Ronald Reagan is a lethally nice man. Pursuit of him takes one up above the Ike line of mere amiability into a rarefied atmosphere that is too sweet for his enemies to breathe. He is so courtly, in a quaint and old-world way, that he still cannot bring himself to use all the four letters of a four-letter word like h—l. He likes to be liked, and cannot conceive that anyone might dislike him. His own virtue is self-evident. Merely to proclaim it is to prove it. There is no doubting his sincerity:

In 1987, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall gave a television interview in which he implied I was a racist…. A meeting was arranged between the two of us.

We spoke for an hour or so upstairs in the family quarters, and I literally told him my life story—how Jack and Nelle had raised me from the time I was a child to believe racial and religious discrimination was the worst sin in the world…. That night, I think I made a friend.

The power of the reconteur is the theme of this book. At the Williamsburg economic summit,

Someone—I believe it was Helmut Kohl, who had replaced [Helmut] Schmidt as chancellor of West Germany—spoke up: “Tell us about the American miracle….” I launched into what I guess was a variation of the speech I’d been making for years…. Everyone around the table just listened in silence as I spoke. It wasn’t long after that that I began reading about a wave of tax cutting in several of their countries.

When the rare auditor does not believe Reagan as he tells his miracle stories, he thinks there is something perverse in that person’s makeup. His anger at Reykjavík came over Gorbachev’s unwillingness to believe that Reagan meant SDI only as a peaceful development he would share with the world:

Privately, I had made a decision: I was going to offer to share SDI technology with the Soviets. This, I thought, should convince them it would never be a threat to them…. No country would do that, he [Gorbachev] insisted, judging others by his own country.

That others could doubt his country’s virtue was as puzzling as any doubts about his own luminous rectitude:

I’d always felt that from our deeds it must be clear to anyone that Americans were a moral people who starting at the birth of our nation had always used our power only as a force of good in the world.

This is a thought to which Reagan repeatedly returns:

The United States, when it could have dominated the world with no risk to itself, made no effort whatsoever to do so,…the United States followed a different course—one unique in all the history of mankind. We used our power and wealth to rebuild the war-ravaged economies of the world, including those nations who had been our enemies.

This altruistic action was splendid in Reagan’s eyes because we were helping foreigners who have, apparently, no moral fiber to be destroyed. It is only when our government helps Americans that its altruism is misguided. Told that America had its critics in Europe, Reagan responded to Helmut Kohl:

We were the most moral and generous people on earth…. It was clear we’d have to do a better job of conveying to the world our sense of morality.

When asked by parents of the marines who died in Lebanon for an explanation of their deaths, Reagan replied:

America is a country whose people have always believed we had a special responsibility to try to bring peace and democracy to others in the world.

How did America pull off its economic miracle under Reagan? This occured because “There is a moral fiber running through our people.” Some see the 1980s as a time of greed and plunder. It looked different to Reagan:

I hope history will look back on the Eighties not only as a period of economic recovery and a time when we put the brakes on the growth of government, but as a time of fundamental change for our economy and a resurgence of the American spirit of generosity that touched off an unprecedented outpouring of good deeds.

As a country “we are unbeatable at whatever we do.” Our country is all but obsessed with doing good: “Americans have always accepted a special responsibility to help others achieve and preserve the democratic freedoms we enjoy.”

The thing that makes us so virtuous is our free-market system. Capitalists are the best expression of this freedom and virtue, and turning over the government to them was the secret of Reagan’s success as governor of California and president of the United States:

I called some of the leading business people in California together at a luncheon, told them what I had in mind, and said, I’ll leave it up to you. You tell me how we can make our state government work better.

Convinced of his success at the local level, he took the same approach to Washington:

Advertisement

A lot of the reductions resulted from simply giving government workers the opportunity and tools to operate as efficiently as their counterparts in the private business world. In 1982, I asked J. Peter Grace, chief executive of W.R. Grace & Company and a Democrat, to establish a panel of top businessmen to study federal operations and recommend how we could reduce waste and make the government more efficient. The Grace Commission—also known as the Private Sector Survey on Cost Control—was patterned after that panel of businessmen I’d appointed when I was governor to streamline the government of California. The idea had worked in Sacramento; why not in Washington?

Reagan does not tell us that he early turned over his own private finances to “a panel of businessmen” who made him a millionaire, built him tax shelters, and supplied him with houses and expensive presents. The largesse that corrupts the poor he could accept as the tribute one kind of virtue pays another. He turned government over to these same altruists, certain they would contribute much and take nothing, acting as our country does in its dealings with others.

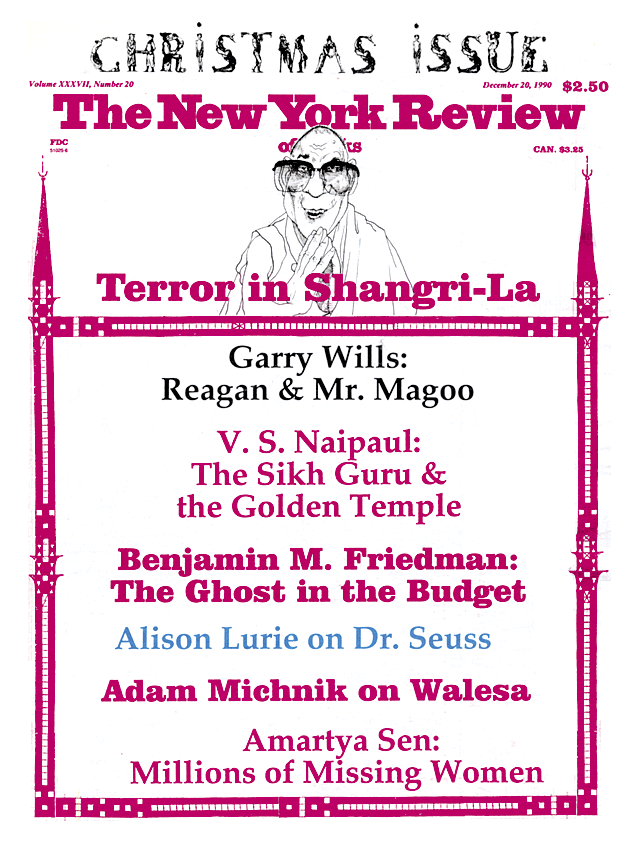

The cartoon character Mr. Magoo, blind and optimistic, loudly describes the happy things going on around him while the viewer sees him surrounded by perils, destruction, and violence. So while Reagan fondly described his period as one continual sequence of virtuous acts, businesses were taking corruption in defense contracts to spectacular new heights, robbing the HUD treasury, and using government-backed savings and loan banks as their private kitties. Is Reagan incapable of seeing such things? That seems to be the case.

People and events come to Reagan wearing labels that place them securely in his morality play. Life is for him an exercise in type-casting. Entrepreneurs are always brave and generous, bureaucrats timorous and obstructive. The labels are spelled out in large letters, the only type size Mr. Magoo can, with an effort, make out.

[Jesse] Unruh was a classic tax-and-spend liberal.

Walter Mondale…was another classic tax-and-spend liberal….

Judgment once formed was rarely dislodgeable. It is amusing to see the efforts of Reagan’s ghostwriter in this book to make him change or correct his tales, with only partial success. Reagan used to attribute a quote to “Nikolai Lenin” which he actually drew from one of Robert Welch’s publications for the John Birch society. Robert Lindsey obviously could not make him stop using the spurious quote (it shows up first on page 239 and then again, verbatim. on page 474), but at least Lindsey slips in a prefatory “I had been told that Lenin once said…” in each place. Stories Reagan wrote in his earlier autobiography, Where’s the Rest of Me?, are brought a bit closer to the truth without ever making it all the way. He no longer says that Lowell Park, where he worked as lifeguard, was the place where James Russell Lowell wrote “To a Waterfowl”—William Cullen Bryant’s indignant spirit need no longer be vexed on that point. But Reagan continues to think the park was named for the poet Lowell, though there is evidence that Lindsey knows my book on Reagan, which quotes the dedication plaque in the park.*

The same process of partial correction takes place in Reagan’s account of his “student strike” at Eureka College, his war with Communists in Hollywood, and his troubled relations with GE. Discrepancies between the book and Where’s the Rest of Me? are quietly ignored—there is no reference to the earlier book, whose fantasies are supposed to be superseded by this one. The obstinacy of Reagan in clinging to at least a part of each old familiar story shows how unwilling he is to be disoriented in the plot line he has chosen for his life.

At only one point in this book does Reagan come close to reflecting on his own character. In 1985, by inspecting the school records in all the towns where Reagan spent his childhood, I established something Reagan had not alluded to in his interviews or reminiscences—that he was in four different schools in four different towns between the ages of six and ten. That is one of several things picked up by Lindsey and added to the Reagan story. Then Reagan himself (presumably) reacts to this datum:

I’m sure that the fact our family moved so often left a mark on me. Although I always had lots of playmates, during those first years in Dixon I was a little introverted and probably a little slow in making really close friends. In some ways I think this reluctance to get close to people never left me completely. I’ve never had trouble making friends, but I’ve been inclined to hold back a little of myself, reserving it for myself.

This acute remark of Reagan’s (if it is Reagan’s) corresponds to the impression received by those who served with him in campaigns, at the governor’s mansion, and in the White House—that the man, so warm and congenial before crowds, is oddly remote in private. He was early given an “official friend” in Washington—Senator Paul Laxalt—to show that he was not a total stranger to the capital. But all his friends seem to be official friends, with the exception of Nancy, who is the conduit when not the container of all his personal relations. Reagan was left, after a long engagement, by the first woman he proposed to (Margaret Cleaver) and by his first wife (Jane Wyman), and he admitted to fan-magazine interviewers that he was cautious about risking another disappointment in love. The totality of his embrace of and by Nancy seems to have relieved him of the need for other intimacies (even with his own children).

Advertisement

Reagan also admits that his childhood failure as an athlete troubled him deeply until he learned its cause—his extreme shortsightedness. Today it would be almost impossible for a boy to reach the age of twelve without parents or teachers noticing that he could not see much beyond a small cleared circle; yet Reagan tells us it came as a revelation when he looked through his mother’s glasses and realized the world was not one large fuzzy setting for a few foreground details. The cautious way Reagan carries himself in his action movies shows that the effect of those formative blind years stayed with him. Too vain to wear glasses in public, Reagan also forwent contact lenses when acting, since the early lenses magnified his pupils. When he played the hero with piercing eyes, he was gazing out on a blur. He tells us he started going deaf from a gunshot near his ear during the late 1930s, when he was still in his twenties, so his audible as well as his visual orientation to the world around him was attenuated.

Many performers, used to life in the isolating cone of a spotlight’s dazzle, seem to end up listening to themselves. Caught up in the heightened reality of make-believe, they find the everyday world dim and uninteresting. Reagan was isolated even within that reality capsule, cut off from the other actors unless they swam close up to his eyes and ears. Like many people of impaired vision or hearing (and he had both), he learned to disguise his difficulty in a pretense that he had seen and heard everything instead of disjunct bits of episodes or conversations. An air of serenity, a slight distance from one’s surroundings, serves as a protection for the gaps in perception. Things had to be “placed,” put in their proper niche, if he was to maneuver through terrain too unfamiliar when it lacked identifying labels.

Signaling good intentions out from his highly visible bubble, stranded while he enacts “communication,” Reagan creates the reality he is voicing, Magoolike, no matter what untoward events are occurring all around him. That is the story of lran-contra. He knew what he wanted to do, and that, he is convinced, is what was going on until Colonel North exceeded instructions. In the same way, he is convinced that his businessmen brought on prosperity, a restoration of trust in government, and an end of the cold war. These are nice things to believe, and he will continue believing them. Happy and loved in his traveling little cone of light, he left behind a country more cynical about politics than at any time in recent memory, a scandalous S & L mess we shall be paying for into the next century, a national debt that cripples our ability to help others or ourselves. But Mr. Magoo never has to see the devastation he leaves in his wake.

This Issue

December 20, 1990

-

*

Garry Wills, Reagan’s America: Innocents at Home (Doubleday, 1987), p. 30: “A plaque put up by donors on the beach says it [the Park] is dedicated to ‘Charles Russell Lowell, Colonel of Second Massachusetts Cavalry, Brigadier General United States Volunteers, killed at Cedar Creek, Virginia. October 19, 1864’.” ↩