In the First World War Western Europe was the main theater from first to last. Creat Britain and later the United States behaved as European powers, dispatching their troops to the western front much as France did. The first battle on the western front, the battle of the Marne, determined that the war would drag on for more than four years, with one battle after another, all more or less in the same place, all inconclusive. In August 1918 there began a final battle in which the German front crumbled though it never broke. The First World war ended for the British where it had began, British troops encountered German troops for the first time on August 23 1914 at Mons; Canadian troops liberated Mons a few hours before the armistice came into force on November 11, 1918.

Many people expected the Second World War to be much the same: a static Franco-German front stretching from Switzerland to the sea, with the British holding one segment of it. Quite the reverse. In May 1940 the French front collapsed after a few days of ineffective fighting with the British departing from the Continent at Dunkirk. For four years when much of the world was at war, Western Europe and particularly France was at peace, a peace no doubt made unpleasant by the presence of the German conqueror but peace all the same. When later I asked my French friends, “How did you get on in the war?” most of them answered, “For us the war ended in June 1940. The peace that followed was not all that bad.”

War returned to France or rather to a part of France only in June 1944 when the Allied armies of Great Britain and the United States landed in Normandy. Landings were a word of ill omen in British strategy: La Rochelle, Bel Ile, Walcheren, Gallipoli. This one brought success: the first successful seaborne invasion of France since Henry V’s time (the British produced a film on Henry V to go with the landing) and, John Keegah thinks, likely to be the last. Certainly the Normandy campaign was an astonishing achievement which is likely to remain unique. Great armies were ferried across the Channel, fully equipped to go into battle almost immediately after landing. These great armies were supplied by sea for over two months, better supplied even than the Germans were, thanks to the destruction of railways and bridges by the Allied air forces.

Moreover, the battle of Normandy not only led to the expulsion of the Germans from France. It marked the beginning of the end in all Western Europe for the German domination, despite pauses and occasional setbacks. Here was a paradox. In the First World War Western Europe experienced battle after battle for over four years, none of them decisive except the first and the last. In the Second World War Western Europe experienced only one great battle and it was decisive.

One can add many other distinctions that can be claimed for the battle of Normandy. It was probably the most successful of Allied battles. Allied cooperation reached its highest point, though it can hardly be said that General Bradley was an enthusiastic cooperator as long as he was under the command of General Montgomery. Keegan also points out rightly that this battle marked the highest point of action by parachutists, a force soon to be superseded by more effective means of airborne warfare. The battle was also strange in that the inhabitants were hardly involved, except when their habitations were battered to the ground as they were at Caen. John Keegan does what he can for the French by devoting his last chapter to a conflict far from Normandy, the battle for the liberation of Paris. Well, yes, there was a battle of sorts and, well, yes, the French Resistance hampered the German retreat across France, an action of great heroism but also of heavy and probably unnecessary losses.

Another of my French friends was, I suspect, more typical. He had a house on the coast not far from Coutances, itself not far from the front line. I asked him if the battle did not disturb him. He said only that no trains were running and that he had had to bicycle from Paris to the coast. Once there he spent his days sunbathing on the sands and swimming when the tide came up. One day someone ran down from the village to say that troops were passing through. My friend slipped a towel round his waist and ran up to the village. Some German troops marched through, accompanied by German tanks. There was then a break. Then there appeared American tanks and along with them American infantry. My friend removed the towel from his waist and waved it in the air. Then he returned to the beach. “And that,” said my friend, “is how I was liberated.”

Advertisement

The battle of Normandy provides splendid material for the contemporary historian. I’d say that more books have been written about it than about any other battle in history but I fear that can be said about many battles. At any rate there are plenty of books about it, some of them highly informative, some of them scholarly, some of them works of literature. The one I put highest is The Longest Day by the late Cornelius Ryan, one of the most gifted writers about battles I have known. Ryan carried the art of “I was there” sensation to its highest point. Of course he was not there but he created the feeling that he was. Keegan’s book has the same sort of presentation though it does not carry quite the same conviction.

Like many other writers, if not most, Keegan clearly wanted to write a book that was different. He has succeeded. Instead of presenting a battle between the Allied army and the German he has managed to conjure up six armies, all ingeniously arranged. The six are, I suppose, expected to display six different stories. You can almost hear the stage manager saying to each national contingent, “Be sure to play your national character for all it is worth.”

The results are sometimes a little surprising. The British contingent appear as “Yeomen of England.” Where on earth did the yeomen come from? Surely they went out with the longbow. Perhaps this is an unconscious recollection of Henry V and his longbowmen at Agincourt.

Often the distribution of national character enables John Keegan to slip in material remote from the battle of Normandy and its story. For instance, the appearance of a Polish division is an opportunity to evoke the Warsaw rising and its failure. As for the French, they played little part in the battle of Normandy. This was by no means their fault. It was the last product of Roosevelt’s obsessive dislike of De Gaulle, so great indeed that Roosevelt would have preferred France not to be liberated at all to the liberation’s being led by De Gaulle. It was not the least achievement of that remarkable man that the liberty march through Paris was led by General de Gaulle and not by some American general—Patton perhaps?

This book is not a narrative history of the Normandy campaign. It is a series of episodes, some connected, some not. In a prologue John Keegan tells us of his experiences as a schoolboy during the Second World War—good personal stuff. Then we have an exposition of how the Normandy campaign came into existence at all. The explanation is given quite rightly in terms of an Anglo-American argument: the Americans were for large-scale action at once, the British raised practical objections which postponed the Second Front, as it was called, until 1944. The belief is still widespread in the United States that the British never wanted the Second Front and had to be pushed into it. The British more sensibly saw the difficulties that had to be overcome.

It is a failure of Keegan’s book that it passes over the preparations: nothing about the laborious map work on the French coast, nothing about the preparations to transport two great armies and keep them supplied. The British and American fleets are virtually never mentioned except as literally “noises off”—great guns blasting the German positions from the sea. It is also a little strange that while the British and German commanders-in-chief, Montgomery and Rommel, make an appearance—Rommel more than Montgomery—no American commander other than Eisenhower, the supreme commander remote in England, gets a mention: nothing about Bradley, nothing about Patton until very late in the day. Maybe these omissions are a virtue. Maybe we have had too much about the generals and not enough about the fighting men. Nevertheless, to take all the news from the front line makes it difficult to find out what is happening. The result is a series of disconnected pictures.

First picture: drop of American parachutists—“All-American Screaming Eagles,” Keegan calls them—on the Cotentin peninsula. Very dramatic, very well done. Keegan brings out effectively the muddle and confusion that accompanied these drops, factors which soon put an end to paraforces as large-scale warriors. But where were the American infantry for whom the paratroopers were supposed to clear the way? Most of them were held up on Omaha Beach, a delay which nearly brought disaster to the American action and was then triumphantly overcome. This decisive combat receives no mention. Nor is there any mention of the British paratroop drop further along the coast, leaving the impression that paratroop war was an exclusive American invention.

Advertisement

Second picture: the landing of Canadian forces on what came to be called Juno Beach. The landing was a sensational success, giving the Allies a firm foothold on the Normandy shore. Here is the opportunity to contrast the success with the landing of Canadian forces at Dieppe two years previously—a landing which was a disastrous failure, a failing indeed so disastrous as nearly to rule out the possibility of any successful landing later. The Canadians carried the brunt of failure at Dieppe and were correspondingly inspired by the success at Juno Beach. Keegan makes much of the contrast but he does little to explain it. Dieppe taught a lesson as previous failures such as Gallipoli should have done: landings cannot be rushed, they must be prepared for a long time—two years in this case. But Keegan does not love planners or staff officers. The Canadians have one great advantage for Keegan: they really were a separate army and so help toward the title of the book.

Third picture: the Scottish drive south in an attempt to establish a corridor round Caen. Caen had been originally Montgomery’s objective for the first day. Actually he took much longer to get there. In his usual adroit way Montgomery made a virtue of necessity, making out that he was more concerned to keep the Germans occupied, whether in front of Caen or behind it, than to take the town. This left the Americans free to overrun the Cotentin peninsula and to take Cherbourg. Keegan sustains the Montgomery version by inserting the fall of Cherbourg in the middle of his chapter about the Scottish corridor. The Scottish drive was indisputably dramatic and we could have had more about the pipes and the kilts as the Scots went into action. One of my closest friends was second in command of this action so I heard much more of the drama than Keegan tells us.

Fourth picture: the drive south of Caen by the British army, miscalled the Yeomen of Englana, when Montgomery again set out to break the German front and again failed. This was the time when Bradley refused to cooperate with Montgomery and when many leaders, both British and American, urged Eisenhower to supersede Montgomery. In fact, Montgomery’s objective was fully achieved. The Germans could not resist the American pressure at St. Lô, and the way was clear for Patton to begin his sweep though Brittany and so on into the heart of France itself. In these circumstances it was somewhat ungrateful of Patton to lose patience with Montgomery’s delays and to ask permission to advance from the south where “we’ll drive the British into the sea for another Dunkirk.” I suppose this was meant to be funny.

At this point Keegan, as it were, goes over to the other side. Forgotten are the Americans and the British, forgotten the Scots and the Canadians. Keegan is drawn away into Eastern Europe where Hitler is very nearly blown up in the bomb plot of July 20. We get again the confusion in Berlin, the ruthless suppression by Hitler and his agents, the breach between Hitler and the army. The consequence on the Western front was the attempted breakthrough from Falaise by the German army, which was intended to reach the coast by way of Mortain and Avranches. This was a stroke of Hitler’s own and his obstinacy in continuing it brought the final defeat of the German army in Normandy. As the Germans passed through Mortain a gallant opposition was made against them by a Polish corps, which gives Keegan the opportunity to work in a reference to the fate of Warsaw. The gallant Polish action at Mortain provides the material for the most moving chapter in Keegan’s book.

Final picture: Keegan’s book describes the doings of five armies in Normandy: American, British, Canadian, Polish, and German. He is still one short and has to call in the French army as his reinforcement. But the French army took virtually no part in the Normandy campaign. Its first appearance in European action was during the liberation of Paris, when Leclerc’s force completed what the police and the Resistance had begun. The liberation is a story of high romance on both sides, French and German. It makes a dramatic ending to a book which conjures romance from some very hard fighting.

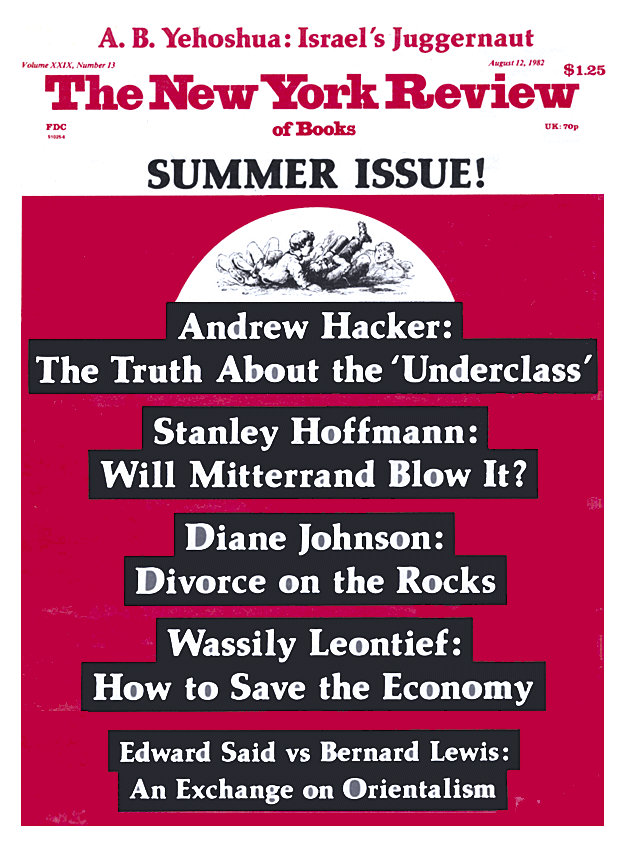

This Issue

August 12, 1982