In response to:

The Heroic Hermaphrodite from the October 9, 1980 issue

To the Editors:

Frederick Brown’s sensitive review of Hercule Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite [NYR, October 9] rightly contrasts the literary representation of the hermaphrodite with the pathos of a real one. I wonder that it was not pointed out that Hercule Barbin almost certainly had a disorder which has recently become understood on a biochemical basis, namely deficiency of the enzyme 5 alpha reductase. * This enzyme converts the male hormone testosterone to another hormone, dihydrotestosterone, abbreviated DHT. Some tissues require DHT to become masculinized while others do not. Hence, persons with this deficiency are a mixture of male and female anatomical features. It is unique among disorders of physical sexual development in that the affected individual changes psychological gender orientation at puberty. Case reports of this disorder are the only real evidence in humans that hormones rather than environment influence a person’s concept of what sex he or she is.

Advocates of nurture over nature have argued, in essence, that such individuals switch to a male identification at puberty because the male’s social position is preferable. The case of Hercule Barbin suggests the contrary, that Hercule left an environment which was protective and which did not restrain her from sexual contact with women for one that was much less satisfactory. Hercule seems to have insisted on taking a man’s identity simply because she felt that her correct gender was male even though leaving the convent changed her life considerably for the worse.

Hermaphrodites in art and literature possess in some degree the attractions of both sexes. Real hermaphrodites are deprived of sexuality because there is no role in society available for a person who does not belong by virtual physical development to one or the other sex. Fortunately, it is now possible to correct such disorders in infancy so that the individual can be wholly male or female.

Geoffrey P. Redmond, M.D.

University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont

Frederick Brown replies:

Alexina does indeed answer the description of hermaphrodites who suffer from an enzyme deficiency, but I am not sure that the text proves Dr. Redmond’s claim that “hormones rather than environment influence a person’s concept of what sex he or she is.” It seems to me that Alexina’s image of herself remained ambiguous even after puberty, which would lend credence to the observation made by John Money in “Human Hermaphroditism” that what often governs psychological gender identity with hermaphrodites is the sex parents assign them before the age of three. Did Alexina’s parents waver? The text is silent on this score, though Herculine would appear to be rather a masculine choice of name for a female infant. Changing it to Hercule, as Dr. Redmond consistently does, resolves an issue that may never have been resolved in Herculine’s mind or in her parents’. It should also be noted that when Herculine-Alexina left the boarding school (not convent) for Paris, her journey was undertaken in a spirit of high adventure rather than with foreknowledge of calamity. “That vast desire for the unknown made me egoistic and prevented me from regretting the very dear ties that I was going to break of my own free will.” Not only Dr. Redmond, but Michel Foucault as well ignores this last statement in depicting Alexina as the heroic victim of a civilization that imposes artificial structures upon the naturally indeterminate, or innocent, being. It was not a protective environment she fled, or if it was, it did not protect her from her own inner conflict. What Foucault calls “the happy limbo of a non-identity” has much more to do with Foucault than with Alexina, who loved limbo mainly in retrospect.

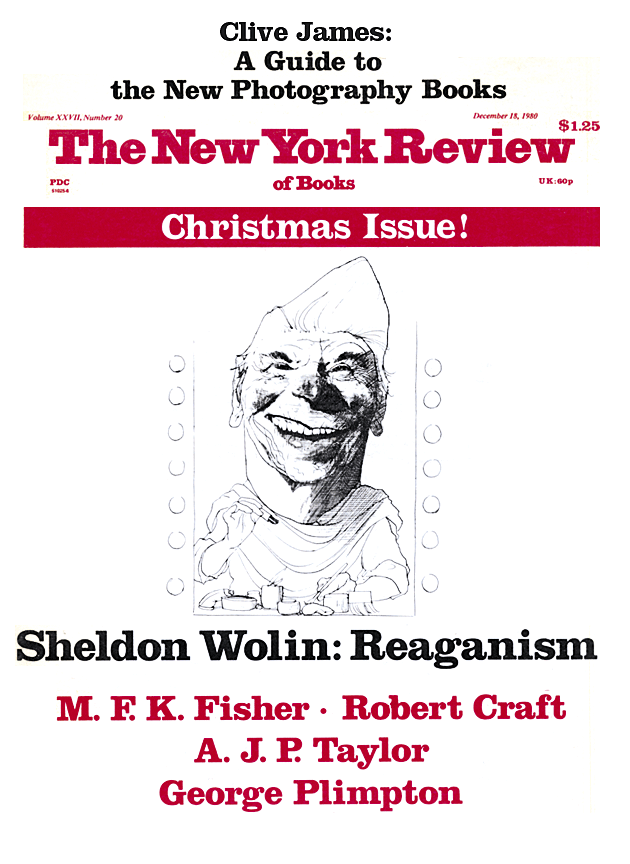

This Issue

December 18, 1980

-

*

J. Imperato-McGinley, R.E. Peterson, T. Gautier, et al., “Androgens and the Evolution of Male Gender-Identity Among Male Pseudohermaphrodites with 5 alpha reductase deficiency,” New England Journal of Medicine 300:1233-1237, 1980. ↩