for Donald Richie

IMAGINING IT

Paul phones to say goodbye. He’s back in New York two days early, but we are tied to our trip—departure this evening—and he, for his part, doesn’t ask us over. (Can a single week have changed him? Surely not.) Our dear one sounded strong, unconcerned, above all glad to have left the Clinic. Famous and vast and complex as an ocean liner, it catered chiefly to elderly couples from the Plains. Whether both were ill, or just the husband or the wife, they’d chosen not to be separated. They slept (as did Paul) at the nearby hotel, then spent their waking hours together in lounges, the magazine unread, or strolling hand in hand the gleaming, scentless corridors from one test to the next. Paul, though, was by himself, was perhaps not even “sailing.” Waiting to hear over his own system the stern voice calling Visitors ashore! he would have begun to feel that—aside from the far too young and noncomittal crew—bona fide passengers only were expected to circulate there, all in the same boat, their common dread kept under wraps, yet each of them visibly

at Sea. Yes, yes, these

old folks grown unpresuming,

almost Japanese,had embarked too soon

—Bon voyage! Write!—upon their

final honeymoon.

ARRIVAL IN TOKYO

Our section of town is Roppongi, where thirty years ago I dined in W’s gloomy wooden farmhouse. The lanes and gardens of his neighborhood have given way to glitzy skyscrapers like this hotel—all crystal and brass, a piano and life-size ceramic Saint Bernard in the carpeted lobby. It is late when the revolving door whisks us forth, later yet when our two lengthening shadows leave the noodle shop to wander before bed through the Aoyama cemetery. Mishima is buried down one of its paths bordered by cherry trees in full, amazing bloom. Underneath, sitting on the ground—no, on outspread plastic or paper, shoes left in pairs alongside these instant “rooms”—a few ghostly parties are still eating and drinking, lit by small flames. One group has a transistor, another makes its own music, clapping hands and singing. Their lantern faces glow in the half-dark’s black-beamed, blossom-tented

dusk within the night.

The high street lamp through snowy

branches burns moon-bright.

DONALD’S NEIGHBORHOOD

Narrow streets, lined with pots: wistaria, clematis, bamboo. (Can that be syringa—with red blossoms?) Shrines begin. A shopkeeper says good day. Three flights up in the one ugly building for blocks around, Donald welcomes us to his bit of our planet. Two midget rooms, utilitarian alcoves, no trace of clutter. What he has is what you see, and it includes the resolve to get rid of things already absorbed. Books, records. His lovers he keeps, but as friends—friends take up no space. He now paints at night. Some canvases big as get-well cards occupy a wall. Before we leave he will give the nicest of these to Peter.

What are we seeing? Homages to Gris, Cornell, Hokusai, Maxfield Parrish. Three masters of compression and one of maple syrup. Without their example, where mightn’t his own work have gone? (Would he have painted at all?) As for his album of lovers, without the archetypal Uncle Kenny to seek throughout the world, who mightn’t he have loved? And what if he hadn’t settled in Japan forty years ago? Living here has skimmed from his features the free-floating self-pity, cynicism, and greed of his doppelgänger in that all too imaginable jolly corner of Ohio.

Later—stopping first at a bookstore to buy what they have of Donald’s in stock—we proceed to the projection room, where at our instigation we are to be shown six of his films. No clutter about them either. The program is over in just ninety minutes. What have we seen?

Boy maybe eighteen

bent over snapshots while his

cat licks itself clean.Naked girl, leading

suitors a merry chase: she’ll

leave them stripped, bleeding—

this last to courtly music by Rameau. And finally

a dead youth. The shore’s

gray, smooth, chill curve. His flesh a

single fly explores.

STRATEGIES

Halfway around the globe from Paul the worst keeps dawning on us. We try to conjure him up as he was only last winter: hair silvered early, the trustful, inquisitive, nearsighted face, the laugh one went to such lengths to hear. His book was practically done, he’d quit biting his nails. Well, now he knows, as do we; and the date line, like a great plate-glass revolving door, or the next six-foot wave in an epic poem, comes flashing up to face the music. I need a form of conscious evasion, that at best permits odd moments when the subject

looking elsewhere strays

into a local muse’s

number-benumbed gaze

—fixed there, ticking off syllables, until she blinks and the wave breaks. Coming to, once again drenched, a fugitive, one is after all saner for the quarter-hour spent as a splotch of lichen upon that quaintest of steppingstones.

Advertisement

Don’t worry, I’m getting my share of fast food, TV news and tearjerkers, police running toward the explosion, our sickeningly clear connections to New York, a boîte called Wet Dream, the taximeter advancing, like history itself, by life spans: 1880 to 1950 to 2020. Yet this Japan of tomorrow tends chiefly to mirror and amplify a thousandfold the writhing vocalist in my own red boîte, whom I want gagged, unplugged, short-circuited. If every trip is an incarnation in miniature, let this be the one in which to arrange myself like flowers. Aim at composure like the target a Zen archer sees through shut eyes. Close my borders to foreign devils. Take for model a cone of snow with fire in its bowels.

KYOTO

Daybreak. Brightest air

left brighter yet by hairline

cracks of gossamer.

Temple pond—work of a mad priest who thought he was a beaver? In the foreground roots scrawl their plea for clemency upon a golden velvet scroll. Granted, breathe the myriad starlets of moss, the dwarf maple’s inch-wide asterisks. The dead stump is tended as if it had never been more alive. “To die without assurance of a cult was the supreme calamity.” (L. Hearn)

RIVER TRIP

Short walk through fields to soft-drink stand where boats wait—all abroad! Creak of rope oarlock. One man pulls the single oar, another poles, a third steers, a fourth stands by to relieve the first. Highup shrine, bamboo glade. Woodland a cherry tree still in bloom punctuates like gunsmoke. Egret flying upstream, neck cocked. Entering the (very gentle) rapids everyone gasps with pleasure. The little waves break backwards, nostalgia conmoto, a drop of fresh water thrills the cheek. And then? Woodland, bamboo glade, high-up shrine. Years of this have tanned and shriveled the boatmen. For after all, the truly exhilarating bits

were few, far between

—rocks pole-goaded past, dumb beasts

mantled in glass-greengush—and patently

led where but to the landing,

the bridge, the crowds. We

step ashore, in our clumsiness hoping not to spill these brief impressions.

AFTERNOONS AT THE NOH

Plays of unself. Peel off the maiden pearl-diver to find her mother’s ghost, the ghost to wake a dragon who, at the end of his dance, will attain Buddhahood. Masked as each of these in turn, the protagonist has the wattles and frame of

a middle-aged man—

but time, gender, self are laws

waived by his gold fan.

Often depicted are the sufferings of poor people—woodcutters and fishermen, who nonetheless appear in uncommon finery. They’ve earned it. Each has entered the realm of legend and artifice, to become “a something else thereby.” What glides before us is the ectoplasm of plot.

Enter today’s ghost. Masked, longhaired and lacquer-bonneted, over his coral robe and white trousers he wears a coat of stiff apple-green gauze threaded with golden mazes. In life he was the warrior prince Tsunemasa. Before long, stirred by a votive lute we don’t hear, he will relive moonlight, storm and battle, and withdraw, having danced himself to peace. At present the stage picture is static, a problem in chess. The eight-pawn chorus is chanting in antiphon with Tsunemasa—a droning, fluctuating,

slowly-swelling hymn:

the god’s fingertip circling

one deep vessel’s rim

after another, until all the voices are attuned.

The drummer with a thimbled fingertap neat as a pool shot cuts short the vocalise he at once resumes: a guttural growl that ends falsetto, hollow pearl balanced upon a jet of water,

full moon kept at bay

above Death Valley by the

coyote roundelay.

The music has no purpose, Professor Shimura insists, but to mark time for the actors. Blindfolded by their masks, oriented, if at all, by the peripheral pine tree or stage pillar, they need whatever help they can get. (Then why this music, so animal, so ghostly?)

Feet in white socks explore the stage like palms of a blind man. When they stamp it is apt to be without impact, the dancer having levitated unawares. Hands are held relaxed but gravely furled. Middle knuckles aligned with thumb unbent compose half a right angle. Into the hollow that results may be set a fan or willow-branch. Nothing easier than to withdraw it. Hands like these will never clench or cling or stupidly dangle or helplessly be wrung. They are princes to be served and defended with one’s life. My own hand as I write, wielding this punctilious lance of blue, belongs to a lower caste.

Advertisement

A story Paul heard from an old surrealist in Pau:

The Emperor’s boyhood friend was convicted of treason and sentenced to death by decapitation. In honor of their former intimacy, the Emperor ordered the execution before dawn, after a banquet for his friend at which the Court dancers would appear. That legendary troupe could perform anything: the Spider Web, A Storm at Sea, the Nuptials of the Phoenix. On this occasion they outdid themselves. Yet well before the stars had set, the doomed man turned to his host: “The Son of Heaven has shown unmerited consideration, but really, can’t we call it a night and conclude our business without further ado?” The Emperor raised his eyebrows: “My poor friend,” he smiled, “haven’t you understood? Your head was cut off an hour ago.”

Oki Islands, a week later, after dinner. The maid, miming anticipation, slides open doors onto a little scrim of pine trees flat and black against the dazzle.

Waves whisper. Tonight

the netmender’s deaf son reads

their lips by moonlight,

but the real drama is due to go on elsewhere. Already owls and crickets are studying the program in silence. Long minutes pass. Imperceptibly the moon’s ripeness comes to us bruised by some imminent “shadow of a thought.” A dark thought that fills the psyche, leaving a bare brilliant cuticle, then nothing, a sucked breath, a pall. The stars crowd forward, like wizards round a sickbed. The goddess has donned her

brownest mask: malign

pomegranate or somber

ember—muss es sein?

Not this time. Watch:

Minim by scruple the high renaissance….

Celestial recovery. Altogether grander and more mysterious than anything at the Noh, yet from what lesser theater did we absorb the patience and piety needed to bring the moonlight back?

DOZEN

Circling the island. Fantastic volcanic forms, dragon-coil outcrops nostril-deep in clear water—or so it might have been. But this stormy noon we’re alone in the boat, screens of mist enfold the heights, and the famous drowned savannas, green-gold or violet-pink in travel posters, come through as dim, split-second exposures during which

one seaweed fan waves

at another just under

from above the waves.

KYOGEN INTERLUDE: AT THE BANK

It is by now clear that the poor flushed clerk—a trainee’s badge on his lapel—knows nothing. Fifty minutes have passed, our traveler’s checks are still being processed, and we have missed our train to Koyasan.

Donald (at the counter, smiling gleefully): Excuse me, would you kindly ask your supervisor to step this way?

Clerk (in sudden English): No. Please, he. Today not here.

Donald (still in Japanese): Nonsense. It’s Monday morning. Everyone’s here.

Clerk: I. No. He.

Donald: Because if you do not fetch him I shall be obliged to go and ask for him myself.

The clerk pales and vanishes, returning accompanied by an older man in neat shirtsleeves—the supervisor—who asks how he can be of service.

Donald: Good morning. My name is R—. I am a writer and journalist living in Tokyo. Allow me to give you my card.

Manners require that a card be studied by its recipient with every show of genuine interest. The supervisor beautifully clears this first hurdle. Donald resumes. During his tirade his listener’s breathing quickens, his eyes glitter. He and the red-faced clerk, side by side, are contemplating the abyss to whose brink we’ve led them. The younger man, slightly bent, hands clasped at his crotch, has braced himself like one about to be flogged.

Donald:…and furthermore I shall speak of this on my return to Tokyo.

Supervisor (face carefully averted from the culprit): See here, you’ve been trained. Are you still incapable of a simple transaction? Then find someone in the office to take over. This is Osaka, not your village. I hold you responsible for a great rudeness to these distinguished guests.

To every phrase the clerk winces assent. Trays of clean money appear, which having pocketed we take our leave.

Supervisor (bowing us to the door): There is no apology for such a mortifying affair.

Donald: Please, it is of no consequence. I mentioned it only to spare your bank any future embarrassment.

JM (on the eventual slower train): Will you really make a fuss in Tokyo?

Donald: Goodness, no. What do you take me for?

Eleanor (hearing it told months later): Yes, that’s what Mother used to call The Scene. As a child I watched her make it all over the world. You begin by saying you’re an intellectual. It strikes the fear of God into them, I can’t think why. Not here in America, of course, but anywhere else—! How do you think I got on that air-conditioned bus in Peru? How do you think I got out of East Berlin that ghastly Christmas? I told them I was a writer and journalist. I made The Scene.

DJ (amused in spite of himself): That story wasn’t nice. Even bank clerks have to live.

Eleanor: Darling boy, nobody has to live. It’s what I came away from Paul’s service thinking. Nobody has to live.

SANCTUM

Another proscenium. At its threshold we sit on our heels, the only audience. Pure bell notes, rosaries rattled like dice before the throw. Some young priests—the same who received us yesterday, showed us to our rooms, served our meal, woke us in time for these matins—surround a candle-lit bower of bliss. The abbot briskly enters, takes his place, and leads them in deep, monotonous chant. His well-fed back is to us. He faces a small gold pagoda flanked by big gold lotus trees overhung by tinkling pendants of gold. Do such arrangements please a blackened image deep within? To us they look like Odette’s first drawing room (before Swann takes charge of her taste) lit up for a party, or the Maison Dorée he imagines as the scene of her infidelities. Still, when the abbot turns, and with a gesture invites us to place incense upon the brazier already full of warm, fragrant ash, someone—myself perhaps—tries vainly

to hold back a queer

sob. Inhaling the holy

smoke, praying for dear

life—

PUPPET THEATER

The very river has stopped during Koganosuke’s dialogue with his father. All at once—heavens!—the young man takes up a sword and plunges it into his vitals. There is no blood. He cannot die. The act will end with his convulsive efforts to. Meanwhile the rapids that divide him from his beloved begin to flow again—blue-and-white cardboard waves jiggled up and down—so that the lacquer box containing her head may be floated across to where he quakes, upheld by three mortals in black.

(Into the Sound, Paul,

we’d empty your own box, just

as black, just as small.)

The lovers neither spoke nor acted—how could they? Their words came from the joruri, or reciter, who shares with the samisen player a dais at the edge of the stage. Upon taking his place the joruri performs an obeisance, lifting the text reverently to his brow. It is a specialized art—what art is not?—and he glories in it. He has mastered Koganosuke’s noble accents, the heroine’s mewing, and the evil warlord’s belly laugh which goes on for minutes and brings down the house. To function properly each puppet requires three manipulators. These, with the joruri, are the flesh and blood of this National Theater, and come to stand for—stand in for—the overruling passions, the social or genetic imperatives, that propel a given character. Seldom do we the living, for that matter, feel more “ourselves” than when spoken through, or motivated, by “invisible” forces such as these. It is especially true if, like a puppet overcome by woe, we also appear to be struggling free of them. (Lesser personages make do with two manipulators, or only one.)

“…wonderful today…!”

you yawned that night. It moved me:

words began to play

like a fountain deep

in gloom. Did love reach out your

arm then? Sorrow? Sleep?

GEIGER COUNTER

Pictures on a wall:

a View of Fuji challenged

by The Dying Gaul.Syringe in bloom. Bud

drawn up through a stainless stem—

O perilous blood!Tests, cultures…Weeks from

one to the next. That outer

rim of the maelstromhardly moved. Its core

at nightmare speed churned onward,

a devolving roar:Awake—who? why here?

what room was this?—till habit

shaded the lit fear.

“You’re not dying! You’ve been reading too much Proust, that’s all! I could be dying too—have you thought of that, JM?—except that I don’t happen to be sick, and neither do you. What we are suffering are sympathetic aches and pains. Guilt, if you like, over staying alive. Four friends have died since December, now Paul’s back at the Clinic. You were right,”—the dying Paul, what else?—“we should have scrapped the trip as soon as we heard. But God! even if you and I were on the way out, wouldn’t we still fight to live a bit first, fully and joyously?”

Such good sense. I want to bow, touch my forehead to the straw mat. Instead: “Fight? Like this morning? We can live or die without another of those, thank you.” Mutual glares.

The prevailing light in this “Hiroshima” of trivial symptoms and empty forebodings is neither sunrise nor moonglow but rays that promptly undo whatever enters their path. They strip the garden to clawed sand. They whip the modern hotel room back into fatal shape: the proportions and elisions of centuries. In their haste to photograph Truth they eat through a blue-and-white cotton robe, barely pausing to burn its pattern onto the body shocked awake.

“What’s the story, Doc?”

—dark, cloud-chambered negatives

held to the light. Knock,

knock. Not dinnertime already? Donald, making his ghoul face, joins us for another feast less of real food than of artfully balanced hues and textures. “I’m sick,” sighs the sunburnt maid who serves it, and whose kimono we think to please her by admiring, “sick of wrapping myself up like a dummy day after day.” Has the radiation affected her, too? And what about this morning’s blinding outburst?

ANOTHER CEMETERY

We pass it on our descent from the temple. The gravestones are vertically incised with the deceased’s new name, the name assumed after death. Only by knowing it can a friend or kinsman hope to locate one’s tomb among so many others. They all—untapering stone shafts on broad plinths—look exactly like scale models for skyscrapers in the 1930s. Intelligent intervals separate them. Light and air will have been of prime importance to whoever planned this “city of tomorrow,” its little malls and avenues half-lost in foliage, and took care to place its ugly realities out of sight. In today’s cold drizzle we feel he was not wholly successful. Oh for a glowing hearth to come home to!—as another name sputters, a

last flickering shift

of flame flutters off. The log’s

charred forked shape is left.

(Sold up at the temple, distant cousin to both the gravestone and the “Plant-Tab” stuck in a flowerpot to release nutrients over weeks to come: the incense stick. This brittle, narrow slab of dark green, set upright in the burner’s ashheap and lit, will also turn to ash. But in the process, as it whitens, a hitherto unseen character appears, below it a second, slowly a third, each traced by the finest penpoint of incandescence. They cool the way ink dries. Once complete and legible, their pious formula can be scattered by a touch. Any fragrance meanwhile eludes me. Have I caught cold?)

IN THE SHOP

Out came the most fabulous kimono of all: dark, dark purple traversed by a winding, starry path. To what function, dear heart, could it possibly be worn by the likes of—

Hush. Give me your hand. Our trip has ended, our quarrel was made up. Why couldn’t the rest be?

Dyeing. A homophone deepens the trope. Surrendering to Earth’s colors, shall we not be Earth before we know it? Venerated therefore is the skill which, prior to immersion, inflicts upon a sacrificial length of crêpe de Chine certain intricate knottings no dye can touch. So that one fine day, painstakingly unbound, this terminal gooseflesh, the fable’s whole eccentric

star-puckered moral—

white, never-to-blossom buds

of the mountain laurel—

may be read as having emerged triumphant from the vats of night.

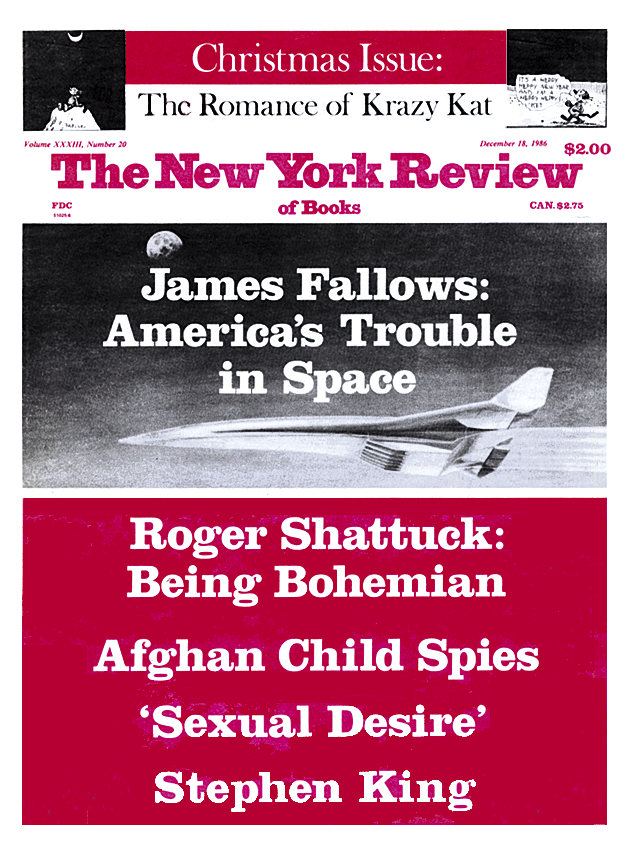

This Issue

December 18, 1986