In response to:

'The Mystery of Max Eitingon': An Exchange from the June 16, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

I have been reading with a great interest the polemics about Eitingon [Letters, NYR, June 16]: presenting a French police file unavailable in our country, I had myself written five lines about him.

Horresco referens. The terrible Theodore Draper writes that the reference to me (Note, not to my paper, to me!) is a good example of how not to do research, that I wrote a “nonsense,” finding my information in “one of the most unreliable passages in the French police file.” He asserts that, for me, Eitingon is a “high-functionary” and, nine lines further, that I “made him into a fur merchant.”

I have reread scrupulously my paper: “La main d’oeuvre blanche de Staline,” in Cahiers Léon Trotsky, no. 24, 1985, p. 69. It is clear enough. I did not write that. And Theodore Draper is unable to tell us why the police report used in the Plevitskaia trial—does he know it?—is “one of the most unreliable….”

Two questions: does Theodore Draper read French? If not, it could be an explanation. Why such a passion about the Eitingon case? Is it not possible for Draper to discuss opinions without distorting or even slandering? Why?

I am sorry. I was really an admirer of his historical work.

Pierre Broué

Professor of History

University of Social Sciences of Grenoble

Grenoble, France

Theodore Draper replies:

Now there is the mystery of Pierre Broué. How can he have misread his own article?

On page 79 (not 69) of his article, “La main d’oeuvre ‘blanche’ de Staline,” he wrote:

Apparaît aussi un nom sinistre, celui d’Eitingon, médecin ou “haut-fonction-naire,” ami de Marie Bonaparte, qui écoule sur le marché des fourrures “saisies en Sibérie”: ce frère de l’amant de Caridad Mercader est le protecteur de la Plevitskaia.

In my letter in The New York Review of June 16, 1988, I rendered this sentence as follows:

Broué refers to “a sinister name, that of Eitingon, doctor or ‘high-functionary,’ friend of Marie Bonaparte, who traded in the market of furs ‘confiscated in Siberia’ ” and, as the brother of “Naum” Eitingon, was “the protecteur of Plevitskaya.”

The question is not whether I can read French; it is whether Broué can read English.

I also wish to take this opportunity to correct the following statement in my reply to Stephen Schwartz’s letter in The New York Review of June 16, 1988: “This article had previously been submitted to a well-known magazine, which sent it to a knowledgeable reader who happened to have known Dr. Max Eitingon and advised the editor to reject it.” Mr. Schwartz has informed the editors of The New York Review that he had sent his article to Martin Peretz, editor of The New Republic, “personally,” after having submitted it to The New York Times Book Review. When Mr. Peretz sent the article to Walter Laqueur, the latter naturally thought that it had been submitted to The New Republic. Mr. Laqueur has now informed me that he had commented that the evidence in the article was unconvincing but had expressed no opinion as to whether the article should be published or not. Mr. Laqueur also recalls that he had met Dr. Max Eitingon a few times and knew the Eitingon circle in Jerusalem in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It is significant that this is the only statement in my reply to which Mr. Schwartz has made any objection; it has nothing to do with the issues bearing on the case of Max Eitingon.

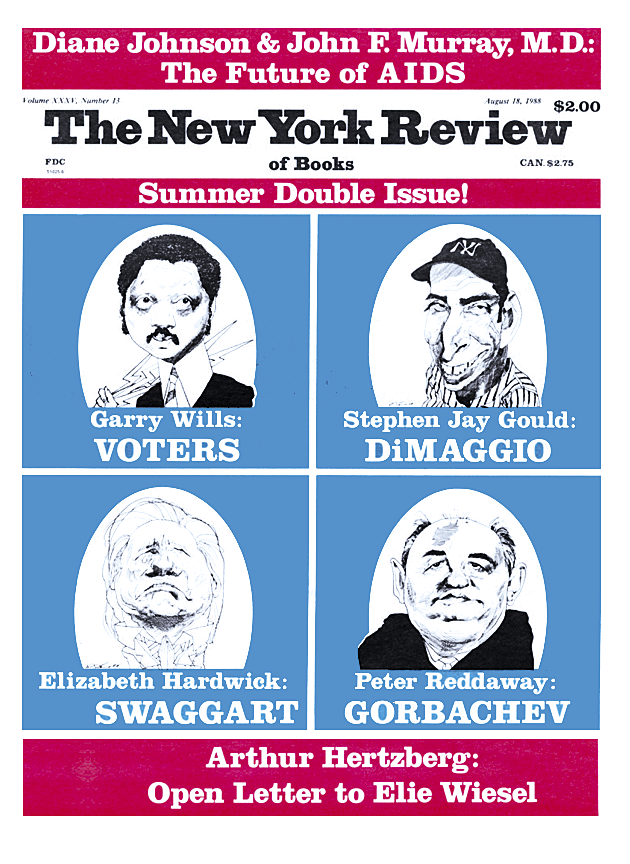

This Issue

August 18, 1988