In March 1980 the poet Heberto Padilla, after futilely asking permission to leave Cuba for some ten years, was summoned by Fidel Castro who told him that he could now go. “Intellectuals,” he told Padilla, “are generally not interested in the social aspect of a revolution.” As early as 1961, at a meeting with artists and writers, Castro defined the role of intellectuals: everything was permissible within the revolution and nothing was permissible against it.

In the early days of the revolution intellectuals such as Padilla were sent abroad as missionaries to convert the European left to become enthusiastic admirers of what was happening in Cuba. Sartre led the chorus of supporters in Paris. But by the mid-1960s there were discordant voices and they found an echo in Cuba itself among those who could no longer “swallow toads,” as the revolution veered off course and assumed many of the features of a police state. As the Egyptian economist Raouf Kahlil, an early admirer of Nasser, told me, there came a time in his country when one could no longer say, “I admire the revolution, but….” In Cuba Fidel Castro’s brother, Raúl, could not tolerate “buts.” Intellectuals, he said, must join the cultural militia of socialist realism. If they refused they must be humiliated into submission. He was convinced that the international travels and contacts with communist intellectuals made them obnoxious because they privately indulged in criticism of the revolution and damaged its reputation abroad. On the other hand, when it was useful, they could conveniently be cast as foreign agents in the pay of the CIA. State Security was the instrument of what Padilla calls Raúl Castro’s “iron-fisted policy.”

All revolutions, as Tocqueville observed, provide a repeat performance of some previous revolution. The Castro brothers were resurrecting Robespierre’s preferred technique: the use of blanket accusations of treason to eliminate enemies of the revolution, who would be denounced by neighborhood committees. The Cuban variant on the Jacobin model was the attack on homosexuals. Revolutionary puritanism, the cult of austerity cultivated by the Sea-Green Incorruptible of 1792, became combined with a conviction that sexual deviants must, by definition, be political dissidents. Even Sartre was troubled about this. “A society without Jews such as Cuba,” he remarked to Padilla, “will end up inventing them. Perhaps the homosexuals are the Jews of Cuba.” 1

The Padilla case was the cause célèbre of Raúl Castro’s campaign against intellectuals. Padilla was a distinguished younger poet in a country where poets abound, sanctified by the revolutionary tradition: José Martí, the martyr-hero of the Cuban struggle for independence against Spain, was a poet. However much his message has been distorted by Castro, he remains the untouchable father of Castro’s own revolution. (Juan Marinello, the leading communist intellectual whom Padilla once admired but whom he later dismissed as a bombastic spokesman for leftist clichés, knew Martí’s speeches by heart.) A common language gives Latin American poets an audience throughout the continent: Neruda is read in Mexico, Octavio Paz in Buenos Aires. And their horizon is not confined to Latin America.

Padilla lacks even a trace of intellectual insularity. Before the revolution, while briefly living in New York, he translated St.-John Perse and visited him in Washington. In his Self-Portrait he describes how in the early 1960s he became a friend of Yevtushenko and other Russian poets when he was sent to report for Prensa Latina from Moscow. He goes to Juan Goytisolo’s parties in Paris; he talks at length with Sartre in Moscow. It is in Europe, not in the Americas, that he hears “the noise of the world,” and it is there that the ideological battles of the left were fought out after the denunciation of Stalin at the Twentieth Congress. The central question when he talks privately with Europeans is what, if anything, can be rescued from the failure of utopian socialist hopes. He even rejects the Cuban landscape as suitable for poetic treatment; he finds his inspiration in Lapland and is moved by the French countryside glimpsed from a train window on the way to visit Camus.

After several years in Europe and the Soviet Union as a correspondent, Padilla returned to Cuba in 1963 only to start again on his travels again as a director general of the Ministry of Foreign Commerce, a witness to Castro’s habit of capriciously interfering with the regular bureaucracy by sending his own “special missions” abroad. Back in Cuba in 1964 his troubles began. First he identified himself as unreliable by defending the novelist Cabrera Infante, who was on the verge of disgrace before becoming the most virulent of Castro’s literary enemies. Then Padilla surreptitiously entered the competition for and won a national poetry prize awarded by an international jury for his collection of poetry with the irritatingly disengaged title Fuera del Juego (Out of the Game). Predictably this minor victory made him detestable to the military bureaucrats, but the communist literary establishment also could not tolerate so independent a writer getting the prize and international attention. He was ostracized and constantly attacked. In fact, his criticism of the regime was usually oblique, ironic, cautionary; but it was deeply skeptical of the kind of revolutionary propaganda the literary bureaucrats were promoting. Fuera del Juego, for example, included the short poem “The Old Bards Speak”:

Advertisement

Don’t you forget it, poet.

Whatever the place and time

in which you make or suffer History,

there will always be a dangerous poem to ambush you.

—translated by Mark Strand

Padilla, moreover, made a dangerous friend in Jorge Edwards, the Chilean ambassador under Allende, and bon vivant in a gray world, a Bohemian dispenser of liquor to deprived Cuban intellectuals at the Chilean embassy. In Edwards’s account of his stay in Cuba Padilla appears as a “desperate, self-destructive being,” presumably because he talked openly of being fed up with the regime, or perhaps because he tried to send out of the country his novel Heroes are Grazing in My Garden, a book published in Spain in 1981, which he describes as “not a denunciation or an allegation, not even testimony…” but “a text through which certain conflicts and certain beings pass like shadows.” He was arrested by state security in 1970, humiliated, beaten up by jailers to the rhythms of his own poetry, confronted by tapes of his conversations with Edwards, injected with hallucinatory drugs, and was paid a gloating visit by Castro himself (“Today I have time to talk to you, and I think you have the time, too….”) This treatment, Padilla hints, was not so much a crude revenge for his winning the poetry prize as an attempt to show, as his interrogator put it,

We have to put an end to the problem of intellectuals in Cuba. Otherwise, we’ll end up just like Czechoslovakia, where the intellectuals are standard-bearers Fascism….

Padilla signed a “confession” to being a spy, which he recited in public at a meeting of the Writers’ Union.

The whole affair was a gross blunder on the part of the authorities. The brutality of the intelligence services, even if milder than that in Eastern Europe, was matched by their stupidity in imagining that a Stalinist-style confession would pacify international criticism of the plight of Cuban intellectuals. The almost farcically exaggerated language of Padilla’s confession was immediately recognized abroad as being forced and phony, as he evidently expected. His interrogator, one of the minor bullies who flourish in authoritarian regimes, harped on Padilla’s international connections and said sarcastically, “there might be a gigantic international reaction.” There was. Sartre took the occasion of the confession finally to denounce the regime. Most moving of all was a telephone call—monitored, of course—from the Spanish communist poet Blas de Otero.

José Lezama Lima, the elderly Cuban poet so prestigious that he could not be touched and who had been instrumental in awarding Padilla the poetry prize, also stood by him. The social realists of the regime detested Lezama’s baroque aesthetics—he followed the poets of seventeenth-century Spain, for whom “the difficult is beautiful.” (Lezama’s very obscurities offered state security little opportunity to entrap him. An informer or wire tapper would only be bewildered by his complex metaphors and arcane literary allusions.) Like Virgilio Piñera, a major Cuban poet who suffered from persecution as a homosexual, Padilla became a non-person, his voice silenced. He was allowed to eke out a living as a translator. His only desire was to leave Cuba. In the end it was his international connections—his crime in the eyes of the state security—that got him out. His friends, the New York Review editors among them, enlisted powerful support.

Padilla’s problem was one that, sooner or later, faces virtually all intellectuals caught up in a revolution. When do you resist the drift toward tyranny—Padilla does not hesitate to call Castro a tyrant—of a revolution that initially burst on an unjust society as a liberating force? For Burke, the moment of truth during the French Revolution came early with the creation of a unicameral chamber that was determined to cut France off from its historic past in the name of the abstract principles of “sophisters, economists, and calculators.” For most others it came with Robespierre and the Terror. When did the Cuban revolution take the wrong turn? Was the tendency to dictatorship already latent in the televised treason trials of 1959, and did it become patent with Castro’s execution of his old comrades in arms from the Sierra Maestra? Or with his cruel jailing of Huber Matos soon afterward, when Matos expressed his dismay at increasing communist influence on the revolution? Or when another old comrade of Castro’s, Major Plinio Prieto, was shot to death on the standard charge of being a CIA agent? Or was it Raúl Castro’s “militarization of culture” on the Chinese model that made the air of Cuba foul and unbreathable?

Advertisement

Padilla writes that when he went on missions abroad in the 1960s he found the embassies full of “brawling cats”—brawling in part over the growing failures of communism and the revolution back home. He chose to live in Moscow, “convinced at the time that in this far-off land I would be able to glimpse the outlines of Cuba’s future.” The glimpse afforded no comfort: he observed Khrushchev’s outburst against decadent art and then heard it defended by the Party intellectuals in Paris. He was told how Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony, with a text by Yevtushenko, was banned at the last moment by the Stalinist apparat that survived the Twentieth Congress. Yevtushenko claimed that, appearances to the contrary, after the Twentieth Congress the Party would continue on to its logical, democratic conclusion. “I know that one day it will do it. We must not be pessimists.” But the Cuban leaders, Padilla told him, were not interested in the truth about Stalin. Fidel had already legitimized the “Stalinist authoritarian style on the pretext that the enemy was only ninety miles away.” Padilla had become a pessimist.

Already in 1959 Camus told Padilla that he was worried about certain signals coming from the island. “I only wish,” Padilla writes “that these signals which he perceived had been as visible and as alarming to me as they were to him.” The Argentinian novelist Julio Cortázar, later to defend Padilla against persecution, warned of the shadow of the guillotine. But Padilla, to his credit, acknowledges that he was still caught in an emotional and political trap of his own devising: to criticize the revolution was to side with the evils of Western colonialism.

This was the same trap that ensnared Alejo Carpentier, a novelist whom I much admired. When I met him, we talked for hours about Proust—like me, he used the more tedious passages of The Captive as a cure for insomnia. To see this wonderfully intelligent man, who wrote a novel that describes the Jacobin degeneration of a revolution, warmly embracing Castro two days later was a painful experience. But Padilla’s last conversation with Carpentier, by then a sick and dying man, gives a clue to his thinking.

“I’ve got no choice but to stick with the left,” he said, “You are to blame for everything that has happened to you…. We can’t get into a fight with the left even though it is lame, one-eyed, and ugly.”

When García Márquez came to Havana Padilla appealed to him to put in a word that might get him out of Cuba. “I should tell you,” García Márquez said,

“that I am the first to criticize this revolution.”

“But you haven’t been invited here [Padilla told him] because of your criticism. We would all like to say what we feel, but you have been invited because you grew closer to the Revolution just as the majority of writers abroad stopped supporting it.”

He kept moving his leg up and down. I saw he had on maroon boots of tanned leather. They were very popular in Spain at that time.

“You are right in thinking that I can help you,” he said slowly, “but I won’t. I think you should think it over. Your leaving Cuba this moment would harm the Revolution.”

Padilla finishes his book with such quietly bitter observations. He sticks to the facts of his own Cuban experiences and says little about life in exile or his sense of the future. Since he left, the opposition of brave men, including some of the military heros of the Angolan War, appears to have done little to shake Castro’s hold on the Cubans—though without free elections, for which organized mass meetings are no substitute, his real popularity must, at best, be a matter of guess work. He is still able to hold on to power in the face of the shock waves from Eastern Europe. His inflexibility is the despair of advisers who see the disasters of his economic policies. With the USSR no longer willing to supply fuel and other products on the same subsidized terms, he demands yet more of the austerity that has reduced Cuba to a society of empty shops. Austerity based on continually cutting consumption is not a formula for development. Just as Cuba was the last bastion of Spanish imperialism it promises to be the last bulwark of oldstyle communism.

What Castro seems to offer is a very limited version of glasnost without perestroika. Some criticism of bureaucratic shortcomings may be allowed, even encouraged, but only within the assumptions of one-party socialism. As yet there is little sign of popular revolt gathering force in response to the declining living standards; those who can stomach it no longer have to take the risks of escaping from the island. Castro’s personality cult apparently does not need the support of the banks of computer files of the old East German Stasi. Primitive techniques for bugging apartments and a host of informers and local “committees for the defense of the revolution” supply state security with all the information it needs to clamp down on dissent. Cuba is a face-to-face society where every town and village has seen the Maximum Leader, and above all heard him—since 1959 Castro has made on average one speech every four days. He insists on the threat of another Bay of Pigs and a manipulated war mentality has, as Raúl Castro planned, turned Cuba into a militarized society.

Castro hopes, by attracting US tourists, to provide much-needed foreign exchange. But the tourists bring with them the attractions of a consumer society only ninety miles away. The young, as their protest songs reveal, resent their exclusion from hotels and enjoyments reserved for tourists precisely because they want a taste of consumerism; the sunglasses, the jeans, the records that are unavailable at home. It is not that they reject the doctrines of the revolution but that they resent the restricted style of life that is the consequence of their application.

Indoctrination in Cuba plays on an intense nationalism that has made Cuba at times an awkward ally of the Soviet Union. As a compensation for the denial of the enjoyments of Western capitalist consumer societies, the defenders of the regime constantly call attention to the neglect of the poor in other countries of Latin America; and Castro accuses Western intellectuals of overlooking the social achievements of his revolution which, by the standards of most Latin American countries, are impressive among the poorer agricultural workers. According to official Cuban statistics, since the revolution infant mortality has dropped from sixty per thousand live births to thirteen by the 1980s, and average life expectancy has risen from fifty-seven to seventy-four years. Illiteracy has dropped from 24 percent to 2 percent.2 What the newly literate are allowed to read is another matter; and what urban Cubans are aware of is a decline in every aspect of their life.

It is not surprising that a large proportion of the population has chosen to leave and each week people continue to risk their lives to do so. Among all the other uncertainties that will affect the country’s future, not the least will be the fantasies of its exiles.

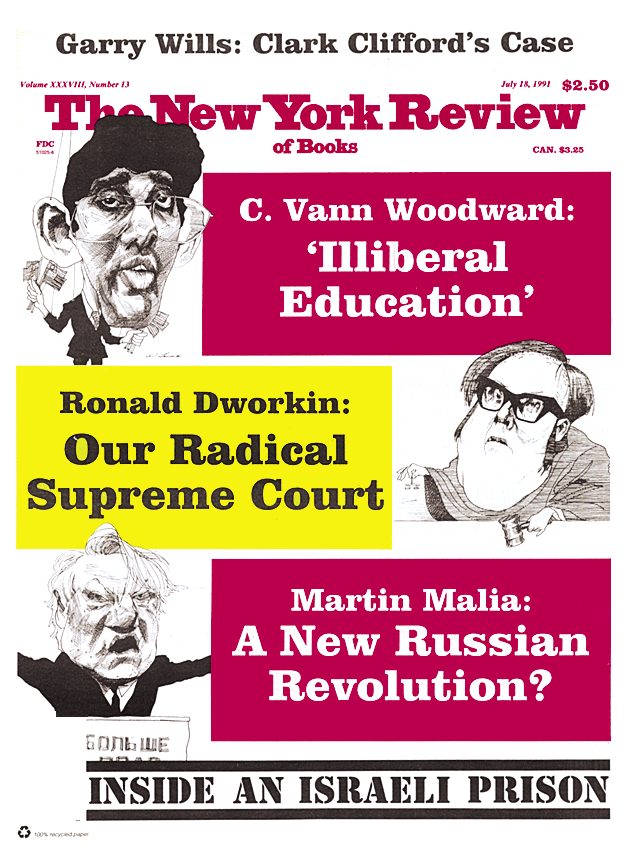

This Issue

July 18, 1991

-

1

Fidel Castro seems to have been prejudiced against homosexuals for many years. In 1954 Batista’s minister of the interior accused Castro’s wife of being in the pay of the ministry. Castro’s reply was that “Only an effeminate, sunk in the last rung of sexual degradation, could stoop to such a step.” This prejudice may have been intensified by the macho image Castro fostered in the guerrilla struggle of the Sierra Maestra. ↩

-

2

A skeptical view of such claims can be found in Nick Eberstadt, The Poverty of Communism, Chapter 9 (Transaction Publishers, 1988). He argues that, in view of the relatively high literacy rates and low infant mortality rates in 1959, revolutionary Cuba “has not fared better than most other affluent Caribbean and Latin American societies.” ↩