—Haifa

As I write the battle in West Beirut is not yet finished. Will it end in a political settlement, or will the Israeli government really dare to order its army to enter the city and take it by force, with all the killing and destruction such a military operation entails, and all this in order to “terminate” the war Israel started?

And will this really be the end?

Only forty years ago we Jews returned to history as a substantial dynamic element, shaping our destiny with our own hands. No longer a passive entity to be borne on the waves of other peoples’ history, but a nation that acts and causes others to act, that directs its own destiny and so becomes part of the destiny of others, a nation like all other nations. But our entrance into history, which began secretly, stealthily, has acquired extraordinary force and intensity. Like an elderly student entering the university and applying to study in one year all the undergraduate courses, the Master’s courses, and even to start and possibly finish doctoral studies as well—so we are an ancient, passive people who stood in a corner and watched others make history; and then suddenly, for the last forty or fifty years, we have been vigorously cramming in great historical events that other nations spread out over hundreds of years of history: a struggle against a foreign power, a war of independence, total wars, the conquest of a foreign land, colonization, the dissolution of part of the empire, partial peace, and now another “little” war, begun perhaps in the manner of the proverbial nineteenth-century gunboat. And at every additional stage of this dizzying chronicle another force comes into view, an amazing vitality by which the nation reveals to itself and to the world, for better or for worse, qualities of whose existence it was not even aware.

The single rusty revolver of fifty years ago that was secretly passed from settlement to settlement for the purpose of defending the early pioneers has been transformed into one of the strongest armies in the world with thousands of tanks, a powerful air force, missiles and electronics and warships. We ourselves are amazed in every war to discover the extent of our power. There are serious people in Israel who attack those brave intellectuals who dissociate themselves from this war on the grounds that we intellectuals refuse to recognize that Israel really is strong and has the military and political power that establishes it as a prime factor in region, and as such must take upon itself duties and responsibilities in accordance with that great power. They claim that we really would prefer Israel to remain weak and edgy, capable perhaps of defending itself successfully, of fighting off an attack, but incapable of initiating far-reaching moves in order to try to establish a better order in the region, one that will be in accordance both with Israel’s interests and with moral values as Israel understands them. “The old image of the Jew is out, and you cannot adapt yourself to Israel’s new, realistic, down-to-earth image. You cannot acknowledge the next stage in Israel’s history.” There is certainly more than a grain of truth in this claim. There is also anxiety at realizing the magnitude of our strength: a reluctance to give up the warm and pleasant image of brave little David defending himself and to adapt to the new one, that of a big fat sheriff out to create order in the Wild West.

True, sometimes it is also necessary to play the part of the sheriff, but only on the condition that he is acting in the cause of law and justice and not in his own personal interests. A sheriff who is completely clear in his mind about the morality of his deeds is not evil, even if he is fat and sweaty. And here exactly lies the real root of argument—the connection between the Lebanese campaign and Israeli policy on the West Bank. There is no understanding one without the other.

At present the debate in Israel is much concerned with important questions, but not with the main ones. Did the government deceive when it initially declared a range of only forty kilometers? What was the true extent of civilian casualties? And what civilian casualties are permissible or not permissible? Even for the sake of a just cause? Can we really establish a new order in Lebanon and will it last? The crux of the argument is not in these questions, but in that great and endless debate—religious, Zionist, and Jewish—which erupted in our midst after the Six-Day War over the question of the “Greater Land of Israel.”

I have no doubt that even those opposed to this war are well aware of how much the people of Lebanon suffered from the lawless presence of PLO units in their midst, how intolerable life was there when the state disintegrated and in its ruins various factions engaged in a struggle of terror directed both inward and outward. True, the Lebanese problem did not start with the coming of the Palestinians and will not end even if the last Palestinian leaves. (Where to?) But one would have to be blind not to see the great relief felt by the people of Lebanon with the breaking of the PLO’s strength there.

Advertisement

Even those who strongly oppose this war are fully aware of the PLO’s tactics of refusal all through the years, policies that led the Palestinians, particularly during the last ten years, from one disaster to another. How much different and better their position would have been today if they had joined in Sadat’s initiative.

The anger of Israeli doves at the PLO is perhaps greater than that of the hawks. While the hawks see them as a pack of barking dogs preventing them from enjoying their territorial spoils, we doves believe that a just and fair solution is really possible for both the Palestinian and the Israeli people, and we find the suffering of the Palestinians heart-rending. We know that this suffering is caused not only by the Israeli government and the unworkable policies it offers the Palestinians, but also by the stubborn and unrealistic policies of the PLO.

But we also believe that man is not immutable, locked inside a national identity led by blind fate (Jewish, Arab, or any other), but a dynamic creature capable of changing and causing change. And so, despite our recognition of the terrible mistakes of the PLO, we still saw in it the germ of leadership. For their greatest problem (and indirectly ours as well) was that since the Thirties, when they began their struggle against us, it has been impossible for them to create a recognized leadership that is able not just to constantly say no, but also to agree on something constructive.

In recent years the PLO, for various reasons, has become the leadership of the Palestinian people. True, it is a bad leadership—visionary, stubborn, and at times corrupt, but it is a leadership that for historical reasons had found its footing and has proven in the last year—the year of the cease-fire in Lebanon that was accomplished with the agreement of Israel—its ability to impose its authority. (Not totally, there is no total authority over all the various and sundry Palestinian organizations; nor could Israel prevent a soldier from running amok in the middle of Jerusalem and firing on Temple Mount worshipers.)

This leadership should have been dealt with by military force, but also with reasonable and honorable proposals in order to exert pressure on it from both within and without to make it change its stand, to offer it a political solution that would respect Palestinian rights to self-determination: an alternative whose moral test would lie in the fact that we, as Israelis, would be able to say in all honesty that if we were in their shoes we would be prepared to accept this as a final compromise proposal.

However, this was not the road chosen by the Israeli government. Alongside the obituaries of fallen Israeli soldiers, alongside the long reports of events in Tyre and Sidon, there continuously appear advertisements for housing on the West Bank at extremely low prices in order to attract more and more Jews to that area, to continue that terrible project of implanting the substance of one people in the organism of another, like Siamese twins that will become one monster. (Even now, every third person in the Greater Land of Israel is a Palestinian.) Most American Jews who shout their enthusiastic support for Begin’s policy are not prepared to come and settle in the land of Israel, the land of their fathers whose rights they will zealously defend to the bitter end. Israel will slowly be forced to part with democracy as well, and to adopt some of the methods of the South African government in order to maintain this binational order. And the PLO, which will be uprooted from Beirut, will once more be divided into small terrorist groups that will contrive the metaphysical terror of the beginning of the next century.

And America lends its support to all this, not willingly, but in resignation, because it is swept along the stream of events and because of the neurotic relationship it has developed with Israel, in complete opposition to its long-range interests, in opposition to its basic values—as the US has already done many times during the last twenty years in Southeast Asia and South America. We doves sometimes feel that America in unwittingly becoming the enemy of a better, more moral Israel.

Advertisement

We are now at a dangerous crossroads. The war has already been fought, the dead have died, no one will bring them back to life. But is it possible to travel another road with new possibilities that have presented themselves? For these new possibilities are really there. Or perhaps what remains for us is only to shout again from the sidelines at the convoy galloping toward the next war.

—July 14

—translated by D. Nottman

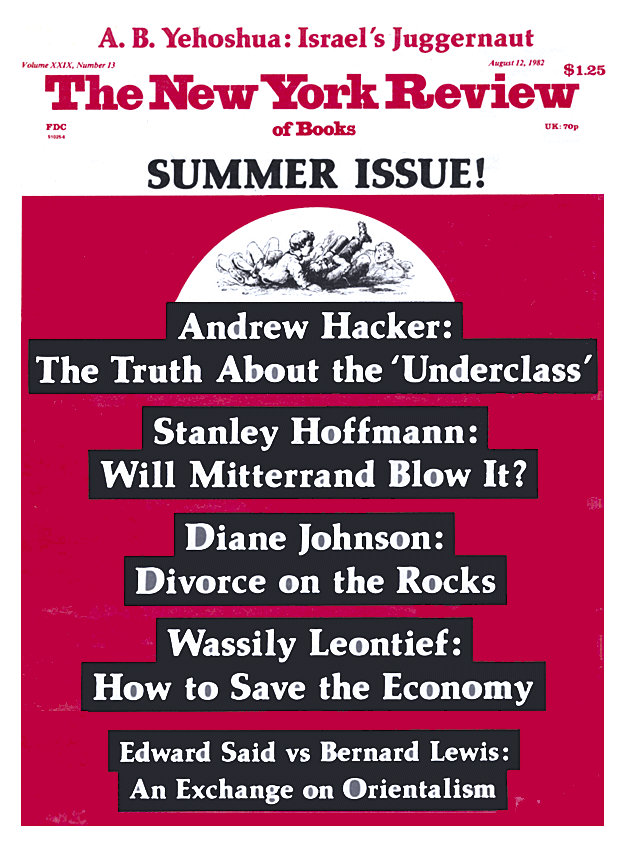

This Issue

August 12, 1982