For Olivier on his 21st birthday

Olivier, your father and I have known each other since I was eighteen and he was thirty-one and I always associate him with hilarious moments. None was more hilarious than our visit to the Soviet Union which coincided with your arrival.

You will have been told a thousand times how your great-grandfather was a Bolivian hacendero, who, one day, found two American trespassers with bags of mineral specimens on their backs. He locked them in a stable, thinking the minerals might be gold or silver. Finally they confessed the specimens were tin. That is one side of your family history.

In the spring, twenty-one years ago, your father learned that I had an official invitation to visit archaeological museums in the Soviet Union and also to meet Soviet archaeologists. The man who invited me I had met the year before in Sofia where I assured him that a treasury supposed to have been found at Troy, was either a fake or a fake on paper. The rest of the party was to include my professor of archaeology and a lady Marxist archaeological student from Hampstead.

We met in Leningrad. G.O. was Doctor O of the Basel Museum. For the first days he behaved like Dr. O. He listened patiently—although he nearly exploded afterward—to the rantings of an orthodox Marxist archaeologist. The museum impressed him greatly. He saw Greek objects, but he saw objects he had never seen before, treasures from the frozen tombs of Siberia, objects from the Siberian taiga.

On our last day in Leningrad we had an interview with the deputy director of the Hermitage Museum. The director himself was away in Armenia excavating the site of Urartu. It would not be fair to say that your father reached the door handle, but he is not a tall man, and the space suited him ideally. We were, after all, in the Tsar’s reception room. The Deputy Director greeted us with great kindness, but was plainly quite shocked by his previous visitor. As we entered a notorious peddler of fakes from Madison Avenue went out. He had told the deputy director, in the name of his own foundation for the investigation of forgeries, that the celebrated Peter the Great Gold Treasure had been made by a jeweler in Odessa in 1898. Your father rose to the occasion and assured the man that his visitor had been a complete fraud. He then got carried away. The mask of Dr. O vanished. He said, “This is the greatest museum in the world, right? I am the greatest collector of Greek bronzes in the world. If I leave you my collection in my will, will you appoint me director of this museum for a number of years?”

We went on to Moscow and stayed at the Metropol Hotel. Dr. O reasserted his identity. Again, in the Russian Historical Museum, he saw objects he had never dreamed of. We went to a reception to meet seventy Soviet scholars and had to stand in line having our hands crushed. Our host, the top archaeologist of the Soviet Union and my friend from Sofia, was there to greet us. By the window, G.O. and I saw a pair of very cheerful figures looking at us with amusement. I said, “One is an Armenian, the other a Georgian.” When our fingers stopped being crushed, we went over to these two gentlemen. I was right about the Armenian. The other, with a huge black mustache, was a Greek from Central Asia. I asked what they were laughing about. They said they had just been paid for their doctoral thesis and were deciding if they had enough money to go to the Moscow food market and buy a whole sheep for a barbeque.

G.O. passed the test of being a great Greek scholar. On our last evening in Moscow we were invited by the top archaeologist himself to an Uzbeg banquet. The only dish was a lamb stuffed with rice, apricots, and spices. The whole party became extremely drunk on wine, on champagne, and, worst of all, on brandy. I was very drunk myself, but threw every second glass on to the floor. The Soviet academicians went under the table one by one. G.O., the Marxist lady archaeologist, and the professor went off to the lavatory and were sick. The top archaeologist, in a steel gray suit, was drunk and the only survivor except for his sister with whom he lived, and who did not drink. She asked me to recite speeches from Shakespeare. I stood up:

“If music be the food of love, play on,

Give me excess of it; that surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.

That strain again, it had a dying fall;

O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound

That breathes upon a bank of violets.”

. . . “The quality of mercy is not strain’d…”

. . . “I come to wive it wealthily in Padua;

If wealthily, then happily in Padua.”

. . . “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead.

In peace there’s nothing so becomes a man

As modest stillness and humility;

But when the blast of war blows in our ears

Then summon up the action of a tiger;

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood,

Disguise fair nature with hard- favor’d rage.”

The top archaeologist finally went under the table like a gray sea lion who could stand the open air no longer. It was time to go. The Western party had revived. I was still very drunk.

Advertisement

In Moscow it was the time of white nights. A large Volga limousine taxi appeared to be waiting for us. We drove back to the hotel. I lay down on the bed, which was furthest from the bathroom. “You were wonderful,” said your father. “You showed them what Englishmen are made of.”

“Look, I’m going to be sick. Get the woman to bring a basin.”

“Now I know why England won the war.”

“Get me a basin, quickly!”

“Do you think I should send my son to Eton?”

“Watch out,” I cried—and a column of vomit fell diagonally across his bed.

“Look what you’ve done to my Charvet dressing-gown!”

I think this was the end of the Soviet Union for your father. He survived a day in Kiev but his thoughts were on Catherine and your birth. I feel I should record this on paper and offer it to you as a twenty-first birthday present.

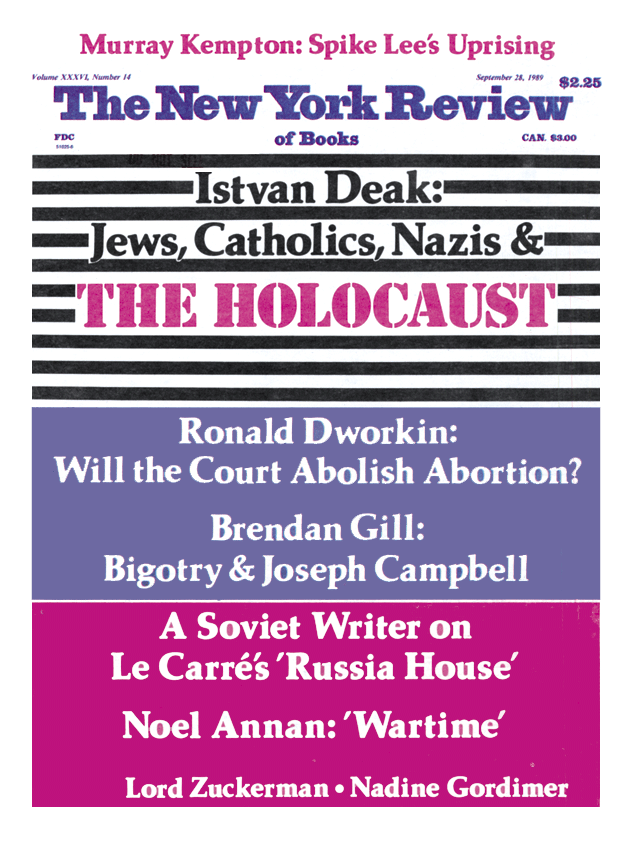

This Issue

September 28, 1989