A third of all marriages in England and half of all those in the United States, according to recent estimates, will end in the divorce court. We are still saddened, sometimes even shocked, when a friend’s marriage breaks up, but divorce is no longer a matter for scandalized concern. We have come to accept it as a normal feature of life, though opinions differ over whether it should be bracketed with cancer and AIDS as a curse of our times or celebrated along with aspirin and anesthetics as a welcome liberation from past miseries.

The contemporary notion of marriage as a legal contract from which either partner can walk away when so inclined is extremely recent. In medieval Europe the Church maintained the absolute indissolubility of a valid marriage. In certain circumstances the ecclesiastical courts could order a separation from board and bed (a mensa et thoro), but neither spouse was allowed to remarry during the other’s lifetime. With the Reformation, when marriage ceased to be a sacrament, most Protestant countries allowed divorce with remarriage in cases of adultery or other serious marital fault. But in England Puritan pressure to introduce divorce was unsuccessful and the law remained unchanged until 1857. In all countries the divorce rate was infinitesimal. The great revolution came only in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the concept of no-fault divorce swept through the Western world. Although the notion of marital fault still lingers, the most common position nowadays is that a marriage may be dissolved when a court is persuaded that it has irretrievably broken down. The accompaniment to this legal change has been a soaring divorce rate. In England and Wales it has increased sixfold since 1960.

Lawrence Stone is therefore fully entitled to describe “the metamorphosis of a largely non-separating and non-divorcing society, such as England from the Middle Ages to the mid-nineteenth century, into a separating and divorcing one in the late twentieth” as “perhaps the most profound and far-reaching social change to have occurred in the last five hundred years.” As such, it is a suitable subject to engage a historian who has never shirked large themes. During the past thirty-five years Lawrence Stone has published seven substantial books founded upon primary research, along with numerous articles and papers. His characteristic method is to pick a huge subject, ransack scores of libraries, tramp around the record offices of England, accumulate mountains of microfilm and xeroxes, enlist the aid of his wife, Jeanne Fawtier Stone, and then sit down to write a large book, stuffed with figures and tables but expressed in colorful and trenchant prose. If, after all this, some severe critics can detect an unduly schematic approach, occasional errors of fact, some internal inconsistencies, and a penchant for hyperbole, who can complain? More cautious scholars could not have attempted a fraction of this work in a lifetime. Stone has that “audacity” without which, as F.W. Maitland once remarked, people never get things done. His energy and his achievement are stupendous.

In tackling the subject of divorce, Stone is, so to speak, not entering virgin territory. The outlines of the English law of marriage and divorce were established long ago in such admirable pioneering works as G.E. Howard’s A History of Matrimonial Institutions (1904) and L.T. Dibdin and C.E.H. Chadwyck Healey’s English Church Law and Divorce (1912). More recently, Roderick Phillips’s Putting Asunder: A History of Divorce in Western Society (1988), which unfortunately came too late for Stone to take into account in his book, but which he has subsequently discussed in The New York Review,1 provides an excellent overall view of the subject; its bibliography lists scores of monographs on divorce in every country from Norway to Canada. Stone’s book therefore contains fewer surprises than some of his earlier works. But it breathes new life into an old subject by advancing fresh hypotheses and much fascinating new material.

Stone sets himself two main tasks. The first is to analyze the evolution of the English law of marriage and divorce since the sixteenth century. The second is to trace changing moral values in England concerning the relationships betwen the sexes, a process which he categorizes as the shift from patriarchy to sexual equality. His book covers the last four hundred years, but it concentrates on the period between 1660 and 1857 and draws heavily on the records of the Court of Arches, the ecclesiastical appeal court for the Province of Canterbury (i.e., Midland and southern England). The full results of Stone’s labors on these records will appear within the next two years in two ancillary volumes of case studies, one on marriage before 1753 (Uncertain Unions) and one on divorce before 1857 (Broken Lives). These volumes are frequently cited in the notes to the present book and their present unavailability is tantalizing. When Stone tells us enigmatically that for “the story of the Harris girls” we must wait for Uncertain Unions, he reminds us of Dr. Watson alluding to one of Sherlock Holmes’s unpublished casebooks.

Advertisement

Dr. Watson, however, was at pains to reassure his readers that

the writers of agonized letters, who beg that the honour of their families or the reputation of famous forbears may not be touched, have nothing to fear. The discretion and high sense of professional honour which have always distinguished my friend are still at work in the choice of these memoirs, and no confidence will be abused.

(“The Veiled Lodger”)

Lawrence Stone, alas, has no desire to preserve any reputations. He promises that the records of matrimonial litigation will “allow us to peer closer into the human condition in the past than any other records which have survived”; and he warns that

the readers of this material do indeed become historical voyeurs, peering through keyholes, cracks in deal partitions, or holes deliberately drilled for the purpose, or listening with ears against the wall. What they hear are conversations around the fire in the kitchen, soft cries and whispers, the normal hubbub of life in a household; occasionally also the screams of battered wives or the sounds of adulterous intercourse.

This enticing prospect sustains the reader through a book which is, however, largely devoted to the intricacies of legal history.

Stone’s opening theme is the extreme informality of marital unions in early modern England. He points out that although it was usual for a couple to marry at a public ceremony in church conducted by a clergyman after the banns had been called, there was no strict need for this. In canon law a verbal contract without any church ceremony was sufficient. A contract de presenti, that is in the present tense, was binding forthwith; a contract de futuro, that is a promise for the future, only constituted a marriage if followed by sexual consummation. The common law refused to confer property rights arising from marriage upon those who had not been married publicly in church. But in the lower reaches of the social scale, where property was not an issue, matrimony by private contract was common. Once a child had been conceived, the couple lived together and saw themselves as “married in the eyes of God.”

The ability of boys over fourteen and girls over twelve to get privately married was a source of anxiety to parents and led to innumerable legal disputes. Many girls were lured into sexual relations by private “contracts” and then abandoned. “Privy contracts” were frequently invoked in attempts to dissolve later relationships. Stone concludes baldly that there was no consensus on how a legally binding marriage should be carried out and that the law was “a mess.”

Until 1753, moreover, it was possible for a runaway pair to make a clandestine marriage by invoking the aid of some unscrupulous cleric who would marry the couple without bothering with banns or the consent of parents. Already common in the early seventeenth century, this practice multiplied in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, when as many as 15 to 20 percent of all marriages may have been made in this way. Only after Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 did banns, witnesses, and a church ceremony in the locality become essential for a valid marriage. Even then it was still possible to hire a chaise and elope to Gretna Green, where the Scottish law made it possible to marry without any tiresome formalities. Among the poor, sexual relations before marriage became increasingly common. By the early nineteenth century a third of all brides were pregnant at the time of their wedding.

The widespread cohabitation of unmarried couples is normally regarded as a feature of very recent times. The latest General Household Survey of Britain reveals that the proportion of couples in England who have lived together before marriage has risen from 6 percent in the late 1960s to 27 percent; and in the Southeast, 21 percent of all cohabiting couples are unmarried. As Stone declares, the Western world has become full of couples “in various stages of negotiation”; there is, he says, no longer any “single socially accepted mode of formal bonding.” What his book makes clear, however, is that this state of affairs is in many ways a return to conditions obtaining in early modern England.

The uncertainty of the marriage law meant that de facto divorce and remarriage did in practice take place. Unions formed by “privy contracts” were often set aside in favour of a marriage made with someone else in church. Poor law records reveal a high proportion of wives whose husbands had deserted them; and early modern England must have swarmed with lower-class bigamists. By the eighteenth century, the poor had developed their own system of self-divorce—the ritual wife-sale, in which the wife was put up for auction in a market with a halter round her neck like a cow, and sold to another man, normally the lover she had already taken. Stone rightly suggests that the frequency of this practice has been exaggerated. But desertion and what would later be called “common-law marriage” were undoubtedly wide-spread. A recent study of settlement examinations in eighteenth-century Devon shows that “what constituted a marriage in law was often confused and a variety of relationships were popularly thought to be acceptable.”2

Advertisement

For couples who felt they had to observe the law, the options for dissolving marriage were fewer. The church courts offered a judicial separation to those who could prove a spouse’s adultery, desertion, or cruelty. In the immediate wake of the Reformation some couples took this as a licence to remarry, but the Church of England soon removed any ambiguity on this point. Thereafter most couples separated without the expense and publicity of litigation. Those who went to the courts usually did so in order to wrangle about alimony.

Without a judicial decree, it was possible to separate more or less amicably by a formal deed in which the husband made a financial allowance to his wife in return for an indemnity against the debts she might incur. This gave the wife economic freedom and some legal independence, though the shaky legal status of these separation deeds could make them difficult to enforce. Stone regards such private separations as “a form of quasi-legal collusive self-divorce, which in practice opened the way to the formation of a new adulterous or bigamous household.” They performed the same function for the middle classes as did public wife-sales for the poor.

More dramatic, and certainly more enjoyable for the onlookers, was the right of the husband to sue his wife’s lover in the common law courts for “criminal conversation.” This was an extension of the action for trespass and huge costs could be awarded, with prison as a punishment for those who could not pay. In the 1790s Lord Kenyon, the Lord Chief Justice, and Thomas Erskine, the fashionable counsel for the plaintiff, conducted a virtual reign of terror against the male seducers of the day by histrionically denouncing their immoralities and calling for punitive damages. These cases of criminal conversation were avidly reported and published as salacious reading for the eighteenth-century public. (Lawrence Stone’s forthcoming volumes of case studies will make a distinguished addition to this genre.)

Stone comments that the popularity of this form of litigation shows that aristocrats now preferred monetary damages to the satisfaction afforded by challenging their rivals to a duel. He might have added that it also reveals the eighteenth century’s wholly different attitude to what the Elizabethans would have called cuckoldry. A century earlier it would have been impossibly humiliating for a husband to adduce evidence in a public court of the precise circumstances in which his wife had betrayed him. Stone gives an enthralling account of the role of servants as witnesses in such cases. If a mistress was entertaining a lover in her husband’s absence, it was usually the servants who were decisive in bringing the matter to a head; and loyal servants were thrown into moral confusion by the dilemma of whether to be faithful to their mistress or to inform their master. It is interesting to speculate on the extent to which adultery by well-to-do women in modern times has increased because they no longer have waiting women to attend their every movement.

Neither monetary damages nor formal separations enabled the parties to remarry. For that, the only mechanism was divorce by act of Parliament. This procedure was anticipated in 1670 by Lord Roos, who secured an act enabling him to marry after a judicial separation from his promiscuous wife and a lurid hearing in the House of Lords, attended incognito by Charles II, who found it “better than a play.” Parliamentary divorce got under way in the 1690s. It was exceedingly expensive and there were only a little over three hundred cases before 1857, when the procedure was ended.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, therefore, England saw very few legal divorces, but a great deal of misery, infidelity, desertion, and concubinage. In 1857 the law was at last reformed and a new secular court established to award divorce with the right to remarry in cases of adultery by the wife or adultery aggravated by cruelty or desertion by the husband. But the new act did not make England a divorcing society. As late as 1914 there were fewer than a thousand divorces a year in a population of forty million. The divorce law was extended further in 1923 and again in 1937. But it was Leo Abse’s no-fault act of 1969 which released the floodgates.

Stone is scathing about the legal complexities of the unreformed system. “To enter the eighteenth-century machinery of law,” he says, “is to penetrate the heart of darkness.” Matrimonial law was hopelessly complicated by the existence of competing systems of jurisdiction. The canon law determined the rules of marriage; the common law decided questions of property; equity dealt with trusts and alimony. The result was confusion. The status of a private separation deed, for example, was said in 1827 to be that

a court of equity will not enforce it;…a court of [common] law will not entertain an action founded on the breach of it, though the very same court would enforce the due observance of it; and…the spiritual court may pronounce a sentence for the restitution of those very rights which the legal tribunal had declared the husband to have renounced beyond the power of revocation.

Fortunately, Stone spares the reader some of these complications. His interest lies in the human drama and its social meaning. He enjoys the scabrous, Hogarthian side of eighteenth-century life; and some of the contemporary plates that illustrate his book leave nothing to the imagination. His text abounds in graphic vignettes of adultery and the places in which it was committed: “The undulating motion of the coach, with the pretty little occasional jolts, contribute greatly to enhance the pleasure of the critical moment, if all matters are rightly placed,” as one eighteenth-century magazine put it. Stone gives a hilarious account of the downfall of Thomas, Lord Erskine, one-time scourge of adulterers. Threatened in 1820 with a breach-of-promise suit by a girl to whom he had written love letters, he decided to run off to Gretna Green with his housekeeper and long-time mistress. To throw the girl off the scent, he traveled to Scotland ” ‘disguised in female clothes with a large Leghorn bonnet and veil.’ ” This spectacle, anticipatory of Mr. Toad’s escape from jail disguised as a washer-woman, was immortalized in a contemporary cartoon which Stone reproduces.

Three recurring themes run through Stone’s account. The first is the way in which the ruling elite’s concern to secure their property overrode all other considerations. The purpose of Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 outlawing clandestine unions was to safeguard the property of rich families from penniless adventurers who tried to elope with their sons and daughters. The justification for the criminal conversation cases was that the wife’s adultery was conceived of as the “highest invasion of property.” The reason for the introduction of divorce by act of Parliament was that some members of the wealthy elite wanted to divorce their adulterous or childless wives in order to be able to remarry and produce legitimate offspring to inherit their estates.

The second and closely associated theme is the continuing reluctance of legislators to make divorce possible for the poor. The only legal way out of an unhappy marriage was formidably expensive. In a famous ironic judgment in a bigamy case of 1845, Mr. Justice Maule reproached the defendant, a poor working man, for failing to sue his wife’s seducer and then petition the House of Lords for a divorce: “It would cost you perhaps five or six hundred pounds, and you do not seem to be worth as many pence. But it is the boast of the law that it is impartial, and makes no difference between the rich and the poor…. You have thus wilfully rejected the boon the legislature offered you.” In the debates preceding the act of 1857, Lord Redesdale said that it would be “a dangerous step to throw open the power of divorce to the whole society,” while Bishop Wilberforce opined that “equal justice to the poor would be purchased at the price of the introduction of unlimited pollution.” Not until the introduction of extensive legal aid, by a Labour government in 1948, was divorce really open to the poor. Today the divorce rate of manual workers is three times that of professional couples.

Stone’s third theme is the plight of women during these centuries and the slow evolution of opinion about the nature of the marriage relationship. “Men make the laws and women are the victims,” said Lord Lyndhurst in the 1850s. Until the later nineteenth century a married woman lacked an independent legal identity. She was excluded from testifying in cases of criminal conversation. For most of the period she was not allowed to initiate a divorce by act of Parliament. If abandoned by her husband, she had no right to keep her separate earnings. Even her children were the property of her husband, who could deny her access to them. The double standard of sexual morality meant that not until 1923 was a women entitled to seek a divorce on the grounds of her husband’s adultery alone; yet a single lapse on her part would stop her maintenance allowance.

Stone traces the reforms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries which gradually brought the law nearer to sexual equality. He shows how the definition of “cruelty” by the husband moved from a strictly physical one to embrace the concept of “coldness and neglect”; and he charts the changes in the law of custody which gave women equal rights to access to their children. He explains why, in the absence of contraception and genetic coding, even a single act of adultery by the wife was an unpardonable breach of the law of property and the idea of hereditary descent, since “it presented a threat to the orderly transmission of property and status by the possible introduction of spurious offspring.” Above all, he chronicles the shift to the view of marriage as an emotional relationship rather than a partnership of convenience.

Yet today, when over 70 percent of the petitioners for divorce are women, it is still they who are the sufferers. Divorced women are less likely to remarry than are men and a large proportion of them, especially those with young children, face severe financial problems. Until it is clear how women who have made sacrifices (for example, by neglecting their own professional careers) can be adequately compensated for the breakup of their marriages, it cannot be said that the financial implications of no-fault divorce have yet been worked out.3

Whether the easy divorce of the late twentieth century has led to an increase in human happiness seems anyone’s guess. Much depends upon how one interprets its high frequency. One approach is to say that the change is merely a legal one: marriages broke down just as often in the past, but it is only nowadays that these failed unions can be dissolved. The Royal Commission on Divorce of 1956 accordingly urged that a high divorce rate was a sign of health: it permitted the burial of “dead” marriages in order to create “live” ones. Stone’s own view is that until the middle of the twentieth century all that had happened was that the availability of legal aid had made it easier to dissolve marriages which had already failed.

But the alternative view is that in the modern world the rate of marriage breakdown has greatly increased. This is the case put forward by Roderick Phillips in Putting Asunder. He argues that in the past the traditional family economy and the lack of workable alternatives to marriage resulted in marital stability. That stability derived not from the strength of emotional ties between the partners but from their unified economic base. Today, however, the old family economy has dissolved. Husband and wife are independent earners and it is possible for single people to live alone. Divorce is thus a practical possibility in the way it never was.

Marriage breakdown has also been facilitated by the decline of familial and neighborly surveillance. Stone illuminates the origins of the new concept of private life by tracing the increasing preference of the early-modern upper classes for marriages by special license, away from the vulgar publicity of banns and onlookers. What he calls “the dogged desire for privacy” led to private separation deeds in place of court hearings. In 1749 one contemporary deplored the “officious or impertinent enquiring and canvassing private affairs by a public court of justice”; the relationship between a man and his wife was no one else’s business.4 Today it is even regarded as an impertinence to inquire of an acquaintance whether he or she is married. The social pressures that in the past kept husbands and wives together have largely dissolved.

Meanwhile emotional expectations by married couples have risen to what Stone describes as “quite unrealistic levels.” The growth of romantic love, a consumerist ideology, sexual hedonism, and the freedom to choose one’s own partner, unhampered by intervention from family or friends, have paradoxically made marital unions less stable. Stone points to the supreme irony that couples who live together experimentally before marriage are more likely to get divorced than those who do not.

It seems, therefore, that the more marriage is prized for the sexual or emotional gratification it affords, the less durable is it likely to be. Samuel Eliot Morison once wrote that “it was easier to obtain a divorce in New England in the seventeenth century than in old England; for the Puritans, having laid such store on wedded love, wished every marriage to be a success.”5 The radical sectaries of the early modern period, who were said to favor divorce for “misliking,” and the reformers like John Milton or his eighteenth-century follower Peter Annet (not mentioned by Stone), who wanted to dissolve any marriage which did not bring happiness to the partners, were thus preparing the way for our modern condition.

Stone castigates “the idealization of the individual pursuit of gratification and personal pleasure at the expense of a sense of reciprocal obligations and duties towards helpless dependants, such as children.” He concedes that it is unclear whether “the sudden deprivation of a father, the sale of the family home, and possible lapse into unaccustomed poverty in a single-parent household are or are not more damaging to a child than growing up with bitterly quarrelling or negligent parents.” He also points that in the past the death of a parent was as frequent a cause of childhood deprivation as is divorce today; the rise in the divorce rate can even be seen as “a compensatory mechanism for the decline in adult morality, and the consequent prolongation of the duration of marriage.” Yet many schoolteachers would say from observation that the psychological effects of divorce upon a child are often as traumatic as those of parental death; and it is well known that the children of divorced parents are themselves more likely to divorce when they grow up. Divorce may be a functional substitute for premature parental death, but its consequences can be longer lasting.

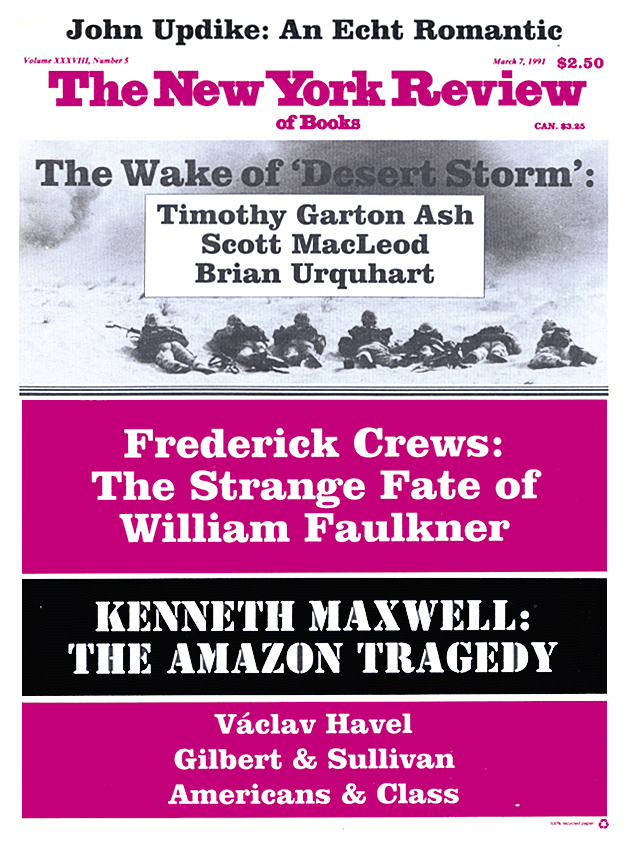

This Issue

March 7, 1991

-

1

March 2, 1989. ↩

-

2

Pamela Sharpe, “Marital Separation in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries,” Local Population Studies, 45 (Autumn 1990), pp. 68–69. ↩

-

3

This is the theme of a recent volume of essays on current problems of American divorce law in Divorce Reform at the Crossroads, edited by Stephen D. Sugarman and Herma Hill Kay (Yale University Press, 1990). ↩

-

4

See Peter Annet, Social Bliss Considered (London, 1749). ↩

-

5

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Intellectual Life of Colonial New England (2nd edition, Cornell University Press, 1960), p. 10. ↩