Gita Mehta sets the scene well: India, the Roaring Twenties, the Royal Calcutta Turf Club. Jaya, wife of Prince Pratap of Sirpur, is watching the races, dressed in red and indigo, the Sirpur colors. She is joined by her brother-in-law, Maharajah Victor, a gentle man in love with a Hollywood star:

“The Sirpur colors seem to belong on you, Princess. I often think you are the only one of us who knows who you are.”

“But you are the Maharajah, hukam. You are Sirpur.”

He looked at her and Jaya was shocked at the unhappiness in his eyes. “Only by birth and the tolerance of the British Crown, not because I believe I am a king. I am acting and actors should be allowed to marry actresses.”

That is of course precisely what they were, the rajahs, maharajahs, nawabs, and Nizams of India, actors on a stage set by the British. Effectively emasculated by the Raj, they were useful as vassals to the British Crown, ruling chunks of India, red blotches on the map in a sea of pink, virtually as proxies with British residents watching their every move. Tradition and the mystique of divine kingship lent historical weight to British ideas of “good government.” As long as they acted their parts, the Indian princes could spend their lives at play. And some chose very odd plays indeed.

Mehta uses to wonderful effect a celebrated occasion when the Nawab of Junagadh staged a dog wedding, inviting the crème de la crème of Indian aristocracy for the occasion: “The marriage of the two dogs, Roshanara, veiled and covered in gems, to Bobby, shivering in his wet silk pajamas, was conducted with all the ceremony that would have accompanied the marriage of a royal princess.”

Andrew Robinson, in the latest glossy book for the Indian nostalgia trade, describes the funeral of the Maharajah of Alwar: his impeccably dressed corpse seated stiffly upright in his favorite golden Hispano-Suiza, the rear of which was a copy of the British coronation coach, complete with carriage lamps and gold crowns. Alas, there are no pictures of this occasion. We have to make do instead with Sumio Uchiyama’s colorful photos, mostly of the charming Maharajah of Jodhpur (Eton and Oxford) striking traditional poses.

Another noteworthy player, cited by Robinson, was Sayaji Rao, the Gaekwad of Baroda, who trained his parrots to ride silver bicycles and perform dainty dramatic scenes. His granddaughter, Gayatri Devi, remembered one in particular “in which a parrot was run over by a car, examined by a parrot doctor, and finally carried off on a stretcher by parrot bearers. The grand climax of their performance was always a salute fired on a silver cannon.”1

All this is fun to read of course. The excesses of bored men with unlimited means always are. But Mehta’s novel, greatly to her credit, is more than a catalog of bizarre fancies. The story of Jaya is a story of liberation: the liberation of a woman, whose story begins in the opulent seclusion of a palace harem and ends in a court of law, where she registers her name as a political candidate in a newly independent India. But, again to her credit, it is not simply a story of brave, freedom-loving Indians versus arrogant oppressive Brits. It is much more ambivalent than that, for the agents of change, and ultimately of freedom, are often the very same things that oppress and destroy.

Two symbols recur frequently throughout the book: the machine and the bracelet. Glass bangles or glittering gauntlets are forever clinking on Jaya’s wrists like manacles, symbols of her young servitude to tradition. Dressed by servants for her marriage to a man she has never even met, she felt “suffocated as the women scratched her body with jeweled gauntlets and heavy anklets.” But when the young Englishman she had loved dances with her at a ball, her bangles break in his white glove. And when her maidservants haul bags of contraband salt into a train in defiance of the British monopoly their glass bangles break against the window bars.

The machine is introduced as a destructive force, often in conjunction with money. Thus we learn early on how drought turns Jaya’s ancestral country into a wasteland “to be exploited by the machines of a new age without customs or humanity.” Thus it is that the palace guru believes that by adopting the machines and institutions of the British, “we would adopt their ways, and in the process lose our souls.” Jaya’s father is shocked by the idea of investing money in stocks, for moneylending is undignified; it is against the dharma of a Rajput warrior. “Dungra’s thick lips, stained red with betel juice, opened in laughter. ‘Dignity? Dharma? You live in the past, Jai. Such words have lost their currency. Now the world runs on money.’ ”

Advertisement

The old world of customs and warriors against the new world of machines and moneylenders; no wonder at least one maharajah is said to have had portraits of Hitler in his study. He was not to know that Hitler, despite his love for Aryan nobility, was hardly interested in saving the Indian soul.

Jaya’s attitude toward the machine age is one of sad resignation:

She thought of her father’s mustache falling like a broken wing onto his white tunic as he told the Balmer Raj Guru that machines had ended the dharma of the warrior, and with it the dharma of the king.

For much of her life, inevitably for an Indian woman in the first half of this century, her destiny is controlled by men. They all represent something: her father, the old world Rajput; her husband, the confused, self-hating Anglicized playboy; her Indian lover, the Bengali babu nationalist; her English friend, the liberal who loves India. These are well-known types, but, as with Jaya, it is their ambivalence that saves them from being cardboard cutouts. For her father may be an old world Rajput, but he also tries to be modern, forcing his wife to break purdah and help the starving villagers during a famine. Osborne, the English friend, may be a liberal who loves India, but he remains loyal to his viceroy, to the point of spying on Jaya’s activities when he decides they are against British interests. And the Bengali babu, Arun Roy, is strongly drawn toward the very woman whose power he must destroy.

Sex is of course one of the most fascinating aspects of colonial society, the way sex became mixed up with politics. The early British settlers in India, soldiers and traders, employed by the East India Company, had no qualms about taking Indian mistresses; this was one of the “perks” of living in the tropics. But after the British began to rule India, not as traders but as a kind of superior caste, sex with the natives became a taboo, something upper-caste Hindus understood very well. The taboo was no doubt broken on some occasions, but this degraded the white sahib in Indian as well as British eyes. So even though every encounter between Jaya and Osborne is charged with erotic attraction, nothing happens, nothing can be allowed to happen. Even sex between the sahibs and memsahibs had to be discreet to maintain face in the eyes of the more fastidious natives. Nirad Chaudhuri, for one, was shocked by the sight of white couples carousing on Indian beaches, thereby “bringing disgrace upon the great European tradition of adultery established by all the historic adulteresses from Cleopatra to Madame de Stael.”2

The penchant among Indian aristocrats for seducing as many white women as they could was degrading in a different way. It was part of their playacting—collecting Hollywood starlets was not so different from collecting Hispano-Suizas. But it was also a kind of racial revenge, though the revenge was not as sweet as it should have been, for it was infused with self-hatred. Mehta catches this well in her description of Jaya as a new bride, still very much the traditional Rajput princess, pining for her absent husband. She asks her older friend and mentor, Lady Modi, otherwise known as Bapsy, why she appears to fill her husband with disgust:

“Is it the color of our skin? Our hair? Are white women so much more beautiful than we are?”

“Of course not, darling. It’s just that you represent everything the British Empire has taught Pratap and Victor to despise….”

So what should she do about it?

“If you want to attract your husband, Princess, you must make the British envy Pratap, not patronize him. You must make yourself into a woman who is desirable to white men.”

This still rings true today, from Bombay to Tokyo, where some women continue to have their eyes fixed to look more Western. Of course this is not for the benefit of Western males, who, in any case, tend to prefer exotic Asian beauty, but to suit their own notion that physically the West is best.

Jaya tries her best to dress like a European flapper, but never becomes the caricature that her cocktail-swilling friend Bapsy is. Nor does she become quite like Bapsy’s opposite, Jaya’s teacher, Mrs. Roy, a nationalist from Calcutta, dressed in white cotton saris; earnest where Bapsy is frivolous, loyal where Bapsy is fickle, intellectual where Bapsy is shallow. Jaya never becomes like Mrs. Roy, because she remains an aristocrat to the end, even when registering her name as a candidate in India’s first independent elections.

Jaya’s rebellion is not an intellectual one as Mrs. Roy’s is. She wanted to be a dutiful wife, but, rejected by her husband, she ends up hating him and everything he stands for. Refused his love, she gains his power. When she agrees to extricate him from a disastrous affair with an Anglo-Indian demimondaine formerly employed in a Calcutta brothel, she demands that she become regent of his state in the case of his death, which, as so often happens with shiftless playboys in novels, comes rather soon.

Advertisement

Gita Mehta’s novel is important because, for once, it deals with the Raj without nostalgia or bitterness. She is at her best when describing the twisted human relations in a colonial society. The first part of the story, Jaya’s childhood, interested me less than Jaya’s adult life. As a child she is only among Rajputs, with the occasional intrusion of a white man or a Bengali teacher. But it is in the milieu of nationalist radicals, Anglo-Indian mistresses, cynical politicians, decadent maharajahs, and Indian flappers that the novel really comes alive. It is, one feels, a milieu Mehta knows very well: that small, still-existing society in India, where East meets West, a sometimes fruitful, sometimes hilarious, sometimes disastrous encounter. The novel ends with Indira Gandhi’s parliamentary bill of 1970, discontinuing privy purses and abolishing the concept of rulership. It was the formal end of princely rule in India. But in few countries is the legacy of history, in spirit and form, so apparent as in India.

The worst legacy of modern colonialism, in India and elsewhere, has been the idea, very much in the foreground of Mehta’s novel, that superior race gave Europeans a divine right, even duty, to rule the world. It has left Westerners with a crippling sense of guilt, dangerously affecting their judgment of non-Western affairs. And it has left resentment and a confused sense of inferiority among the former colonial subjects. (The Japanese are a separate case; they tried to outdo the West by claiming they were the divine race destined to rule the world.)

But—and this is one of the strongest themes in Mehta’s book—it was the same West, with its machines and institutions, that inspired freedom and democracy, that broke the bangles of feudal bondage. The rhetoric of Indian nationalists was picked up in England, from the Fabians and the London School of Economics. The Bengali babus were in the vanguard of nationalist agitation because—unlike most of their British rulers—they were au courant with European ideas; they had read the books people read in London, Oxford, and Cambridge.

They were despised by the British for having done so, for acting above their station, imitating absurdly the ways of a superior race. The British much preferred Indians to remain exotic, hardy warriors, loyal Johnny Pathans and dependable Sikhs, colorful in dress, traditional in behavior. One of the paradoxes of the Raj, deeply confusing to educated Indians, is that the British encouraged emulation on the one hand and hated it on the other. They taught the Indian princes how to play cricket and sent them to English schools, but sniggered at the result: the half-baked Englishman, at home only in places like the Calcutta Turf Club. As Lord Curzon said about the princes at a gathering in 1902:

Amid the leveling tendency of the age and the inevitable monotony of government conducted upon scientific lines, they keep alive the traditions and customs, they sustain the virility, and they save from extinction the picturesqueness of ancient and noble races.

Note that word picturesque. Above all, India had to be picturesque and, of course, ancient—not so different from the attitude to Asia of the modern Western tourist, or even the well-meaning liberal: ancient and noble culture, not democracy, traditions, and customs, not the modern blight of materialism, machines, money. Under the Raj, the British took care of the money and the machines. And as long as the princes behaved traditionally, that is, as long as they were loyal to the British Crown, like feudal knights to their lords, they could have their champagne parties and golden cars. And it had to be said, those maharajahs threw some damned good parties.

It was the British, more than the Indians, who first attempted to define and preserve traditional India. This irony is often forgotten by writers who see Western colonialism only as an assault on traditional values. No doubt the Raj changed much in India (pace those who argue that it was nothing more than a swift ripple in the unchanging and largely inert ocean of Indian history), and all change is a challenge to what existed before. But it is a mistake to pit Western modernity (the machine) too neatly against the fragile glass bangles of Indian tradition. Indeed, some of the picturesque customs of India were of a British make.

Nirad Chaudhuri has pointed out how “the orientalism which became one of the two elements in the modern Indian synthesis, was not the native and traditional Sanskrit learning, but the new learning about the East created by the European orientalists.”3 And in his wonderful essay in The Invention of Tradition,4 Bernard S. Cohn writes how Victorian English-men fretted about the Indian “heritage.” They decided which monuments ought to be preserved, collected arts and crafts, translated classic texts, and compiled Indian history. “The British rulers,” writes Cohn,

were increasingly defining what was Indian in an official and “objective” sense. Indians had to look like Indians: before 1860 Indian soldiers as well as their European officers wore western-style uniforms; now the dress uniforms of Indians and English included turbans, sashes and tunics thought to be Mughal or Indian.

Injecting nationalist anthropology into politics was a popular idea in nineteenth-century Europe. That was what the Olympic Games were all about: the pageantry of man, each nation in its own uniform, singing its own lusty folk songs, waving its own banners. And this, on an imperial scale, is what the great durbars were about, when the British viceroy, or on one occasion the king-emperor himself, held court in Delhi, like the Mughal emperors before them, to the assembled aristocracy of India. The Indian princes were each issued their own coat of arms, designed by one Robert Taylor, a civil servant and amateur heraldist. Queen Victoria was proclaimed Kaiser-I-Hind in 1876, a brand new title suggested by G.W. Leitner, a professor of Oriental languages.

Cohn gives a hilarious description of the first Imperial Assemblage in Delhi, commemorating Victoria’s promotion to empress. Eighty-four thousand Indians and Europeans had pitched their tents over a space of five miles. On January 1, 1877, to the sounds of the “March of Tannhauser,” the viceroy Lord Lytton and his wife made their appearance, waving regally from their silver seat perched on top of the largest elephant in India, owned by the Rajah of Benares.

The point of all this is that the British deliberately used picturesque Indian tradition to strengthen their own power, creating a hierarchy of flags and banners, gathered like a great patchwork under the banner of the Kaiser-I-Hind. The diversity of race, religion, and languages of India, demonstrated at these jamborees, made it clear how unity was only possible under the “good government” of the British Crown.

This may not have been entirely a matter of playacting or cynical manipulation. Lord Curzon, like most people of his class and time, truly believed in tradition and customs and ancient and noble races. Certainly Benjamin Disraeli, the architect of British India and the prime mover behind that glorious Imperial Assembly of 1877, did. Hannah Arendt made the persuasive argument that Disraeli dazzled British aristocrats by promoting the myth of his ancient Jewish racial heritage, more ancient and far purer than that of the British aristocracy, which had seen too many infusions of new blood over the years. Race, said Disraeli, was the key to history, and there “is only one thing which makes a race and that is blood,” and there is only one aristocracy, the “aristocracy of nature,” which consists of “an unmixed race of a first-rate organization.”5 The first-rate organization, in his feverish imagination, was the British Empire and he, as a natural aristocrat, stood at its pinnacle with his beloved queen.

Racial pride, in the new scheme of things, was about all the Indian princes had left. The Rajput warrior, boasting of his ancient bloodlines, dazzled upper-class Englishmen in the same way Disraeli did. This is one reason, apart from the dashed good shooting parties, why the British still looked up to the princes, no matter how absurd their behavior, while despising the Bengali babus.

There was certainly an element of this in the British worship of Ranjitsinhji, Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, a famous cricketer before World War I. (Ranji, sometimes known as “the black prince,” makes a brief appearance in Mehta’s book, riding to King George’s durbar in a solid silver coach.) A.G. Gardener, one of Ranji’s British admirers, wrote a celebrated homage to the great cricketer, which is still recited in Indian schools:

The caste system of our own cricket field as of our own society has only the basis in riches. You cannot be a Runjeet Singh—to give the Jam Saheb the true rendering of his much abused name—unless you have the blood of the lion race in your veins, but you may join the old nobility of England if you have made a brilliant speculation in rubber….

Disraeli would have been amused.

So while the British machine helped to destroy the dharma of the warrior, as Jaya’s father lamented, the Raj may actually have helped to strengthen the mythology of warriorhood. The so-called martial races were the Indian corollary of the cold-bath-can-do spirit of the British White Man’s Burden. Many Indian princes outdid themselves to fight for the British Empire in both world wars. It was one way for Rajput warriors to retrieve their dharma, even though it quickly became apparent that, as Jaya’s father put it, “This is no war for men. It is a war between the mechanisms of slaughter.” The salvation of the Hindus, said Swami Vivekananda, who toured the US with great success in the 1890s, lay in three Bs: beef, biceps, and Bhagavad-Gita. It was his answer to the “muscular Christianity” of Dr. Arnold’s England. He said it, it is true, in a moment of despair about British colonial rule. But his response, to match the discipline (a key word of the Raj) and virility of the conquerer, with the same qualities, was typical. To add yet another irony to the history of the Raj, it was a decidedly unmartial Bengali intellectual, Subhas Chandra Bose, who finally gave political expression to militarism.

“Discipline,” said a Rajput rajah, showing me around early this year in the Rajastan desert, where Gita Mehta’s novel is set, “discipline is the only thing we learnt from the British worth learning, and Indians have lost that. No more discipline.”

One hears the same in Singapore and Malaysia: discipline and racial pride, the two prongs of British colonial ideology, are now part of postcolonial propaganda. Social Darwinism, largely discredited in the West, is very much alive in the minds of many Asian leaders. This is the final irony of the empire whose sun never set, that men like Lee Kuan Yew, who fought the British for their countries’ independence, now castigate the West for being flabby and decadent, for having forgotten discipline, pride, in short, the old White Man’s Burden. The “traditional values” of Singapore, touted as Confucian, are also the values of the Raj. The Darwinist ideas promoted by the likes of Malaysia’s prime minister Mahathir would have been warmly applauded by Rudyard Kipling.

Where does this leave the Indian princes, the Rajput descendants of Gita Mehta’s heroes? They seem as ambivalent as ever.

The rajah visitor pointed at the desert villages from his jeep: “Look around, life is just as it was before it was disturbed by the British.”

“How was it disturbed?”

He waved his hand dismissively: “Oh, they built electricity, railways, all that.”

“Was that a bad thing?”

“It was nothing at all. Look what has been achieved in forty years of independence. Compared to that the Raj was insignificant. They gave us some cars. A few Rolls Royces, here and there. But now we have our own Indian cars. We have airlines, we have nuclear power. Of that we are very, very proud.”

And so, a proud man, he returned to his palace, now a tourist hotel, where he received his guests with the courtesy one expects from a Rajput educated like an English gentleman at one of the former princely schools. Some of the lady guests, an Australian painter, a British schoolteacher, a French antique dealer, were dressed up in silk saris. One blond woman had daubed a red spot on her forehead, as though she were a Hindu. On her wrists glittered a mass of glass and silver bangles.

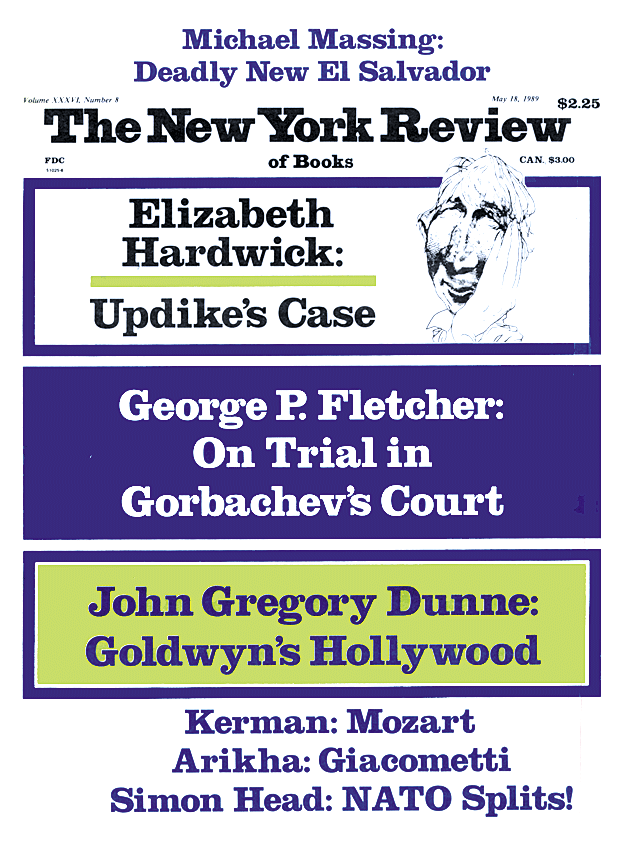

This Issue

May 18, 1989

-

1

Quoted from Gayatri Devi’s memoir: A Princess Remembers (1976). ↩

-

2

Thy Hand, Great Anarch! (Addison-Wesley, 1988), p. 167. ↩

-

3

The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian (University of California Press, 1951), p. 447. ↩

-

4

Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, eds., The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 1983). ↩

-

5

In Hannah Arendt, Antisemitism (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), p. 73. ↩