In the circumstances created by the war in the Gulf, it is not enough to concentrate only on postwar security arrangements and the control of arms sales to Iraq, as desirable as these goals are. For unless the victors in the Gulf War pursue some kind of constructive vision regarding the political future of Iraq, Kuwaiti sovereignty may very well have been restored at the cost of Iraqi sovereignty and still more loss of life.

A gradual slide into anarchy, civil war, and possible defacto fragmentation is already being threatened by the revolts in Basra, Nasiriya, Erbil, and other southern and northern cities. The suppression of these uprisings by Saddam Hussein’s regime is going to be a very bloody business indeed. The bloodletting now going on in Iraq is still in its infancy. Mustard gas may already have been used in Basra, according to the London Daily Telegraph of March 7. The wild Baathi rhetoric about security forces creating “rivers of blood” may well become a reality. But the principal victims, as always, will be the long-suffering people of Iraq.

For the Iraqi people, the cost of enforcing the will of the United Nations has been grotesque. We shall never know exactly how many Iraqis died. Speaking of what the Allied forces found in the bunkers and trenches along the Saudi-Kuwaiti border, General Schwarzkopf was refreshingly frank: “There were a very, very large number of dead in these units, a very, very large number indeed.”1 The estimate of the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Les Aspin, that at least 65,000 Iraqi soldiers were killed2 is supported by Israeli sources who speak of one to two hundred thousand Iraqi casualties. Most of the killing, moreover, took place during the ground war. Fleeing soldiers were bombed with a neat device known as a “fuel-air explosive,” which creates a fireball effect that incinerates or asphyxiates everything around it. As Michael Kinsley reported in The New Republic,3 during the period before the war broke out this was called the “poor man’s nuclear weapon,” and its horrific effects were described at length. But as things turned out Iraq was unable to make effective use of the weapon; only the United States did so.

Did so many Iraqis who did not want to fight have to die? And did an entire country have to be left “brain-dead,” as Richard Reid of the United Nations Children’s Fund described it following a mission to survey damage to the city’s water supply? Baghdad, he said, where some four million people live, is a city “essentially unmarked, a body with its skin basically intact, with every main bone broken and with its joints and tendons cut…. The health system is collapsing. There are no phones and no electricity and no petrol and only a people reduced to daily improvisations and scroungings.”4 Why was Baghdad being bombed so intensively while the Iraqi army was in full rout? Iraqis like myself who opposed the Baathist regime for years and welcomed the formation of a coalition against it have to ask: Does an entire country have to be crippled to enforce a principle?

There are two moral questions here: the wanton quality of the violence over and above what was required to dislodge the Iraqi army from Kuwait; and second, the disproportion between the amount of violence used and the values supposedly being upheld. Whatever the answers may be—and it is up to Americans to come up with them—such violence as was inflicted upon Iraq carries with it a responsibility toward those who have been its victims.

The bombing of Dresden and the use of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not by themselves change the course of German and Japanese politics. It took a commitment by the allies to the future of Germany and Japan to do that. The contrast with the humiliations of the settlement following World War I could not have been more striking. So far as precedents for the present situation are concerned, we have little more to go on than these two models from the past, with all that they imply. Which one will the victors in the Gulf War choose? The early signs are not good. It is true that on March 13 (as this issue of The New York Review went to press) the Bush administration warned Iraq not to use helicopter gunships against the insurrections. But for the most part the Bush administration is turning a blind eye to the members of the Iraqi opposition on the grounds that any kind of support for them would be tantamount to interference in the internal affairs of another country. This is a mockery of language, of thought, and of the common sense of Americans.

The terrible facts of this war could make for a pyrrhic victory indeed, one likely to be accompanied in the long run by structural instability throughout the countries known as the fertile crescent. In the weeks, months, and years to come, the bloodletting by the Baath regime may yet combine with the scale of the destruction wreaked by the Gulf War, to result in a human catastrophe of genocidal proportions. Add to this the likelihood that little or no progress will be made on the Palestinian question, and you have a volatile combination of ingredients that can reinforce the worst kind of politics in the region, a politics that feeds on despair, hopelessness, and millenarian solutions to appalling problems. The long-term consequences of leaving a broken Iraq to fester and die are too awful to contemplate.

Advertisement

At the same time, paradoxically, the very scale of the Iraqi defeat brings with it a great opportunity. The opportunity is to establish in Iraq a demilitarized, genuinely secular, federated republic founded on working democratic institutions. This opportunity, however, is only possible if the victors in the recent war work with the members of the Iraqi opposition on a lasting basis and with such a vision in mind. The Iraqi opposition groups are unable to achieve this vision by themselves. They need help. The only credible source for that help is, ironically, the powers that have crippled their country and, until now, have left it to rot and die, still under the rule of the Baath. The legacy of hate and bitterness toward the West is already mounting in Iraq. The only way for Americans to staunch the terrible wounds of war is for them to reach out to Iraqis who want a different government and make it clear that what happens in Iraq now seriously matters to them.

The US and its allies should be actively helping and entering into negotiations with members of the Iraqi opposition. In their public statements and actions they should distinguish between the people of Iraq and the illegitimate government apparatus that is waging war on its own population. They should insist that Iraqis fleeing possible persecution should be allowed to cross into Kuwait. They should put Saddam Hussein’s government on notice more strongly than they have so far that its acts of repression are being observed and could be subject to a military response. They should make it clear that help with reconstruction will be forthcoming if a new, democratic regime replaces that of Saddam Hussein.

They should also consider deploying a temporary army of occupation to keep the peace and restore basic services pending the formation of a transitional Iraqi government and the organization of a new Iraqi internal security force drawn from the existing units of the army. Such an army of occupation should not leave Iraq until an overall settlement regarding postwar security arrangements for the region has been arrived at, including guarantees of the territorial integrity of Iraq.

What kind of new regime might emerge? If I say that a secular, demilitarized, and federated republic in Iraq is now feasible, I expect people in the US and Europe to be instantly and deeply skeptical. With good reason. Please remember, however, that if before August 2, 1990, I had said that Baathi Iraq represented a grave threat to the security of the entire region, many politically sophisticated Americans would have been just as skeptical. Iraq is a country of great imaginative extremes. Often hidden in the folds of one wild extreme is the possibility of another.

Both the dangers and the opportunities arise from the same source. They arise from the very specific nature of the polity built up during the last twenty-two years. They arise from the deformed yet still quintessentially modern experience that the Baathist experiment imposed on Iraq. The key factor that remains little understood is the nature of the society that has existed in Iraq, a society that has now been shaken to its very foundations by two things: first, the sheer scale of the devastation and destruction inflicted on Iraq by American firepower; and, second, the magnitude of the allied victory brought about by the destruction. The grounds for both despair and hope are to be found in these momentous facts. In my view the outcome in the weeks and months ahead will depend almost entirely on the policies followed by the victors in this war. For even if the insurrections that have been taking place in Basra, Erbil, and other cities were able to achieve their goal of toppling the regime, they would by themselves be incapable of reversing the trend toward the disintegration of Iraq. On the contrary, the insurrections going on today, with which of course I strongly sympathize, are themselves confirmation of the disintegration that now afflicts Iraq.

I will try to show here why the opportunity to create a new republic is based on Iraqi realities, not on fantasy, and to argue that Iraqis have no alternative to adopting such a program. Or to put it differently, the only alternative that the Iraqis have to adopting such a goal—and, in spite of everything, asking the help of the victors in the recent war in order to achieve it—is collective suicide.

Advertisement

In 1933, on the eve of his death, Iraq’s first and wisest ruler of modern times, King Faisal I, wrote the following words in a confidential memorandum:

There is still—and I say this with sorrow—no Iraqi people but unimaginable masses of human beings, devoid of any patriotic idea, imbued with religious traditions and absurdities, connected by no common tie, giving ear to evil, prone to anarchy, and perpetually ready to rise against any government whatever. Out of these masses we want to fashion a people which we would train, educate, and refine…. The circumstances being what they are, the immenseness of the efforts needed for this can be imagined.5

King Faisal and Saddam Hussein, the first and the last rulers of modern Iraq, are the antipodes of Iraqi politics. One could not imagine a more striking contrast in personality and style of government. The cruelty and megalomania of Saddam Hussein’s political temperament have already entered the canons of folklore. Faisal by contrast was wise, tolerant, worldly, a patient negotiator who was prepared to cajole, admonish, tease, and even to deceive his subjects into becoming modern citizens. In short he was prepared to do virtually anything in the effort to encourage them to change themselves and then society, except to use force.

King Faisal died a broken man. He spent the last months of his life trying to stave off a pogrom that was about to be conducted against the Assyrian community in Iraq. He failed to do so.

But Faisal died almost sixty years ago. Iraq today is a completely different kind of place from the land he ruled. The population has grown from 3.3 million people to 17 million people, most of whom live in cities, follow modern ways, and have never known anything other than an urban way of life. The literacy rate in Iraq today is one of the highest in the third world; its citizens are not the disease-ridden, poverty-stricken tribesmen and peasant-serfs of the Faisal years. Ten years ago, before the social impact of the Iraq-Iran War, women accounted for 46 percent of all teachers, 29 percent of all doctors, 46 percent of all dentists, and 70 percent of all pharmacists in the country. During the recent war women largely made up the staffs of all the ministries and ran much of the civilian life of the country.

Most of these changes were achieved under the Baath. One must give the devil his due. The Baath made a radical break with Iraqi backwardness and should not be seen simply as a continuation of it. Iraq under the Baath overcame much of what Faisal during his thirteen years as king had so clearly failed to overcome. But the Baath leaders achieved all this in ways that Faisal would never have dreamed of. They injected previously unimaginable kinds and degrees of violence into the daily lives of Iraqis. You might say that, by using the windfall opportunity provided by oil revenues, they forced people to live more modern and more prosperous lives.

The Iraqi Baath not only built up the fifth largest army in the world and an enormous, pervasive secret police; it also transformed Iraq’s physical infrastructure, its educational system, social relations, and its technology, industry, and science. The Baath regime provided free health and education for everyone, and it also revolutionized transport and electrified virtually every village in the country. Iraq has today a proportionately very large middle class; its intelligentsia is one of the best educated in the Arab world. How else could the country have become such a threat to the region?

In King Faisal’s time a peasant had his tribe, his religion, his sect, his village, and his allegiance to the sheik whose lands he tilled. His entire world was constructed from these elements. The Baath leaders like to talk of themselves as having created a “new society” and a “new Arab individual.” Whenever I hear the phrase “a new world order” I get the shivers because it reminds me of such Baathist language. But the important point is to admit that to a large extent the Baathist rulers succeeded—or at least they succeeded in some very important respects.

This is certainly not to say that extreme terror and violence were necessary for Iraq’s development. That would be absurd. There are many different, and possibly shorter, routes for climbing the ladder of development. The true hero of Iraq’s story is Faisal, not Saddam. The reality is that Saddam did much of what Faisal failed to do, but the central problem facing Iraq at this critical moment in its history is how to discard the politics of Saddam Hussein and reinvent, in a new and discernibly modern form, the tolerant ways of Faisal.

Iraq is today a modern mass society of consumers whose dominating idea, up to the Gulf War, was that each person’s status was defined by the same standard: that is, by his or her relation to the party-state and its leader. Circumstances of birth, territoriality, religion, education, and even class by and large no longer determined privilege or status in Baath Iraq. In the past these various circumstances had given rise to a multitude of ethnic, religious, and political allegiances, the same allegiances that had so troubled King Faisal when he generously tried to accommodate them all within the shell of a modern nation-state. By contrast the deepest and most distinctive characteristic of Baathism is that, unlike Faisal, it cannot tolerate diversity in allegiance or “difference” in anything.

The old world of Faisal and its rules are now gone in Iraq. What held the new world of Saddam together? People were ripped out of a traditional system of social and personal relations; their lives became fragmented and atomized in an emphatically modern way, while at the same time they were strictly forbidden to read anything that was not approved by a censor. The ideal Baathist citizen is never an individual; he or she is always a faceless member of a mass. Iraqis have not been in a position to think a new political thought for twenty years. But at the same time they have changed out of all recognition from what they were before.

Civil society, in the sense of voluntary associations separate from the state, did not replace traditional society in Iraq. Character and personality shriveled up. Here lies the great danger for the future. Because of the pervasive activities of informer networks and the secret police, fear, suspicion, distrust, and complicity entered into people’s relations with one another. These became the terrible bonds of citizenship in Iraq.

The problem is not that Iraq is such a strange place, or that it is more pervaded by violence than other dictatorships have been, but that the violence is still too raw and close to the surface for an organized opposition or even for “samizdat” literature to have emerged as it did in Eastern Europe. Unlike even the Ceausescu regime, Saddam Hussein’s regime had not yet become rotten from the inside before the invasion of August 2, 1990, came along to change everything.

In such Kafkaesque conditions, how can secularism be justified, not as a desirable end in itself, but as a practical and workable way out of the mess in which the victors of this war have left Iraq? To answer this question we need to consider what happened to the traditionally divided forces that used to dominate King Faisal’s world. Consider first that great hidden divide of Iraqi politics between Suniism and Shi’ism.

Historically the Shi’ite Arabs have been widely discriminated against in Iraq, both socially and politically, although they make up a majority of Iraqi citizens. Two contradictory things happened to the division between Sunni and Shi’a as a result of the modernization conducted by the Baath. The first is suggested by the great collective experience of the Iran-Iraq War, which confirmed that the breakup of traditional religious-communal bonds had gone very far indeed. Shi’ite soldiers led largely (although not exclusively) by Sunni officers fought the army of the Islamic republic of Iran for eight years. No doubt they were unwilling soldiers; but in that they were no different from their civilian counterparts who did not choose the Baath party yet who, through violence and fear, became, in spite of themselves, complicit in its twenty-year dictatorship. Fear is not a very effective force for impelling an army to fight, as the Allied forces in the Gulf War also found out. Nonetheless, after a fashion, it works. The experience of the Iraq-Iran War shows that much, at least.

The second thing that happened, however, is probably the most tragic and paradoxical of all. The modernization of society under Baathi rule simultaneously intensified sectarianism at the same time as the Baathi leaders tried to erase the Shi’ite identity of the majority of Iraqis. A new kind of sectarianism started to grow from the bottom up, so to speak. It differs from the old in that it starts from the lack of trust that has been created between people, not the unself-conscious ties of community that have been implied for many centuries in the Middle East just by being in a place such as Iraq and by being a Shi’ite or being a Sunni. You could not trust anyone under Saddam’s regime, but at least you would distrust the members of your own family and sect less than others. Mixed marriages decreased; sectarian jokes became more common. Sectarianism now was a way of providing frightened and atomized individuals with some kind of group identity to fall back upon in the “new society” that they had not chosen and that the Baath leaders were busily creating in Iraq. As civil society disappeared, to be replaced by meaningless party organization, people fell back on the primary groups from which they came as a form of security, or as self-defense, against the suffocating embrace of so much Baathism. But they did so with wariness and out of mistrust.

This new kind of sectarianism is more virulent and more vengeful than the old because it takes effect in an environment where the traditional rules that used to govern sectarian conflict in Faisal’s time have disappeared. The only norms of public behavior that Iraqis have known for a very long time now are those inculcated by the regime. In recent years, incidentally, the Baath officials themselves, particularly in the higher reaches of government, fell back on Sunni sectarianism. They did so not out of conviction but following the same imperative impulse to distrust other groups which they themselves inspired throughout Iraqi society.

The formula of an “Islamic government” or “Islamic republic” is much heard today in and out of Iraq, and it is being bandied about by the most important elements in the Iraqi Arab opposition. This formula, I am convinced, would be interpreted by Sunni Arabs (25 percent of the population) as a Shi’ite attack on them. Therefore, Sunni Arabs will tend to rally around the official Baath apparatus even though they did not want to do so before. Sectarian warfare exceeding in its ferocity anything we have seen in Lebanon is likely to be the result. The ideological politics of the last twenty years would give way to primal loyalties and instincts of self-preservation just as they did in Lebanon. Sectarianism for many people would become the only lifeline to hang onto.

The loss of life could be horrific and the integrity of Iraq as a state would be undermined—if only because no other powerful party now stands for a unified state except the Baath. This is what is starting to happen right now. The insurrection against the Baath is organizing itself spontaneously on ethnic and sectarian lines. In its peculiar way the Baath held all of these forces in check while making the underlying problem of ethnic and sectarian conflict much worse than at any other time in the country’s history.

In these conditions, a genuine secular state in Iraq would acquire its raison d’être and its justification not because it reflected the much-despised secular social values of Western countries, but because Islam in one form or another is still very important in people’s lives.

The stark reality is that genuine, constitutionally guaranteed secularism, with protection against religious and ethnic persecution, is now a matter of survival in Iraq. Iraqis in my view will want it because of their sense of what they have become under the Baath, and of the terrible things that they are capable of. (This is incidentally how secularism came to the West, as a reaction to the European religious wars of the seventeenth century. Over many centuries it turned into something else.)

In Iraq, the need for secularism cannot be dismissed as merely a pious wish; it will have to become a founding principle of the new political order, one that is intimately connected with the preservation of human life and with the integrity of Iraq as a territorial unit. To put it bluntly: the choice in Iraq is between collective suicide and secularism as a form of government.

The same kind of argument can be applied to the idea of a federal republic that could guarantee the Kurdish national minority that their long-fought-for rights will be respected within a sovereign Iraq. The basis of such a federation could be the March 1970 accords that the Baath leaders themselves negotiated with the Kurdish national movement. The main problem with those accords has always been that they were never carried out; otherwise they are a good precedent, one that has always been acceptable to the Kurds. The problem of federalism as a way of securing Kurdish national rights in Iraq, however, is the same as that of democracy. Historically the great foe both of democratic and national rights has always been the Iraqi army. From this fact follows the need for a demilitarized Iraq.

The British imposed upon the former Ottoman provinces that were combined to create modern Iraq two instruments of modernization: an army and a parliament. The parliament survived with various ups and downs for just under forty years. This parliamentary experience, especially during its first two decades, is often dismissed as ineffectual but it was in fact much richer than that. However, in 1958, in the name of “national independence,” the army did away with parliament; and at the same time the army was perceived by many Iraqis as rescuing them from the injustices that prevailed under the monarchy.

By 1991 Iraq had not had a parliament for a period about as long as it had had one before. The logic of the decision to dismantle the parliament in 1958 has finally run its cataclysmic course. The Iraqi army, which was responsible for destroying organized political life in the first place, has during the last ten years hurled an entire generation into ruinous wars. Its entry into political prepared the way for the rule of violence that the Baath and Saddam Hussein perfected as a kind of art form.

This is an army that has only been effective against other Iraqis, especially the Kurds. It performed badly in the Iraq–Iran War and abysmally in the Gulf War. The poison gas attacks on the town of Halabja during the Iraq-Iran War, which killed some five thousand Kurdish civilians, were carried out by units of the Iraqi army. The vaunted Republican Guard, which was built up by the Western press and television as a sort of elite Panzer unit, are largely professional killers whose job during the Iraq-Iran War was to shoot Iraqi soldiers retreating or fleeing from the front lines. Nonetheless, the gargantuan size of the Iraqi army and its modern equipment turned Iraq into a threat to its neighbors twice in the last decade. Those neighbors are therefore justified in fearing Iraq’s military power in the future.

In the meantime the Iraqis’ own experience has taught them not to have any further illusions that the army is a “national savior.” They may still hope that the tattered remnants of the army will turn against the regime of Saddam Hussein, but to support an army that did so would be to choose between the lesser of two evils. Even if it took power, such a discredited army could not hold together the complex society that Iraq has become. Indeed, even if some officers were to succeed in engineering a coup it seems doubtful that the army itself could be held together.

The fundamental problem of the entire system of states created following the collapse of the Ottoman empire is one of legitimacy. The Iraqi army, if it were back in power, would do nothing to achieve a legitimate government. On the contrary it would force the country even further down the road of disintegration. The Baath invented a bizarre and extreme way of legitimizing their rule. They did so by turning fear into the glue of the Iraqi body politic. By the very nature of things this solution was temporary. The insurrections that have been taking place show that the glue is dissolving. The barrier of fear is being broken. However, terrible though it is, fear was effective in holding Iraqi society together. Iraqis desperately need something new today that they can believe in and that will allow them to do constructive work. The time is ripe for bold new ideas. Since the army has been largely smashed, why should it rebuild itself? Why not switch all of those oil resources to postwar reconstruction?

A demilitarized Iraq whose territorial integrity is underwritten by international guarantees would no longer pose a threat to the security of the region and there would be no need for the excessively stringent security arrangements that are now being envisaged by the victors. Moreover Iraq is simply unable to pay the reparations demanded by the United Nations for its destruction of Kuwait. The victors should consider trading the legitimate demands they have made for war reparations for a demilitarized Iraq.

Unfortunately the Iraqi army, with its contempt for democratic politics, still has about it a false aura of strength that responds to deep-seated feelings in Arab political culture. This aura continues to have an effect outside Iraq, among Jordanians and Palestinians, for instance, who, at least for a while, believed that the disintegration of the Iraqi army would diminish so-called Arab strength in relation to Israel. This kind of tribal-nationalist sentiment found its perfect exponent in Saddam Hussein. And if his demise is associated with the emergence of a demilitarized Iraq devoted to postwar reconstruction, such thinking will have been dealt a final blow in the eyes of many Arabs. Iraqis in particular may be less inclined to this sort of militaristic rhetoric in the future. An important task of the Iraqi opposition, therefore, is to discredit the bogus symbolism of brute military strength, to put no confidence whatever in the prospect of army rule in Iraq, and to call for demilitarization as part of the constitutional basis of a new Iraq. Democracy will come to Iraq through demilitarization, or it will not come at all.

Arab political culture is, finally, responsible for having created Saddam Hussein. We who shared that culture cannot escape that responsibility any more than Americans can escape their responsibility for having waged a dirty and excessively destructive war. Like Khomeini, Saddam Hussein is an indigenous creation of the postcolonial “third” world. From the point of view of Arab culture, and of freedom of expression in the Arabic-speaking countries, and above all from the point of view of the sanctity and inviolability of Iraqi and Arab life, Saddam Hussein is the barbarian who has been knocking at the gates. The Gulf War began on August 2, 1990, not January 17, 1991, and it is important that it be remembered in this way. Saddam Hussein was responsible for starting it just as he was responsible for starting the Iraq-Iran War. There can be no new beginning in Iraq or in Arab politics that does not start from this recognition.

A new beginning is possible for Iraqis because they have in a sense plumbed the darkest depths, and looked into the furthest corners of what they themselves are capable of. But I also believe that, with concrete help from outside the country, and before it is too late, this is also the moment when the same Iraqi people are ready to turn around, away from the darkness. Time will tell if this is an empty dream. If so, then the fault will have to be shared between Iraqis themselves and those who have emerged as victors in this terrible war and then failed to help those whom they have crippled.

—March 14, 1991

This Issue

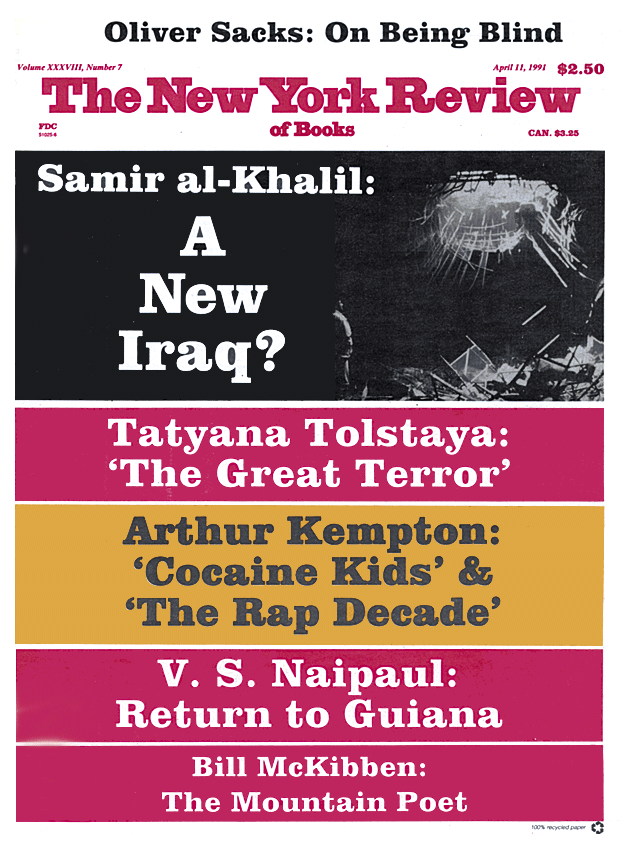

April 11, 1991

-

1

The New York Times, February 27, 1991, p. A7. ↩

-

2

The New York Times, March 1, 1991, p. A11. ↩

-

3

March 18, 1991. ↩

-

4

Quoted by Murray Kempton in New York Newsday, March 3, 1991; see also the report issued by UN headquarters in New York “WHO/UNICEF Special Mission to Iraq, February 1991.” ↩

-

5

See Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (Princeton University Press, 1978), pp. 25–26. ↩