“There is no example, no inspiration. It is night. A night of indifference, apathy, chaos.”

So speaks a character in A Minor Apocalypse, first published in Poland four years ago; so might speak a character in almost any other novel coming out of Eastern Europe. Despair is built into the literatures of that part of the world, but since despair, at least of a collective or national kind, cannot be sustained for very long, the question facing both the people and the writers is: What next? We know part of the answer. Most people burrow into privacy, improvising a mixture of withdrawal, opportunism, and small resistance, and hoping, in fundamentally hopeless circumstances, to keep themselves from being eaten away by “indifference, apathy, chaos.”

What writers can make of this situation is one of the more urgent literary problems of our moment. A novelist may show, as Milan Kundera does in The Joke, how the Party dictatorship’s stupidity backfires; he can look with grief, as George Konrad does in The Loser, at the recent history of his country. But after the satire and the indignation have been exhausted there remains the sadness of martyred countries. How is it possible to write about national demoralization without having it seep into the work itself? The creative imagination is likely to find answers that the rational intelligence can’t foresee, but meanwhile, reading a novel like A Minor Apocalypse, one is overcome by the sheer weight of these problems.

Tadeusz Konwicki is an experienced and talented writer. His book came out in Poland just before the upsurge of Solidarity, and to some Polish readers during those great days it must have seemed excessively sour, even defeatist. For despite its bouncy absurdist surface, A Minor Apocalypse is a novel saturated with weariness—weariness with falsity, weariness with having constantly to expose falsity, weariness with continuing nevertheless to live in a world of falsity. Now that Solidarity has been suppressed, Konwicki’s book again seems urgent, perhaps even in some grim sense “vindicated.” “Here comes the end of the world” is its first sentence. Here comes the breakdown of Poland.

The opening chapter is brilliant. A moderately famous writer—let’s call him K.—has been suffering a period of sterility. He gags on bad vodka, bad smells, bad faith. One morning he gets a visit from two representatives of “the opposition.” This is the very day on which the Party is holding its congress, and the porcine first secretary of the fraternal Soviet Party has come to give his blessing in an interminable speech. As a countermove, the opposition proposes that K. set himself on fire in a Warsaw public square. The country needs an extreme gesture to stir people out of lethargy; Warsaw, right now, is “a city of people who are evaporating into nothingness.” And as for the opposition itself, “We’ve grown old, we’ve gone to pot putting out all those semilegal bulletins…which are read by next to no one…. We’ve been overrun by the bourgeoisie, a Soviet bourgeoisie.”

K. decides, out of sheer lassitude and perhaps just a shred of hope, to accept the assignment. After all, why not? He may wonder who in heaven gave these oppositionists the right to make him a present of the death sentence, but about the sentence itself he does not quarrel.

What follows is a string of quasipicaresque adventures leading to the climax of K.’s self-immolation, prefigured but not portrayed. Often with verve but sometimes with a sinking recognition of how futile K.’s act will probably be, indeed how futile it may be even to write about it, Konwicki uses many different modes to recount his experiences: surrealist episodes, brute factuality, high intellectual chatter, malicious epigrams, touches of fantasy, dream sequences, and a lot of rhetoric.

A philosopher explains to K. “the art of allusion,” a subject about which he is soon to lecture at a meeting of the censors: “After a certain amount of time, people will prefer an allusion to the truth itself.” An opposition aide calls to ask K. which color gasoline—he can have red, yellow, or blue—he wants for burning himself alive. A boy, later revealed to be a wreck of forty, follows K., claiming to be a great admirer of his writings and even quoting sententious patches; he is later exposed as a police agent who nevertheless—this being Poland—is a great admirer of K.’s work. A big-breasted Russian girl named Nadezhda, or Hope, turns up, for no discernible reason, in Oppositionist circles to offer K. a few moments of lugubrious love. A former Politburo member offers K. some tidbits of overripe philosophy, though what really interests the old apparatchik is watching a TV program called “The Zoo Show.” A disgruntled Party official tells K.:

Advertisement

“We have demoralized capitalism. Utterly and absolutely. By our own horrible example. We have them so tied up in agreements…that after a while the total socialist chaos we have invented and sustained will bare its teeth even there, among them…. If we don’t overtake capitalism, then capitalism will wait for us.”

K. is held by the secret police for a few hours so that they can inject him with a drug rendering him so sensitive to pain that one flick of a cop’s wrist makes him scream with agony. Later he meets his Russian Hope, and they embrace in an abandoned building—until suddenly a functionary appears to demand 10,000 zlotys. What for?

“For making love in a public building.”

“You mean you can’t do that?”

“You can, but you have to pay.”

“Is it a fine?”

“No, a tax…. You should have come to see me beforehand, I could have loaned you an inflatable mattress.”

The day crumbles into phantasmagoria as K. stumbles across a bonfire in an abandoned lot where some fifteen women are sitting in a circle, “widows, divorcees, old ladies with stormy pasts,” all the women he has loved, abandoned, remembered.

Clever and painfully amusing as many of these episodes are, A Minor Apocalypse seems to me very uneven. Konwicki writes out of a rage that’s probably beyond the ability of any writer to control—the rage of impotence which now and again slips into self-disgust. Witty one-liners and passages are made to do the work that only an integrated narrative structure could. Sometimes, as in Kundera’s fiction, there is a sudden, curious drop into a tone of adolescent silliness, a half-voyeuristic, half-nasty toying with sexuality. At one point K. makes out his last will and testament—a prescription for treating dandruff and a specific for constipation. A culture in which people can’t escape from public falsity must become a culture in which personal relations, even impersonal sensuality, are also contaminated.

The excellent translator Richard Lourie remarks in an introductory note that the book contains some satiric thrusts at Andrzej Wajda, the film director, and Jacek Kuron, the leader of the oppositionist KOR. Wajda is portrayed as a blubbering opportunist: “I can kick the Party in the teeth because I have the right to do it, but I have the right to do it because I have served the Party.” About Kuron, caricatured as an iron-souled ideologue, one of the characters says: “You use the prudent language of a Marxist…. You are just a shadow cabinet of the crew in power.” Whether or not these jibes are warranted an outsider can’t say, but I feel that something is wrong here. Throughout the novel Konwicki seems to be settling personal or factional scores, and when one remembers that Kuron has now been in prison for over a year and still faces the prospect of a trial for his “subversion,” then the effect is decidedly unpleasant.

Two questions remain. If, with all due allowance for the privileges of fiction, the Poland Konwicki draws has any resemblance to the Poland we have recently been watching, then it becomes very hard to account for the upsurge, only a few months after his book’s publication, of the energy and hope embodied in Solidarity. But if nevertheless Konwicki’s bleak sense of things has been vindicated and the Solidarity people shown to be mistaken or naive, then one can only wonder what a novelist can draw upon—what events, themes, voices, tones—in the wretchedness of the Poland that remains.

A Minor Apocalypse can’t, by its very nature, offer answers. But it has its own wracking and bitter authenticity, perhaps most of all when there breaks out a cry we cannot, alas, answer:

“Oh, my brothers, from the forests and the camps, in exile, despair, in this fucked-up life of ours, what should I do?”

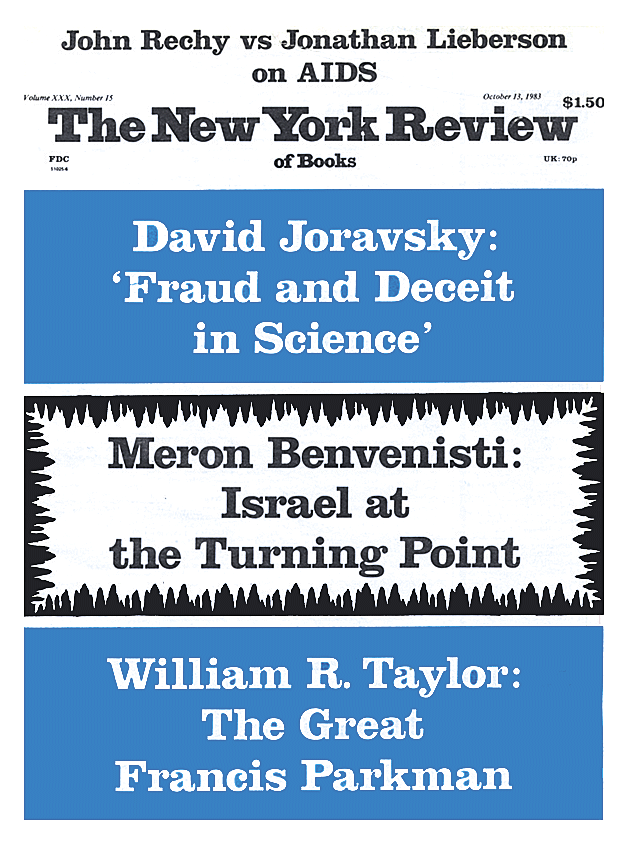

This Issue

October 13, 1983