For Israelis, one of the most disturbing facts of life is that so many of the five hundred thousand Arabs who are Israeli citizens are increasingly militant supporters of the PLO. In the elections of 1977 over half of them voted for Rakah, Israel’s pro-Moscow Communist Party, which claims to be anti-Zionist and openly favors a PLO state in occupied territory. When the party planned an Israeli-Arab political congress in Nazareth for December 6 the Begin government banned it from taking place. Arab student organizations at the Hebrew University and other universities have refused to stand guard duty on their own campuses, though these have been the targets of terrorist attacks. Students’ groups have issued statements endorsing the PLO as the sole representative of the Palestinian people. So has Tufik Zayat, the communist mayor of Nazareth, who told me not long ago that such sentiments are only the surface signs of deep disaffection.

Four books have been published recently to account for the estrangement of “Israeli” Arabs from their state. Each seems complementary to the others, which is remarkable in view of the diverse origins of their authors. Elia Zureik is a Palestinian scholar who lived in Israel until he graduated from high school and was thereafter educated in England. His book is the most bitterly polemical of the four, but also the most daring work of social theory. The Palestinians in Israel recapitulates the relations of Jews and Arabs in Mandate Palestine in order to show that the Arabs are casualties of Zionism’s “internal colonialism.”

Zureik’s main evidence for this thesis is the current social condition of his former community. About half of Israel’s Arabs still live in nearly isolated towns, and serve as a work force for Israeli Jewish industries. A quarter work on Jewish farms and construction sites. Zureik’s figures convincingly show that the Israeli Arabs are “dependent upon and dominated by” the Jewish economy; that Arabs have become a segregated industrial proletariat in Israel and will remain one unless some of Israel’s political institutions are reformed. The other books under review recognize the force of Zureik’s facts.

But Zureik’s attempt to use the Arabs’ current problems to discredit Zionism under the British Mandate as colonialism is something else. It seems to me not only insupportable from the historical record, but to obscure the intense cultural conflicts among the Israeli Arabs themselves. In 1948 the 175,000 Palestinian Arabs who stayed in the territory that became Israel were almost all peasant farmers. Unlike the professional people, merchants, workers, and other urban Arabs who fled cities such as Haifa and Jaffa in panic, or were driven out of towns such as Ramle by the Haganah, the Palestinians who became Israeli citizens lived mainly in rural villages in north-central Galilee or the Little Triangle between Haifa and Nablus where the fighting did not quite reach. With the exception of Christian Nazareth, these were among the most backward places in the country that became Israel.

Zureik knows this, but he refuses to acknowledge that the changes in the social conditions of the Arabs in these regions are more usefully considered for the period after 1948 rather than for the one before. He does not want to write about these Israeli Arabs apart from the Palestinian nation as a whole. He does not consider that the flight of urban Palestinians in 1948 could be understood as a consequence of sudden war—but rather wants to portray it as the culmination of Zionist “colonialism” which presumably still exists. To prove his case against the state, Zureik tries to show not only that Israel’s Arabs have been “proletarianized” since 1948—this, after all, might suggest that they made some advance—but also that their leading commercial classes have suffered as Jewish commerce gained. To do so, he cites evidence to show how, in 1944, about 11 percent of the Arab population was employed in “commerce and services,” as compared with only 8.2 percent in 1963. What Zureik omits to say—at least here—is that most of the urban Arabs who had commercial jobs fled in 1948. Nor does he recall that a great many working in “services” in 1944 were clerks in the Mandate bureaucracy. By contrast, the number of Arabs working as “traders, [commercial] agents, and salesmen” in Israel, according to his own statistics, actually doubled from 1963 to 1972 and was roughly equal to the proportion of Jews doing the same work during the same years.

Not that such comparisons could anyway tell us much about political power in Israeli society. In 1972 most powerful Israeli corporations, collectives, and unions were largely ruled by an old-boy network of Histadrut managers and Labor Alignment politicians, few of them Sephardic Jews, or sympathetic to them, let alone Arabs. The crucial disparity between Arabs and Jews was this: nearly 40 percent of Jews had technological, administrative, and clerical jobs in 1972—most of them not in private commerce—and only 6.7 percent were unskilled laborers. But only 12 percent of Arab workers were employed in such privileged fields. To grasp the implications of such facts, which could have made a stronger case on behalf of the Israeli Arabs, Zureik would have had to undertake a much closer analysis of Israel’s complex political economy; and he would have had to raise the question of the resistance of rural Palestinians to modernization.

Advertisement

Sami Mar’i is prepared to do both, which does not make his book less challenging to those who would wish Israel well. Mar’i was, like Zureik, born and educated in Israel, but he attended the Hebrew University and finally decided to stay. He is currently one of a handful of Arabs teaching social science at Haifa University, the only university in Israel to admit a substantial number (over a thousand) of Arab students. Few writers are in a better position to survey the dilemmas of Israel’s Arab citizens, and few have done so more persuasively.

Mar’i’s main subject is the education of Arabs in Israel, and this leads him to consider the larger situation which determines the personal and political attitudes of Arab students. His central point is plain: Arab citizens will have to have far greater social and economic opportunities in Israel if their children are to feel loyal to the state, and their teachers are not to feel like quislings. Mar’i believes that the Arab educational system ought to be run by Arab educators, that it should teach more about Palestinian national culture and history. He leaves open the question whether cultivating Palestinian identity will inevitably lead to anti-Zionism by calling for an “Arab national identity which is not and should not be anti-Jewish.” If this seems evasive, it is typical of a book that is devastating in its facts, yet concerned to promote conciliation between Israeli Jews and Arabs.

Mar’i also makes clear what Zureik had implicitly denied: that most of Israel’s Arabs regard the Jewish majority and Hebrew culture with some ambivalence. While Israel to them is conquering, humiliating, and hostile, it has also been a source of rapid progress for some Arabs in their knowledge of technology, and their sense of women’s rights, economic liberty, and the values of individualism. Much that they want to know about the modern world is written in Hebrew.

But of course any such guilty feelings of admiration for Israelis do not outweigh their contempt for the state. Israel’s Arabs have had bitter claims against their government, arising out of the years of bloody conflict during and after the founding of the Zionist state. Quite apart from the antipathy Palestinian peasants felt to Zionism, and to Jewish soldiers, the state took actions immediately after the 1948 war that were bound to cause deep anger among its Arab citizens. Instead of democratic elections, military government was imposed on the Arab towns and this was only withdrawn in 1966 under the liberal regime of Levi Eshkol. Between 1949 and 1956, moreover, the state expropriated about half of all Arab land for Jewish settlement, often resorting to specious claims that this land was abandoned or was required for state security. In mitigation of this record, officials point out that Israel was vulnerable to the raids of Palestinian fedayin throughout this period, and was frantically settling hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees from Arab countries. But Israel’s Arabs bore the brunt of this turmoil for a generation and do not forget the violence done them by Israeli forces.

For example, during the Sinai war in 1956, forty-three people, including some women and children, were summarily executed for breaking the curfew at Kfar Kassem. The Israeli commanders were court-marshaled, and later pardoned. In 1976, six young men were killed by soldiers during demonstrations against new Israeli plans to expropriate land in the Galilee. The government would not hold public inquiries into these killings. Mar’i shows in detail, moreover, that in addition to expropriating land state officials discriminated against Arab municipalities and public schools during this period, denying Arabs the funds that might have helped them catch up to standards in the Jewish sector. He is particularly hard on the record of the state’s “Arab Department,” which reports directly to the prime minister and the Defense Ministry but claims to be a bureaucracy set up to serve the Arab community.

Mar’i’s book is poignant because he senses the contradictory situation in which young Arabs find themselves. Whatever their current enthusiasm for the “Palestinian cause,” Arab students, he writes, became part of a modern society in Israel. They have ceased viewing membership in a powerful, patriarchal clan as central to their lives and have grown accustomed to coeducational arrangements outside school as well as within it. Compared with children in West Bank schools, Israeli Arab children became impatient with rote learning and have shown, according to research Mar’i cites, a much higher predisposition for independent and “creative” thinking.

Advertisement

And Mar’i reminds us that these students have absorbed such tendencies in Hebrew. During four years in high school, Arab students have to study 768 hours of Hebrew language and literature (including Bialik, Alterman, and leading Zionist writers), as compared with only 732 in Arab studies. Yet these students don’t unequivocally despise the culture they have had to master. It seems no exaggeration to call them “Israelis” even though the standard dogmas of both the Arabs and the Israeli Jews would deny that this is what they are. Still, Mar’i’s most discouraging finding is that 90 percent of the Arab students he interviewed in 1977 doubted they had a future in Israel. Some 40 percent of young Israeli Jews concurred with this assessment of Arab prospects.

Such attitudes might change if progress can be made on peace between Israelis and the Palestinians beyond Israel’s borders. But another finding shows the severe obstacles that would exist for Israeli Arabs even if peace should become possible. Arab high school seniors who major in science believe their future in Israel will be especially grim; and some 90 percent choose to major in the humanities. At first this seems odd: the students, as Mar’i found, consider the humanities curriculum in Arab schools degrading with its heavy load of Hebrew culture. Besides, one would expect the young members of a minority to advance most rapidly in technical jobs where knowledge of mathematics and science would count for more than the loyalties of the majority. To explain their reaction, Mar’i takes us back to Zureik’s claim: that Israeli Arabs lack the independent industrial base which could absorb their young scientists and professionals. The Jewish managers of Israel’s advanced industries will not hire Arabs, whether because of misplaced feelings of patriotism, fear of espionage, or common racism.

Moreover, technical schools are very expensive to develop. Arab municipalities which carry little weight with Israeli political leaders, and have a small taxbase, cannot afford them, even though a majority of Arab parents, albeit a small one, favor technical training for their children. Mar’i’s conclusion, that students choose the humanities because they’ve grown resigned to a career in school-teaching within their own towns, seems inescapable. Arab students expect, and accurately, that they will be excluded from respectable positions in Israel’s urban economy. Recent promises by Begin’s adviser on Arab affairs, Benyamin Gur-Arye, that about $30,000 of Moslem trusteeship (wagf) funds would go to gifted students and that school overcrowding will be eased over the next ten years seem unlikely to change their minds.

To understand their social frustration, one can usefully turn to Ian Lustick’s book. A professor of government at Dartmouth, Lustick seeks to show how Arab dissatisfaction derives from the basic pattern of the Israeli political economy. He first analyzes the various methods by which Israel’s Labor bureaucracy and the state’s Arab Department have broken up the Arab community by encouraging the preeminence of local hamulas. To that end, Israeli leaders have made separate and unequal arrangements with the Druze communities and resorted to high-handed “security regulations” to suppress the emergence of any national Arab party—like the El-Ard (“the Land”) Party of the early Sixties—which might field candidates for election to the Knesset.

The historical inability of Israeli Arabs to organize on a national scale interests Lustick most. Israeli Arab workers are not only subject to repression by the government; they must also depend on the quasi-socialist and private industries run by Jews for their livelihoods. During the 1960s and 1970s, the established political parties gave small numbers of the most promising young Arabs jobs in the government and the Histadrut where they would have to be politically circumspect. But such sinecures have run out. That the Rakah Party receives an independent subsidy from Moscow has thus helped to make it a singularly effective forum for Arab dissidents who would otherwise have no sympathy for communist social theory. But Lustick points out that Rakah’s Jewish leaders, such as the old Stalinist Meir Wilner, have exercised subtle constraints on Arab dissidents, keeping the Rakah members tied to the communists’ binationalist program.

Lustick’s most pointed argument is that Israeli citizenship is of no advantage to Arabs who want to live in Israel so long as the governing apparatus will not reapportion the power held by the semi-official Zionist institutions established during the years of immigration before the state. These bureaucracies—the Jewish Agency, the Jewish National Fund, the organized Rabbinate—routinely violate the democratic standards which must be upheld for the Arabs if they are to gain anything like equality.

The problem Lustick shrewdly identifies is not that Israel is a Zionist state. It is, rather, a democratic state which accords some important civil rights to all, but in which the old Zionist institutions still reserve the principal economic benefits only for the Jews. The Jewish Agency has, for example, spent some five billion dollars to develop the Jewish economy and advance the prospects of Jewish families since 1948, resources to which no Arabs can have had access. Land expropriated from Arabs by the Israeli land authority for “public use” is casually consigned to the Jewish National Fund in order to, say, “Judaize the Galilee.” According to that fund’s regulations—once justified by Zionist officials as means of developing the Jewish economy independent of that of the Arab majority—this land may never be leased by non-Jews, even when no Jewish settlers will have it. Such regulations create hardship for Israeli Arabs in towns such as Nazareth and Acre that are critically short of housing.

Lustick’s criticisms of such policies imply that Israeli Arabs, if only they had the chance, would want to take an active part in the life of Israel while receiving a greater share of social benefits as they did so. But the growing separatist sentiment among Arab majorities in central and northern Galilee puts this in doubt. Lustick gives Israel moral credit for the democratic standards it has achieved despite the hostile feelings of Arab communities, and for the state’s traditional refusal to draft Arab men into the Israeli defense forces to fight other Arabs. But he points out that Israeli Arab youths have paid a high added cost for their exemptions, since national service is not only the prerequisite for being socially accepted in Israeli cities, but is also necessary for benefits upon discharge such as low interest mortgages, jobs which require security clearance, and so on.

Lustick’s excellent book has some flaws. His data are often taken from the 1950s and 1960s, and the lives of Israeli Arabs now seem both better and worse than his book anticipated. Better, because the Israeli economy has been liberalized during the last several years and shaken by inflation. Like many Sephardic families in petty commerce or on Moshavim, Arab merchants, contractors, drivers, and farmers have prospered by comparison with most other Israeli wage earners during this time. Yet, like members of kibbutzim, Arab workers who live a semi-rural life have been insulated from the disastrous inflation affecting Jewish workers in Israel’s large cities. The Arab birth rate is now almost twice that of Israeli Jews and is unlikely to decline in such rural areas as it might in the cities. While tens of thousands of Israeli Jews are emigrating, few Israeli Arabs feel they must.

On the other hand, since the Begin government’s election the political climate has become much worse for Israeli Arabs. The Arab Department no longer operates under the comparatively benign regime of Labor appointees such as Shmuel Toledano. Rather, the infamous Koenig Report calling for systematic impoverishment of Arab municipalities—secretly prepared during Rabin’s term by an Interior Ministry official and then put aside—now seems official policy. Tufik Zayat has charged, for example, that the Arab part of Nazareth now gets less per capita than one third of the revenues going to Jewish Nazareth. Lustick shows that the Green Patrols, under the influence of Agricultural Minister Ariel Sharon, have been harassing Negev Bedouins whose lands are being expropriated for new air bases. And Sharon has for years openly threatened Israeli Arabs with expulsion if they show themselves hostile to his view of Israel’s interests.*

Not that Sharon speaks for most Israelis, or that his threats have intimidated Israeli Arab leaders. In fact, the latter now seem much less susceptible to the “cooptation, segmentation, and economic dependence” for which Lustick has tried to account. Rakah, led by such men as Tufik Zayat, seems to be emerging as the Arab national party Lustick could not find when he began his study. Mar’i’s view seems to me more nearly right, that circumstances have forced more and more Israeli Arabs to decide between, on the one hand, the PLO and, on the other, their fading prospects for combining cultural autonomy and integration into economic and civil life under the Likud regime. Should the Labor Alignment regain power in the forthcoming Israeli elections, the new ministers will have to act quickly to shore up those prospects and to engage the cooperation of young Arab activists and intellectuals in and out of Rakah, however this may rankle Labor’s old guard, especially from the Moshav movement.

It is to the reasons why such efforts are necessary that Yoella Har-Shefi devotes her new book. She uses the form of a historical novel to describe her own relations with a well-known Arab family whose identity she conceals but which most well-informed Israelis will immediately recognize. In doing so, she suggests the thinking of those Jews who are struggling for democratic treatment of Arabs. The narrator of her book often seems naïve, especially in her touching, crusading tone which brings to mind Gotthold Lessing’s hero in Nathan the Wise. She is justifiably hard on the Orthodox rabbis whose legal authority made it impossible for a son of the Arab family to marry his Jewish lover in Israel. Har-Shefi is a tough-minded journalist, a survivor of the death camps—I.F. Stone identifies her as an outspoken ten-year-old on the Haganah ship he wrote about in Underground to Palestine—and, like Stone, she has become a muckraker. She gained prominence by attacking the self-censorship of Israel’s dailies, which now do not give her steady work.

Her book is also a chronicle of the doubts common among Israeli liberals and secularists—e.g., A.B. Yehoshua or Amos Elon—who worry about condemning Jewish politicians while Palestinian leaders do not stop threatening their country’s survival. But Har-Shefi also harbors a more terrible fear: that Israeli Jews, so many of whom are from pre-modern Arab countries, may not have the will to bring off the Hebrew democratic revolution that European Zionists were once so confident would take place. Har-Shefi’s support for the Israeli Arabs therefore derives from an embattled sense of her own moral survival. Their success would be evidence that she is living in a free country.

(This is the second of two articles on recent books on the Palestinians.)

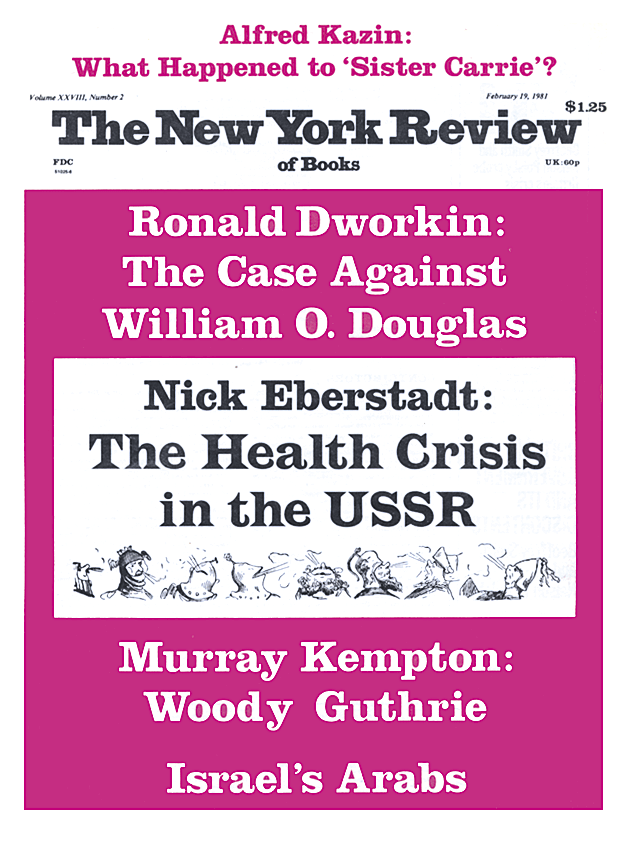

This Issue

February 19, 1981

-

*

See my report, NYR, May 31, 1979, and also Lesley Hazelton’s report, NYR, May 29, 1980. Ha’aretz, on December 4, 1980, reported that Sharon repeated his warning to Israeli Arabs during a speech at Kiryat Gat. ↩