In response to:

The Morning After from the September 29, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

I would like to comment on some important aspects of Anton Shammas’s article, “The Morning After,” that appeared in the September 29 issue of The New York Review of Books. Shammas supports the existence of two states between the Mediterranean and the Jordan river: Palestine and Israel, and so do I. However, strangely enough, he doesn’t rely on, and even rejects, the only real reason for the two-states solution. Obviously, that reason is the existence of two separate nations in Eretz Israel–Palestine, each with its own language, history, cultural affiliations, etc., each constituting a majority in a certain part of the country, and having the basic right for self-determination within a separate political framework. So when Shammas is reluctant to accept the predominantly Jewish character of Israel within the June 4, 1967, borders, he is not only criticizing an ideological and political superstructure, but he is also ignoring the demographic, cultural, and social realities which he should have taken into account. Moreover, his reluctance to rely on two nations’ existence as the real basis for the two-states solution makes him overlook some important and deep-rooted socio-psychological factors.

In fact, both the Jewish-Israelis and the Palestinians in Israel just don’t feel that they belong to one nation. The Jewish-Israelis’ view is that they constitute the Jewish-Israeli nation, and the Israeli liberals’ and left-wingers’ support for the Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza is based, first and foremost, on the self-determination argument. In addition, the vast majority of Israel’s Palestinian citizens regard themselves as belonging to the Arab-Palestinian nation. Of course, Palestinians in Israel would prefer to be, and should be, citizens with equal rights and duties, and it may well be that they don’t particularly like to be referred to as a “minority.” But it seems to me that they would like even less Shammas’s rather prescriptive notion of one Israeli, non-Jewish and non-Arab, nation, based purely on citizenship. Accordingly, it is not surprising that, concerning this issue, Shammas is engaged in controversy not only with people like me (i.e., with most of leftwing Hebrew writers), but also with Palestinian leaders in Israel (e.g. a non-communist Knesset member A. Darausha, and communist ideologists), because of their usage of terms like “Palestinian minority in Israel,” “that part of the Palestinian nation which lives in Israel,” or “Palestinians with Israeli citizenship,” terms which are not acceptable according to his theory of nationhood.

In any event, if the ethnic, or national, basis of the two-states solution is negated, why does Shammas reject the one-state solution, as applied by extremists on both sides to the entire territory of Eretz Israel–Palestine? But, if he accepts the two-states solution, it should obviously follow that both the Israelis and the Palestinians should, in their respective states, have the right and the opportunity to establish and foster cultural links pertinent to their histories and close to their hearts. For example, it is obvious that the future Palestinian state will foster special cultural and political relations with various Arab states and communities. Would such an Arabic, ethnic-cum-cultural stance of the Palestinian state be also considered as unduly reactionary or anti-democratic by Shammas? Does he not realize that most Israelis want to maintain some cultural links with Jewish communities all over the world, much more than with the Norwegians, for example, or with the Turks? What is particularly wrong or reactionary about that?

It is true that such affiliations with the Jewish Diaspora make Israel, or the Jewish Israelis, “ethnically oriented”; but the same, and even more, may be said of the Palestinians, who are, of course, “ethnically oriented” in the direction of the cosmos of Arab language and culture. Even the problem of the special historical affinities between Jewish culture and Jewish religion resembles very much the similar and very special historical links between the Arab culture and Islam. (This historical affinity is pertinent even to Christian Arabs.) Now, both Shammas and I are in favor of separating state and religion, but this doesn’t imply that we can, or should, ignore the predominantly Arabic context of the Palestinian history and culture and the predominantly Jewish context of the Israeli history and culture.

Gabriel Moked

Tel Aviv, Israel

Anton Shammas replies:

On October 18, the Israeli Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Kach, Meir Kahane’s party (which advocates the expulsion of Arabs from Eretz Israel), to participate in the November 1 elections. The legal grounds for the disqualification were also used, paradoxically enough, as the legal grounds for the appeal.

The Israeli law states that

a party shall not participate in elections to the Knesset if its objects or activities entail any of the following:

- negation of the existence of the State of Israel as the State of the Jewish people;

- negation of the democratic character of the state;

incitement to racism.

Kahane’s lawyer contended, rather brilliantly, that clause number 2 is the negation of clause number 1; and that his client is struggling for the existence of the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people, which means, consequently, that it cannot be a democratic state. The Supreme Court ruled that (page 14 of its decision) “the existence of the state of Israel as the state of the Jewish people does not negate its democratic nature, as the Frenchness of France does not negate its democratic nature. The essential principle of clause 1 does not negate that of clause 2, and both clauses could co-exist in a complete harmony.”

This law, incidentally, was supported by Kahane in the Knesset, when it was passed three years ago. Gabriel Moked, a brilliant reader of literary texts, knows perfectly well, as I know, that the five honorable judges of the Supreme Court were trying to square the ethnocentrifugal circle of the Jewish state. It takes a great deal of numbed logic to rule that the Jewishness of Israel equals the Frenchness of France. (As a non-Jew in Israel, am I to take it that my counterpart in France is a non-Frenchman?) Even the words themselves can feel the discrepancy between the two parts of this odd analogy.

The gist of Moked’s argument is that he is for a Jewish-Israeli and a Palestinian nation, and that both nations are entitled, respectively, to a nation-state. In his two-state solution, he does not seem to offer a real answer to those 700,000 Palestinians who are, like myself, Israeli citizens. “Of course,” he says, “Palestinians in Israel would prefer to be, and should be, citizens with equal rights and duties.” Frankly my dear, as Palestinians say, I don’t understand how this could be achieved under the current setup unless we convert to Judaism (not Israelism), or unless—which I’m reluctant to say—Moked’s views are the left-wing mirror image of Kahane’s world picture.

I hope the results of the last elections in Israel have opened the eyes of Moked to the two musics he will have to face in the foreseeable future: either an ultraorthodox, strictly Jewish state, alienated from world Jewry; or, instead, a democratic Israel, on this side of the Green Line, that belongs to its citizens. He has to make up his mind between living alone with the leader of the National Religious party as his minister of education, or with me, as an Israeli partner. There is no third choice I’m afraid.

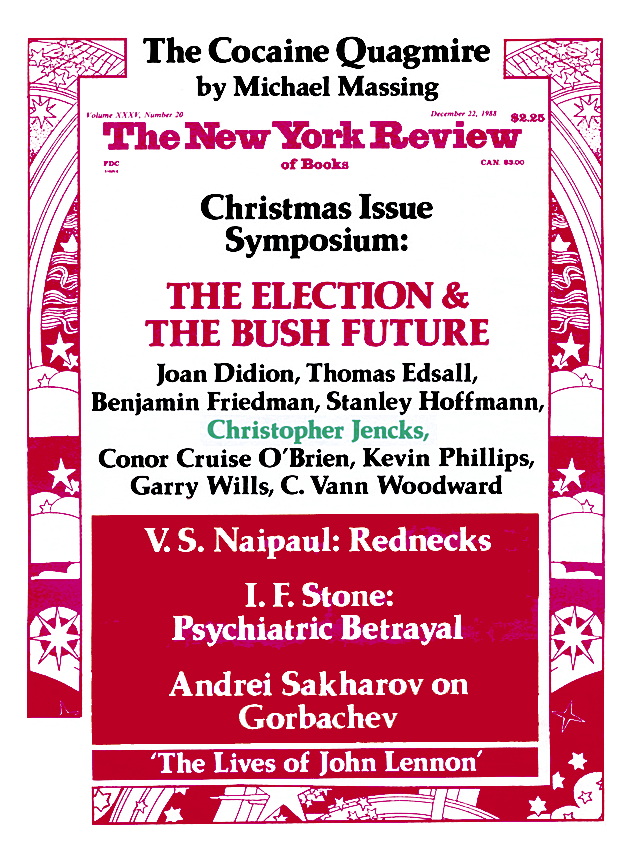

This Issue

December 22, 1988