In response to:

Is Locke the Key? from the June 10, 1982 issue

To the Editors:

Ian Hacking’s review of Hans Aarsleff’s collected essays [NYR, June 10] offers a generally fitting tribute to Aarsleff’s long-running effort to show that the study of language is an important aspect of intellectual history. But the review is weakened by what seems to me a misreading of Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

At the turning point of his review, Hacking doubts that Locke ever gave much thought to Adamism, the belief in an original language of nature which Adam spoke when he named the beasts of Eden. Hacking notes that Hobbes paid almost no heed to the language of Adam: he might have added that Bacon had already dismissed the subject as a matter for poets and theologians, urging other philosophers to ignore such magical schemes of language as that of Ramón Lull. Locke was, of course, the successor of Bacon and Hobbes and did not need to reopen the case for what would now be called motivated language. But he wrote about Adamism all the same.

For Locke had lived long enough to see that the universal language schemes of John Wilkins and the Baconians in the Royal Society never escaped the visions of Lull, and indeed returned to them at the urging of Seth Ward. Locke used the Adamists in his argument against the Atomists and their more reasoned efforts to show that language is innate, as Chomsky has contended in our day. The Adamic theme appears, not only in Book III (“Of Words”), but also in Book I (“Of Innate Ideas”). In his celebrated opening he echoes many of the Biblical quotations that Adamists used to support their claim that language was written in the heart by the finger of God. The effect is an exquisite irony, which Hacking seems to have missed in his otherwise judicious reading of Locke and Aarsleff.

Locke’s polemical use of Adamism is vital to Aarsleff’s own argument, for Aarsleff uses the same polemic when he comes to the motivated theories in nineteenth-century philology. The history of language study that emerges from Aarsleff’s essays is deeply ironic. What had been a radical challenge in seventeenth-century Adamism (forwarded by several of the reformers that Christopher Hill has brought to our attention) became a reactionary trend in the nineteenth century; what had been a conservative impulse (the anti-quarian study of Old English, for example) became a liberal movement with the rise of linguistic nationalism and relativism. Hacking is well aware that such conflicts are tied to larger intellectual patterns, as he has brilliantly shown in The Emergence of Probability, and that any effort to isolate philology from philosophy is doomed to failure. But he misses the aptness of Aarsleff’s polemic, having missed its origin in Locke.

The extent of Locke’s direct or indirect influence on German thought about language will remain a matter of debate. Perhaps Herder and Humbold had absorbed his themes well enough; perhaps their disciples were all too ignorant of these same arguments. In either case, Locke shored up a tradition in language theory that runs directly through James Campbell and I.A. Richards to contemporary rhetoricians like Edward P.J. Corbett, and indirectly through Condillac and Saussure to structuralists like Claude Lévi-Strauss. There have been conflicting versions of the same traditions, as Hacking notes, sufficiently so to warrant Aarsleff’s argumentative edge, for he certainly would not agree with the versions offered by Chomsky and Murray Cohen. Aarsleff has written (what I believe is) the most thoroughly documented and closely argued account of language study that we have as yet.

Thomas Willard

Tueson, Arizona

Ian Hacking replies:

I welcome Thomas Willard’s cogent but modest defense of the claim that Locke was attacking Adamism. Where Aarsleff had written that Adamism was “the most widely held seventeenth century point of view,” Willard notes that earlier central inhabitants of that century had dismissed it. I still don’t quite understand the thesis advanced by Aarsleff and Willard. For example, Willard says that “the language schemes of John Wilkins and the Baconians in the Royal Society never escaped the visions of Lull,” while Aarsleff says that Locke, in his critique of the Adamic doctrine “agreed with many of his great contemporaries, e.g. […] John Wilkins.”

My point, in the passage of my review cited by Mr. Willard, was this. Aarsleff writes as if Locke’s distinction between natural and conventional signs was motivated by his anti-Adamism. It is important that this distinction was revived in the seventeenth century. But we find it in Hobbes, who, as I wrote, did not care about Adamism one way or the other. We also find it in the 1662 Port Royal Logic, from which Locke learned much else, and which is equally indifferent to Adamism. So I thought that Aarsleff’s emphasis on this distinction to establish Locke’s anti-Adamism was a bit thin. Willard states some better reasons for taking that interpretation seriously.

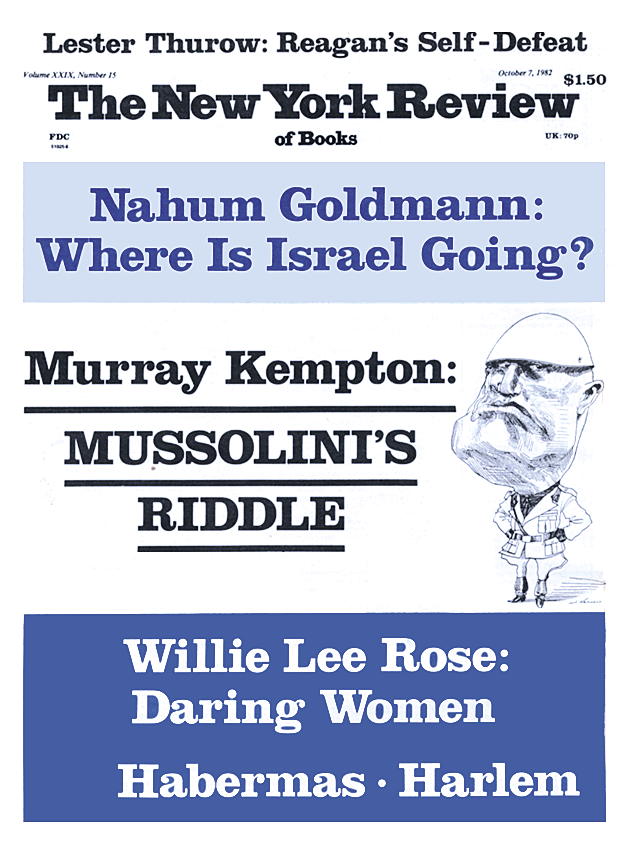

This Issue

October 7, 1982