in rural areas are not receiving adequate amounts of food aid. Amounts received ranged from nil to 5 kg month and often the quality of food received makes it almost indigestible, eg maize which requires more than an hour of cooking. [Emphasis in original.]

This report alarmed Oxfam officials in Phnom Penh and also in Oxford itself. It came at a time when all relief officials in Phnom Penh were increasingly frustrated by the conditions imposed upon them by the Heng Samrin government. When the relief effort began in October Oxfam and some of the other agencies were reluctant to criticize the new regime, hoping that its young, inexperienced officials would become more willing to cooperate with Western relief agencies. That has not happened.

On the contrary, relief officials are now being given permission to leave Phnom Penh much more rarely than before. The reports of food distribution that the government originally promised both Oxfam and ICRC-UNICEF have often not been produced at all and have sometimes been useless. By the middle of April World Food Program officials had been told about the distribution of only about 40,000 of the 70,000 odd tons landed since October. They had been able to check even less.

Meanwhile ideological controls have tightened in Phnom Penh. This has coincided with the eclipse of the regime’s nominal leader, Heng Samrin, and the emergence of the communist party secretary, Penn Sovann, as the dominant figure. Penn Sovann is thought to be a more doctrinaire bureaucrat than the ineffectual Heng Samrin. Interpreters with whom aid officials had become friendly have been removed. (Oxfam’s favorite interpreter was packed off to the embassy in East Berlin.) New interpreters are much less helpful; they have been ordered not to “fraternize.” Accusations of “fraternization” have been reported and discussed right up to the ministerial level. Recently a complaint was made to a minister that an Oxfam driver had driven team members around Phnom Penh to “flirt” with girls.

Restrictions on the size of the teams of relief workers sent to Phnom Penh have not been lifted—the ICRC-UNICEF team has about twenty-seven people; in Bangladesh ICRC had 140 with 300 local employees—and visas in and out of the country have become more difficult to obtain. UNICEF officials in Phnom Penh have even been warned that perhaps only Soviet and East European citizens will be allowed to work for UNICEF in Cambodia in the future.

At the same time Cambodian officials are having to spend more time on political education. The director of Medical and Child Health was recently required to spend seven weeks on a goodwill mission to East Berlin, Moscow, and Hanoi. The entire staff of the Ministry of Health was sent to Laos for a two-week solidarity meeting. In fact the Ministry of Health is one of the weakest organizations in the country, and outside Phnom Penh medical care is almost nonexistent.

The government has made much of its claim that the Khmer Rouge killed all but fifty of the country’s doctors, but until recently it refused to allow in foreign medical teams. Only in February was the International Red Cross able to bring in about thirty Soviet and East European medics. Some Cuban and Vietnamese medical people have arrived and recently a Swedish team was given permission. But the number of medical workers is still only around 200—hardly adequate for a population of five million who have suffered ten years of terrible deprivation. Even doctors from Eastern Europe say privately they are deeply depressed by the restrictions that have been imposed.

On Monday, May 19, a group of relief teams in Phnom Penh sent a strong letter of protest to the government in Phnom Penh. The Red Cross and UNICEF followed this on May 23 with an appeal to both Western governments and the Vietnamese and Phnom Penh authorities. It asked the Western nations for more money, especially to improve the transport system. And it asked Phnom Penh for an assurance that relief be “equitably distributed among the whole civilian population in need.” The statement concluded with what seemed like an ultimatum:

Without such an assurance it cannot be expected that sufficient resources will be entrusted to the responsible organizations. Nor in the prevailing circumstances should the organizations themselves be expected to continue their humanitarian work.

This was the situation in which the meeting in Geneva took place. The impetus for it came from the ASEAN countries, particularly Thailand, pushed by the United States. Kurt Waldheim agreed reluctantly only after an ASEAN resolution calling for a meeting was passed by the Economic and Social Council of the UN at the beginning of May. Waldheim was reluctant partly because of his feeling, shared by Donald McHenry, the US Ambassador to the UN, that Indochina has been getting disproportionate attention relative to other disasters such as the refugee crisis in Somalia, where hundreds of thousands of people are in danger of starvation. (An Oxfam doctor who visited Cambodia last fall and Somali refugee camps in April reports that conditions in Somalia are worse than in Cambodia.)

ASEAN asked the French and then the British foriegn minister to act as chairman of the conference. They refused; so did all other members of the European Community. American officials claimed privately that the Europeans were frightened of offending the Russians. In the end, Andrew Peacock, foreign minister of Australia, was chosen as chairman.

The Vietnamese and Heng Samrin governments acknowledged the conference only by sending delegates from their Red Cross organizations to Geneva, though not to the meeting itself. The Russians sent observers who entered by a side door and sat in the public gallery. The American delegation, led by Warren Christopher, was remarkable for including Frances Fitzgerald, author of Fire in the Lake. Times have indeed changed for such an influential critic of US policy in Vietnam to represent the US at a conference much concerned with the behavior of the Vietnamese.

Christopher promised $29 million in addition to the $85 million the US has already given or pledged. He made a hard-line anti-Soviet speech into which he dragged Russian policy in Cuba, Afghanistan, and the Horn of Africa, in case anyone needed reminding of the international political considerations which haunt any discussion of Cambodia. (He also seized a pause in his own press conference as an excuse to walk out rather than face what he apparently thought would be hostile questions about the US relationship with the Khmer Rouge.)

Most speakers formally praised the international aid organizations. In the corridors comment was less kind. No one had a good word to say for the Food and Agriculture Organization, whose incompetence seems to have cost the relief effort millions of scarce dollars. Not only did its tardiness make necessary an airlift of seed, but it has been paying $100 a ton more than the voluntary agencies for rice seed on the Bangkok market. At the same time there is now almost open warfare between American government officials and James Grant, the Director General of UNICEF. Mr. Grant was a senior AID official in Vietnam during the Sixties. At that time he was optimistic about the government in Saigon; recently he has tended to be optimistic about the one in Hanoi. He was anxious to cut down the Thai border operations, as the Phnom Penh regime wants, and he spoke about the “seed saturation” of Cambodia. This was a notion which the American and other delegations firmly and convincingly dismissed. Border seed distribution will continue.

Altogether the conference produced pledges of $116 million toward the $180 million that is needed for the rest of 1980. It urged the Phnom Penh authorities to allow more aid workers and more doctors into Cambodia, to permit the use of provincial airports, and to open direct supply routes from Vietnam and Thailand.* At the end a UNICEF spokesman said that the Phnom Penh authorities had agreed to allow direct flights from Bangkok and had asked the USSR to stage internal flights to provincial airports. He promised that more trucks were coming from UNICEF, Oxfam, Japan, and East Germany. He announced that the Swedish medical team had been given permission to go to Phnom Penh, that Vietnam had agreed to the use of the port of Vung Tau to receive aid. All in all, UNICEF seemed optimistic.

The president of the International Red Cross was much less sanguine: the failures of the Cambodian authorities to allow effective distribution have been too many and too discouraging. And so far UNICEF’s optimism has not been justified. On May 29 the government in Phnom Penh issued a statement denouncing the Geneva conference as “a gross interference in the internal affairs of Kampuchea. Any resolution or motion concerning Kampuchea will be considered null and void.”

And so the wretchedness continues. The Vietnamese have recently repeated their claim that the situation in Cambodia is “irreversible.” The Chinese still insist they will support the Khmer Rouge and other resistance to Vietnam indefinitely. There is some sign that the Thais are now less inclined to allow Peking to continue to arm the Khmer Rouge through Thailand. But soon the Khmer Rouge may well be self-supporting within Cambodia. The policy of the Western nations remains one of approving or tolerating—although tacitly—the activities of the Khmer Rouge against the Cambodian regime, and seeing that they retain Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations when this issue is decided at the annual credentials committee in September. American officials acknowledge that this presents a “public relations problem” and profess “distaste” for the vote they cast last September to seat the Khmer Rouge. Mr. Thioun Moeum, the Khmer Rouge ambassador, expressed his gratitude to me for the recognition the West is giving his organization.

Cambodia is a political disaster. A solution in the form of compromise could be contrived by politicians. It is not happening. The Vietnamese appear both indifferent to the crisis over aid and immovable; Western governments say they are opposed to the mass murderers of the previous regime but help to underwrite their war. Of the ghastly failures that have taken place, not least has been the failure of political imagination.

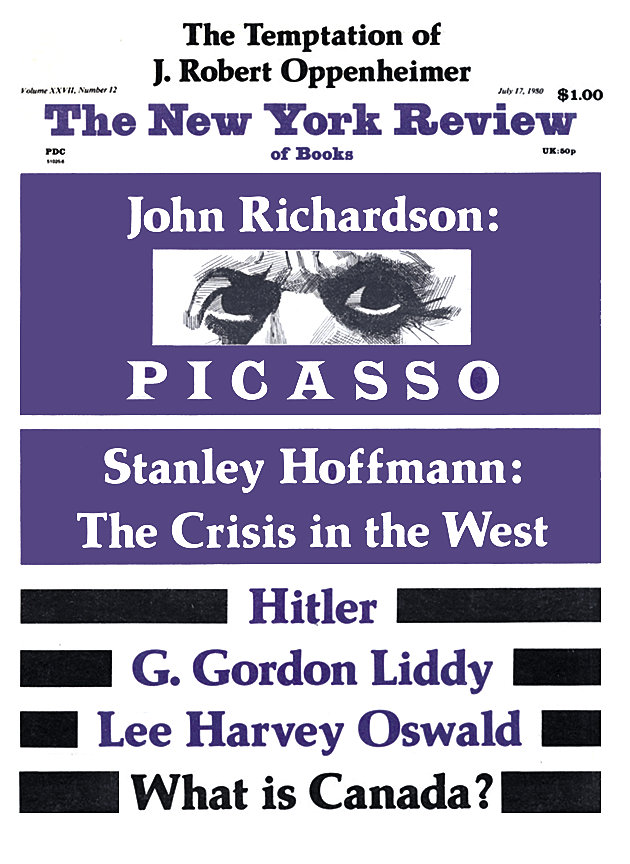

This Issue

July 17, 1980

-

*

By consistently refusing to allow a direct land route to be opened up from Thailand into Cambodia, the Vietnamese have—ironically—done much to help the Khmer Rouge to rebuild their forces. The Khmer Rouge have easily captured supplies from the hundreds of thousands of peasants who have traveled to and from the Thai border over the unofficial routes. A carefully controlled supply system along road and rail would have made it much more difficult for them to take supplies from the peasants. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, now in North Korea, believes that the Vietnamese want the Khmer Rouge to survive—because their presence, more than anything else, can justify continued Vietnamese occupation. ↩