Calcutta, despite its former resplendence as the first capital of the British Raj, has a dark reputation. One thinks of the Black Hole, or as some Indians prefer to call it, “the alleged Black Hole,” where British ladies and gentlemen died horribly during an uprising led by the nawab of Bengal in 1756. One also thinks of all the travelers’ tales of living corpses gnawed by giant rats right in front of the best hotels; of terrible riots, crippling strikes. Even the goddess after whom the city was named is the most frightful in the Indian pantheon. Kali the Terrible, depicted with a tongue dripping blood and a garland of skulls around her neck is worshiped in Calcutta at a temple next to one of Mother Teresa’s homes for the destitute and around the corner from a filthy stream where corpses decked in flowers are cremated. In front of the temple is a guillotine where goats bought by worshipers are sacrificed to the goddess.

So when an Indian diplomat in Hong Kong said I’d find Calcutta “a friendly sort of place,” I thought he was indulging in some kind of Indian humor. I was too geared up to assume the worst to believe him. And as my plane came to a stand-still at the terminal of Dum Dum Airport (yes, even dumdum bullets were invented in the shadows of Kali) there was a small scene which appeared to confirm my worst expectations. A burly Indian businessman, while chatting to his friend, grabbed his heavy bag from the overhead rack and clumsily, though accidentally, bashed it on the head of the Thai International Airways stewardess. In Thailand the head is believed to contain the soul and being touched—let alone hit—on the head is a grave humiliation. The stewardess was furious and demanded an apology. The Indian did not say a word, he did not even look at the woman, or acknowledge her presence in any way. She was a servant who had stepped out of her role of silent subservience. So she had to be ignored.

In fact, the diplomat in Hong Kong had not been joking. People are remarkably friendly in Calcutta. Just as Kali the Terrible has another identity as a sweet, motherly goddess, Calcutta is not only the “City of Dreadful Night” that Kipling described. Creativity blooms in the midst of poverty and violence, for Calcutta is also a city of poets and dreamers, of splendid though crumbling palaces as well as of ghastly slums. It is telling of the city’s schizophrenic nature that the two most revered Bengalis, endlessly depicted in garish posters sold in the streets, are Rabindranath Tagore, the poet, playwright, novelist, and part-time holy man, and Subhas Chandra Bose, who tried to topple the British Raj by collaborating with Hitler and the Japanese. Tagore was the consummate Bengali Renaissance man, artistic, spiritual, rational, and enlightened. Bose, like many dreamers in the 1930s, had a great fondness for uniforms and violent rhetoric. He looked a bit like a pudgier and swarthier version of Heinrich Himmler. He was more popular in Bengal than Mahatma Gandhi.

Still, despite the sweet and elegant side of Calcutta, the incident in the plane was not an isolated one. As it does everywhere else in India, behavior in Calcutta depends to a very large extent on the social roles people play. These are shaped by class, caste, religion, native language, and all the other myriad divisions that put a social tag on almost every Indian. The divisions are quite concrete. Every community lives within invisible walls, which individual members carry with them wherever they go. The Canadian novelist Bharati Mukherjee described this when she returned for a year to her native city: “Calcutta seemed to me to be made up of separate walled villages between which there was only defective communication.”1 Her husband, Clark Blaise, wrote in the same book that he was the first person to find out the full names of the servants working for and living at close quarters with his parents-in-law in Bombay. It simply would not have occurred to his father-in-law to ask. It is as if Indians deal with the potentially explosive problem of communities ranging from the obscenely rich to garbage eaters living virtually on top of one another by cloaking themselves in ignorance, by pretending not to see.

The extreme and dramatically visible poverty in Calcutta is nevertheless hard to ignore, even for many Indians who should be inured to it. Some, especially those with a Western education, feel a vague sense of guilt. “It is really a criminal act to own these things,” said an advertising executive, pointing at the new video machine in her elegant and spacious apartment. It is certainly a challenge to the liberal conscience to see two men literally fighting over the job of guarding one’s shoes to earn less than a cent at the entrance of the Kali temple. One can be outraged at society and dispense a small fortune to the mutilated children tugging one’s sleeve. But that won’t help much. One can opt for a Marxist revolution, as many artists and intellectuals do, or at least for a communist state government like the one that rules West Bengal today. That does not seem to help a great deal either. The sense of helplessness, even hopelessness, is made worse, in a way, by the fact that the Indian press is among the freest in the world; all India’s problems are faithfully reported every day, but nothing much changes.

Advertisement

Perhaps the strongest temptation, if only for one’s own peace of mind, is to accept human degradation as being somehow in the natural order of things. If I can sit in an air-conditioned restaurant tucking into a lunch that could feed the family sifting through a pile of refuse outside for a week, well, that must be the way the gods arranged the world and who am I to question it? All one can do is pray to the gods, sacrifice a goat, or at least donate some money to Mother Teresa, who is a kind of deity in Calcutta anyway.

The next step is to suggest that the poor do not mind their plight. An intelligent and liberal-minded Bengali journalist explained to me that a certain left-wing film maker was quite wrong in his depiction of the poor in Calcutta. “He is from the upper class and does not understand these people. From his point of view they may seem miserable, but in fact they are quite happy people. They may only eat once a day, but they don’t really want more.” The final step along this road is to pretend that poverty is spiritually uplifting, that the garbage eater is somehow a richer man than I. Imelda Marcos, when she still reigned, used to hold up her poor “little people” as examples of higher Philippine spirituality because they smiled while going hungry.

This appears to be closest to Dominique Lapierre’s position in his (the jacket copy tells us) “epic of love, heroism, and hope in the India of Mother Teresa.” Lapierre is a French journalist with an enviable knack for writing best sellers about subjects ranging from the almost burning of Paris by Hitler to the Independence of India in 1947. The City of Joy is a catchy title, but seems an odd name for the worst slum in a city of slums. It was not invented by Lapierre, but by a jute-factory owner who housed his workers there at the beginning of the century. This is how Lapierre describes the place:

It had the densest concentration of humanity on this planet, two hundred thousand people per square mile. It was a place where…children did not even know what a bush, a forest, or a pond was, where the air was so ladened with carbon dioxide and sulphur that pollution killed at least one member in every family; a place where men and beasts baked in a furnace for the eight months of summer until the monsoon transformed their alleyways and shacks into lakes of mud and excrement; a place where leprosy, tuberculosis, dysentery and all the malnutrition diseases, until recently, reduced the average life expectancy to one of the lowest in the world.

But it is an unusual slum, reflecting perhaps both the dark and the good side of Calcutta, for here

people actually put love and mutual support into practice. They knew how to be tolerant of all creeds and castes, how to give respect to a stranger, how to show charity toward beggars, cripples, lepers, and even the insane. Here the weak were helped, not trampled upon. Orphans were instantly adopted by their neighbors and old people were cared for and revered by their children.

Lapierre (again according to the jacket) “immersed himself for months in its awesome reality,” so we must take his word for it. By surviving their misery with smiles and human kindness, so Lapierre would have us believe, the denizens of the City of Joy offer us, selfish consumers of the Me Decade, a lesson in hope.

It is a useful lesson but a slightly too comfortable one, for, according to Lapierre, in an article in the French magazine Le Débat on how he writes best sellers, the poor of the City of Joy do more than survive with a smile: “I found [there] more heroism, more love, more sharing, and finally more happiness than in many of the cities in our wealthy West.”2 Here is a fine recipe for a best seller in the wealthy cities in the West. What is the cliché of all sentimental novelettes and gossip magazines for the masses? That the rich and famous are actually deeply unhappy. How nice it is to know for us rich Westerners that the poorest people of Asia are actually very happy. This makes us all feel happy. And nobody can be happier than the bearer of the good news who makes himself a fortune in the process.

Advertisement

For those interested in writing best sellers too (who is not?), it is interesting to know what else Lapierre has to say about his craft. First, he says (in the same issue of Le Débat), you need a good subject. “But above all the author must be in love with his subject. I was in love with Paris, Spain, Jerusalem, India, the New York of The Fifth Horseman. I am at present in love with the City of Joy. It is true: every one of my books is a story of love.” It is well known from the same novelettes about unhappy rich people that love is blind, or at least makes one blind. The least one can say is that rapture and common sense are unhappy bedfellows.

The next ingredient in the perfect Lapierre best seller, says the author, is the interview. “The subject must lend itself to the interview technique. We are journalists by training. Our real force de frappe is the interview.” This is evident in the book at hand. Lapierre tells much of his story through interviews, by using direct quotes from his main characters, who include a Polish-born French priest, a young Jewish doctor from Florida, an angelic young woman from Assam, and a rickshaw puller from rural Bengal. Sometimes we are even told what people thought, in quotation marks—just how the author knew what they thought is a bit of a mystery. Quotes translated from Indian languages to French are not always rendered adequately in English: it is difficult, for example, to imagine an Indian procurer of a blood bank saying, “Holy mackerel! That bum can’t even count up to seven.”

Lapierre’s prose has an overblown quality about it, a bit like an epic Hollywood movie, or more to the point, Paris Match journalism. This results in some entertaining scenes, like a description of a drunken leper wedding when

those lepers who still had limbs leaped to their feet and began to dance. Stumps joined stumps in a frenzied farandole that snaked its way around the courtyard to the laughter and cheers of all the others present.

He is also very good at describing squalor, as at the City Hospital, where the French priest, called Kovalski, is brought after catching cholera:

Wherever you went you found yourself treading on some form of debris. Worst of all, however, were the people who haunted the place. The severely ill—suffering from encephalitis, coronary thrombosis, tetanus, typhoid, typhus, cholera, infected abscesses, people who had been injured, undergone amputations, or been burned—were lying all over, often on the bare floor…. At the end of the corridor were the latrines. The door had been torn off and the drain was blocked. Excrement had spilled over and spread into the corridor, much to the delight of the flies.

The fondness for high drama can be disastrous, too. The young American doctor, called Max Loeb, gets tired of the City of Joy after almost drowning in a cesspool. For rest and recreation he has a fling with Manubaï, a rich Calcutta socialite: “Having danced a few steps, the Indian woman and the American had drifted gently toward the soft cushions and silken sheets of the four-poster bed.” It is a scene straight from the script of Emmanuelle, made in India.

One wonders whether, despite the interviews and the research, things really happened quite this way. These doubts are strengthened by the information in the preface that “I have purposely changed the identities of some characters and certain situations.” Which characters, which situations?

As one reads on, from one bizarre scene to the next, without respite, without pause for the more banal aspects of daily life, the feeling grows that Lapierre’s book is not so much a document as an artistic vision, of sorts; a vision based on the careful selection of facts. It is a peculiarly Victorian vision, a mixture of Gustave Doré’s prints of London slums and the sanctification of Florence Nightingale. Lapierre is a bit like Dickens, the fascinated observer of misery and the sentimental propagandist for Christian charity. Victorian charity was a way of finding God.

The characters of both Kovalski and Loeb invite the Western reader to identify not with Indian reality, but with India as a spiritual experience—the sort of thing middle-class hippies sought in the olden days when George Harrison played the sitar, and panhandling was considered a worthy protest against the materialist values of mom and dad. As a result of this technique the Western characters who have chosen to immerse themselves in the Indian slum for completely personal reasons become the center of our attention. The book is really about them, not about the unfortunate Indians who live in squalor because they have no other choice.

Living in the lower depths was part of Kovalski’s religious quest. “Yes, it was definitely to this slum at the far corner of the world that his God had sent him,” writes Lapierre. “My enthusiasm and yearning to share had been right to push me into embarking on an experience considered impossible for a Westerner. I was so deliriously happy, I could have walked barefoot over hot coals,” says Kovalski. Once established in the slum he begins to sound more like Allen Ginsberg than Florence Nightingale:

That night, as I repeated the Oms that came from the other side of the street, I experienced the sensation not only of speaking to God but also of taking a step forward into the inner mystery of Hinduism, something which was very important in helping me to grasp the real reasons for my presence in that slum.

Finally, after comparing the City of Joy to Bethlehem, the priest concludes that “it is easy for any man to recognize and glorify the riches of the world…. But only a poor man can know the riches of poverty. Only a poor man can know the riches of suffering.” Mrs. Marcos could not have put it better.

Having said this, I feel guilty already, for the priest, despite his absurd talk, does undeniable good; unlike my squeamish self, he does go out and help lepers. Being snide about Kovalski is like attacking Mother Teresa or Bob Geldof, or indeed Florence Nightingale. Saints are above criticism and, according to Lapierre, Calcutta “has the magical power to create saints.” The problem with saints is that they lack the power to solve problems of the magnitude of India’s poverty. They can only bring relief, to some of the poor themselves, but especially to all the rest of us who can rest assured that at least something is being done, preferably in our name, after donating some pocket money. “Mother Teresa makes us feel good,” said one rich and candid Calcutta businessman when I asked him what he thought of her work.

This is why Lapierre’s latest best seller is such a clever book. While the reader is being titillated no end by spectacular descriptions of the City of Dreadful Night—which is always fascinating, especially to the French with their nostalgie de la boue—he is at the same time made to feel virtuous, or at least not guilty about the kind of literary Schadenfreude to be derived from this book. Misery in a Calcutta slum is not simply exciting or exotic in a romantic nineteenth-century kind of way, but “moving,” even uplifting. To make sure we do not mistake Lapierre’s breathless prose for aesthetic slumming, there is a picture of the author with Mother Teresa on the back cover. She hardly figures in the book at all, but Lapierre establishes his moral credentials this way. And to make absolutely sure that God is on Lapierre’s side, we are told that “a portion of the proceeds from the sale of this book will go toward helping the author’s friends in the City of Joy.” He has, he tells us in Le Débat, raised funds for a shelter there as well.

There is certainly nothing wrong with good deeds and helping others. It would also be priggish to attack an artist for transforming human misery into a vision of beauty, or a journalist for turning horror into a good story. Nor is there anything against writing a best seller and making a lot of money. What leaves a bad taste is the wrong combination of big bucks and high virtuousness, especially when the latter appears to be put in the service of the former. That is why, after reading this book, I was not really moved, as no doubt I should have been, given the nature of the subject. Instead I felt uneasy, like watching a striptease show at a Salvation Army mission without knowing whether the money goes to the pimp or to the poor.

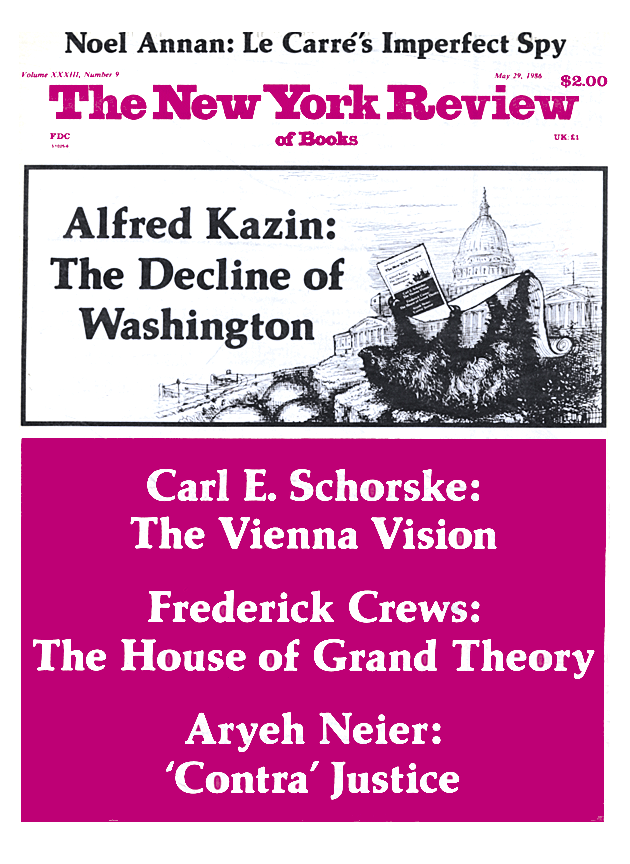

This Issue

May 29, 1986