A writer of the 1940s, R.G. Waldeck, said of the German princes who served as kings of Romania between 1866 and World War II that “they all went a bit haywire under the violent sun and deep blue skies. They could not take it. They overdid everything.” The Romanians themselves, she said, were “flexible, realistic fatalistic,” indestructibly enduring all with a conviction “of the transitory quality of everything.”

Yet the striking thing about the Romanians during the last half-year has been their abandonment of resignation and their superbly repeated demonstrations of defiance against the Ubu-esque regime that governs them in the guise of communism. This defiance of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu comes from within the upper circles of the Communist party itself, but, more formidably, it also comes from people entirely unprotected by privilege, established position, or the concern of the Soviet embassy. For example, the Cluj university teacher Doina Cornea, who addressed herself directly to Nicolae Ceausescu earlier this year in two letters published in the British press, and a third one broadcast by Radio Free Europe; she also testified against the Ceausescus in an interview on Belgian television. Six citizens of Cluj and Zarnesti, and of Poiana village, countersigned their names and her second letter to the London Spectator.

There is the poet Mircea Dinescu, who gave a sardonic account of Romania’s condition to the Paris newspaper Libération in March. Nicu Stancescu, a hydraulic engineer and Party member who is now compelled to work as a farm laborer, wrote to the French press in May about “the generalized crisis” in the country and the “skepticism and apathy of the population.” In January, three prominent journalists and a printer published an anti-Ceausescu manifesto, and were arrested. Several other writers have made public declarations critical of the government’s policies; measures of retaliation against them have provoked still other protests by members of the Writers’ Union, including people previously close to the government as well as writers who have never been members of the Party.

Politically, the most significant of the protests was that delivered to Nicolae Ceausescu in March by six veteran members of the Romanian Communist party, including one of its founders. (The text was published in The New York Review of Books of April 27.) They said the government has demonstrated its inability to solve the basic economic and social problems of the country, and that it even threatens “the biological existence of our nation” by its fanatical export program and simultaneous wrecking (“systematization”) of the rural economy. The latter program destroys traditional villages in order to rehouse peasants in apartment blocks and reestablish rural life on an industrialized basis. At least twenty-nine villages have thus far been demolished in this way, and destruction has begun in another thirty-seven, according to the historian Dinu Giurescu, who was until 1985 a member of the Romanian Central Commission of the National Patrimony.

Many of the recent dissidents have been arrested and interrogated. Some have been put under house arrest. Others have been deprived of their houses or apartments or forcibly relocated to the countryside—internal exile. People have been molested or attacked in the street by “unknowns,” as has also happened to foreign diplomats and reporters attempting to make contact with dissidents. Criminal or civil charges have been brought against some. Thus the poet Dan Desliu has been accused of black marketeering. A former Politburo member, Alexandru Birladeanu, a signer of the “Letter of the Six,” is accused of trafficking in video recorders.

People have lost their jobs and apartments; writers have had book and magazine agreements cancelled. The dissidents have been isolated, mail and telephones cut off. Colleagues of the arrested journalists have been dismissed for privately expressing their sympathy for the dissidents. Some employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were dismissed simply because they had worked with the dissidents in the past. The government has retaliated against members of their families. It brought charges of treason and espionage against Mircea Raceanu, a diplomat, once at the Washington embassy, who is the adopted son of one of the signers of the Letter of the Six, Grigore Raceanu. The daughter of another signer, Silviu Brucan, was dismissed from the post she held for twenty years with Romanian television, and his son-in-law, an architect, has been forced to leave Bucharest for an assignment in the provinces. The special medical treatment that Mr. Brucan, who is in poor health, is entitled to as a veteran of the wartime resistance has been withdrawn, and he has been forced out of his apartment in Bucharest to relocate in a place without running water or heat.

An observer inside Romania remarks that these forms of repression are designed to avoid the overt violations of human rights that attract Western attention, while producing the same results through an accumulation of lesser forms of punishment, “which in their ensemble can have the gravest consequences for those who have to bear them.” Yet the regime’s comparative restraint is significant. No one has so far been shot; no one has (as yet) disappeared. The dissidents’ lives have been made exceedingly unpleasant, but they survive and maintain their defiance. The government’s actions reveal a fear that recent events could have consequences they would want to avoid.

Advertisement

Time ends even the most awful regimes. Intensifying internal propaganda in Romania on nationalist themes is clearly defensive. Nicolae Ceausescu is seventy-one and reported to be seriously ill. The Party he leads is divided. The Soviet Union wants him and his wife out of power. Hungary is openly hostile because of Romania’s policy of forced cultural assimilation of the approximately two million ethnic Hungarians in Transylvania (some 20,000 of whom have fled to Hungary since 1987, an exodus that continues). Western pressures on Ceausescu’s government are now strong, although not as strong as they might be. The Norwegians, Danes, and Portuguese have closed their embassies.

Citroën of France and Rank AG of West Germany have ended or are about to end joint industrial ventures with Romanian government enterprises; another joint venture by an Italian company is in difficulty. The Financial Times says that the only remaining joint enterprises of any consequence are with Control Data of the US and a British avionics company. President Ceausescu himself concedes that only half of Romania’s current export contracts are now being fulfilled. The problems are the usual ones: the abysmal quality of what is produced, the incoherent or incompetent management, the miserable standard of living suffered by the workers and their resulting lack of motivation. Industry is starved of investment. The people during the last few years have been starved of food. The ground on which the despot stands is arid, cracked. The violent sun shines down. There is hope for Romania.

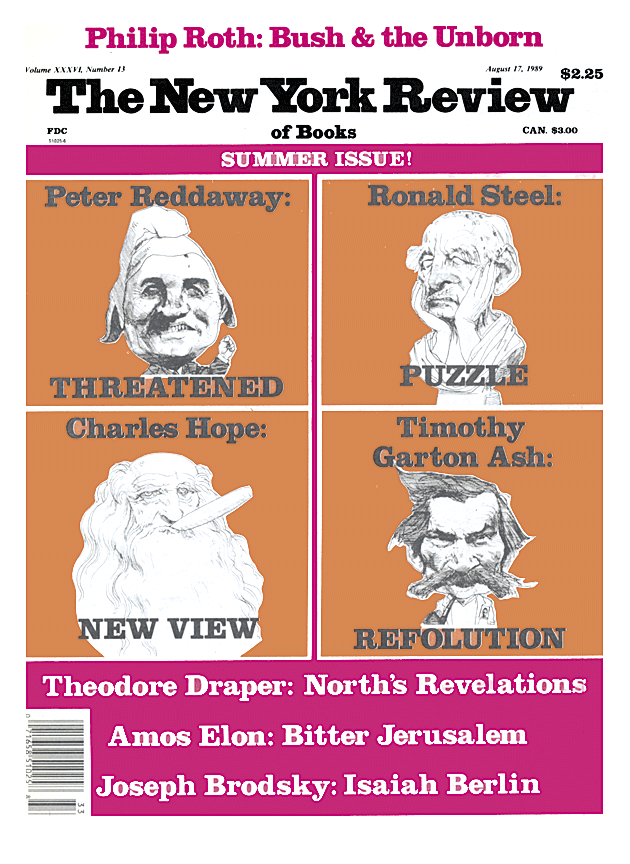

This Issue

August 17, 1989