To the Editors:

In the past few weeks the policies and actions of the Israeli government in the occupied territories have moved to a new level of repression and terror against the Palestinian population. When Palestinian protest demonstrations against 20 years of occupation began in December, the Israeli army responded with lethal force but, after at least 38 Palestinians were killed by Israeli gunfire (The New York Times, January 23, 1988, p. 1), the government officially adopted a new policy: ordering the army and the police to beat Palestinians. “The first priority is to use force, might, beatings,” Defense Minister Rabin has said, and Prime Minister Shamir announced that this policy was “decided upon and instituted by the Government as a whole” (The New York Times, January 23, 1988, p. 6). The newspaper Haaretz, reporting on the army’s actions in fulfilling this new policy, said that “army soldiers, among them officers, beat residents who were pulled from their homes by force without any reason that could be seen by the eye” (op. cit.). Israeli television showed an army captain who said, “You chase anybody you have to and beat him up, and altogether it works pretty well” (op. cit.).

Does any of this sound familiar? It should. These are the terror tactics used by police state governments and free lance fascists the world over, from South Africa to El Salvador. Designed to be at once systematic (they attack Palestinians as a group) and random (anyone can be attacked at any time), they are intended to terrorize and intimidate and silence.

This interpretation doesn’t require surmise, it is the explicit goal of the government’s policy. The Jerusalem Post quotes a military official as saying the policy is aimed at “striking fear of the army” into the Palestinians (op. cit.), and Haaretz reports a military official’s account that the policy was chosen “so that people would be scared of the army” (op. cit.).

One of the lessons of the Holocaust, we are often told, is that we must never let it be repeated: Never Again. But that lesson surely doesn’t only apply to attacks against Jews—or does it? When we hear of the silence of those who did not protest the Nazis’ attacks on the Jews, when we talk about the “good Germans” who didn’t participate but who also didn’t protest—are we only concerned with the fate of Jews? If this is the case, then the lesson of the Holocaust has not been learned.

The sickening policies of the Israeli government must be labeled and attacked for what they are: terrorist oppression against an entire population. The Palestinians are the victims of a historical tragedy. They are guilty of exposing the falsity of the Zionist slogan: “A land without people for a people without land.” Elegant, but also untrue.

The Palestinians were also in that land, and their claim was and is as valid as that of the Jews. Among the greatest of Zionist leaders were some like Martin Buber and Judah Magnes who understood that the moral purpose of Zionism could only be realized through a binational solution. But their views did not prevail, and the seeds of the present horrors were sown long ago.

By now, after 40 years of statehood and 20 years of occupation, there are ample wrongs and grievances on both sides, and an accumulation of enmity that will take generations to subside. And there is no end in sight. The emboldened tactics of the Israeli government—its familiar disregard for the condemnation of world opinion and internal dissent (a trait it shares with other repressive regimes)—only deepen a sense of despair and futility. But one thing is clear: there must be no collusion of silence this time. That silence must never happen again.

Larry Gross

Professor of Communications

The Annenberg School of Communications

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Frank Furstenberg

Professor of Sociology

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Also signed by the following members of the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania:

Roger Abrahams, Folklore and Folklife; Paul Allison, Sociology; Christine Bachen, Communications; Dan Ben-Amos, Folklore and Folklife; Fred Block, Sociology; Michelle Fine, Education; Peter Freyd, Mathematics; Oscar Gandy, Communications; George Gerbner, Communications; Ilona Gerbner, Theatre Arts; Kenneth Goldstein, Folklore and Folklife; Edward Herman, Finance; Pedro Hernandez-Ramos, Communications; Klaus Krippendorff, Communications; William Labov, Linguistics; Walter Licht, History; Carolyn Marvin, Communications; Ervin Miller, Finance; Alexander Nehamas, Philosophy; Gerald Porter, Mathematics; Samuel Preston, Sociology; Charles Rosenberg, History and Sociology of Science; Gillian Sankoff, Linguistics, Herbert Smith, Sociology; Amos Vogel, Communications

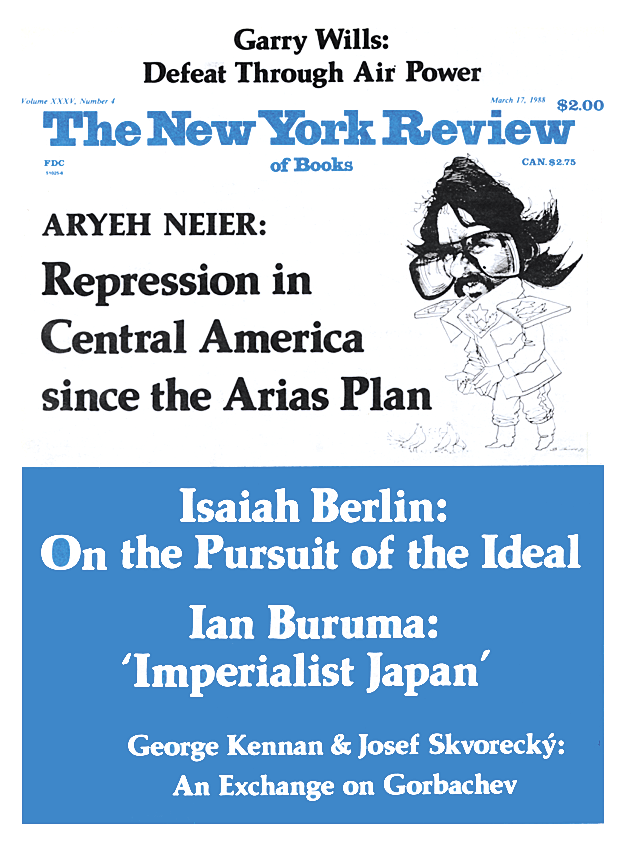

This Issue

March 17, 1988