The story of Bluebeard; who married seven wives and killed six of them, until the seventh went exploring behind a forbidden door, seems to have its roots in the folklore of Celtic Brittany. Perhaps the original Bluebeard was a sixth-century tribal chieftain named, delightfully, Comorre the Cursed; perhaps before that he was a priest, an order of priests, or a deity with a penchant for human sacrifice. (His blue beard, otherwise irrelevant, may recall the ancient practice of staining oneself blue with dyer’s woad.) The story has dozens of analogies from dozens of different countries and cultures; it is evidently a deep female fantasy of which ripples are still felt in nineteenth-century novels like Jane Eyre and in the thousands of cheap romances which to this day rewrite with little or less literary skill this fable of female innocence and male villainy.

In the course of history, the story of Bluebeard got attached (rather adventitiously, for a fact) to the name of Gilles de Rais (or de Retz), fifteenth-century marshal of France, who had fought in the English wars alongside Joan of Arc. After squandering his enormous inheritance, Gilles took up alchemy as a quick way to wealth, and meanwhile, as an independent diversion, began kidnapping from the Breton peasantry children, mostly boys, whom he tortured and murdered. His final count has been estimated as high as 140; but Gilles had only one wife, and he did not murder her. She left him, and after due inquiry his misdeeds were uncovered. He was hanged in 1440.

Thus Bluebeard’s story, apart from being quite different, long antedated him. Gilles was grafted onto it, or it onto him, two scions of the same evil stock. In the late seventeenth century, Charles Perrault, already known for his verbal duels with Boileau over the ancients-vs.-moderns question, included “Bluebeard” in a set of prose fables which we know today as the Mother Goose Tales.

Max Frisch, who has revived (and revised) the story of Bluebeard in a short, quasi-parabolic book, is a versatile Swiss man of letters with a practiced talent for deliberately fragmented and enigmatic writings. I’m Not Stiller, his first, best-known, and still best book, studied a divided personality, one element of which was intent on repudiating the other; its theme of guilt disintegrating a nonpersonality only vaguely aware of what was being done to it would provide a constant pattern for Frisch’s work. Homo Faber was a fable of technological man brought to destruction by the ancient Fates—as well as by an inopportune itch for slender easy young things. Man in the Holocene, though ostensibly about a single senile citizen overwhelmed by his past and fading out in the Ticino, was full of portentous echoes about the deteriorating human condition. Thus one can hardly help reading Bluebeard for its overtones, especially since its texture as a narration is diaphanous and full of holes. Dr. Felix Theodor Schaad, a Zurich specialist in internal medicine, has married seven successive wives, and is accused of murdering the sixth of them, Rosalinde Zogg. We are told from the first that a jury has found the doctor not guilty by reason of insufficient evidence. The book consists of the subsequent legal processes that take place in the private forum of his conscience. Schaad’s friends and acquaintances are interrogated; so are all his seven wives, including the momentarily resurrected victim. A cleaning lady, an antique dealer, the doctor’s nurse, a custodian of the cemetery, a janitor and his wife are also called to testify. And testify they do, invariably to inconclusive effect. Dr. Schaad himself goes over his story again and again—not to establish an alibi, for in fact he has none, but to correct details of his story, relevant or irrelevant, which he did not get right or could not recall in previous interrogations. Though he has been found legally innocent, he feels deeply guilty; and by reenacting his own court-room drama, often with fantastic variations, he hopes at least to allay part of that guilt.

All in all, the doctor makes a sad witness. He is repeatedly caught in contradictions and flagrant misstatements; his replies to questions are almost always evasive and often entirely irrelevant. For some striking episodes of his behavior he cannot account at all. (Since the trial scenes take place entirely in his head, one can never be sure how far the weakness of his replies is “real,” how far it results from a basic desire to find himself guilty.) But a great deal of the doctor’s background is dim, for no better reason, apparently, than that the author would have it so. We do not know why he married so many wives, or why he left them, or whether they left him. Various phantasmal females materialize from time to time, unidentified and unidentifiable; one suggests suicide to him, and offers him the means to commit it, another holds his hand as he emerges from a coma on a hospital bed.

Advertisement

Motives are equally blurry. Dr. Schaad was either pathologically jealous, as described by several of his wives, or extraordinarily complacent in the face of another wife’s infidelities. Andrea, the second wife, testifies that when he learned of her unfaithfulness, he was upset, went away, wrote her a long letter which now lies before the court (but of which the reader learns nothing), and thereafter, when he got drunk, which was frequently, delivered long lectures, and always on the same subject—but Andrea cannot remember what the subject was. As for Rosalinde, the victim, we learn that she never enjoyed sex, though she had numerous affairs, and after her divorce from Schaad became a call girl. She either was or pretended to be an intellectual; she had many friends in “good” society, and gave frequent parties for them; she remained on good terms with her ex-husband, yet demanded that he watch her coupling with her customers. (Her aim was to “cure” him of a jealousy that he says repeatedly he no longer felt.) If these are people, a reader wonders, what do they think they’re doing?

In short, the book, like several of Frisch’s previous narratives, is an extended exercise in tantalizing and bafflement; it systematically withholds information, gives contradictory information, gives irrelevant answers to requests for information, or gives deliberately trivial information (as about a childhood rabbit named Pinocchio). The author is particularly evasive in defining the mental processes of his characters, either by professing frank ignorance or by silently ignoring them. One doesn’t have to be a particularly sensitive or suspicious reader to realize early on that the process of interrogation is going to reveal nothing that’s definitive and very little that’s even relevant to the alleged object of inquiry.

On the other hand, physical circumstances seem very much against the doctor. Rosalinde Zogg was murdered in her apartment, to which he possessed a key; so far as we are told, he was the only person, apart from the victim, who possessed such a key. He was the last person known to have seen her alive. The circumstances of the gruesome murder—the lady was suffocated with a used sanitary napkin and strangled with one of the doctor’s neckties—clearly mark it as a crime of passion, not a failed burglary, or anything of the sort. The doctor’s three attempted alibis—that he was walking in the woods, that he was working on tax matters in his office, and that he was attending a Czech movie—are successively demolished. The victim could not have opened the apartment door from the inside because she was under heavy sedation; the doctor’s car could not have been where he said it was, because it was in the garage. The interrogation proceeds, meanders, recapitulates, is frequently interrupted; but, as a reader can hardly help anticipating, it leads only to uncertainty tinged with heavy suspicion.

After his acquittal “for lack of evidence,” the doctor’s practice, not surprisingly, dwindles; eventually, he disposes of it. His seventh wife returns from Kenya with a new acquisition, Herbert. She says calmly that she is leaving the doctor, and he accepts the decision calmly. He is tormented by fantasies of suicide, drives to his native village, and there confesses the murder. His confession is rejected as false, another person entirely has been charged with the murder and is in custody. Driving back to Zurich, he crashes, probably on purpose, into a tree, and is nearly killed. Perhaps he is killed: that too is left indefinite, as was the fate of Walter Faber at the end of his book.

The mini-Bluebeard, in short, turns out to be a non-Bluebeard; the doctor, a true self-tormentor, has worried himself into a state of suicidal guilt—and all, it would seem, for nothing. In a common mystery story, the author would be expected to provide some evidence that the “real” murderer could have done the deed, and had some sort of motive for doing it. The author would even have dropped some unobtrusive clue which could be picked up, reinterpreted, and used to convict the murderer. Not in Frisch’s Bluebeard: the guilt here is shifted to a character, hitherto nameless—a Greek student, bald, with a black beard, speaking no German. How he did it (the door locked, the victim in a stupor behind it, the janitor and his wife unseeing) we are allowed to guess. Why he did it, since the reader does not have even a hint of the rudiments of a motive, is an even wider and wilder speculation.

Advertisement

Such are the outlines of Herr Frisch’s shaggy dog fable. It is sparsely written, mostly in dialogue, with few transitions and hardly any introductions; characters appear (sometimes from beyond the grave), testify or decline to testify, and dematerialize. Locales and periods change phantasmagorically; perhaps the doctor took a trip to Japan and Hong Kong, or perhaps he just read about those places in his waiting-room magazines. The particularly revolting character of the murder seems to saturate the book’s atmosphere; and of course the verdict, handed down at the beginning of the book, is really no verdict at all. So the book is spooky, even if it is not a mystery, and confirms the sense one gets from Frisch’s career as a whole that he’s a skilled contriver of mind-entangling labyrinths, after the fashion of Kafka and Borges.

On the other hand, there are some Mitteleuropa preoccupations that hover around Bluebeard, to which the unsuspicious American reader might be alerted by a glance at the recently reissued Sketchbooks. * Frisch as a German Swiss is much exercised by the question of German war guilt, by the atrocities of the concentration camps and the fearsome destructiveness of the Hitler regime. For any serious person, it is an ugly problem; a great nation cannot be told to wallow indefinitely in its own guilt, far less in the guilt of a generation now by and large consigned to history. Yet the wrongs done during the Holocaust and the war were hideous, unforgivable, and, in the literal sense, unforgettable. The historic record, for those who can stand to look into it, is searing; the wound on the moral conscience of the West seems likely to be unhealable.

It was Jules Michelet who called Gilles de Rais, the avatar of Bluebeard, a bête d’extermination; I do not know if Herr Frisch had in mind this phrase, or the awful parallel it has come inexorably to imply, when writing his story. But the shape he has given it provides a perfect model of the way inherited guilt can be shifted almost magically onto a faceless foreign scapegoat invented for the occasion. The Greek who in Frisch’s novel appears from nowhere at the last moment to assume the burden of the murderer’s guilt is hidden under multiple anomalies: he is a student in Zurich without knowing German; he is old, he is young; he has no motives, no tangible presence, no connections or relations. He exists simply as a negative neutral Ausländer onto whom Dr. Schaad (whose name implies “harm” or “damage”) off-loads his guilt.

Frisch’s book has been enormously popular in Germany; whether it is being read as a fantasy of being suddenly, magically relieved from guilt or as an indictment of the process of indulging such fantasies, one would have to be a diviner to know. The point is crucial, though the book provoking it is minor. But that Bluebeard has touched many sensitive spots is evident. Outside its particular social setting, one can hardly think it would amount to much. But Frisch’s special gift for enclosing within a frame of deep guilt and shame a lot of vacant and undefined space, into which the reader’s native feelings can insinuate themselves, has clearly dovetailed, in some complex and perhaps duplicitous way, with a historic situation. The book may well prove to have been an important symptom: diagnosticians of the future, with the happy advantage of hindsight, will no doubt tell us what condition it portends in that great, troubled, and now divided nation which is still struggling through nightmares to find its soul.

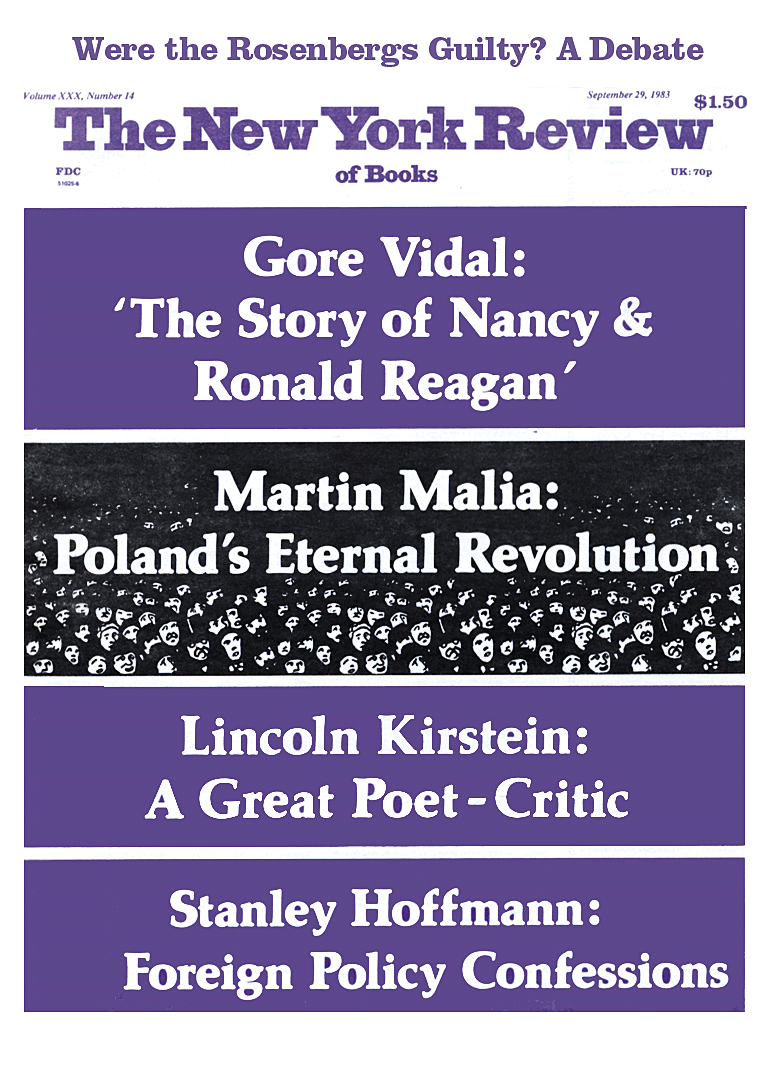

This Issue

September 29, 1983

-

*

Sketchbook 1946-1949 and Sketchbook 1966-1971, translated by Geoffrey Skelton (Harvest/Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983). ↩