Judas Roquín told me this story, on the veranda of his mildewed house in Cahuita. Years have passed and I may have altered some details. I cannot be sure.

In 1933, the young Brazilian poet Baltasar Melo published a book of poems, Brasil Encarnado, which stirred up such an outrage that Melo, fore-warned by powerful friends, chose to flee the country. The poems were extravagant, unbridled even, in their manner, and applied a running sexual metaphor to Brazilian life; but it was one section, “Perversions,” in which Melo characterized three prominent public figures as sexual grotesques, that made his exile inevitable. Friends hid him until he could board a freighter from Recife, under cover of darkness and an assumed name, bound for Panama. With the ample royalties from his book, he was able to buy an estancia on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, not far from where Roquín lived. The two of them met inevitably, though they did not exactly become friends.

Already vain and arrogant by nature, Melo became insufferable with success and the additional aura of notorious exile. He used his fame mainly to entice women with literary pretensions, some of them the wives of high officials. In Brazil, however, he remained something of a luminary to the young, and his flight added a certain allure to his reputation, to such a point that two young Bahian poets who worked as reporters on the newspaper Folha da Tarde took a leave of absence to interview him in his chosen exile. They traveled to Costa Rica mostly by bus, taking over a month to reach San José, the capital. Melo’s retreat was a further day’s journey, and they had to cover the last eleven kilometers on foot. Arriving at evening, they announced themselves to the housekeeper. Melo, already half-drunk, was upstairs, entertaining the daughter of a campesino, who countenanced the liaison for the sake of his fields. Melo, unfortunately, chose to be outraged, and shouted, in a voice loud enough for the waiting poets to hear, “Tell those compatriots of mine that Brazil kept my poems and rejected me. Poetic justice demands that they return home and wait there for my next book.” For the two frustrated pilgrims, the journey back to Bahia was nothing short of nightmare.

The following autumn, a letter arrived in Cahuita for Baltasar Melo from a young Bahian girl, Amada da Bonavista, confessing shyly that her reading of Brasil Encarnado had altered her resolve to enter a convent, and asking for the poet’s guidance. Flattered, titillated, he answered with a letter full of suggestive warmth. In response to a further letter from her, he made so bold as to ask for her likeness, and received in return the photograph of an irresistible beauty. Over the course of a whole year, their correspondence grew increasingly more erotic until, on impulse, Melo had his agent send her a steamship ticket from Bahia to Panama, where he proposed to meet her. Time passed, trying his patience; and then a letter arrived, addressed in an unfamiliar hand, from an aunt of Amada’s. She had contracted meningitis, and was in a critical condition. Not long after, the campesino’s daughter brought another envelope with a Bahia postmark. It contained the steamship ticket, and a newspaper clipping announcing Amada’s death.

We do not know if the two poets relished their intricate revenge, for they remain nameless, forgotten. But although it would be hard nowadays to track down an available copy of Brasil Encarnado, Baltasar Melo’s name crops up in most standard anthologies of modern Brazilian poetry, represented always by the single celebrated poem, “In Memoriam: Amada,” which Brazilian schoolchildren still learn by heart. I translate, inadequately of course, the first few lines:

Body forever in bloom,

you are the only one

who never did decay

go gray, wrinkle, and die

as all warm others do.

My life, as it wears away

owes all its light to you…

When Judas had finished, I of course asked him the inevitable question: Did Baltasar Melo ever find out? Did someone tell him? Roquín got up suddenly from the hammock he was sprawled in, and looked out to the white edge of surf, just visible under the rising moon. “Ask me another time,” he said. “I haven’t decided yet.”

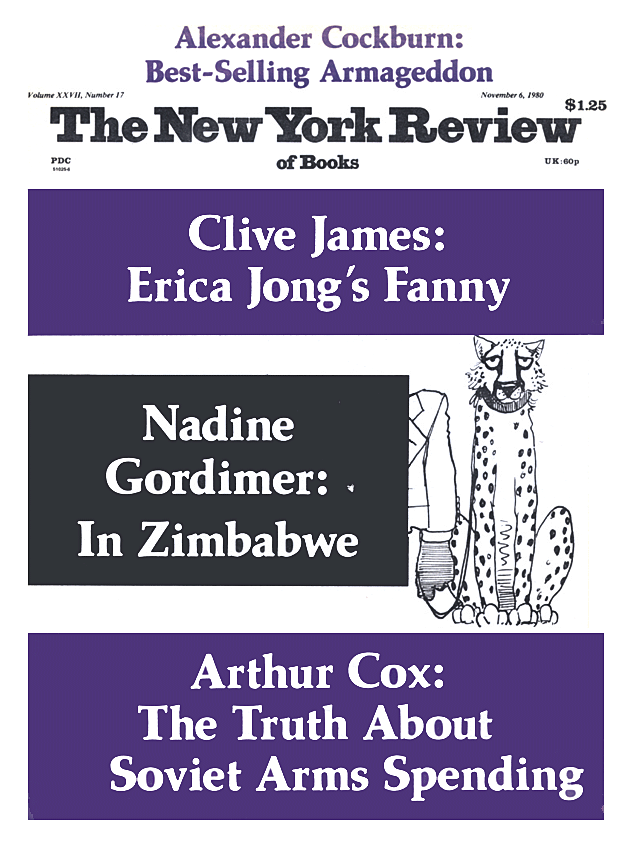

This Issue

November 6, 1980