Jonathan Miller’s book is based on a British television series in which he quizzed fifteen “psychological investigators,” and that includes philosophers, an anthropologist, and an art historian as well as white-coated men from the laboratories. The level of the dialogue is often quite abstruse yet always lucid, and greatly helped by the polymath interviewer, who wraps up the topics in happy analogies and crisp turns of phrase of his own. Even if one allows for possible bias in the interviewer’s choice, it makes an interesting exposition of the current state of the art in the study of humankind.

First, not a behaviorist or an animal experimenter among them: each of the contributors in his own way is at least trying to grapple with human experiences. Second, fragmentation of the discipline, as ever: like Stephen Leacock’s horseman, psychology rides off in all directions. Miller, who perhaps has a love-hate affair with psychoanalysis, includes three contributions on it, though only one—Hanna Segal’s—by an analyst; the other twelve contributors are seldom anywhere near that wavelength. What can Melanie Klein’s theory of the six-month-old baby’s unconscious emotions, as expounded by Segal, have to do with Richard Gregory’s discussion of visual mechanisms, Daniel Dennett’s model of brain as computer, or Rom Harré’s analysis of social convention? Each “psychologist” in his little sound-proofed cubicle plays games with his own metaphor and tries to make sense of one corner of experience looked at from one direction; few make any reference to the others’ work. Freud, who at least tried for comprehensiveness, does in fact get the longest entry in the index—just slightly longer than “art,” “brain,” “consciousness,” “language,” and “nervous system.”

What is now new again and altogether excellent is that art, language, and consciousness have become permissible subjects of discussion for psychologists. And most striking of all, that formerly forbidden four-letter word “mind” has no fewer than fourteen index entries in the book. Professor George Miller of Princeton, whose historical sketch opens it, does in fact go right back to 1890 to appropriate William James’s definition of psychology—“the science of mental life”—as his own, and claims that this is what holds the various different approaches together. This is a new, mentalistic psychology, a thorough repudiation of the behaviorist program in which only what could be seen and measured was of any account. And the curious thing is that it is machines that have brought back mental life into psychology. Devices such as radar, servo-mechanisms as employed in aiming guns, and of course computers have an “inside” that cannot be inferred behavioristically: they have scanning abilities, memory storage, purposiveness, and, by implication, a kind of expectation. They have provided new models for conceptualizing a mind as opposed to mere brain. So, as George Miller has said, “the mind came in on the back of the machine.”

Jerome Bruner’s contribution brings out other turning points in the run-up to the new psychology. When Heisenberg showed as early as 1932 that there are different kinds of knowledge that cannot be held simultaneously—for example, the position of a particle and its velocity—it was a blow against the assumption that facts are simply “out there” for us to discover; rather, the mind chooses and structures its knowledge. Then, the machine again: even in the early days of cybernetics, investigators were becoming interested in the nature of knowing, its active selectivity and self-regulation. The real beginning of the “cognitive revolution,” however, Bruner dates at 1956, when Chomsky first put forward ideas about innate capacity for language, and Bruner himself in his Study of Thinking developed the notion that rational thinking strategies need taking apart for study just as much as the Freudian irrational. (He was not, though, quite the first, as he claims, to do so; the Würzburg psychologists early in this century also had a stab at it, from introspection rather than experiment.)

All the same, in 1956—and much later—the official dogma was behaviorism, and though signs of a coming cognitive revolution may have appeared nearly thirty years ago the ideas that Miller’s guests expound are of the 1970s and 1980s. In spite of the heterogeneity of these dialogues it is just possible to extract some common current themes; and one of the chief, so clear in George Miller’s and Bruner’s contributions, is the idea that we structure our world ourselves, through our own innate perceptions. We have all heard about this, but we go on assuming that “things” are out there in the world while we lodge somewhere in our heads observing them.

Richard Gregory’s work with visual illusions at the University of Bristol is particularly relevant to the theme. Everyone, he finds, when presented with ambiguous and misleading diagrams structures them into some kind of sense; it is as though the visual brain, rather than just registering, makes guesses and takes decisions about what is put in front of it—and it does the same thing all the time with more ordinary material, drawing on notions of probability and past experience. Jonathan Miller and Gregory go on from this to take wonderful flights of fancy: that perception is, so to speak, a kind of science proceeding from hypothesis to hypothesis, that natural selection will gradually evolve a human brain incorporating a more and more accurate model of the world, that if we only knew how to “read” brains we could look at the brain of a Martian and infer what its world was like—in a “sort of Lascaux painting of neurological activity inside the brain.”

Advertisement

The conversation with Ernst Gombrich presents the same idea in relation to the naturalistic visual arts: they are not, as the old aesthetics assumed, better or worse copies of nature, but inspired combinations of a mass of traditions, illusions, and devices for representing the world’s appearance. Rather than transferring a naive copy of what they see onto the page, artists learn as much from other artists’ devices as from nature; and the spectators too learn to read a picture, to make inferences from shadows and blobs and foreshortening, and meet the artist halfway. They are affronted when a change of style means a change in reading; trees, to the public first viewing impressionist pictures, were meant to be a burnt olive color, not the fresh green we accept now. Once again Jonathan Miller compares this making and matching of the artist with a scientist’s work, and, as he says, it coincides with Gregory’s views about the constructional character of perception: “The traditional picture of the mind as a mirror of nature has given way to one in which active conjecture plays a leading role.” Or, as Professor George Miller says yet more succinctly, “The main intellectual accomplishment of the nervous system is the world itself.”

A second theme common to these dialogues follows on from this—a new interest in the unconscious, and not the censored, repressed, emotional unconscious of Freud but the extraordinary repertoire of innate skills and strategies which we clearly use all the time without being aware of it. These new Freuds are astonished all over again by the gap between what we consciously know and what remains out of our ken. “Our own access to what’s going on in our minds is very impoverished,” says Daniel Dennett of Tufts University. “We often confabulate, we tell unwitting lies, and we are often simply in the dark; we have no idea at all.” And as Jerome Fodor of MIT says: “No one is quite clear why one should have as little access to one’s mental processes as it turns out one has. People go around saying in a slightly downcast tone of voice that maybe one ought to put the question the other way round, and treat consciousness as a sort of pathological mental condition, the exceptional case.” This is the iceberg view of mind, in which only the tip is ever visible, but without the Freudian censor as explanation—hence the puzzlement about the inaccessibility of so much of ourselves.

In this context the name of Chomsky comes up several times; the Chomskyan unconscious, which proceeds from the idea that the infant is born with an innate prestructured endowment for language, interests these psychologists more than the Freudian one—and it is seen as even more inaccessible. Unlike the Freudian unconscious, it offers no bonus for being revealed; as Fodor remarks ruefully, “It’s not so clear what massive introspectability would buy one. It would just make psychology a lot easier.”

Thirdly, this unconscious, as well as being the mysterious source of language acquisition, is agreed by many of the speakers to be the repository of symbol and image—words which are once again respectable. “Man is an animal that represents the world symbolically,” says one; the mind is “essentially a symbol-processing system of some kind,” says another. They vary, of course, in what they mean by symbol. For the psychoanalyst Hanna Segal symbol formation is linked with infantile interest in the mother’s body—“I think that things which are not endowed with symbolic meaning at some level probably don’t interest us” (what about bodies themselves?). Rom Harré of the State University of New York discusses social psychology in terms of the symbolic devices that give us a cultural history as well as a biological one: “We construct our worlds in talk of various kinds. Every exchanging of symbolic objects is a kind of extension of that conversation, I believe.”

The new interest in the mental image—dropped a long time ago because it smacked of armchair psychology rather than laboratory work—differs greatly from the old introspective methods or the delightful Galtonian pastime of collecting images like stamps or pebbles (“A is brown…. E is a clear, cold, light-gray blue…. R has been invariably of a copper color, in which a swarthy blackness seems to intervene, visually corresponding to the trilled pronunciation of R…”). The idea that inside the head there is a pack of picture-thoughts that get dealt out as the situation demands will not do, it is pointed out here; how do you have an image of a man not scratching his nose, or of a thousand-sided figure? But as concepts, rather than images, they are perfectly easy to manage. “Thought,” whatever it is, can certainly take place extraordinarily fast, extraordinarily far from consciousness, and both with and without pictures and words. As Francis Galton himself said in the late nineteenth century: “It often happens that after being hard at work, and having arrived at results that are perfectly clear and satisfactory to myself, when I try to express them in language I feel that I must begin by putting myself upon quite another intellectual plane. I have to translate my thoughts into a language that does not run very evenly with them.”

Advertisement

The psychologists of the “cognitive revolution” are tackling the hardest problems in psychology, ones that were abandoned some seventy years ago without solution, and Fodor in his dialogue with Miller is realistic in saying that though some small specific mental tasks like sentence-processing have been successfully studied, “when we try to understand less specialised intellectual processes: solving problems, writing plays, experimenting in science, and so forth, it seems to me that the dark ages are still upon us.” They call upon modern metaphors—information theory, artificial intelligence—but find them falling short of answering most questions about thought. How maddening that as well as being able to conceptualize (like a computer) a man not scratching his nose, some people can also conceptualize a man scratching his nose and (pace Galton) instantly tell you the color of his eyes, style of his clothes, and expression on his face! Quite unlike a computer—and already the nub of a play.

Perhaps there is a clue to the nature of thought somewhere in the process of dreaming. Contrary to stereotype, good dreams—for they vary in quality—are not ludicrous and chaotic. (By the imagination, said Darwin, man “unites former images and ideas, independently of the will, and thus creates brilliant and novel results”—and “dreaming gives us the best notion of this power.”) In the dream, as Susanne Langer points out, the visual image can be fraught with intense meaning, an abstraction made visible. The dream can also conceptualize negatives, and juxtapose strip-type narrative line with metaphysical import; a dream might be “about,” for instance, “beginning-ness” though we tend to push it into visual or narrative shape on waking since we have an inadequate vocabulary for “-ness” words. Dreams can also use words, puns, and rhymes, metaphor and simile, devices such as a story within a story, and of course tremendous condensation, so that what took an instant in the dream needs paragraphs of explanation in the waking state. If our “deep” daytime current of thought is like this, if Freud’s dream work is not unlike waking work, the psychologists have a long way to go.

Langer in fact in Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling suggests that primitive man’s first consciousness emerged from dream states, and bases her picture of homo symbolicus on this. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz of Princeton puts the symbol-making, imaging drive into a social perspective very like Langer’s, comparing symbolic behavior in Western society with that in less developed communities. He argues that we no longer see dancing for rain or chanting over crops as primitive and childlike; people in these communities also take great care over the practical care of their crops, and the dancing and singing is not simple wish-magic but a celebration of the whole community’s involvement with the agricultural cycle. What are we to make of our own unritualistic, rational society then? asks Miller. Geertz argues that we are by no means without symbolic ritual—in government and the law, for example; and also that “odd…phenomena occur because the normal course of symbolic formation has been frustrated”; people will look for symbolic meanings somewhere because it is their nature. (He might have added that symbolic activity depends on the vitality that its participants endow it with: a wedding or a burial may be either deeply moving or a dreary farce.)

These are some of the guiding threads that emerge from as mixed a collection of scholars and ideas as one can imagine. It is all much more exciting than the pecking pigeons and running rats of the old school, though these new themes and models will also eventually have their day and be replaced by new ones. Whether the central riddles are going to yield up their secrets entirely is, fortunately, doubtful.

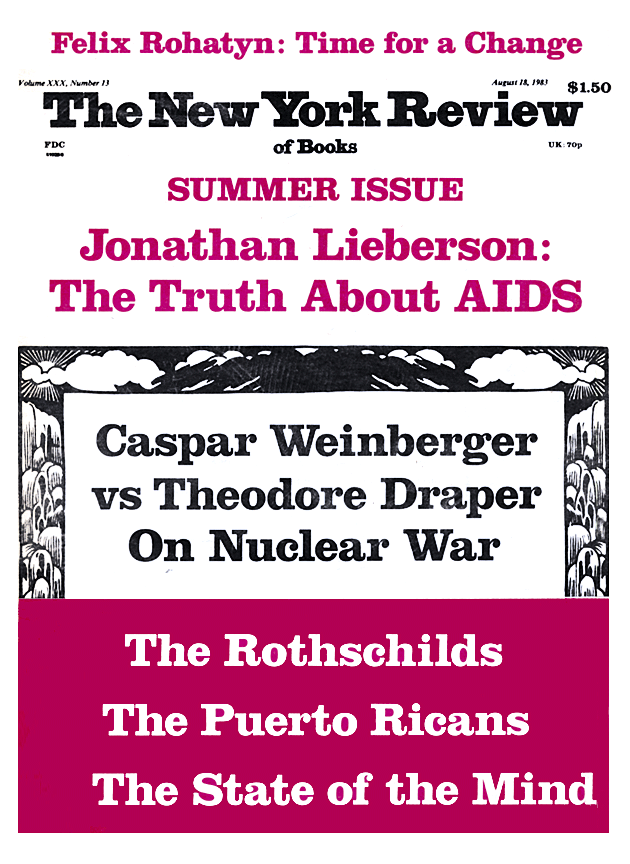

This Issue

August 18, 1983