In response to:

Farewell Buñuel from the November 10, 1983 issue

To the Editors:

Michael Wood’s thorough and intelligent review of Luis Buñuel’s autobiography in the November 10th issue of The New York Review confirms his knowledge and appreciation of his subject. As Buñuel’s translator, however, I would like to clarify my approach to the text, an approach with which Mr. Wood takes issue.

First, Mr. Wood is largely correct in his enumeration of various “elisions, additions, and errors.” The misspelling of Buñuel’s wife’s maiden name (Rucar), for instance, is clearly a typo which was not caught before the book went to press. As for the eighteen films inédits, produced by a careless reading of the verb devoir, I can only blush with embarrassment.

Other “errors,” however, are somewhat more open to debate, given the problems posed by transcription. Mr. Wood objects to my efforts to “smooth out” Buñuel’s “abrupt” thoughts by “broadening his intended effect.” The abruptness of the surrealist voice, image, and poetic as well as political discourse is indeed one of its signal characteristics. I appreciate Mr. Wood’s concern for the loss of this abruptness by the insertion of transitional phrases, but it was certainly not my intention to “put surrealism back in the cupboard of common sense.” There is a necessary distinction between common sense and sense tout court, a distinction between the sudden revelation of thought or image and the fragmentation of a French text haphazardly transcribed from tapes. The French edition demanded certain connectives in the interests of comprehension and accuracy, connections which establish chronology or simply indicate relationship. Without some transitional suggestion, the reader who does not possess Mr. Wood’s expertise might have significant difficulty following the contradictions, digressions, and “leaps” of the surrealist project.

Being of a digressive nature myself, I am particularly sympathetic to Buñuel’s love of the parenthesis, the meander, the haphazard stroll through imperfect memories. But reproducing all digressions, all odds and ends of dimly remembered encounters, from a taped reminiscence is irresponsible. As Buñuel himself cautioned:

Cependant avec l’âge, avec l’affaiblissement inévitable de la mémoire immédiate, antécédente, je dois prendre garde. Je commence une histoire, je l’abandonne aussitôt pour une parenthèse qui me semble très attirante, après quoi j’oublie mon point de départ et je suis perdu. (French text, p. 205)

There are bifurcations and digressions aplenty in the English text—amusing, tender, ironic ones; those that were cut were, in my opinion and in Knopf’s, idle repetitions, lapses in narrative, or simply plots that “got lost.”

As a translator, it would have been tempting to indulge in the fallacy of recreation, to produce a book as surrealistic, in this case, as the life and work of its subject. The French text, however, is scarcely surrealistic. Its inaccuracies and contradictions necessitated hours of research to correct titles, dates, names, etc. And the repetitiousness, despite Buñuel’s fascination with it as technique and tenet, was often due more to neglect and carelessness on the part of French editors than to Buñuel’s taste for oneiric games. (I too appreciate the difficulty Buñuel had in translating images into words.)

In conclusion, I regret that, at least for Mr. Wood, Buñuel’s delicious humor and irony are difficult to discern in my translation. I had hoped to create at least some sense of “the voice we may want to imagine for the author of his films,” as well as to produce a coherent document. I look forward to Mr. Wood’s own study of Buñuel whose publication, I believe, is imminent.

Abigail Israel

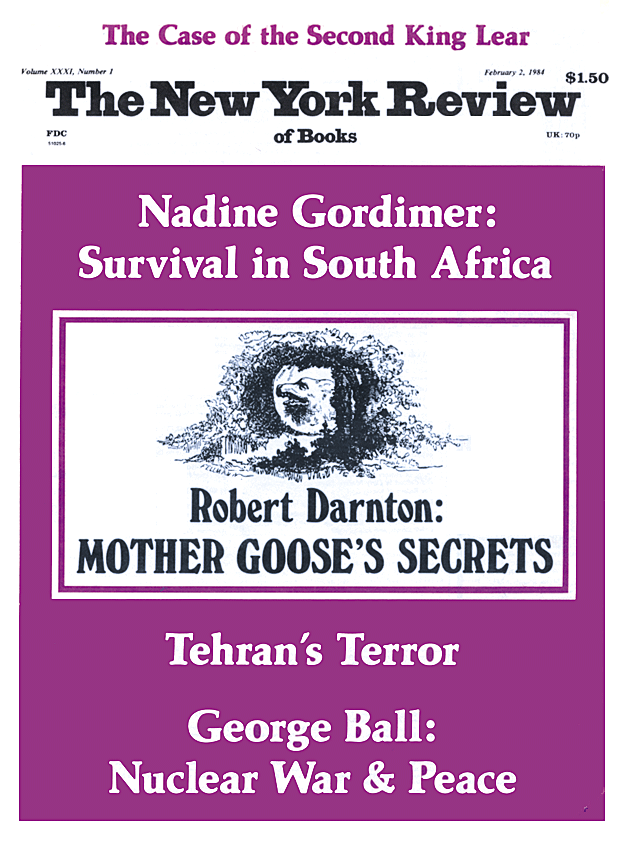

This Issue

February 2, 1984