“There is no secret of the psyche that Caravaggio cannot find out,” writes Professor Freedberg of the artist’s Death of the Virgin, which now hangs in the Louvre, disfigured by dark varnish. Although he elaborates on his meaning, this is the most surprising sentence in his book—indeed, the most surprising sentence in any of the three books under review. Was Caravaggio trying to find out the psyche’s secrets? Did artists ever try to do this, even in portraiture (a branch of painting, incidentally, in which Caravaggio seems to have been singularly unsuccessful), before the middle of the last century? And even if we assume that artists can find out the secrets of the psyche, how do they reveal them to us?

For Alfred Moir the St. John in the Borghese Gallery in Rome (possibly Caravaggio’s last painting) is perhaps indulging in “fantasies of physical gratification”; for Sydney Freedberg the communion between the artist and the model is here “a gentle, tragic-seeming one, which knows too well the transience of the mortal world.” Such apparently conflicting sentiments are (alas) certainly not incompatible—but, whether separate or combined, they are excessively difficult to convey in any picture that does not depend on a familiar story. For Freedberg this picture appears to reflect an aspect of Caravaggio’s own psyche: but that psyche remains tantalizingly inaccessible to us.

Many people today would agree with the authors of all three books that the Death of the Virgin is a work of extraordinary emotional power. “Mary lies on a kind of litter, a poor woman, plainly dressed and barefoot, too weak to have crossed her hands in prayer and too worn even to welcome the release of death”—the vivid description is Moir’s. The stark room is barely indicated, but the falling folds of a heavy red bed hanging which has been attached to the ceiling give the scene a certain grandeur. The Magdalene, in orange and white, sits on one side of the bed, her head bowed in grief; on the other side stand the tall, robed, barefooted Apostles—those who are near the stiff, ungainly corpse gaze at it with reverence and sorrow, those at the back of the room appear to be talking gravely among themselves.

Caravaggio was already a very famous artist when (in the early years of the seventeenth century) he painted this altarpiece for the family chapel of a papal lawyer in the church of S. Maria della Scala in Trastevere in Rome; but not long after its installation it was removed and put up for sale because the Carmelite Friars, to whom the church had been entrusted a few years earlier, objected to Caravaggio’s treatment of the subject. After the event (but while memories of it were still fresh) a number of writers gave similar (though slightly differing) reasons for the objections caused by the picture. Caravaggio, it was said, had used a prostitute as a model for the Virgin (the church of S. Maria della Scala had in fact originally been built for a foundation devoted to the care of reformed prostitutes); “he had portrayed the Virgin with little decorum, swollen and with bare legs”; “he had shown the swollen body of a dead woman too realistically.” Since two of his previous altarpieces had already been rejected by other churches apparently for infringements of decorum, these reasons seem likely enough.

Modern art historians have, however, suggested that by showing the Virgin as a corpse rather than in “transit” from this world to the next, as was conventional in depiction of the theme, Caravaggio’s picture was also open to theological objection; and as we are told by the well-informed author of a seventeenth-century guidebook to Rome that the artist who was commissioned to paint a substitute for Caravaggio’s altarpiece was specifically instructed to insert into his picture a glory of angels, even after he had already shown a dignified Virgin with hands clasped as she faces her earthly end, such a conclusion seems inescapable. Must we therefore assume that Caravaggio was a crypto-Protestant, even perhaps an unbeliever? At least one American art historian seems to have reached this conclusion recently, though the evidence he provides is hardly compelling.1

The Death of the Virgin was bought, for a high price, by the Duke of Mantua. His agent in Rome was a little puzzled by the extraordinary esteem in which the picture was held, but he was persuaded that it must be good by the enthusiasm of Rubens (who acted with him in the purchase) and by the unanimous opinion of the painters of Rome who insisted that it should be exhibited there for a full week before being removed from the city. Caravaggio himself played no part in the transaction: he had fled to Naples after having killed a man following the disputed results of a game of tennis—the latest, but not the last, in a series of violent episodes which punctuated the last ten years of his life, beginning apparently at the very moment that he emerged as a great religious painter.

Advertisement

But the phrase “great religious painter” perhaps begs the question. We have seen that even today not everyone will accept such a verdict, and in Caravaggio’s lifetime it would certainly have been questioned. It was above all his fellow painters (with admirers like Rubens, who cares about detractors?) and the leading members of a powerful and sometimes unscrupulous aristocracy who were enthusiastic about this artist who introduced into his altarpieces unforgettable portrayals of the humble and the devout. The clergy might sometimes object to these pictures, but they were snapped up by bankers and cardinals and princes. Theorists and theologians might deplore his faults of decorum or doctrine, but sophisticated patrons cared nothing for such lapses. As the agent of the Duke of Mantua acknowledged, Caravaggio was “one of the most famous for the collectors of modern things in Rome.”

His earliest masterpieces were enticing pederastic images painted for a cultivated and dissolute cardinal; his most wonderful late picture (The Beheading of St. John the Baptist in Valletta—see illustration on page 26) was produced in gratitude for the keenly desired knighthood he received from the Grand Master of the Knights of St. John in Malta. No artist has ever been more closely, more desperately, attached to the elite than the violent and perhaps unorthodox Caravaggio, to whom a fine radical critic of today feels closer than to any other painter of the past because.

he was the first painter of life as experienced by the popolaccio, the people of the back streets, les sansculottes, the lumpenproletariat, the lower orders, those of the lower depths, the underworld—interestingly enough there is no word in any traditional European language which does not denigrate or patronize the urban poor it is naming. That is power.2

But what did the popolaccio itself think of this artist who—as Berger rightly emphasizes—gave it such natural dignity (in our eyes, at least)? We have only one fragment of indirect evidence. In his Madonna of Loreto (still in the church of S. Agostino in Rome for which it was painted) Caravaggio showed two peasants, one of them very old, kneeling in front of the Virgin and Child (a most elegant and courteous Virgin, and, though apparently the portrait of a prostitute, with features very unlike those of the corpse he was to paint a year or so later). The man’s bare and muddy feet almost emerge from the frame at the bottom of the picture. A hostile source tells us that because of trivial details such as this and the woman’s dirty cap “the people made a great fuss of the picture” (da popolani ne fu fatto estremo schiamazzo), and—as Howard Hibbard points out—when taken in context these words seem to be scornfully implying “that the simple people who were portrayed in Caravaggio’s picture saw it and approved of it.”

A very high estimate of Caravaggio is now widely accepted; and no one can slip through the illustrations in any of these books without being overawed by the intensity of a spiritual development which within less than twenty years took him from pretty scenes of equivocal frivolities to scenes of stark grandeur which rival in moral seriousness the finest works of Giotto and Masaccio. In the preface to his admirable book Hibbard tells us that Caravaggio’s

paintings speak to us more personally and more poignantly than any others of the time. We meet him over the gulf of centuries, not as a commanding and admirable historical figure like Annibale Carracci, but as an artist who somehow cut through the artistic conventions of his time right down to the universal blood and bone of life. Looking back almost four hundred years, we see him as the first Western artist to express a number of attitudes that we identify, for better or worse, as our own. Ambivalent sexuality, violent death, and blind faith in divine salvation are some of the contradictory messages and images that pervade his works.

Moir evidently feels much the same (though it is regrettable that he finds it necessary to allude to Tennessee Williams, Jean-Pierre Belmondo, and other contemporary figures to make the point).

This is fine, but it raises the worrying question of what will happen to Caravaggio’s reputation if—as so many people seem to be hoping these days—we should one day become sexually straight and peaceful and hold very different views on the nature of salvation.

The question is pertinent because there has recently been published in Italy an (annotated) edition of an earlier monograph on the painter by one of this century’s most distinguished art historians, who was also a pioneer in the “rediscovery”—or perhaps “discovery”—of Caravaggio as a great and serious artist.3 It is already difficult to convey the extraordinary authority exercised by Roberto Longhi until his death in 1970. The Italian—even the international—art history community was split between “Longhians” and “anti-Longhians”; his excommunications of such celebrated artists as Tintoretto and Tiepolo were read with awe even by his enemies, who were mesmerized by the power of his mind and his amazing command of language; and in the review that he edited his talented disciples built up around his name a “cult of personality” scarcely to be equaled outside Stalinist Russia.4 The reconstruction and characterization of Caravaggio’s achievement was one of Longhi’s most committed and thrilling tasks. Yet although the final version of this reprinted monograph was published as recently as 1968, to read it now, in the light of Hibbard and Moir and Freedberg, is a sobering experience which tells us much about their own contributions to our understanding of the artist.

Advertisement

We are told by his editor that Longhi was stimulated to study Caravaggio by his visits to a Courbet retrospective held at the Venice Biennale in 1910, and he was certainly determined to recuperate Caravaggio as the true ancestor of modern art, as the term was then understood. How different Caravaggio seems in this perspective—and, paradoxically, how much closer in some respects to the painter described in the seventeenth-century sources than to the tortured and spiritually profound genius we have learned to admire.

Realism is the key to Longhi’s view: if Caravaggio paints fancy-dress pictures of good-looking boys at the beginning of his career, that is because poverty has compelled him to draw on his friends and contemporaries for models—possible references to the homosexual nature of these pictures are so oblique that we cannot be sure that Longhi intended them at all, and on other occasions he certainly derided such interpretations, and those who made them. Longhi indicates the importance of patronage, but never explores its significance; if a document appears to conflict with stylistic analysis it is given short shrift. Caravaggio emerges as a difficult character, but one whose difficulties arose essentially from his conflict with the hypocrisies of conventional art and society. He is a bohemian who puts his experiences to direct use in the creation of freshly observed and intensely felt pictures whose imagery springs from the popular proverbs and taverns of early seventeenth-century Rome and later Naples.

Above all, Caravaggio is celebrated as the brave, rebellious, and true ancestor of much of the greatest painting that was to emerge in the decades and centuries following his death, from Velazquez and Zurbarán, Rembrandt and Vermeer, to Courbet and Manet—but (like Courbet, Manet, and the Impressionists) his achievement was greeted with critical hostility and could only be recognized by the exceptionally sensitive dealer (an explicit allusion is made to Durand-Ruel) and by equally adventurous and courageous artists: David’s Marat, claims Longhi, is a Caravaggesque portrait but Caravaggio scores over the French revolutionary painter because he never painted an equivalent of the Coronation of Napoleon. Thus Caravaggio is the heroic archetype of the unorthodox and misunderstood genius who, in the light of hindsight, can be seen as a central rather than a peripheral master.

Longhi’s book remains something of a masterpiece, and many of his observations are developed or implicitly challenged in these newer accounts of the artist’s career. It was Longhi, for instance, who first sought the spiritual and artistic origins of Caravaggio’s style in the sixteenth-century “realist” painting of his native Lombardy. Hibbard and Moir accept this, and the illustrations that demonstrate the point in Moir’s book are valuable and telling. Freedberg is skeptical, however, and he sees Caravaggio as far closer to Annibale Carracci than to his provincial roots.

The issue is crucial (as well as controversial—at least one of Freedberg’s analyses of a picture directly conflicts with the claims made for it by Hibbard), for it raises the question of how far there was a general, and self-conscious, revolution in the arts “around 1600,” the theme of Freedberg’s three reprinted lectures. Of the painters who at this period were moving away from convoluted artificiality to a more direct and solid style on which the future could build, Caravaggio is for him neither the greatest nor the finest. Both Annibale and his cousin Lodovico Carracci established precedents that were vital for him, and although Freedberg writes with very great sensitivity about some of Caravaggio’s pictures, others (including one of his supreme masterpieces) are omitted altogether and he is given less space than the Carracci. Yet such an approach has the stimulating effect of bringing Caravaggio more into the mainstream of art despite his personal idiosyncracies, and to that extent (but to that extent only) it conforms to Longhi’s interpretation.

For Freedberg, as for Longhi, Caravaggio is a central figure in the history of European painting, but for him this is not so much because Caravaggio radically differs from more traditionally minded painters, as because, in the case of the better of them (the Carracci), he shares some of their ideals, and Freedberg stresses these parallels wherever he can. Thus Caravaggio should be thought of as a leading participant in the creation of the classicizing naturalistic style which is one of the great achievements of the age: it is a pity that the necessarily restricted form of Freedberg’s book has not allowed him to develop the implications of this argument in greater detail.

Yet Freedberg certainly does not accept (and Hibbard specifically rejects) the view hinted at by Longhi, and very popular in some circles, that as a near contemporary of Galileo, Caravaggio should be conceived of as one of a number of men who broke through stale conventions to pioneer a scientific and naturalistic approach to the world around them. And because he is essentially concerned with stylistic change Freedberg shows little interest in the imagery of those early pictures of Bacchus, or of such paintings as the Boy Bitten by a Lizard, which for Longhi were no more than lighthearted exercises in observing his friends dressed up in fancy clothes, but which have attracted such a vast amount of attention in recent years.

The absurdity of much writing on the subject defies belief. Even those who have struggled bravely with the more abstruse interpretations now sometimes given to pictures by Piero della Francesca or Giorgione will be startled by the complex Christian symbolism that has been read into a Bacchus by Caravaggio (here, indeed, would be a “secret of the psyche”!). Both Moir and Hibbard write excellently, and undogmatically, about the teasing issues raised by such paintings, pointing out the dangers of oversimplification as well as overelaboration; but both are still baffled by the strangest and most blatantly perverse picture of a nude youth that Caravaggio ever painted (for an apparently perfectly respectable patron), and, like writers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they can suggest no titles more specific than Youth with a Ram or St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness(?).

Moir’s book follows the conventional Abrams art-book pattern. There is an introductory essay with nearly a hundred black-and-white illustrations, many of them well-chosen comparative material which is not easily accessible, followed by forty-eight decent color plates to each of which is devoted about a page of text; there is also a critical bibliography. About three or four of the pictures reproduced would not be accepted by all authorities as works by Caravaggio (and Moir himself has doubts about some of them); and it has not been possible to include a recently discovered and documented picture (The Martyrdom of St. Ursula) which was shown at the Neapolitan exhibition held in London and Washington. Though the text is written in an easy style it reveals the results of hard thinking (as well as of the author’s earlier publications related to Caravaggio) and it is always reliable, and often original.

Hibbard’s monograph has eight colored illustrations and nearly two hundred in black and white. Until our age abandons the “ambivalent sexuality, violent death, and blind faith in divine salvation” which the author finds characteristic of it, this seems bound to remain the standard book on a great and enthralling artist. It is hard to imagine a better one, though it is sure to stimulate fresh and perhaps antagonistic interpretations. The painting of Caravaggio is studied in relation to its historical background, artistic sources, patronage, and his own temperament. Psychoanalytical hypotheses are suggested when plausible but never pressed too hard. There are detailed notes on all the pictures accepted by the author or by other serious authors. Relevant contracts are quoted in the notes, and at the end of the book the principal sources for Caravaggio’s life are printed in the original languages and in translation.

Human nature being what it is, these invaluable additions make one rather regret that space could not also have been found for a full transcription of Caravaggio’s trial for libel (which is not easily available) and even for the many police charges against him which are often revealing. However, the influence of born-again Christians notwithstanding, the characteristics of our age are not likely to change drastically in the near future, and this can therefore be remedied when new editions are published.

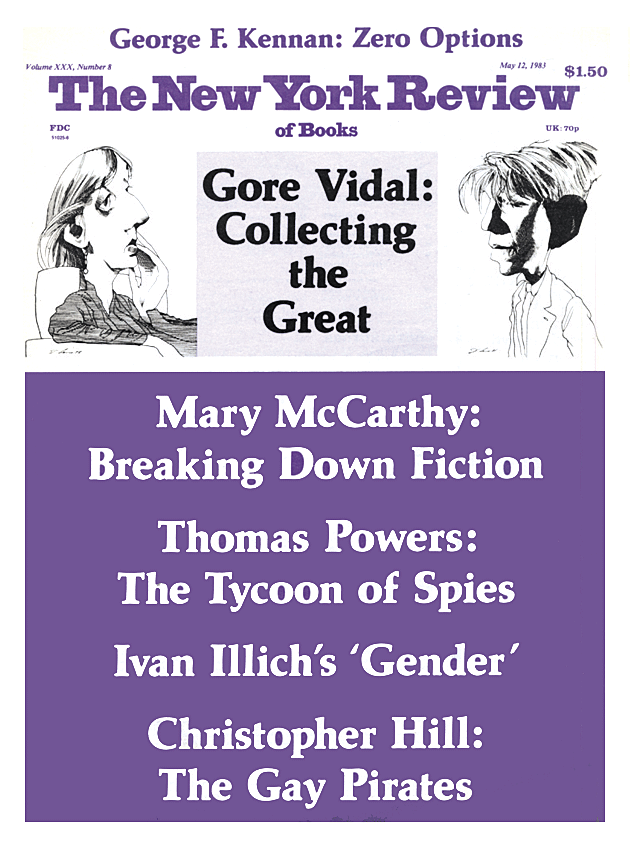

This Issue

May 12, 1983

-

1

Stephen Pepper in Le Arti a Bologna e in Emilia dal XVI al XVII secolo (Bologna, 1982), pp. 196-197; he is incidentally wrong to claim that Saraceni’s altarpiece recently in the Heim Gallery, London (see catalogue 25, 1976), was the one accepted as a replacement. ↩

-

2

John Berger in The Village Voice, December 14, 1982. ↩

-

3

Roberto Longhi, Caravaggio, edited by Giovanni Previtali (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1982). ↩

-

4

Some of the flavor is conveyed in the recently published papers of a colloquium on him, also edited by the very able and very faithful Giovanni Previtali—L’Arte di scrivere sull’Arte—Roberto Longhi nella cultura del nostro tempo (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1982). Among the contributions is one on the textual variants to be found in his monographs on Caravaggio. ↩