In response to:

The Legend of King Christian: An Exchange from the March 29, 1990 issue

To the Editors:

It comes as a terrible shock to realize that enough time has passed for the exploits of King Christian of Denmark to have entered the realm of the quasi-mythical [“The Legend of King Christian: An Exchange,” NYR, March 29]. As a sergeant in the 29th Infantry Division stationed in the Bremen enclave at the end of the war, I went to Denmark to record the history of the Danish Resistance and to interview its leaders. Although I was in Field Artillery, I had been a newspaperman and considered qualified. It was in no way official although some of my findings were published.

Even at that time when the king was still alive there were many apocryphal stories regarding his role, and he made every effort to deny them. I can definitely state he did not wear a six-pointed star because at no time were the Jews required to wear one.

Denmark capitulated after a few brief skirmishes and a few deaths. The country did not have an army to stand up to the powerful panzer divisions nor did the rolling pasture lands lend themselves to defense. Apparently by terms of the capitulation, the Gestapo was not to be introduced into the country nor were there to be anti-Jewish laws. This did not deter the Danish Nazis who were emboldened by the German presence. To prevent harm to the Synagogue, men of the congregation patrolled the synagogue environs and had communication to the Danish police. Attempts to burn the building were thus frustrated.

Although the Danes were fairly well-treated they resented the Nazi presence and referred to themselves as Hitler’s Canary. After all, the Danes were like all Scandinavians, Super-Aryans and were not to be crushed like Slavic untermenschen. Because of growing resistance, particularly along the railroad to Norway, the Germans decided after two years to empower the Gestapo to become active. One of the first measures was to introduce the racial laws with the Jews wearing the yellow star.

When the king was thus informed, he announced that if any of his subject were humiliated in any way, he would join them and this included the wearing of the Star. The Germans, more dependent upon Danish farm products and particularly animal fats, rescinded the order. Another story based in fact was the opposition of the king to the flying of the Swastika above the City Hall. If it was not lowered he would send a Danish soldier to take it down and when the Nazi commander informed him that the soldier would be shot, the king announced he would be the Danish soldier they would have to shoot.

One story the king vehemently denied was the charge that German soldiers were responsible for the permanent injuries he had received when thrown from his horse. It was his custom to ride every morning through the parks, and he was roundly cheered by the people who gathered to show their loyalty. It was on one such occasion the horse was frightened by the cheers and threw him. The story was that German officers had revved the motor of a vehicle so that the horse was startled. Whenever I saw him in those days he was in a wheel chair. The last occasion was the rededication of K-B Hall which the Germans had used as a detention center.

When word was passed through community leaders for the Jews to repair to the ports where the fishing fleet had been mobilized to take them to Sweden, the residents of the Old Peoples Homes were forgotten. They were the ones rounded up and transported to Theresienstadt where the Swedish Red Cross under Count Folke Bernadotte looked out for their welfare. These buildings the old people were taken from were thoroughly looted and when they returned the furniture had disappeared—thanks to the German army. The abandoned homes of individual Jews had the furniture dispersed among neighbors and brought back upon their return.

If I remember correctly only twelve of the old people died at Theresienstadt and that from natural causes. On the other hand, of the several thousand Norwegian Jews rounded up, only twelve survived.

Upon the arrival of the Gestapo, agents were sent to the Synagogue to procure the Scrolls of the Law. The Sexton, Karl Christensen, a non-Jew, said he did not have a key but if they would return in the afternoon, he would have one for them. He immediately took the Scrolls to the Bishop, who hid them in the Cathedral, and when the Gestapo returned, he told them he was under the impression they had ordered him to burn the scrolls. Upon liberation the Bishop and Crown Prince carried the Scrolls toward the Synagogue. Halfway they were met by the Chief Rabbi of Denmark and other members of the Royal Family who then carried the Scrolls back to the Synagogue. It was one of those magnificent moments that followed the war.

Advertisement

The German method of punishing the Danes for Resistance was very different than followed in Poland. When Kai Munk, the great Danish writer, was killed by the Gestapo, mourning was forbidden. The Danish store windows were emptied of all contents and a black square was substituted. Punishments for other acts were a bomb in the vats of the Tuborg Brewery, closing of the Tivoli gardens, etc.

However, no mercy was shown the active resistance. It was Froslev or the firing squad or gallows.

Hitler’s canary was really a fabled phoenix.

Leonard Mendes Nathan

Chicago, Illinois

To the Editors:

I thought you and Jens Lund would be interested in the enclosed exchange of correspondence.

Her Majesty Queen Margaret II

Your Majesty:

I feel constrained to begin by reintroducing myself. I sat next to you at a dinner given in Megève as guests of Mr. & Mrs. Bernard de Ganay approximately one decade ago. During our dinner conversation I remarked how admirable was the conduct of His Majesty King Christian in stories I had heard about him at the time of the German occupation of Denmark during World War II. I recall your telling me that the conduct attributed to His Majesty King Christian in the stories was indeed admirable but, unfortunately, that the stories were not true! The depth of my disappointment was exceeded only by my respect for your candor.

In that connection, I thought you might be interested in the enclosed piece which appeared in the March 29, 1990 issue of The New York Review on the very same subject.

I have just had the pleasure of returning from my one week visit to the one-time Danish island of St. John, now a part of the US Virgin Islands—so that there was yet one more reason for me to think of Denmark when reading the enclosed article.

James B. Sitrick

New York City

Dear Sir:

Her Majesty the Queen has duly received your letter of March 26 with enclosed copy of The New York Review. By Royal command I have the honour to answer your letter.

The facts about King Christian’s attitude towards the Jews are following:

- In 1933, after Hitler’s take-over, the King attended a service in the synagogue.

- In 1941, after the German occupation, the King in a personal letter condoled the Jewish community due to a fire in the synagogue.

- In October 1943 the King in a personal letter to Adolf Hitler warned him against interning the Danish Jews.

King Christian never wore the David Star and nothing is related for sure that he eventually threatened to do so.

Thus Mr. Jens Lund’s article on the whole is well founded. However, it contains other errors.

Sixteen Danish soldiers, not one hundred, were killed on April 9, 1940. The Minister of Transport mentioned was not appointed till July 8, 1940, and neither he nor the Director General of the Danish State Railways had anything to do facilitating the Germans in securing control of the Danish countryside. Danish defence was in a bad condition—as in all other European countries apart from Germany. After a few hours of shooting the government surrendered. At that time this was generally considered the only thing to do. Later opinion changed.

Tage Kaarsted

Historiographer to HM the Queen

Copenhagen, Denmark

István Deák replies:

The exchanges with readers which have appeared since my review “The Incomprehensible Holocaust” [NYR, September 28, 1989] have concerned mainly the responsibility of the Catholic Church and of the East European peoples. Lately, however, Denmark and its king have also entered the picture, the question being what price that country and the anti-Nazi cause in general had to pay for the Danes’ unique success in assuring the survival of the Danish Jews. During his stay in Denmark, Leonard Mendes Nathan heard a mixture of fact and fiction of the kind that has characterized virtually all stories about collaboration and resistance.

Despite all the sympathy the Danish government later showed for the victims of Nazism, it had, during the 1930s, followed the example of practically all other Western governments in making its immigration laws gradually more restrictive. No more than 4,500 Jewish refugees were allowed into the country, generally not to settle, but to use Denmark as a way station.

The Nazis regarded the Danes as quintessential Aryans, and although Denmark had a sizable German minority, Danish National Socialists received at most 2 percent of the votes, even during the 1943 parliamentary elections held under German occupation.

On April 9, 1940, when two German divisions invaded Denmark, the armed forces of that country numbered fewer than fifteen thousand men, mostly untrained recruits, who were widely scattered in the countryside. This was about one half of the forces available when the European war broke out in September 1939. In the words of the historian Richard Petrow, Denmark earned “the dubious distinction of being the only country in Europe to weaken its defenses at a time when the danger to the country was growing.”1

The Danish navy surrendered without firing a shot, but the ground forces put up some symbolic resistance; perhaps sixteen Danish soldiers were killed, as the letter from the Queen’s historiographer published above confirms. German casualties amounted to twenty soldiers killed and wounded. In view of the German army’s and navy’s visible preparation in the spring of 1940 for aggressive campaigning, the weakening of defenses was nothing short of scandalous, especially since the 3.8 million Danes could easily have mustered a well-trained and well-equipped force of several hundred thousand. Wasn’t Denmark one of the richest countries in Europe, and weren’t the Danish youth eminently healthy and loyal? Western historians and journalists have never ceased to criticize the unreadiness of the Polish army in September of 1939, and the Polish cavalry’s suicidal attacks on the German Panzer. They might, for once, take notice of the far graver unreadiness, eight months after the invasion of Poland, of the neutral Danish, Norwegian, Dutch, and Belgian armies. Apparently, criminal lack of preparedness is a meritorious trait only when practiced by peace-loving, small, West European nations, but a mark of arrogance and foolishness in the case of East Europeans.

Advertisement

Following the invasion, Denmark was occupied by a single German infantry division and even that division was withdrawn, in May 1940, to participate in the campaign against France and the Low Countries. Allowed to retain its king, ministry, parliament, political parties, army, and police forces, Denmark was supervised by eighty-five German civilian officials and an additional 130 employees. In January 1941, Denmark handed over six new torpedo boats to the German navy, and on November 25, it joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, thereby abandoning neutrality, which it had refused to give up in favor of France and Great Britain before the German invasion. Denmark was now legally, if not necessarily in practice, a German ally, and formed, next to the Czech lands, the other “model Protectorate” in German-occupied Europe.

Things changed drastically, however, in the spring of 1943 when the Danish left-wing parties and unions, particularly the Social Democrats, began to engage in active resistance. In August, for instance, a strike of dockworkers paralyzed Odense harbor. In response, a state of emergency was proclaimed, the Danish army was dissolved, and the king was temporarily placed under house arrest, thus enabling the Nazis to institute their program of deporting the Jews.

The target date for forcing the Jews to leave was set for October 1. From the beginning, however, everything seemed to go wrong for Heinrich Himmler, who had initiated the deportation measures, Georg Ferdinand Dubowitz, the German legation attaché and resident Abwehr agent, later to be honored in Israel as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations,” leaked the news of the German Aktion to his Social Democratic friends. Dr. Karl Werner Best, the Reich Plenipotentiary and SS General sent to Denmark in 1942 to replace the far too meek German minister, procrastinated a great deal. Among other things, he forbade the German police to break into apartments; they could arrest only such Jews who answered the doorbell. But most Jews had been forewarned by the resistance and had gone into hiding. During the next few weeks, Danish Lutheran bishops, trade union leaders, politicians, boy scouts, university students, and the police rallied to spirit the Jews to the Danish harbors, from which they were shipped across the sea to Sweden. Local German soldiers, including the German naval command at Copenhagen, preferred to look the other way during the operation.

Some 7,200 people, Jews, half-Jews, and their Christian spouses, made it to freedom. Fewer than five hundred were taken to the model camp of Theresienstadt in Bohemia, where again all survived except for about seventy old deportees. No Danish Jew was killed, and none deported to Auschwitz, which was the ultimate fate of most other Theresienstadt inmates.

Still, the paradoxes of the Danish situation do not end here. Toward the end of the war the Germans decided to allow a Danish Red Cross delegation to visit the Danish Jews at Theresienstadt. To relieve overcrowding and to make a better impression on the visitors, Adolf Eichmann deported thousands of non-Danish Jews from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz, there to be gassed. When the Red Cross representatives arrived on June 23, 1944, they found a truly model camp there. Well provided with food parcels from home, the Danish Jews presented a heartening picture to the visitors who were, in any case, more than willing to believe the Germans. In a subsequent thank-you note to the German Foreign Office, the Danish minister to Berlin declared that the delegation had been delighted with the hospital and the Jewish theater.2 Thus, while such myths as King Christian X wearing the Yellow Star (or his having declared he would wear it, or his threat that he would personally haul down the Swastika flying above City Hall), have done much to obscure our image of the West European behavior toward the Jews, that visit to the Danish model camp at Theresienstadt, which may have inadvertently caused many deaths, helped to obfuscate the contemporary perception of the Final Solution.

Finally, in April 1945, when thousands of other Jews were dying in the camps or on forced marches, the German authorities sent all the Danish Jews from Theresienstadt to Sweden. The rescue of the Danish Jews, never more than 0.2 percent of the Danish population, was complete.

Powerfully supported by the British, the Danish resistance became even more active in 1944, with regular street battles fought in Copenhagen. Many members of the resistance, including two thousand policemen, were deported to concentration camps. At the end of the war, the triumphant resistance movement hunted down collaborationists: twenty thousand were arrested, more than thirteen thousand received prison sentences, and forty-six were executed.

Danish behavior toward the Jews was admirable, but the price to be paid for the rescue was economic and political collaboration. Such other collaborationist regimes as the ones in Bulgaria and Italy did almost as well in aiding Jews, often in far more difficult conditions, and the Bulgarian metropolitans Stefan and Cyril, and the Italian generals Giuseppe Pièche, Mario Roatta, and Giuseppe Amico (the latter was killed by the Germans for his efforts) deserve as much praise as the best of the Danish leaders. Their humane actions, and those of thousands of other priests, officers, diplomats, and ordinary people are part of a glorious historical record, of which much more ought to be written. Theirs was the spirit of Lutheran Bishop Fuglsang-Damgaard at Copenhagen who, following the German Kristallnacht in November 1938, instructed his pastors to pray for the Jews and “to protect our people against the poisonous pestilence of anti-Semitism, hatred of the Jews and persecution of Jews. Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ was David’s Son after the flesh, and those who love Him cannot hate His people.”3

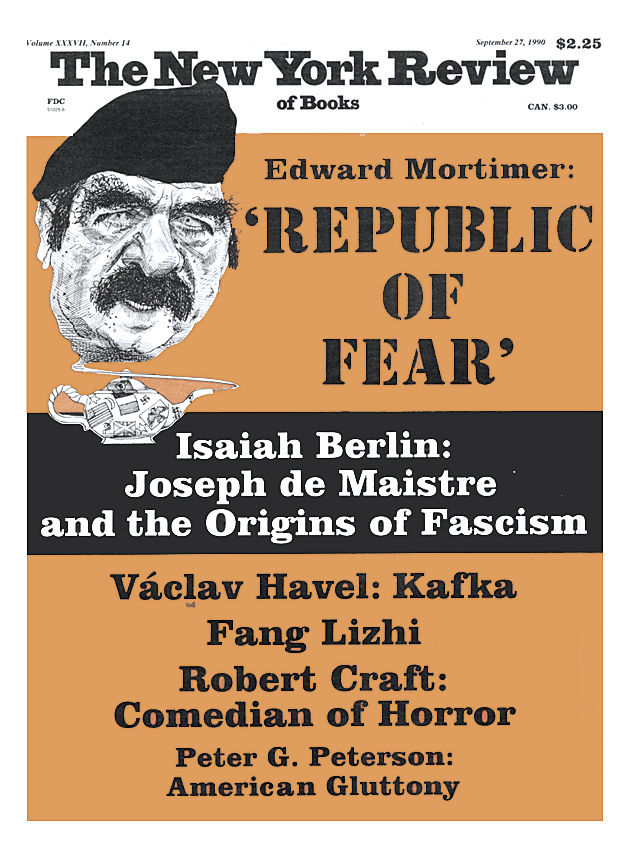

This Issue

September 27, 1990

-

1

Richard Petrow, The Bitter Years: The Invasion and Occupation of Denmark and Norway, April 1940–May 1945 (Morrow, 1974), p. 45. ↩

-

2

On this, see Gerald Reitlinger, The Final Solution: The Attempt to Exterminate the Jews of Europe, 1939–1945 (A.S. Barnes, 1961), pp. 170–173. Also, Petrow, pp. 307–313. ↩

-

3

Cited in Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide: National Responses and Jewish Victimization during the Holocaust (University of Chicago Press, 1979), p. 125. ↩