Violeta Chamorro, president of Nicaragua, was the Foreign Policy Association’s guest at breakfast at the Waldorf recently; and her mien and manner stirred the tentative surmise—and indeed the wild hope—that nations ruined by professional politicians might be finding their salvation in amateurs.

Very little is visible in Mrs. Chamorro’s philosophy of government that could suggest pretensions more mischief-makingly lofty than the homemaker’s. Her unassuming virtues cannot, of course, be called house-wifely, because she is that grander presence, the chatelaine.

The Chamorros have an ancient if not always secure lodging among Nicaragua’s ruling families. When her husband Pedro, the publisher, was assassinated by Somocista bravoes, his widow inherited an ancestral house with a variety of mansions. One of her sons was a Sandinista loyalist and another a pillar of the civilian resistance. A nephew was killed fighting with the Salvadoran guerrillas only a few weeks ago.

There is thus room under her protecting wing for a family torn by all the rancors and embitterments that have so long cursed Central America. All her graces arise from a perspective uniquely domestic: she can be fearless in contemplating Nicaragua’s quarrels, and confident of calming them, because she has lived among them at the dinner table.

The hardest thing for most governors is to recognize their people as their family; but nothing seems easier for Mrs. Chamorro, because she can look at her country and see her own household. She beat the Sandinistas in an election no less spiteful than the average these days; and she and the unseated Daniel Ortega at once embraced. Theirs was a scene of reconciliation defying all the history that lay behind it. We owe their miracle to a counterrevolutionary who dared reach out and to a revolutionary who had preserved the human sensibilities he needed to accept her.

Mrs. Chamorro’s government has done better at binding up its country’s wounds than restoring its health, and she couldn’t tell the Foreign Policy Association much of substance. What counted more were those glintings of her spirit that touch the heart. She was asked about Enrique Bermudez, the former contra commander who was assassinated by the usual unknowns in Managua last February. Bermudez was all else but immune to suspicion of thuggery himself, and his intransigence had been no small trial to Mrs. Chamorro. But all the same, as a widow herself, she had flown to Miami to condole with the bereaved Mrs. Bermudez and ask her to suggest nominees for the investigation commission.

“I don’t,” she said from the depths of her own loss, “want any more murders in my country.”

For her any death, friend’s or foe’s, is a death in the family, which is to say that she carries the secret that may be the redemption of troubled people everywhere. What has so often troubled our encounters with women of state in recent years is how like the men of state they seem, and how susceptible to the false masculinity that has been the baneful weakness of politicians everywhere.

But Violeta Chamorro reminds us again of the blessings of what used to be thought of as sensibilities uniquely feminine. The world has been wearied and brought low by movers and shakers; what it cries out for now are healers to whom words like kind and gentle are not rhetoric but the feelings that rule every minute of the day. When Mrs. Chamorro commends the contras who have returned to Nicaragua to gather the bean crop on their new farms, she speaks of these now-peaceful warriors as “boys.” It is the voice of the housekeeper, whose spirit is much more useful as it is more modest than the combat commander’s.

If we listen to that spirit, we may begin to think of all around us as our own family; unless we do, we will break apart and die of loneliness and hatred.

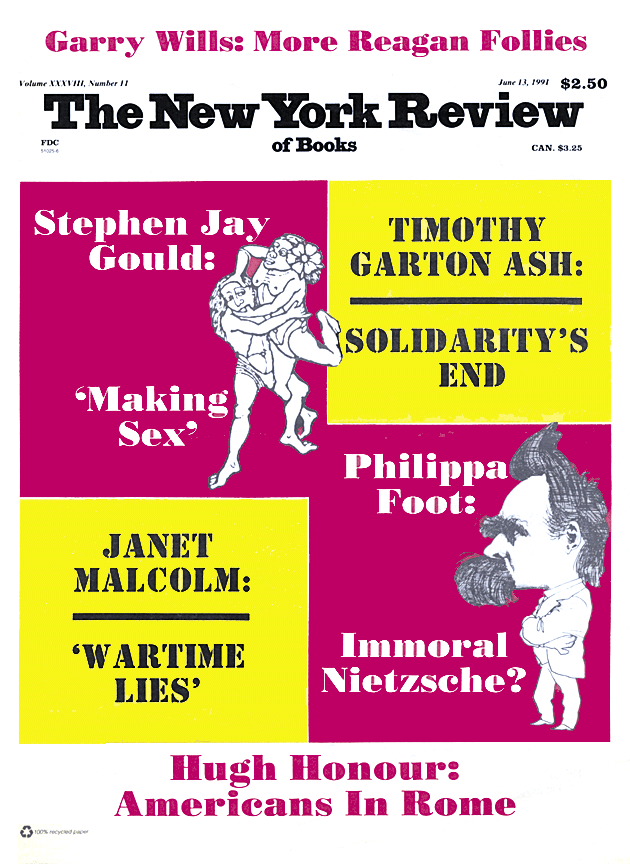

This Issue

June 13, 1991