1.

It is said that American prosperity is fading in a bleach of educational incompetence, and that a large proportion of our incoming work force can neither adjust to new technologies nor perform high-level communicative tasks. “In math and science,” the education researcher John Chubb recently observed, “U.S. students rank dead last in any comparison with students from the nations that are our leading competitors.”1 Last October, an editorial in The Washington Post commented on

the education-linked difficulty facing the large number of workers in this country who, not that long ago, could qualify for a wide range of entry-level, decently paying jobs without sophisticated technical skills or in many cases a high school diploma. As we constantly hear, these jobs are mostly gone, replaced by more technically demanding and autonomous jobs that need employees with higher-order skills. Many employers, especially urban employers in cities with troubled school systems, say they cannot fill these jobs with the available high school graduates.2

Current public concern over filling jobs and competing with other nations offers a historic opportunity to improve all dimensions of American education. Today, more than in any earlier time in our history, purely utilitarian aims happen to coincide with the highest humanistic and civic purposes of schooling, such as promoting a more just and harmonious society, creating an informed citizenry, and teaching our children to understand and appreciate the worlds of nature, culture, and history. These aims coincide today with those of economic utility because the information age has made purely vocational training obsolete. Vocations change their character so rapidly that the most appropriate preparation for today’s workplace is an ability to adapt to new kinds of jobs that may not have existed when one was in school. The best possible vocational training is to cultivate general abilities to communicate and learn—abilities that can only be gained through a broad humanistic and scientific education.

At a conference of college deans this fall, I heard a chorus of anecdotes about the declining knowledge and abilities of entering freshmen. To these administrators, the debate over Stanford University’s required courses seemed interesting but less than momentous compared with the problem of preparing students to participate intelligently in any university-level curriculum. American colleges and universities at their best are still among the finest in the world. But in many of them the educational level of incoming students is so low that the first and second years of college must be largely devoted to remedial work. In the American school system, it is mainly those who start well who finish well. Elementary-school teachers have told me sadly that among their third and fourth graders they are able to identify future dropouts with great accuracy, because they know that the school system will not overcome the initial academic lag of poor minority children. Business leaders and the general public are coming to recognize that the gravest, most recalcitrant problems of American education can be traced back to secondary and, above all, elementary schooling.

The latest news of American school performance comes from the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). Of the educational reports that have numbed our minds recently, none is more informative than the IEA’s 1988 report on science achievement in seventeen countries.3 The schools of all nations teach the same basic knowledge about chemistry, physics, and biology. Hence, achievement in science is an excellent point of comparison for national systems of education. In the IEA comparisons, the rank order of the US was low for all three age groups tested: ages ten, fourteen, and sixteen to seventeen. But, as the report points out, the most significant results concern fourteen-year-olds. Age fourteen is pivotal, since children haven’t yet started intensive training in specialized high schools, but they have, in effect, graduated from elementary school. Their test results are undistorted by variations in the sequence of instruction in different elementary systems. Moreover, international comparisons at that point in schooling are inherently fair, since at age fourteen, 90 percent of all children in the developed nations are still in school. We Americans cannot claim that our results are inferior because our schools virtuously cast a broader demographic net than do other nations.

The performance of American fourteen-year-olds was singled out for special mention in the IEA executive summary, from which I quote:

The U.S.A. was third to last out of seventeen countries, with Hong Kong and the Philippines being in the sixteenth and seventeenth places. Thailand had a score equal to that of the U.S.A…. The IEA conducted its last survey of science achievement in 1970…. The United States has dropped from seventh out of seventeen countries to third from bottom.4

Why has there been so little discussion of such immensely significant news? Five years after the much publicized National Commission report A Nation at Risk, such reports perhaps no longer startle us or add to the picture we already have. Perhaps education reporters may assume that so much energy and thought are already going into school reform that it serves no useful purpose to add to the literature of alarm. But my experiences with apologists for American education as well as with its critics and reformers during the months since the publication of my book Cultural Literacy have led me to think otherwise. Most reform efforts, including many that are highly promising, concentrate on the organization and administration of schooling. Recently, for example, there has been much emphasis on establishing cooperative relations with parents of poor children from minority groups, on merit pay for good teaching, and on the development of magnet schools. The IEA science report, with its emphasis on knowledge, has a special value because it encourages us to consider the specific curriculum of the elementary school.

Advertisement

Of course science is just one field of instruction in elementary school, and its significance can be exaggerated. More important than specific information, according to the most influential American education experts, is the possession of general academic skills. I shall not retrace the steps by which I argued in Cultural Literacy that a misguided emphasis on skills has been the single most disastrous mistake of American schooling during the past forty years. An emphasis on skills coupled with a derogation of “mere facts” is a cast of mind that distinguishes the thought-world of education professors from that of common sense. Ordinary people, as Aristotle observed, think facts are important, and take pleasure in knowing them. They assume that facts are essential to knowledge and education. This is not the case with most of the interlocking institutions that make up the educational establishment, including the people responsible for running most teachers’ colleges and school districts, as well as professional curriculum organizations such as the ASCD (Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) and the publishers and buyers of text-books. Most of the experts who are in a position to affect the school curriculum think mere facts are deadening, unless they are instantly made meaningful by being “integrated” into the child’s world.

This ambivalent attitude to specific information, so different from the attitude of most ordinary people, has a double importance to the educational establishment. American schools of education are conceived on the principle that pedagogy itself is a skill that can be applied to all subject matter. Many of the courses taken by prospective teachers emphasize techniques of teaching and ways of improving students’ “inferencing skills” and other general abilities as they are defined by theories of educational psychology. Thus the principle that abstractly defined skills are more important than specific information cannot be relinquished without compromising the fundamental assumptions of education schools. If educationists did not assert that skill in pedagogy is more important than mere information (which can always be looked up) they would not be able to resist the common-sense view that the best teachers, in both the early grades and the later ones, would tend to be those who are well prepared in the subject that they teach. The derogation of mere facts, besides serving the institutional interests of education schools, is also politically useful to educational administrators in a contentious and diverse country where parents can often be depended upon to raise objections whenever the specifics of the school curriculum are openly discussed. An approach emphasizing “reading skills,” for example, conveniently avoids argument about what is read.

The 1970 IEA report on science ranked the US seventh and the present IEA report ranks the US third from bottom. Our 1970 average scores on the verbal Scholastic Aptitude Test, soon after their high point around 1965, were also significantly higher than they are now. The historical parallel is significant, although the year 1970 was of no particular significance in educational history. Nineteen seventy happened to be the year that the previous IEA evaluation of science achievement was made and also a year when SAT scores had not yet reached bottom in their inexorable movement downward between 1965 and 1980. The causes of that decline had less to do with the turmoil of the 1960s than with the miseducation that had established itself on a vast scale in the preceding decades, when the high school graduates of the 1960s and 1970s were entering elementary school. During the 1940s and 1950s a new generation of educators, well indoctrinated in an antitraditional pedagogy emphasizing skills, finally gained control of the nation’s schools and textbooks. Thus the 1940s and 1950s, not the 1960s, were the watershed decades in the recent history of American education.5

The verbal SAT has been much criticized for various kinds of bias, but studies correlating its results with school records have shown that it is a reliable indicator of the general level of education of the students who take it; so we would in any case expect the verbal SAT to show a close historical correlation with results on IEA achievement tests. By the same token, the latest IEA report on science knowledge has implications that are much broader than its immediate findings regarding science. In order to interpret those implications I shall try to explain why these two very different tests—the verbal SAT and the IEA test of science—show the same pattern of American decline between 1970 and the present. To understand that pattern is to begin to grasp one of the things that have gone wrong.

Advertisement

The Scholastic Aptitude Test is misnamed. As its critics have observed, it only measures aptitudes if we understand the term aptitude to mean acquired aptitude. It is really a vocabulary test, and the bookish vocabulary that it tests is inherently related to standard academic disciplines; it does not normally ask questions involving the vocabulary of popular culture. The test is divided into four question types: antonyms, analogies, sentence completion, and reading comprehension. All of these types of questions are ultimately grounded in vocabulary. The one exception might seem to be analogy questions, which are assumed to test thinking skill, but I doubt that they do so to any significant degree. For instance, most seventeen-year-olds will correctly answer the following question:

NAIL:HAND :: (A) talon:eagle (B) tooth:bite (C) toe:foot (D) claw: paw (E) hoof:horse

By contrast, fewer students can be expected correctly to answer this analogy question:

VINDICTIVE:REVENGE :: (A) belligerent:territory (B) repentant:guilt (C) ravenous:satiation (D) hostile: brutality (E) forgiving:clemency 6

Yet the thinking skills required to answer both questions are the same. A student who can correctly answer the first ipso facto has the skill to answer the second—but only if he or she knows what the words mean. In short, the verbal SAT is essentially a vocabulary test in all of its components.

But calling the verbal SAT a vocabulary test is almost as misleading as calling it an aptitude test. Vocabulary is more than words; it is also knowledge. To know what a word means is to know the reality it refers to, and if you don’t know the reality you don’t know the word well enough to answer a question about it on the verbal SAT. Vindictiveness and revenge are realities as much as nails and hands. And since the verbal SAT is an extensive and diverse vocabulary test, it is implicitly at the same time a test of general knowledge. If you know a broad diversity of words you also most likely know a broad diversity of things. The verbal SAT therefore correlates well with a broad range of tests that probe academic achievement. Knowledge builds upon knowledge. The best way to gain new knowledge is already to possess an informed mind that can assimilate various sorts of new information.

2.

Because learning depends on prior knowledge, even at the earliest stages of schooling, young children ought ideally to arrive at first grade with a reasonably broad fund of information. But many children are not so fortunate as to come from families that provide them with a fairly extensive knowledge of words and ideas before they enter school. An excellent but enormously expensive way of making up deficiencies in elementary knowledge on the part of young children is to tutor them—the tutorial method being the fastest means for imparting new knowledge. A tutor becomes aware of the unique temperament of the child and will be able to arouse curiosity and make a child feel rewarded for learning. Also, since children learn new information by attaching it to already known information, a tutor’s awareness of the child’s own distinctive structure of conceptions will enable the tutor to impart further knowledge with great effectiveness.

For example, a tutor who wished to teach a pupil about atomic structure might use an analogy with the solar system—if the pupil already knew about the solar system. Analogies could then be drawn between planets revolving around the sun and electrons revolving around the nucleus, between the attractive force of gravity and the attractive force of opposed electrical charges, and so on. In short, a teacher’s awareness of what a pupil already knows and consequent ability to form analogies based on that awareness is a characteristic advantage of tutorial instruction. The principle can be generalized. Since knowledge builds on knowledge, the technique of using analogies (including metaphors) is an indispensable device of all kinds of teaching, not just of tutorials.

Consider now the primal scene of education in the modern elementary school. Let us assume that a teacher wishes to inform a class of some twenty pupils about the structure of atoms, and that she plans to base the day’s instruction on an analogy with the solar system. She knows that the instruction will be effective only to the extent that all the students in the class already know about the solar system. A good teacher would probably try to find out. “Now, class, how many of you know about the solar system?” Fifteen hands go up. Five stay down. What is a teacher to do in this typical circumstance in the contemporary American school?

If he or she pauses to explain the solar system, a class period is lost, and fifteen of the twenty students are bored and deprived of knowledge for that day. If the teacher plunges ahead with atomic structure, the hapless five—they are most likely to be poor or minority students—are bored, humiliated, and deprived, because they cannot comprehend the teacher’s explanation. At the end of class they will not understand either the solar system or atomic structure. Under these circumstances, either one group or the other will be deprived of the knowledge the teacher had hoped to impart to all the pupils in the class.

The problem is more subtle and pervasive than the example suggests because a teacher’s analogies are usually less elaborate and extended than the one between atomic structure and the solar system. Analogy forms part of the very texture of a teacher’s discourse. Teachers refer constantly to concepts like Cinderella or the American Revolution in order to connect new pieces of information with things that are already familiar. But if the analogies are consistently unfamiliar to ill-prepared children, they will fall ever further behind, or else the teacher will be compelled to make instruction very slow, repetitive, and inefficient, to the boredom of better prepared students.

No doubt the problem of imperfectly shared background knowledge is in some degree inherent in any classroom. But in American classrooms today, the problem has become pervasive and acute. I am told by those who teach mathematics and foreign languages, subjects which build upon careful sequences of knowledge, that new material cannot be introduced into the elementary-school classroom until the middle of November. And throughout the year, the chief shared experience that an American teacher can rely on in making analogies is often a topic or concept that has already been covered in the same class on a previous day. But what was “covered” was not necessarily understood and learned by all pupils, since in almost every class period some children will have been in the unfortunate position of the five students who did not know about the solar system.

The dilemma is almost inevitably resolved at the expense of poor and minority students. The pervasiveness of the academic caste system that is thus created was confirmed to me recently when a researcher who had visited elementary classrooms throughout the nation on behalf of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching telephoned me saying that he needed to talk to somebody. He wanted to tell me about the observations he had made in dozens of schools. In a typical fifth-grade classroom, he said, all pupils are able to sound out the words from their books, and explain what the individual words mean. They apparently can “read,” but when they are asked questions about a passage they have read, usually only middle-class pupils show an understanding of it. Many poor and minority pupils make little sense of the passage as a whole, and during class discussion of it they exhibit signs of boredom, discomfort, and hostility.

Educational specialists are of course aware of this situation, which they attribute to social forces beyond anyone’s control. Like practically all people of good will, they favor Head Start, the training of parents, alliances between home and school, intensive remedial work, and other programs designed to improve the learning of minority pupils. These initiatives are in themselves of tremendous value. But unfortunately, given the cast of mind of educational specialists, the standard analysis of the bored and humiliated pupils described by the Carnegie researcher is that such children lack “inferencing skills,” “organizing strategies,” and other “higher-order thinking skills.” These deficiencies should therefore be corrected through remedial training designed to develop the missing skills.

One wonders if the educational experts who make such analyses are aware that outside the school, these same minority children are street-smart and can deal quickly and effectively with a world of great complexity. Outside school, their language, as the sociolinguist William Labov has shown in detail, exhibits wit, narrative ability, syntactical sophistication, and complex inferencing skills that would tax the powers of any pedagogical expert who happened not to be familiar with the background knowledge and conventions the children take for granted.7 A more likely explanation of the lack of “higher-order thinking skills” on the part of these children is therefore that they have been deprived of the background knowledge and conventions that they need in order to understand what is being said by teachers and books. Obviously children cannot learn from classroom discourse they do not understand; but the connection between the language of the classroom and learning goes deeper than that self-evident observation. In the solar-system analogy, it would not have been sufficient to explain what the word “solar” means, or to substitute more familiar terms like “sun system.” The children needed to have a concrete mental image of the solar system and how it works in order to learn from the teacher’s analogy.

If we generalize from this example, we derive a principle that few experienced teachers would dispute, although many are not in a position to act upon it. Children who possess broad background knowledge will be able to learn new things more readily than those who lack it. This general principle of learning could be described, in an analogy with economics, as earning new wealth from old intellectual capital.8 A diligent first grader who starts off with a dollar’s worth of intellectual capital will be able to put it to work to gain, say, 15 percent a year. But a child who starts out with a dime’s worth will not only gain less new intellectual wealth in absolute terms, but will earn even that pittance at a lower annual rate, say 7 percent. Why at a lower rate? Because, if we again imagine the classroom scene, we will notice that the use made of intellectual capital by deprived students is not only less extensive but also less efficient than the use made by well-informed students. Teachers I have talked to say that these deprived students, future dropouts, actively resist the enterprise that causes their boredom and humiliation; they develop an anti-school ethos; they are motivated not to use even that which they have.

3.

Thus, inexorably, in the modern American classroom, the intellectual gap between the haves and have nots increases over time. The difficulty of overcoming this widening knowledge gap makes adult illiteracy an intractable problem. But adult illiteracy, as troubling and significant as it is, is not the chief symptom of American educational failure. About 80 percent of our population is neither illiterate nor poor. Yet today, even literate, middle-class students who have recently graduated from American high schools and colleges exhibit a significant knowledge gap when compared to students from other nations. On the international scene, American students are to their Swedish counterparts as, on the national scene, deprived students are to those of the middle class.

I believe that a chief cause of our poor showing in international educational comparisons is our failure to take a systematic approach to shared knowledge in elementary schools. American students participate in schooling under a tremendous disadvantage. Classroom transactions in which relevant knowledge is not widely shared are extremely ineffectual transactions. The impossibility of relying on common knowledge among the diverse pupils in American classrooms causes the children in our elementary schools to learn less for each day or hour in school than children in other countries. This low educational productivity may have mattered less when there was a smaller correlation between educational and economic productivity, but now it matters a lot.

The inherent ineffectualness of American elementary schooling not only handicaps our brightest pupils, it also creates, in the name of democratic diversity, one of the most unjust and inegalitarian school systems in the developed world. That is another implication of the IEA report on science achievement, which included findings about equality of education in various countries. One way of measuring equality of opportunity in a nation’s school system is to compute the percentage of schools whose average scores fall below a minimal norm. It is reasonable to assume that the average score of an entire school must measure something other than the innate intellectual capacities of its students. Academic talent is randomly distributed throughout the population so far as innate capacities are concerned; average scores tell us more about schools than about children. Moreover, we now know, from the extensive research published by the Brookings Institution, that the quality of schools, more than any other factor, determines the average level of academic achievement.9

One of the most disturbing features of the IEA report was its finding of severe inequality among American elementary schools. In nations with egalitarian school systems, only between 1 and 5 percent of elementary schools fall below a minimal standard. But in the US, 30 percent of our schools fall below the same standard—not a reassuring statistic for a nation that aspires to equality of opportunity for its children. The statistics supplied by the IEA do not tell us which of our schools perform poorly, but we can guess that among them are schools in our inner cities. Britain and Italy also performed badly by the same criterion of school equality, though their nationwide achievement scores are marginally higher than ours.

It happens that the most egalitarian elementary school systems are also the best. With one exception (the Netherlands), the nations that score highest—Hungary, Japan, the Netherlands, English-speaking Canada, Finland, and Sweden—are also the nations that provide the greatest equality of opportunity to their young children. This finding contradicts the widespread belief that truly democratic education must sacrifice quality. The top-scoring nations do both a better and a more democratic job of early education than we do. By now, the reader will not be surprised to learn that the countries that achieve these results tend to teach a standardized curriculum in early grades. Hungarian, Japanese, and Swedish children have a systematic grounding in shared knowledge. Until third graders learn what third graders are supposed to know, they do not pass on to fourth grade. No pupil is allowed to escape the knowledge net.

Here is a general description of the curriculum for elementary schooling in Sweden:

All children in all schools have the same number of Swedish, mathematics, and English periods, etc., throughout their nine years of compulsory schooling. What is more, they cover the same main teaching items in every subject. The amount which pupils can assimilate varies, of course, depending on their individual aptitudes and interests. But the differentiation made in response to the personal aptitudes and interests of individual pupils is based on a common curriculum ensuring that everybody receives a basic grounding in every main teaching item specified for the compulsory or optional subjects. The curricula help to create a universal frame of reference on which to base co-operation and a sense of community.10

American educational specialists have told me that they believe the IEA comparisons are unfair. We are, they say, a pluralistic society which has consciously decided against teaching our young children a standard curriculum. If our schooling is a little inefficient, so be it; we treasure our diversity. We don’t want our children to know all the same things and think all the same thoughts. We don’t want to be like other nations whose school systems produce automatons cut from the same cultural cookie cutters. Those who utter such clichés have not noticed how diverse, independent-minded, and eccentric Swedes and Hungarians and Canadians actually are, despite their having absorbed common knowledge during their elementary education. It is not obvious that a norm of commonly shared information in elementary school destroys diversity of thought any more than does a norm of commonly shared grammar and spelling.

But the basic importance of shared knowledge can be illustrated even if we ignore the un-American practices of other nations, and simply compare the educational performances of California and New York between 1965 and 1980. Both states exemplify American diversity; neither has the advantage of a homogenous culture. Yet in past decades, according to College Board statistics, students in New York have consistently outperformed students in California on the verbal SAT. Why? The basic conditions in the two states are very similar. Approximately the same number of students (100,000) take the test in each state each year. The test takers in each state are probably similar in their socioeconomic characteristics. Many poor and minority children drop out before the tests are given or do not take them. In both states, it is the better prepared students who tend to take the tests.

In the absence of another theory to explain the superior performance of the New York system, let me suggest the following. In the years between 1965 and 1980, before Bill Honig, the current head of public education in California, began applying his formidable energies to school reform, California’s educational system was typically American in that it emphasized “skills” and neglected specific content. Its curriculum guide to language arts in the first six grades recommended no particular books or readings whatever. Its chief advice, much applauded in the introduction to the guide by the then head of public education, was that teachers should be solicitous of children’s self-esteem. Under such “guidelines” it would have been a miracle if teachers in California found that the students had in common a wide range of knowledge.

New York had a different, rather special, tradition. With the threat of the Regents exams looming at graduation (at least for ambitious students), and with the politically protected Board of Regents setting standards of accomplishments for these exams, schools were provided with definite goals to aim for. The typical contents of the Regents exams were known. Throughout the New York system students and teachers expected that certain kinds of knowledge would be tested, and that schools’ reputations and students’ financial help in college depended on the outcomes of these exams. These expectations encouraged a concentration on specific kinds of knowledge in the New York system. We know that tests like the Regents exams encourage schools to include common elements in their curriculums. Indeed, the Dutch rely on such exams exclusively, instead of imposing specific curricular standards on the schools. Thus, while classroom instruction in New York was far from ideal between 1965 and 1980, teachers could depend somewhat more on shared knowledge than could teachers in California. This explanation has the advantage of coinciding with what we know about schooling in general and these two states in particular. It seems worth accepting until a better theory is proposed.

Some have hoped that television might provide children with a common basis for early learning. But television culture consists of multiple channels that randomly impart ephemeral information to random groups. Indeed, very little so-called “popular culture” is shared by a large proportion of American society, and that little is not diverse enough to provide an adequate basis for later schooling. In a modern nation, there is really just one effective vehicle for transmitting widely shared culture—the elementary school. It is the only channel that everyone must tune in. Although television is an immensely powerful medium that can supplement formal education, the elementary school is an even more powerful social-technological device. No cultural institution comes close in effectiveness to this now-rather-old modern invention. And, for reasons I have explained, the most effective elementary-school system uses a single channel—in the form of a standard curriculum.

No doubt American schools are unlikely to adopt a standard elementary-school curriculum on the Swedish model. The idea of such standardization would encounter vigorous resistance from curriculum experts in 15,000 school districts and fifty state departments of education. Even a suggestion of standardization in elementary textbooks would shake up the lucrative world of educational publishing and bring forth statements explaining why diversity of textbooks should be encouraged. American traditions of localism are so deeply established that the public would probably be sympathetic to arguments against standardization.

On the other hand, the evidence is clear that standardized elementary curriculums are inherently productive and egalitarian, and that they do not suppress diversity or dissent in other democratic nations, such as Sweden. Our extreme curricular localism, by contrast, has produced an unproductive and highly discriminatory system whose gravest victims are the poorest and most nomadic elements of our population. While children who stay in one school district sometimes stand a chance of receiving a coherent sequence of instruction, those who move from one district to another, often in the middle of the school year, have no such chance.

As more people come to understand that a fragmented curriculum in the early grades is one inherent cause of our educational shortcomings, public sentiment may gradually come to favor some degree of standardization in elementary grades. But such a change will take a long time and, meanwhile, teachers and pupils are working under severe handicaps that should be alleviated as soon as possible. Although we cannot hope to institute a Scandinavian-style early curriculum, we might still hope to reach agreement among parents and teachers on some minimal goals of knowledge, grade by grade. Following these minimal guidelines would still leave local curriculum experts free to decide on emphases, introduce local subjects, choose textbooks, develop sequences, and, in short, determine most of the curriculum.

4.

What should the minimal goals be, and who should decide them? The two questions are separate. The second question, who should decide, is easily and quickly answered. In the United States nobody has authority to decide upon the content of education for the nation as a whole, and no person or agency is ever likely to acquire such authority. If one set of goals were to be adopted in our 15,000 autonomous school districts, it would be because parents, administrators, principals, and teachers had concluded that a particular standard was useful for the moment and made sense. Among differing proposals for such goals, one of them might turn out to be more useful than others. Presumably that is how the IBM floppy-disk format became widely adopted. It wasn’t necessarily the best format, but it served society much better than having no standard at all.

The second question, concerning what central core of knowledge should be taught to everyone, is not quite as difficult as it appears. About 50 percent of the basic knowledge taught in elementary education is common to all the developed nations. Math, science, world geography, economics, world history, world literature, and technology are similar in most countries. It would be very surprising if the contrary were true. Neither math, nor science, nor world geography much changes its character when it crosses a national or state border.

The other half of basic elementary-school work—that which is national rather than international in character—is, in my experience, at least 80 percent agreed upon right now. Ninety percent of the teachers and other educators I have talked to agree on about 90 percent of the basic items that should be taught in elementary school. I began to ask such questions about three years ago, before the publication of Cultural Literacy, when I formed a foundation to encourage the development of common goals of knowledge in schools.11 The schools that make up the foundation’s network currently number about eight hundred and are found in all fifty states and two protectorates.

The men and women who participate in the network represent black and Hispanic cultures as well as white, middle-class culture, and have been invited to suggest deletions and additions to the goals for knowledge that we have provisionally recommended, and that we constantly revise on the basis of members’ suggestions. The members of the network have offered numerous recommendations for our twelfth-grade list, but have expressed virtually no dissent regarding the items that now appear on our cumulative sixth-grade list. The reason for this easy consensus may be that sixth grade is not the end of schooling, so that apparent omissions might reasonably be repaired in seventh grade or beyond.

Such a tolerant attitude to early minimal standards makes sense. What young pupils mainly need is a fairly broad range of knowledge that they share with their classmates, not absolute uniformity of information. They need to share enough information to make classroom communication effective. To that end, members of the network have been putting in a grade-by-grade sequence the information and ideas they believe should be taught during the first six grades. So far, we have had no dissent from members concerning our provisional sequence of items. At this early stage, the main frustration felt by members of the network is the lack of classroom materials and lesson plans designed to unify and teach the agreed-upon sequences, a crippling handicap. Nonetheless, our experiences so far offer hope that a consensus can be reached on a core of knowledge for the first six grades of schooling.

The reader may be curious to know what the network’s sixth-grade list looks like. Here are just the first few items from some of the twenty categories conceived by the network. Each item merely stands for an event, episode, idea, or person that needs to be explained in depth and linked with others in sequence that will be clear and interesting.

American History to 1865

1492

1776

1861–1865

abolition

Alamo

all men are created equal

American Revolution

Apache Indians

Appleseed, Johnny

Appomattox Court House

Bill of Rights

Boone, Daniel

Booth, John Wilkes

Boston Tea Party

Brown, John

Battle of Bunker Hill

California Gold Rush

Cherokee Indians

Civil War

The Confederacy

The Constitution

Crockett, Davy

Davis, Jefferson

Declaration of Independence

Douglass, Frederick

Literature

Aesop’s Fables

Aladdin’s Lamp

Alice in Wonderland

Andersen, Hans Christian

Angelou, Maya

Arabian Nights

“Baa Baa Black Sheep”

“Beauty and the Beast”

The Big Bad Wolf

“The Boy Who Cried Wolf”

Brothers Grimm

Camelot

Carroll, Lewis

“Casey at the Bat”

Chicken Little

A Christmas Carol

“Cinderella”

Dickens, Charles

Dickinson, Emily

Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Don Quixote

Dracula

“The Fox and the Grapes”

Life Sciences

amphibians

animals

balance of nature

biology

birds

carnivore

cell

chlorophyll

coldblooded

Darwin, Charles

deciduous

dinosaur

ecology

evergreen

evolution

fish

food chain

habitat

herbivore

heredity

hibernation

The reader who has followed my argument this far will understand why I think it a good idea to make a list of what sixth graders should know, despite the fact that a list looks like a simple-minded gimmick. In the current American situation, in which lack of common knowledge impedes both teaching and learning, it has become an evasion not to make a list. The people who understand this best are teachers. After Cultural Literacy appeared, thousands of teachers wrote me to express their agreement with its thesis and their hope that schools would begin to emphasize shared knowledge. What they had been taught in pedagogy courses was being eroded by the realities of their daily experiences in the classroom. I received many moving letters, and teachers now send requests every day for teaching material incorporating the kinds of knowledge I have listed. Their response has been a genuine grass-roots movement, conducted mainly by word of mouth.

The modest efforts of the cultural literacy network are not by themselves going to change the results of the next IEA report. Imparting shared background knowledge is just one of several major reforms that are needed. James Comer, director of Yale’s School Development Program, has explained in detail how, for poor black and other minority children, the “high degree of mutual distrust between home and school…makes it hard to maintain a link between child and teacher that can support development and learning.” To create such a link, he writes, “requires fostering positive interaction between parents and school staff, a task for which most staff people are not trained.” He argues convincingly that it also requires giving the school a new structure, involving teams of counselors and teachers, who would deal with the psychological and social problems of learning as well as the cognitive problems.12 Significant improvement in academic performance cannot be achieved simply by offering children systematic knowledge when they are emotionally unprepared to believe that they can learn or use academic knowledge at all.

Moreover, compiling lists will not create teachers who are well-versed in history, science, and mathematics, and who are well-paid members of a respected profession. It will not convert poor textbooks into the coherent and well-written ones that have been called for by reformers such as Diane Ravitch, Paul Gagnon, and Harriet Tyson-Bernstein. Core knowledge will not convert pencil pushers into good principals and courageous administrators. That transformation is more likely to be encouraged by allowing parents the right to choose their children’s schools. In the large view, the problems of American education are so vast as to make the creation of a few lists seem a trivial contribution, and indeed no single approach could quickly transform a system that has been wandering in the wilderness for forty years.

Despair is premature. The initiative for change in American education has to some extent been taken out of the monopolistic control of the bureaucratic establishment. Behind the elaborate state guidelines, the scope and sequence descriptions, the forms to be filled out, the competency measures to be met, the textbook adoption procedures to be followed, behind the commands emanating from state and local hierarchies, as set forth in documents of pseudoscientific jargon mixed with an officialese combined with pious slogans, behind the whole chaotic and fragmented scene, one feels the stirrings of change—not perhaps within the vast establishment itself, which is still engaged in defensive maneuvers, but among conscientious teachers, principals, and superintendents who are in the front lines.

Although the attempt to win adherence to a standard core of knowledge is but a small part of this larger effort, it is a necessary element. The effort to develop a standard sequence of core knowledge is, to put it bluntly, absolutely essential to effective educational reform in the United States. Amid the other improvements that may occur through better teacher training, better preschool education, stronger alliances between school and home, better remedial education, better textbooks, greater financial inducements, and more flexible school administration—amid all of these badly needed initiatives, the inherent logic of the primal scene of education itself still remains.

When I am feeling hopeful, I imagine to myself how things might change. A few schools scattered over the country will hold their pupils accountable for acquiring an agreed-upon minimum core of knowledge grade by grade. Because classroom work in such schools will be more effective and interesting for their pupils, children will feel more curious and eager. Their abilities to speak, write, and learn will improve noticeably. Students from such schools will make significantly higher scores on standardized tests of scholastic aptitude and achievement. Neighboring schools will observe the results, and, not wishing to be outshone, will follow the lead. District and state offices will find it convenient not to resist these successful undertakings. Even the education establishment itself may in time begin to say in its hundreds of conferences and dozens of journals, which are now vigorously resisting such changes, “We knew it all the time, That was what we were trying to tell you.”

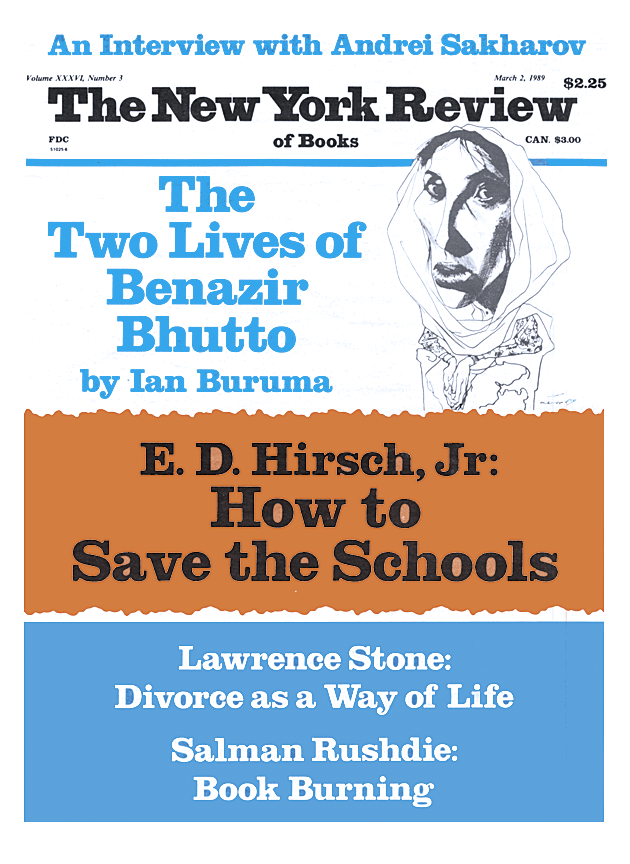

This Issue

March 2, 1989

-

1

Nathan Glazer, John Chubb, Seymour Fliegel, Making Schools Better (Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, 1988), p. 4. ↩

-

2

October 29, 1988. ↩

-

3

International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, Science Achievement in Seventeen Countries: A Preliminary Report (Pergamon, 1988). ↩

-

4

IEA report, p. 2. ↩

-

5

See Diane Ravitch, The Troubled Crusade: American Education, 1945–1980 (Basic Books, 1983), especially pp. 43–80. ↩

-

6

The examples are taken from Karl Weber, Complete Preparation for the SAT (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986). ↩

-

7

See, for instance, William Labov, “The Logic of Nonstandard English,” reprinted in Language and Social Context, P.P. Giglioli, ed. (Penguin, 1972), pp. 179–216. ↩

-

8

The term “intellectual capital” has been used in a different context by Pierre Bourdieu. ↩

-

9

See John Chubb and Terry Moe, What Price Democracy? Politics, Markets and America’s Schools (Brookings Institution, 1988). ↩

-

10

Britta Stenholm, The Swedish School System (Stockholm: The Swedish Institute, 1984), p. 31. ↩

-

11

Activities of the Cultural Literacy Foundation include publishing a news-letter and offering provisional lists of what pupils should know at different grade levels. Its address is 2012-B Morton Drive, Charlottesville, VA 22901. ↩

-

12

See James Comer, “Educating Poor Minority Children,” Scientific American (November 1988), pp. 42–48. ↩