In response to:

The Evolution of Margaret Mead from the December 6, 1984 issue

To the Editors:

My book Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth was not written as Toulmin supposes out of annoyance at having my work on Samoa “eclipsed” by Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa, nor have I ever been a “colleague or partisan” of Mead’s “embittered second husband,” Reo Fortune.

In fact, when I first arrived in Samoa in 1940 I was a fervent believer in the conclusion Margaret Mead had reached in Coming of Age in Samoa, and it was only after I had observed Samoan behavior at first hand for several years that I was forced to admit—by the evidence I had collected—that her conclusion was at error.

As Mead herself has described, she went to Samoa in 1925 “to carry out the task” which had been given to her by her professor Franz Boas, “to investigate to what extent the storm and stress of adolescence” is “biologically determined and to what extent it is modified by the culture within which adolescents are reared.”

In 1928, in the fourth paragraph of the thirteenth chapter of Coming of Age in Samoa, Mead, with direct reference to this question posed by Boas, came to the conclusion that biological variables are of no significance in the etiology of adolescent behavior; “we cannot,” she asserted, “make any explanations” in terms of the biological process of adolescence itself.

It is specifically with this preposterous conclusion that the refutation contained in my book is concerned. I am here using the word preposterous in its dictionary sense of “contrary to nature, reason or commonsense,” for in the light of modern scientific knowledge, human behavior is, demonstrably, characterized by the interaction of cultural and biological variables, and, as Melvin Konner has recently put it “an analysis of the causes of human nature that tends to ignore either the genes or the environmental factors may be safely discarded.”

As I note in the preface to my book my concern is not with Margaret Mead personally, many of whose achievements I hold “in high regard,” but only with the “scientific import” of her Samoan researches, and my refutation has the explicit objective of correcting the demonstrably mistaken conclusion that many cultural anthropologists and others have long believed to be true.

The making of mistakes is commonplace in science, as, for example, Darwin’s “blunder” (as he called it) over the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy; Freud’s egregious error over sexual seduction in early childhood; and Einstein’s “blunder” (as he also called it) over his “cosmological constant.” It is surely beyond question, however, that if science and scholarship are, in Francis Bacon’s words, to “turn on the poles of truth,” there can within them be no toleration of error.

Is it not time for opponents of my refutation to recognize this and confine their attention to the empirical evidence on which this refutation is based, rather than ridiculously attempting to dismiss me as a dire antipodean dragon, “fueled with accumulated venom,” and intent on “blaspheming one of America’s sacred figures,” for this baseless and irrational ad hominem denigration, even if it were true—which it is not—has no bearing whatsoever on the relevant scientific issues?

Derek Freeman

Research School of Pacific Studies

Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

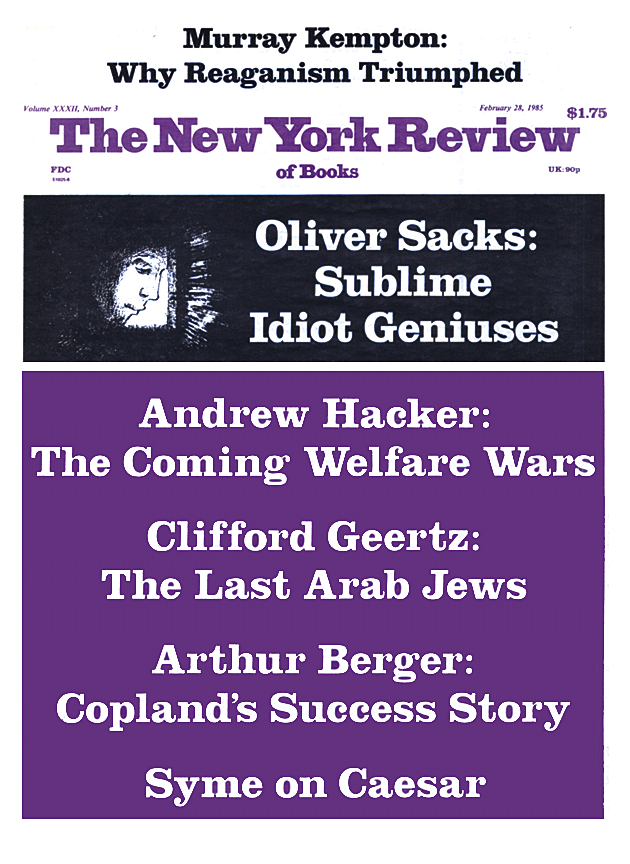

This Issue

February 28, 1985