One comes to Nadine Gordimer’s new novel, A Sport of Nature, conscious of a certain critical division about it. On the one hand it is called by Maureen Howard in The New York Times Book Review “the perfect equation” between talent and experience, a grand act of the imagination. On the other hand, to Jennifer Krauss in The New Republic it is a “deeply cynical novel” in the realm of “popular, blockbuster, Book-of-the-Month Club fiction,” and to Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times a “glib encapsulation of recent history” whose form has something in common with Judith Krantz or Sidney Sheldon. Indeed the tone of the novel is elusive, the narrative method susceptible to either interpretation.

To this reader, it seems to boil down to how much credit Gordimer has built up for the vigor and courage of her antiapartheid politics over the years, and the beauty and power of much of her other recent writing, for this book seems compounded of mythic and modernist elements too resistant quite to work as a novel. It may be that an American reader, owing to the different rhythms of his history, has certain disadvantages. Since there is no defense on apartheid, it can seem that something obvious is being advanced with great righteousness here. In another Gordimer novel, Burger’s Daughter, someone says, “Yes, it’s strange to live in a country where there are still heroes.” What that’s like is something hard for an American to remember. The South African world, in its turmoil, in the accelerating pace of its changes, has, perhaps, a greater need for saints’ legends and inspirational fairy tales, while the disaffected American can no longer believe in them.

Gone is the spare, meditated manner of July’s People; here Gordimer returns to certain themes and episodes found in her earliest, seemingly autobiographical, and often somewhat tendentious works, fitting them almost at random into a romantic political newsreel. No doubt there are moments in history when the idea of art for art’s sake is offensive; that old debate has ever only arisen in those moments of calm between wars. Liking it or not, Gordimer was born into interesting times, and has reported and judged them. Twenty-five years ago, in The Late Bourgeois World and A Guest of Honour, Gordimer captured the secret meetings, the clandestine intrigues, the secret dreams of the politically forward-thinking. She has pointed out that the voice of a “politically devout” life is always addressing “the human mass.” Her early work was reminiscent of old Marxist novels reset (quotations from Fanon and so on—the sort of novels the heroine in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook doesn’t want to write).

But in her finest work—her superb short stories, for instance—Gordimer’s polemics are only implicit, and her ability vividly to present people caught in the moral dilemmas and actual peril of a foundering society is consummate and, we are bound to feel, so correct that what it lacks in charm and humor—there are no jokes in Gordimer, anywhere—is more than made up for by her powerful descriptive language, her passion, an impressive ability to put herself not only in the mind but in the body of anybody, male or female, black or white, and a sort of supercharged landscape that simultaneously operates as the beautiful natural world and the arid metaphoric country of the blighted South African soul. Even if Gordimer were not a wonderful writer, the setting and subject of her stories are themselves so interesting and exotic that we would be drawn to her work. South African sins are not (we tell ourselves) ours, and the heroism of people under oppression, or caught in forbidden interracial love, is so much more stirring than marital discontent on Central Park West.

In this new book, with the world catching up to, or on to, the events that Gordimer has been explicitly predicting for thirty years, one senses a rush to the dais. Narrative founders under the double burden of prediction and justification, and under the weight of reality, and under the weight of a prophet’s hard-earned crown. A friend once remarked, speaking of his admiration for Gordimer’s novels, that they were so good he didn’t actually bother to read them. One senses, embedded in this apparent paradox, an elusive but eternal literary fact. But what is it? Perhaps it is that readers in some way wish a writer to affirm his humanity by making a mistake, if it is a small one. One felt, say in July’s People, or The Conservationist, with something like the perfect combination of narrative interest, rich, accomplished language, high moral seriousness, round characters, and so on, that there were no mistakes. There is, at least, something urgent and appealing in this riskier, less successful work.

Advertisement

A Sport of Nature (the title refers to the heroine) is the picaresque tale of Hillela (named after her Jewish grandfather), who, after her mother runs off with a Portuguese lover, is raised by her aunts Olga (refinement and bourgeois comfort) and Pauline (middle-class liberalism). After she’s thrown out for sleeping with her cousin, Pauline’s son, she moves on to a series of jobs—receptionist, encyclopedia salesman, political activist helpful with making coffee and Xeroxes. Somewhere along the way she takes up with a radical journalist who is writing a book about the indignities of the white treatment of blacks, and leaves the country with him when he is persecuted. Throughout it all, she is composed and intelligent beyond her years, noticing at seventeen, for instance, the futility of psychotherapy: “I won’t stay much longer, Ben. They’re so solemn and miserable there in the waitingroom. Those ladies with perfect hairdos, those horribly skinny girls, those sulky kids who look as if they’re handcuffed between mothers and fathers. And there’s nothing wrong with them!”

Next she takes up with a European ambassador, as au pair and mistress. Her career is presented as one might present the career of a distantly historical saint:

This is not a period well-documented in anyone’s memory, even, it seems, Hillela’s own…. In the lives of the greatest, there are such lacunae—Christ and Shakespeare disappear from and then reappear in the chronicles that documentation and human memory provide.

The narrator adopts the point of view of a conscientious historian who does not report as certain what cannot certainly be known:

She may have sung and played the guitar in a nightclub; she would soon have picked up the West African beat. She does appear to have left the ambassadorial employ at some point before or not long after she began to be seen with the black South African revolutionary envoy; and she must have had to earn a living somehow.

One is impressed throughout by the wide variety of Hillela’s accomplishments—she also “blow-dried Madame Mézières’ hair so creditably that it looked better than it ever had while Madame Mézières had suffered the heat and din of piped music in Salon Roma under the hands of an Italian from Somalia.” Above all, she is interested in and good at sexual relationships, which facility is praised with almost Laurentian reverence. As a perfect companion to revolutionaries, Hillela knows her place, “prone,” as the old SDS leaders used to say. It’s not Hillela herself, of course, who will rule, but her man.

Next she becomes the wife of the black revolutionary, Whaila, who is assassinated shortly after. They have a daughter named after Winnie Mandela who will grow up to be a model. Next she goes to Eastern Europe and visits factories, almost remarries in America, returns to Africa as the mistress, then wife, of another black leader, Reuel.

The possibility of satire occurs to the reader. But one is told by South African friends that there are details, keys, allusions to real events and people, known to other South Africans, that are obscure, naturally, to the average American reader, for whom Hillela’s romantic story seems more to be a dream sequence than grounded in quotidian political reality. In all, her story has many of the common features of the lives of mythic heroes—uncertainty of parentage, incest (here modified in that she only sleeps with her cousin), orphan or foundling status. Or Hillela is like Cinderella, the despised daughter, who rises to palaces and presidencies through her alliances with a series of princes—though the sexy, charming, energetic, handsome black princes of this narrative, it must be admitted, with their glossy bodies and their wit, do not seem much like the real African dignitaries we meet on the MacNeil/Lehrer show. Or Hillela is the inspiring Woman of those political narratives of the Thirties, the perfect political adjunct and sexual handmaiden. It seems unlikely that Gordimer did not have these antecedents in mind.

As in Gordimer’s other work, we often feel a certain malice toward white people, especially those of her own camp—English speakers, bourgeois liberals, radicals, Jewish intellectuals. The Afrikaners are either beyond the pale or, in their benightedness, due a certain sympathy. One always feels her empathy and affection for blacks. As for Hillela, there are often in the works of good writers one or two characters to whom the author seems more tender than the reader can be, and this partiality may bring out in the reader a certain irritation, like that one feels for the favorite but unattractive child of a friend, who never notices its faults. One thinks, say, of certain Salinger characters, or of the potent Irish giant O’Shaugnessy in Norman Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself—most writers have an idealized self somewhere. Hillela, in fact, seems a lot like Gordimer’s own description of herself when young: “a bolter,…I seem able to discipline myself, but from a very early age have been unable to be disciplined by other people.” In describing other characters, Gordimer usually writes with a kind of objectivity amounting almost to distaste; we like Bam and Maureen, in July’s People, better than she may. We may like Hillela less than she does. Or are we meant to?

Advertisement

The language can be powerful, or parodic, as here, in an insignificant episode where a schoolboy is embarrassed to get an erection:

His distress caused his flesh to rise. The other boys, and some of the girls, almost forgot the danger of shrieking with laughter. They pelted uprooted lily pads on the poor blind thing Hillela saw standing firm under baggy school underpants.

That “poor blind thing” is reminiscent of nothing so much as Lawrence at his most miscalculated. But elsewhere, Gordimer gives us an Africa clearer than any other writer has done:

The black labourers who did not see her in their inward gaze of weariness, their self-image of religion and race, suddenly unrolled mats towards the East and bowed their heads to the ground. Their seamed heels were raised, naked, as they kneeled, their feet tense. The draped fishnets enlaced the sunset like the leads of stained-glass windows.

But Hillela herself, because always reported on from a distance, with almost none of her thoughts or feelings revealed, is remote and therefore not sympathetic or “real.” This is obviously for a writer of Gordimer’s technical skill a matter of deliberate strategy. It seems possible that the author is trying, as Krauss points out, to have it both ways by imitating, while castigating, romantic delusion, but one is reminded of those school-day admonitions against the fallacy of imitative form.

The tone of the political interpolations is angrily authentic:

The laws made of skin and hair fill the statute books in Pretoria; their gaudy savagery paints the bodies of Afrikaner diplomats under three-piece American suits and Italian silk ties. The stinking fetish made of contrasting bits of skin and hair, the scalping of millions of lives, dangles on the cross in place of Christ. Skin and hair. It has mattered more than anything else in the world.

This is not, however, an unfamiliar exhortation, or one we need to be convinced of. Issues too are discussed in a way that reminds one of another American political era: Q. “And what kind of decent regime can come out of people like that, even if they do win. From what you say, half the time they behave like the crowd they’re trying to get rid of.” A. “Just as both sides have always done in every war. That crowd has to be fought with its own tactics—what else is war? You’re a victim, or you fight and make victims.” “She [Hillela] took sides in the general horror, she condoned means for ends.” Black savagery to other blacks is “the horrible end of all whites have done.”

The work ends with an image of black power and potency: “Cannons ejaculate from the Castle.” Blacks have evicted the white regime in South Africa. All is orderly and gracious: A new flag “flares wide in the wind, is smoothed taut by the fist of the wind, the flag of Whaila’s country.”

There is a sense that the liberation army is protecting the police from the crowd; for many years these black policemen took part in the raids upon these people’s homes…. Every now and then they cannot avoid meeting a certain gaze from eyes in the crowd that once burned with tear gas.

This vision is in such obvious contrast to real black policemen being burned to death or dismembered by their angry confreres in South Africa that one can only wonder if the author, borne along by revolutionary hopes, really intends us to believe it, or whether she is mocking the future.

Amid much singing and dancing, a harmonious assemblage of “diplomats, white and black, white churchmen and individuals or representatives of organizations who actively supported the liberation struggle sit among black dignitaries.” Hillela is of course there, on the podium. Various white members of her family have stayed and accepted positions in the new government:

Clive already has been approached by the new Ministry of Agriculture to serve in a consultative capacity on the adaptation of the wine industry to the new social order. He sees no reason to leave. There is no black man with his specialised knowledge in this field, not anywhere.

This final fantasy of a political eventuality so desirable and unlikely must doubtless be reassuring to the South African reader. For others, it calls into question the generic assumptions of the book, the rules by which we must try to understand it. Is the author mocking, predicting, or merely wishing?

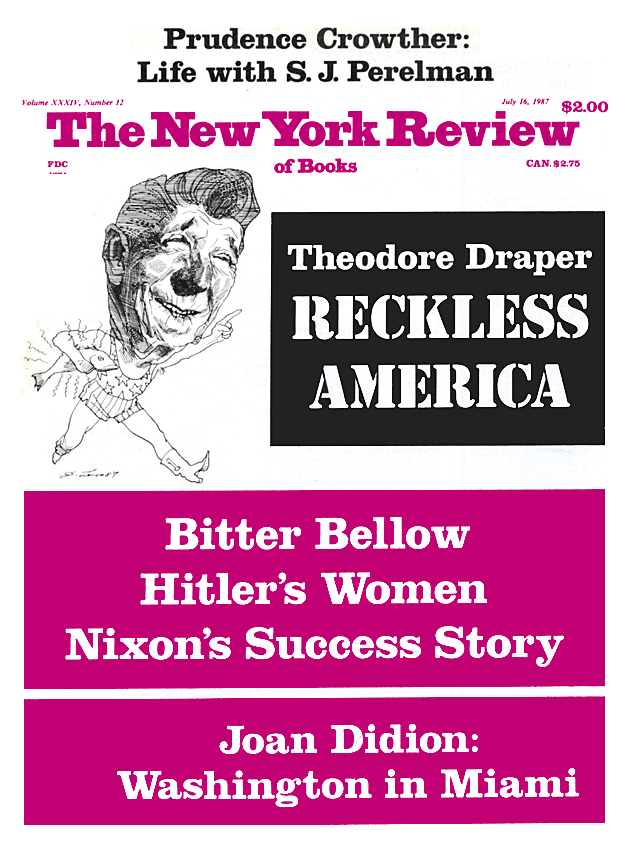

This Issue

July 16, 1987