During the past decade in particular, the line separating fiction from autobiography has frequently seemed on the point of being almost erased. Novel after novel has appeared in which not only the background and chronology but also the major events of the first-person narrator’s life closely parallel what is publicly known of the author’s. The material is offered up uncooked, so to speak, without the subtlety and depth derived from imaginative transmuting of personal experience into fiction. the gains in journalistic immediacy are generally offset by the absence of the play of novelistic invention (a very different matter from autobiographical fibbing in the manner of Ford Madox Ford or Lillian Hellman).

Conversely, certain novels by writers of whom we know nothing except what is revealed on the dust jacket can have an autobiographical tone that at once distinguishes them from other realistically grounded stories in the first person that we unhesitatingly accept as fiction. One is not tempted to read The Catcher in the Rye as a largely factual account of an episode in J.D. Salinger’s adolescence. On the other hand, David Shields’s new novel, Dead Languages, which also deals with the experiences of a precocious, lively, but seriously troubled boy growing up in the Fifties, has the ring of experienced, autobiographical “truth.” The difference resides, I think, not so much in the voice of the narrators as in the books’ narrative shape. “All I’ve ever had are memories,” Jeremy Zorn, the narrator of Dead Languages, declares on the first page of the book. “No imagination, only memory.” The shape imposed by the dominance of memory over imagination (i.e., invention) affects the very sound and feel of Shields’s remarkable novel. (Of course every character and every event in Dead Languages may, for all I know, be entirely Shields’s invention; what counts is that the novel is written so as to make us feel we are in the presence of literal memory.)

Jeremy Zorn is a stutterer with the misfortune of having been born into an exceptionally articulate family. His mother, Annette, dominates the household. She is a journalist, a West Coast correspondent for The Nation and other left-liberal papers, a woman passionately concerned with the fate of the Hollywood Ten and causes supported by the ACLU, a tireless opponent of inquisatorial congressional committees, a crusading advocate of racial equality. But she is also a “Cossack” where her pathetic Jewish husband, Teddy, is concerned.

It was just not her way to rush to Father’s defense. She didn’t do that sort of thing. Father was so helpless he would have needed the Russian Army as a defense and, although Mother was the Russian Army, she was never especially prone to eliminating the enemy for him. Or, rather, she was the enemy for him. Why was she always so sweet to strangers and so tough on Father? I wish I knew.

Toward her son, she is superficially affectionate and subtly undermining. In later life, at the prodding of his speech therapist, Jeremy manages to evoke a scene from early childhood that may (or may not) represent the transition from slight to severe stuttering. Annette corners the little boy on the living room couch, pushes his hair off his forehead, blows smoke in his face, and attempts to have a heart-to-heart talk about his tendency to talk too fast and consequently to trip over certain words. (“Actually,” interjects the grown-up Jeremy, “studies show it’s not stutterers who talk too fast but the mothers of stutterers; it’s their fault.”) She tries to get him to say “Philadelphia” very slowly and carefully.

I tried. God knows I tried. But “Philadelphia” lay like dead weight on my chest, like helium in my head, neither light nor heavy, and yet with definite gravity to it: with downward pull…. Teeth on lips forever, and all I could come up with was an infinitely extended, infinitely painful Ffffffff. That’s all. Only that. Ffffffff. Nothing more.

“I don’t feel like saying that word right now,” I said.

“What word?” Mother asked.

“That word.”

“What word?”

“You know.”

“Give it a try.”

“No,” I said. “Not now. Maybe later.”

Mother shook her head in sadness and disgust.

Persistent, Annette produces stacks of flash cards and tries to get Jeremy to say what each picture depicts. He finds himself unable to call a single card.

Jeremy’s father is a highly emotional man, obsessed by the fate of the Rosenbergs and ever on the lookout for latent anti-Semitism. He jogs, plays tennis badly, umpires “industrial league” ball games in Golden Gate Park, and is much in demand for his ability to tell stories and Yiddish jokes. He is also a manic-depressive who is periodically driven off to a sanitarium for electroshock therapy. These parental figures, together with Jeremy’s precocious, fat, and unhappy sister, Beth, are portrayed with a brilliant mixture of pitiless observation, excoriation, humor, love, and forgiveness.

Advertisement

Dead Languages erratically follows the course of Jeremy’s growing up, from early childhood to approximately the age of twenty-one, when the young man, now a student at UCLA, must cope with his mother’s agonizing death. There is no episode in all of this time that does not reflect, in one way or another, his desperate need to escape the terrible sense of isolation induced by his stutter. “We all find some place we are powerful, though; we all go somewhere to be strong.” That is how Jeremy accounts for his father’s escape into sports, and how he would account for his own compensatory involvement in running and basketball, in editorial writing and school politics, and in his prepubescent and adolescent pursuit of unlikely girls. “Sometimes,” he reflects,

my childhood seems to me nothing more than an endless series of obsessions, overwrought attempts to get beyond a voice that bothered me and, like any saint in the grip of a metaphor, I desired either to vanish forever or to emerge triumphant.

Among the therapies he tries (designed to punish his mother as well as to mortify his own flesh) are total silence and fasting—both of which come to farcical conclusions. The comedy of Dead Languages equals (but never quite surpasses) its pain.

At one point, made frantic not only by his stutter but by the additional humiliation of acute acne, the boy makes an almost suicidal leap from a cliff to a sandy beach thirty feet below.

Right around the middle of good Aristotelian books, there’s supposed to be an action that reveals the protagonist’s hamartia—in this case…excessive self-absorption as a function of disfluency—and also transforms the rising action into falling action. But the cause of the falling action isn’t supposed to be quite so literally A FALL. It’s supposed to be a little more metaphorical than that. Still, I can’t alter the story of my life to conform to some archaic theory of dramatic structure.

Jeremy’s literal fall results in a broken thigh, but his comment applies to the non-Aristotelian structure of the novel as a whole. Not only is there no rising action; there is really nothing in the way of plot. Remembered episode succeeds remembered episode, and the reader for the most part is carried along by the vivacity of the language and moved by the unsparing, often hilarious, honesty with which Jeremy confronts himself and his family. We watch as the boy reaches for words, plays with them, achieves a nonoral mastery over them, and becomes a writer—a writer with an ineradicable sense of the inadequacy of his medium:

It’s an ancient story, beginning before Demosthenes, and it has a simple moral: we try to but cannot construct reality out of words. Catullus has nothing to say to the cab driver. A poem isn’t a person. Latin’s only a language. Stuttering’s only wasted sound. It can’t become communication.

Sandra [the speech therapist] strongly disagrees concerning the next point. She says personality disorders arise from stuttering whereas I seem to want to feel only the stutterer is faithful to human tension every time he talks, only in broken speech is the form of disfluency consonant with the chaos of the world’s content. Stutterers are truth-tellers; everyone else is lying. I know it’s insane but I believe that.

The book is wonderfully quotable. David Shields is an enviably talented writer, a stylist with a strong metaphoric gift and the ability to stage scenes of almost excruciating intensity. But I was sometimes exasperated by the obsessive, even repetitious quality of Jeremy’s preoccupations, and in the end I missed the pleasure of a fully imagined work in which the impulse to shape experience seems as strong as the impulse to reveal it.

By contrast, John Irving’s seventh novel is unmistakably a work of the imagination, with a distinct, if cumbersome, shape of its own. A Prayer for Owen Meany calls to mind a great galleon slowly ploughing its way, with much tacking and detouring, along an intricately plotted course toward its destined port. Irving, who sees himself as a neo-Dickensian, has, like Tom Wolfe in The Bonfire of the Vanities, chosen a sprawling, nineteenth-century model, whose principle is one of incorporation rather than of exclusion, a model designed to appeal to a diversified, nonacademic (but not frivolous) audience—in short, to whatever is left of that once large readership of bourgeois fiction. To induce its readers to undertake a voyage lasting more than five hundred pages, such a work needs what the narrator of A Prayer for Owen Meany calls a “bold beginning”—a subject on which he “harangues” his students in a course in Canadian literature. The bold (not to say loaded) beginning of this novel goes as follows:

Advertisement

I am doomed to remember a boy with a wrecked voice—not because of his voice, or because he was the smallest person I ever knew, or even because he was the instrument of my mother’s death, but because he is the reason I believe in God; I am a Christian because of Owen Meany.

The narrator is not only doomed to remember but, like the Ancient Mariner, to tell, in often exhaustive detail, the complex story sketched in that opening sentence, and in the course of the telling he attaches a dozen or more subplots to the major events.

The narrator is Johnny Wheelwright, born to a well-to-do New Hampshire family with roots going back to the earliest Puritan settlements. As a child he lives with his warm, attractive mother and his austere grandmother in a fine old Federal house in the town of Gravesend, which, like its prototype Exeter, contains a famous boys’ school. The odd thing about Johnny is his birth: he is illegitimate, the result of a “fling” which his otherwise respectable mother had with a man whom she met on the Boston & Maine Railway. Even after she marries, providing the boy with a kind and loving stepfather, she never tells her son who his real father is, and thus that old novelistic quest—the search for the father—becomes one of the more prominent subplots.

Johnny’s best friend is a strange, intense child,

who was so small that not only did his feet not touch the floor when he sat in his chair—his knees did not extend to the edge of his seat; therefore, his legs stuck out straight, like the legs of a doll. It was as if Owen Meany had been born without realistic joints.

Worse, the boy has a high-pitched voice that strikes people as both disturbing and uncanny. (Throughout the novel Owen’s dialogue, as well as his writing, is set in capital letters—a device that becomes not only distracting but tiresome.) But this Dickensian grotesque has a formidable intelligence, physical adroitness, and an impressive moral authority that is bolstered by his ardent Christian belief. The son of a lower-middle-class granite quarrier, Owen has inexplicably rejected his family’s Catholicism and become an Episcopalian. From a remarkably early age, he sees himself as God’s instrument and develops a quasi-Calvinist view of his life as predestined.

The manifold action of A Prayer for Owen Meany lends itself no more easily to summary than that of Bleak House, but two main events convey some of the melodramatic and even gothic aspects of the book. In the last inning of a Little League baseball game, the eleven-year-old Owen is asked to take Johnny’s turn at bat. He does so, hits the ball harder than he has ever hit it before, and the ball kills Johnny’s mother, who has befriended the boy and whom he dearly loves.

At Christmas that same year Owen plays the part of the Christ Child in a Nativity pageant and the part of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come in a production of A Christmas Carol. His performance in a rehearsal in the latter role is electrifying, and terrifies the actor playing Scrooge.

When Owen pointed [at Scrooge’s grave], it was all of a sudden, a convulsive, twitchy movement—his small, white hand flashing out of the folds of the cloak, which he flapped. He could glide slowly, like a skater running out of momentum; but he could also skitter with a bat’s repellent quickness.

On the night of the play’s opening, Owen, guiding Scrooge, approaches closer than before to the papier-mâché gravestone, bends over it—and faints. He has had a vision of his own name on the gravestone, together with the date of his death some sixteen years in the future. The possible fulfillment of this vision, augmented later by a detailed dream of the circumstances of Owen’s death, provides the main element of suspense for several hundred pages to come.

Giving and withholding, hinting and foreshadowing, Irving manipulates the elements of suspense as shamelessly as did his nineteenth-century master. As Dickens did, he flirts with the supernatural, especially in the form of precognition. Having aroused the reader’s curiosity concerning the fate of the main characters, Irving can indulge in various sideshows and diversions. We learn a great deal about the history of Gravesend and its illustrious academy, which both Johnny and Owen attend. We are treated at great length to the narrator’s opinions on Ronald Reagan and the contra scandal, the Vietnam War, American moral blindness, and contemporary Canadian literature. We are introduced to enough distinctively drawn characters to populate an entire village—among them the Congregational and Episcopalian ministers and their families, two headmasters of the Gravesend Academy, and assorted lesser masters, worthies and eccentrics and teen-agers of the town, Johnny’s boisterous male cousins and their angry sister Hester, the entire depraved family of a soldier killed in Vietnam….

But how interesting does John Irving make this material? Nowhere do we find the power, vision, or humor that would merit a comparison with Dickens. The Christian theme is obviously central to the novel, yet one is left in some doubt how it is to be taken. A Prayer for Owen Meany is steeped in the ritual and practice of mainline Protestantism, with frequent quotations of the familiar hymns and carols, and extended passages from Isaiah, the Gospels, and The Book of Common Prayer. Owen’s identification with the life and passion of Jesus Christ is presented, without a hint of irony, as lying at the very core of his behavior. Yet what the novel conveys is a sense of religiosity, rather than religion, of the miraculous rather than the spiritual. It is hard to give imaginative credence to Owen’s bizarre conviction without more to go on than the narrator’s reporting of his words and actions, especially since the narrator himself does not inspire total confidence. Too often the Christian elements seem merely another aspect of the novel’s sensationalism.

Admirers of The World According to Garp will, I think, find the new novel a lesser work—though it seems to me far stronger than either The Hotel New Hampshire or The Cider House Rules. Although it requires what for many will seem an inordinate suspension of disbelief, the story of Owen and his fate has a lurid power, especially in the novel’s final pages. Once he surrenders to the headlong rush of events, Irving shows himself a master of narrated action. But he is less successful in bringing his other major character, Johnny Wheelwright, to life in his own right, though nearly as much space is devoted to the narrator and his problems, sexual and otherwise, as to Owen. The fault seems to lie in the quality—at once overexplanatory and diffuse—of Johnny’s voice and the consequent blurring of the outlines of his personality. A number of the other characters, including the rather important figure of the grandmother, fail to transcend convenient stereotypes. Although the culmination of the extended set piece centering upon the Christmas pageant and play rises to a scream of (melo) dramatic intensity, the preliminaries are exhaustingly protracted and—to me—boring. Yet, despite this and other too frequent longueurs, many readers will probably read on. The power of raw curiosity to keep things moving is not to be underestimated.

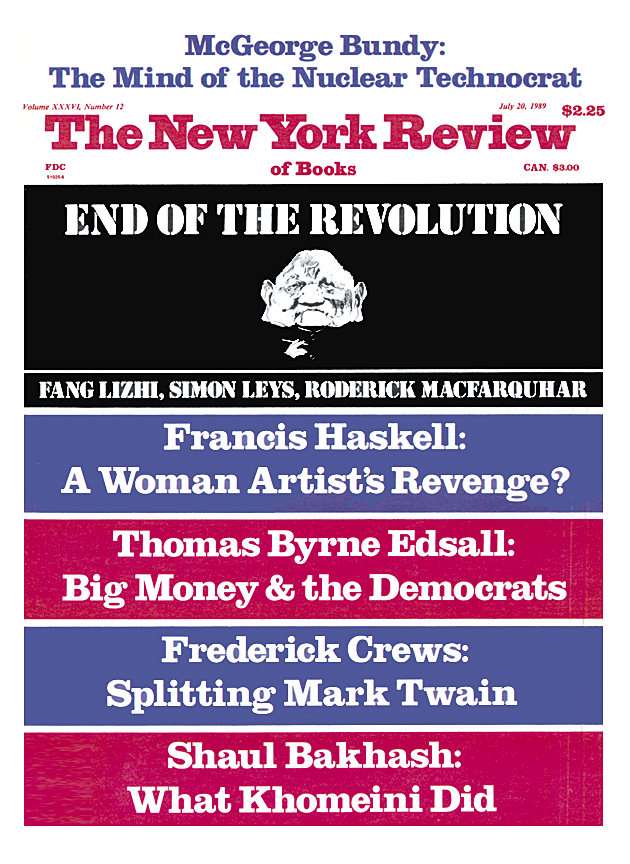

This Issue

July 20, 1989