Near the end of his short life, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that he “had been only a mediocre caretaker of most of the things left in my hands, even of my talent.” It was his short stories, written to make money, that, he felt, had been the major dissipation:

I have asked a lot of my emotions—one hundred and twenty stories. The price was high, right up with Kipling, because there was one little drop of something not blood, not a tear, not my seed, but me more intimately than these, in every story, it was the extra I had. Now it has gone and I am just like you.

In his lifetime Fitzgerald promoted the view of his stories as hack work, simultaneously bragging and abasing himself to Hemingway, confessing how much he was being paid by the Saturday Evening Post and how much he despised the product. “Here’s a last flicker of the old cheap pride: the Post now pays the old whore $4000 a screw,” he wrote to Hemingway in 1929.1 While the story in question, “At Your Age,” deserves only slightly better, Fitzgerald also dismissed good stories like “Bernice Bobs her Hair,” telling Mencken that it was trash.

In view of how much has been written about Fitzgerald since his death, there has been scant discussion of the short stories. Edmund Wilson refers broadly to his “rather inferior magazine fiction.” Yet one pleasure of rereading Fitzgerald’s stories now is to rediscover just how good some of them in fact are, and how brilliant a handful. One problem is that there were far too many: 160 stories in a brief life—some of them really novellas—of which forty-three are included in Matthew Bruccoli’s recent edition, an almost 800-page volume which will discourage bedtime reading in those without great upper-body strength. Hemingway, by contrast, published forty-nine and Faulkner about fifty.

The standard collection of Fitzgerald’s stories to date has been Malcolm Cowley’s 1951 edition with twenty-eight stories. Cowley’s Fitzgerald is a realist in method if not in sensibility (with the stunning exception of the fabulist “Diamond as Big as the Ritz”), and very much the author of The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night. Cowley included the indisputable jewels. “Diamond…,” “The Ice Palace,” “Winter Dreams,” “May Day,” “Absolution,” “The Rich Boy,” “Babylon Revisited,” and “The Bridal Party.” Bruccoli’s huge collection, on the other hand, with almost twice as many stories, complicates, and lightens, Cowley’s picture. Bruccoli’s Fitzgerald is more fanciful. He is clearly the man who wrote nonsense lyrics for Princeton Triangle productions, and later tossed Gerald Murphy’s prized Venetian goblets over the wall of the Villa American just to hear the sound of the crystal breaking on the stones of the courtyard. (Cheever, so similar in other ways, has some of this mischievousness.) He’s more consciously an entertainer, to the point of turning tricks with the supernatural, as in “A Short Trip Home,” the story of a seedy ghost who nearly ensnares the soul of a Midwestern debutante. Many of the stories Bruccoli has included would be happiest wearing the label of “tales,” or “romances.” Their writer is also not above trick endings, and you can see him in the earlier stories all too obviously trying to charm. We can also see him straining desperately for that ebullience in the stories of the Thirties, as his output trails off. “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz” makes more sense in this company, even as it towers over the other romances in Bruccoli’s selection.

Almost all of the stories Bruccoli has collected have been republished in one form or another elsewhere. To judge by back issues of the Saturday Evening Post and Colliers, the quality falls off very sharply beyond this material. “Last Kiss” (1940) is the only one Bruccoli has included that was never published in Fitzgerald’s lifetime, and has never appeared in a book before. Set in Hollywood, it is a sentimental story about a producer and a beautiful and spirited English actress, whom he lets down. The main character strongly resembles The Last Tycoon’s Monroe Stahr, but the portrait here is full of self-hatred.

Bruccoli has included more stories from the middle of Fitzgerald’s career, between Gatsby and Tender Is the Night (1934). One I have never encountered before, “The Bowl” (Post, 1928), is a wildly romantic portrait of the athletic hero Fitzgerald worshipped all his life. “The Baby Party,” included in Dorothy Parker’s brilliant small selection of stories in the 1945 Viking Portable Fitzgerald, as well as in Cowley, has regrettably not made the cut. The story of a fiercely competitive suburban birthday party that erupts into a long bloody punchout between two fathers fresh from the commuter train, it is one of the funniest stories Fitzgerald wrote, and at this distance a rough prototype for the coolly ironic suburban tales that were later to flourish in The New Yorker.

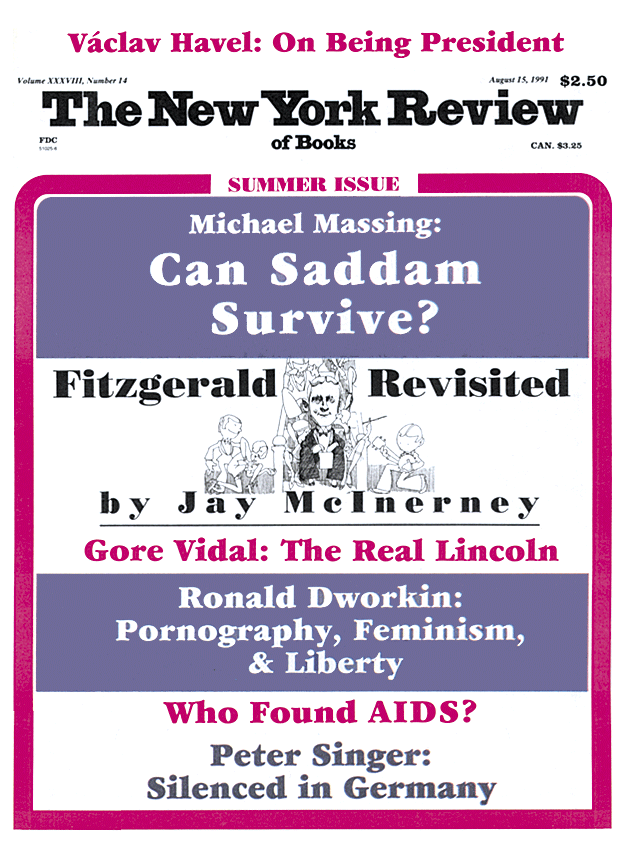

Advertisement

Some of Bruccoli’s weakest entries seem to be included only to demonstrate Fitzgerald’s “range”—the mechanical, puerile “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” (1922), for instance, which is about a man who enters the world in the body of an old man and who grows backward into maturity, youth, and infancy, or “Dearly Beloved” (1940), a short and pointless sketch of a black train steward and a golf champion. “Life is much more successfully looked at from a single window,” Nick Carraway tells us, and Fitzgerald’s best work rarely strays from that view. Bruccoli seems to want to punch new openings in the facade. “The appellation ‘a typical Fitzgerald story’ is useless,” he says, and includes far too many second-and even third-rate stories.

“Head and Shoulders” (1920), the first story in Bruccoli’s collection, was also the first story Fitzgerald sold to the Saturday Evening Post and it is in some ways characteristic of what Post readers—many of whom never read a Fitzgerald novel—would come to expect of him. Its scheme is preposterous, and also charming: a child prodigy philosophy scholar meets a chorus girl and marries her. They call themselves Head and Shoulders—he’s the brain and she does the shimmy onstage. By the end of the story they have reversed roles—she has written a best-selling book and he is working as a gymnast. The story farcically rehearses the arc of Tender is the Night and its theme of role reversal, in which the wife vampirishly drains her husband’s vitality. Passed over by Cowley for obvious reasons of quality, the story is interesting nevertheless as an example of an early stage in the development of Fitzgerald’s narrative techniques and style:

And then, just as nonchalantly as though Horace Tarbox had been Mr. Beef the butcher or Mr. Hat the haberdasher, life reached in, seized him, handled him, stretched him, and unrolled him like a piece of Irish lace on a Saturday-afternoon bargain-counter.

The familiar narrative voice at this early stage in Fitzgerald’s career is teasing, perhaps a little pushy; yet even here the voice, whether first- or third-person singular, is so disarming as to be capable of convincing the reader of almost anything. It is sophisticated without being superior, conspiratorial without the gossip’s malice. It is the nascent voice of Nick Carraway, who carries us past the improbabilities and gaps in Jay Gatsby’s background with such assurance that we are unlikely to notice them.

In “Head and Shoulders” we see in its earliest development one of Fitzgerald’s greatest gifts as a storyteller—the conversational intimacy of his narrative voice. Fitzgerald’s third-person narratives always sound as if they are verging into the first person, as indeed they sometimes do in the stories, the author stepping in from out of nowhere (almost like a latter-day Henry Fielding). “Now in Hades—as you know if you ever have been there….” “It is with one of those denials and not with his career as a whole that this story deals….” “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.”2 In this regard Fitzgerald is something of a throwback. While modernism was striving for impersonality, and while Joyce, copping an attitude—and a metaphor—from Flaubert, was refining himself out of the text, F. Scott Fitzgerald never disappeared from his stories. They were entirely personal, intimate, and confidential. (Which is perhaps one reason why Fitzgerald’s critics have always been so personal, so much under the spell of his biography.)

The Thackeray of Vanity Fair comes to mind when one reads the early stories, the genial, coy, semi-omniscient narrator who sometimes avails himself of the first-person pronoun and who pops onto the stage toward the end of the book. As a satirist he is delicate: in exposing hypocrisy he is inclined merely to wink complicitly at the reader without necessarily thrashing the hypocrite to death:

There are things we do and know perfectly well in Vanity Fair though we never speak of them, as the Abrahamians worship the devil, but don’t mention him: and a polite public will no more bear to read an authentic description of vice than a truly refined English or American female will permit the word breeches to be pronounced in her chaste hearing.

Compare this with a passage from “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” Fitzgerald’s fourth Saturday Evening Post story, published in May of 1920.

It is well known among ladies over thirty-five that when the younger set dance in the summer-time it is with the very worst intentions in the world, and if they are not bombarded with stony eyes stray couples will dance weird interludes in the corners, and the more popular, more dangerous, girls will sometimes be kissed in the parked limousines of unsuspecting dowagers.

If the first half of this passage seems a little too easy in establishing a nudging rapport with the reader, the couples dancing “weird interludes in the corners” and “kissing in the parked limousines of unsuspecting dowagers” have Fitzgerald’s characteristic sparkle.

Advertisement

It is exhilarating to reread these early stories and see Fitzgerald flexing his talent. “May Day” (1920) shows the influence of Sister Carrie without sounding like anything but early Fitzgerald.

Fifth Avenue and Forty-fourth Street swarmed with the noon crowd. The wealthy, happy sun glittered in transient gold through the windows of the smart shops, lighting upon mesh bags and purses and strings of pearls in gray velvet cases; upon gaudy feather fans of many colors; upon the laces and silks of expensive dresses; upon the bad paintings and fine period furniture in the elaborate show rooms of interior decorators.

Working-girls, in pairs and groups and swarms, loitered by these windows, choosing their future boudoirs from some resplendent display which included even a man’s silk pajamas laid domestically across the bed.

The omniscient narrative presents a panoramic view of the city which moves effortlessly between a suite at the Biltmore, the offices of a radical newspaper, and the thronged streets. Eight or nine characters from diverse social strata are deftly sketched. There is a young plutocratic Tom Buchanan prototype, Philip Dean, who, after a bracing shower, would “[emerge] from the bathroom polishing his body.” At the other end of the social scale are two recently demobilized soldiers.

Leaving the café they sauntered down Sixth Avenue, wielding toothpicks with great gusto and complete detachment.

“Where to?” asked Rose in a tone which implied that he would not be surprised if Key suggested the South Sea Islands.

Interweaving stories of the two toothpick-wielding soldiers and a Yale class reunion, “May Day” is one of the few works besides Gatsby that show a genuine facility with plot, and it is also one of the few besides Gatsby that portray the lower classes. Fitzgerald here seems to have borrowed an uncharacteristic determinism from the Naturalists, particularly Dreiser. Gus Rose and Carrol Key, the two recently demobilized “sojers” whose paths intersect with several well-to-do citizens over the course of May Day, are “poor, friendless; tossed as driftwood from their births, they would be tossed as driftwood to their deaths.” Edith Bradin, one of Fitzgerald’s classic debutantes, is told by her socialist brother “you’re young and you’re acting just as you were brought up to act.” And Gordon Sterrett, the writer of the story, a dissipated would-be commercial illustrator, is crushed by poverty as well as by weakness of character. The story ends when he shoots himself after waking up in a cheap hotel room with the lower-class, “over-rouged” Jewel Hudson, who has been simultaneously courting and blackmailing him. Although it relies partially on Fitzgerald’s prudish, gentlemanly assumption that one is “irrevocably married” to a woman with whom one wakes up in the same bed, the suicide at the end of the story is surely intended to be the inevitable consequence of Gordon Sterrett’s surrender to economic conditions and his psychological predisposition. As with The Beautiful and Damned the intermittent, mechanical determinism here seems often at odds with Fitzgerald’s romanticism, and he would later discard it. He came to believe in what Nick Carraway refers to as “character,” and in the ceaseless, potentially tragic struggle of the individual will to impose itself on the natural and social order.

Fitzgerald must have felt the material was too strong for the Saturday Evening Post; he sent it to H.L. Mencken’s Smart Set, which paid him $200. While Fitzgerald’s career was associated closely with the Post, to which he sold sixty-five stories in his lifetime, his strongest stories tended to appear elsewhere. “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz” (1922) was also published in Smart Set after being rejected by the Post, which at that time was paying him $1,500 for his more conventional stories.

You have to go back to Washington Irving or to the tales of Hawthorne—to, say, “Rapuccini’s Daughter”—to find anything like “Diamond” in American literature. It can be read as an allegorical treatment of the corrosive effect of great wealth, with “The Rich Boy” as the realistic treatment of the same theme. But the exuberant delight in its own excess makes “Diamond” something both more and less than an allegory. It begins with Fitzgerald’s jauntily reassuring narrative voice asking us to check our disbelief at the door. John T. Unger, from Hades, is sent east to school.

St. Midas’ School is half an hour from Boston in a Rolls-Pierce motor car. The actual distance will never be known, for no one, except John T. Unger, had ever arrived there save in a Rolls-Pierce and probably no one ever will again.

Earnest hick John goes home for the holidays with Percy Washington, who brags that his old man, “has a diamond bigger than the Ritz-Carlton Hotel.” From this moment on the prose swells to catch up to this hyperbole, throbbing like an adolescent’s heartbeat: “The Montana sunset lay between two mountains like a gigantic bruise from which dark arteries spread themselves over a poisoned sky.” The overripeness here is more clearly measured to its purpose than in This Side of Paradise. Excess is its subject. John T. Unger falls in love with the young daughter of the fabulously wealthy Mr. Washington. But in Fitzgerald’s stories poor boys are not gladly tolerated by rich fathers and Mr. Washington plans to kill John T. Unger until a squadron of planes attacks his diamond mountain, allowing John T. to escape with the young princess. As an undergraduate I remember finding this novella “childish” and preferring the more realistic stories—but it has improved with age (mine), and with my exposure to magic realism; while it seems almost sui generis, Fitzgerald’s fantastic tale of the American West would hardly be out of place in an anthology of Latin American fiction.

While even the weaker stories Bruccoli has included illustrate the development of the mesmerizing voice of Nick Carraway, some of the ostensibly commercial stories give in bald outline the archetypal Fitzgerald plot which underlies his greatest work. Like “Diamond,” “The Offshore Pirate” and “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr-nce of W-les,” collected here, are also fairy tales about a worthy young man resorting to disguise and pretense to win the affection of a spoiled beauty. Fitzgerald once said he preferred the gimmicky “Offshore Pirate” to “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” a preference about which we can only say that there are a few powerful exceptions to the rule that he was his own best critic. A young suitor posing as a desperado boards a yacht and kidnaps the gorgeous brat on board. By the time the authorities catch up with him the brat has fallen in love with the pirate, who reveals that he staged the incident and invented his criminal background. “What an imagination!” the girl responds when she learns of the deception. “I want you to lie to me just as sweetly as you know how for the rest of my life.” At the end of this tale about tall tale-telling the heroine winks at the audience and steps out of the frame of the story and the column of the magazine in which she appears and “kissed him softly in the illustration.”

In “Rags Martin-Jones and the Pr-nce of W-les” (1924), the eponymous hero wins the beautiful flapper by staging a similarly elaborate hoax in which an actor poses as the Prince of Wales. The second story is obviously a reprise and seems to me no better than a handful of others that might have been lifted out of back issues of the Post—“The Unspeakable Egg,” for instance, about a young heir who poses as a beach bum in order to win a debutante. It is ironic that Fitzgerald had such trouble writing for Hollywood, since both of these stories are much like extended treatments for the romantic screen comedies of the Thirties. Stylish and stylized, they are much less realistic than Gatsby or “May Day,” but hardly more farfetched than the story of Fitzgerald’s own courtship of Zelda. In that story the young demobbed officer rejected by the Southern beauty crawls home to St. Paul to concoct a long romantic story called This Side of Paradise, which instantly wins him fame, fortune, and the girl. Near the end of his life, looking back, he wrote:

My friends who were not in love or who had waiting arrangements with “sensible” girls, braced themselves patiently for a long pull. Not I—I was in love with a whirlwind and I must spin a net big enough to catch it out of my head, a head full of trickling nickels and sliding dimes, the incessant music box of the poor. It couldn’t be done like that, so when the girl threw me over I went home and finished my novel. And then, suddenly, everything changed….

A sudden reversal of fortune brought about by an act of will or imagination—this was the story, too, of Fitzgerald’s early life, a life which at this point is so familiar and shapely it nearly obscures the independent virtues of his fiction. Just in the past decade we have had at least two biographies, Bruccoli’s hagiographic Some Sort of Epic Grandeur and James R. Mellow’s peevish, sordid Invented Lives, as well as Scott Donaldson’s folksy psychoanalysis in Fool for Love, which join the Fitzgerald shelf already sagging with Arthur Mizener’s excellent and grim The Far Side of Paradise, Andrew Turnbull’s biography memoir Scott Fitzgerald, and Nancy Milford’s feminist revisionist Zelda. What doesn’t emerge from any of these books is the sense of a coherent personality. We can imagine Fitzgerald drunk, or sad, or zany, but the moods don’t coalesce into a real human being with a drink and a cigarette in his hand.

The man we hear in the stories is not there in these books—not in the way that we feel him present in even a minor story like “Head and Shoulders.” Fitzgerald himself suggested the solution to this enigma, in his note-books: “There was never a good biography of a good novelist, there couldn’t be. He is too many people if he’s any good.” In the meantime, we know too much about Fitzgerald’s life and too often tend to read the fiction as its reflection. In a copy of Tender is the Night which I picked up at a second-hand bookstore, alongside a passage in which the author sketches Dick Diver’s feelings about Nicole’s sickness, the former owner has written: “Reflects Fitzgerald’s real feelings about his own wife (Zelda).” How this commentator distinguished Fitzgerald’s “real” feelings from his false ones is not clear, but I don’t believe his literary appreciation has been much enhanced. One of the pleasant surprises of rereading the stories is to discover that Fitzgerald’s strongest short fictions—“May Day,” “The Rich Boy,” “Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” and “Absolution” may be among his least autobiographical.

Still, the young (poor) boy’s quest for the hand of the beautiful, rich princess is undoubtedly Fitzgerald’s best plot, the fairy-tale skeleton of his jazz age tales. One supposes that magazine editors preferred the stories in which the quest is successful, but in the better ones, like “Winter Dreams” (1922) and “‘The Sensible Thing”‘ (1924), the success is qualified or the quest ends in failure. It is also the plot of Gatsby, in which Nick Carraway imagines himself into Gatsby’s fantasy of Daisy Buchanan. “High in a white palace the king’s daughter, the golden girl….”Daisy is the enchanted princess for whom Gatsby performs his heroic labors.

In “Winter Dreams” (1922), the princess is the selfish, spoiled Judy Jones, who gives shape to the ambitions of the poor boy, Dexter Gordon. The son of a grocer, Dexter quits his job as a caddy at the snobbish Sherry Island Golf Club rather than carry the bag of eleven-year-old Judy Jones, a brat who thrashes the fairway and her nurse with a seven iron, “beautifully ugly as little girls are apt to be who are destined after a few years to be inexpressibly lovely and bring no end of misery to a great number of men.” Dexter cannot articulate to himself, let alone the caddy master, the adolescent passions and insecurities that underlie his sudden decision to quit. When Dexter next encounters Judy Jones he is the guest of a club member, having worked his way through a prestigious university in the East, and returned to Sherry Island to open a successful chain of laundries. In the intervening years Judy has become as beautiful as feared; later she invites Dexter to drive her speedboat and even to kiss her, putting him into rotation with a dozen other desperate suitors. When, after a year and a half, Dexter tires of being manipulated and becomes engaged to a “nice” girl with a “great personality,” Judy comes back into his life long enough to wreck the engagement and Dexter’s social standing. Years later, successful on Wall Street, he is astonished to hear a visiting business associate from the Midwest refer to her as an object of pity, the faded victim of an unfaithful, alcoholic husband.

He had gone away and he could never go back any more. The gates were closed, the sun was gone done, and there was no beauty but the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time: Even the grief he could have borne was left behind in the country of illusion, of youth, of the richness of life, where his winter dreams had flourished.

A story which conforms to no previous pattern, “Absolution” (1924), was at one time to have served as the prologue to an early version of The Great Gatsby. Rudolph Miller is a Dakota schoolboy who creates in his daydreams a suave alter ego named Blatchford Sarnemington. This young dreamer, a Catholic, tells the priest one day in confession that he never tells lies, thereby committing the mortal sin of lying in confession, a sin he compounds by taking communion the next day. Rudolph finally confesses his sins to Father Schwartz, whose mind is rapidly disintegrating under the strain of his exile from the world and the repression of his sensual nature:

He wept because the afternoons were warm and long, and he was unable to attain a complete mystical union with our Lord. Sometimes, near four o’clock, there was a rustle of Swede girls along the path by his window, and in their shrill laughter he found a terrible dissonance that made him pray aloud for the twilight to come.

When Rudolph tells Father Schwartz his terrible secret, the priest is silent as the clock ticks in the rectory, until he responds, in a peculiar voice, “When a lot of people get together in the best places things go glimmering.” Attempting to explain, he continues: ” ‘Do you hear the hammer and the clock ticking and the bees? Well, that’s no good. The thing is to have a lot of people in the center of the world, wherever that happens to be.’ Then—his watery eyes widen knowingly—’things go glimmering.’ ” Given Fitzgerald’s notoriously casual grasp of spelling I can’t help wondering if “glimmering” was exactly the word intended here, or whether “glistening” and “shimmering” might not have been confused somehow; yet the word seems perfect for the priest’s rambling thoughts.

As Father Schwartz continues, Rudolph becomes frightened, realizing the priest is crazy:

But underneath his terror he felt that his own inner convictions were confirmed. There was something ineffably gorgeous somewhere that had nothing to do with God. He no longer thought that God was angry at him about the original lie, because He must have understood that Rudolph had done it to make things finer in the confessional, brightening up the dinginess of his admissions by saying a thing radiant and proud. At the moment when he had affirmed immaculate honor a silver pennon had flapped out in the breeze somewhere and there had been the crunch of leather and the shine of silver spurs and a troop of horsemen waiting for dawn on a low green hill.

The gorgeous lies of the imagination triumph again over dull fact. Fitzgerald realized that this prologue “interfered with the neatness of the plan” of Gatsby and discarded it, yet in spite of its origin, it can stand alone as one of his more sustained and powerful stories.

If many of these early stories have an almost puppyish exuberance, those of the Gatsby period wear their wisdom lightly; Nick Carraway is given to seemingly effortless aphorism, and to oxymoron—those ostensibly contradictory figures of speech which move in two different directions at once. Nick affects a “hostile levity” to fend off bores; the gambler Meyer Wolfsheim eats with “ferocious delicacy”; Daisy’s much described, money-full voice is a “wild tonic,” and later sounds “a clear artificial note”; Tom Buchanan, after triumphing over Gatsby and Daisy, dismisses them with “magnanimous scorn,” and later attends to a grieving husband with “soothing gruffness.”

Around 1924 and 1925, Fitzgerald’s style briefly achieved the amazing compression that gives Gatsby its depth of feeling and complexity. It is this style that makes the first long story written immediately after Gatsby seem like a novel. Ring Lardner, a master of compression himself, felt that “The Rich Boy” should have been a novel. If “Diamond” trades in broad strokes and types in its examination of American wealth, “The Rich Boy” moves in the opposite direction. “Begin with an individual and before you know it you find that you have created a type; begin with a type, and you find that you have created—nothing.” The nameless first-person narrator, like Nick Carraway, has a gift for aphorism and his narrator a conversational ease that masks the story’s density. Anson Hunter is one of Fitzgerald’s richest portraits, a complex, more sympathetic version of Tom Buchanan. The determining fact of his character is his money, which prevents him from loving another human being, just as having been born lucky prevents him from being a tragic figure on Gatsby’s scale. This may be the reason for Fitzgerald’s certainty that “it would have been absolutely impossible for me to have stretched ‘The Rich Boy’ into anything bigger than a novelette.”

Anson Hunter is anything but a representative figure:

Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful…. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are.

Where the money comes from is as vague in Fitzgerald as it is in James, but he is very clear about what it does to character. As a middle-class, Middlewestern Irish Catholic, from what Edmund Wilson called “a semiexcluded background,” he was capable of double vision, the appearance of viewing character and scene almost simultaneously from the inside and the outside. Fitzgerald’s narrators always seem to be a part of the festivities even as they shiver outside with their noses pressed up against the glass. Listening to a tune from a piano across a Minnesota lake in “Winter Dreams,” Dexter Gordon thinks:

The tune the piano was playing at that moment had been gay and new five years before when Dexter was a sophomore at college. They had played it at a prom once when he could not afford the luxury of proms, and he had stood outside the gymnasium and listened. The sound of the tune precipitated in him a sort of ecstasy and it was with that ecstasy he viewed what happened to him now. It was a mood of intense appreciation, a sense that, for once, he was magnificently attune to life and that everything about him was radiating a brightness and a glamour he might never know again.

“I was within and without,” says the more jaded Nick Carraway, “simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.” For an all too brief period, Fitzgerald achieved control of this remarkable voice, which perfectly balanced sympathy and distance, passion and irony.

By the end of the Twenties, Fitzgerald became increasingly dependent on writing short fiction for money, a habit, like drinking, that he was always trying to break. The strain increasingly shows. The Basil Duke Lee series, written in the late Twenties, reach back into his childhood in an apparent attempt to recover the old ebullience. The best of them come alive with memories of childhood and adolescence, and Fitzgerald repeated the experiment, from the point of view of a girl, in his Josephine Perry stories. These stories were very successful with the Post and, like the contemporaneous “Last of the Belles” (Post, 1929), they remain readable today. These second string stories with their belles and balls and debutantes in fact seem more characteristic of his short fiction than his half dozen best.

Bruccoli includes the last of these, “Emotional Bankruptcy” (1931), in which Josephine lays waste to the Princeton prom and spends her favor where she pleases until in New York she meets a war hero in a blue French aviator’s uniform who answers all of her dreams of perfection, only to discover that she has no love left to spend. When finally she finds herself alone with this perfect man she kisses him and feels nothing. Desperately wanting to be swept away and conquered, she discovers that “all the old things are true. One cannot both spend and have. The love of her life had come by, and looking in her empty basket, she had found not a flower left for him—not one.”

Written at a time when he felt his confidence slipping away, and he was reaching back into his early youth in an attempt to recover a lost vitality, the story is one of the clearest expressions of Fitzgerald’s rather chaste idea that an individual is allotted a fixed amount of emotional capital to be husbanded or squandered. The premise of an eighteen-year-old girl attaining a state of emotional exhaustion after a few years of flirting and light necking will strike some readers as absurd. But capital is Fitzgerald’s metaphor for creation as well as for emotion. Although he never owned a single share of stock, financial metaphors were entirely natural to a writer so permeable to the spirit of his age.

In “The Bridal Party” (Post, 1930) and “Babylon Revisited” (Post, 1931) Fitzgerald was able, almost for the last time, to turn his emotional and financial difficulties into fiction which reverberated with the larger national crisis. “The Bridal Party” takes place on the eve of the stock market crash; a wealthy groom-to-be discovers he has lost everything. Offering his fiancée her freedom, which she declines, he recklessly proceeds with a spectacular Parisian wedding, which exhausts his remaining capital. The famous “Babylon Revisited,” in which Charlie Wales returns to a somber, sober, American-free Paris to try to regain custody of his daughter, is the literary equivalent of a hangover, a story filled with a terrible sense of fragility and loss. It contains some of Fitzgerald’s sharpest scenes and some of his most famous lines. The chronology is shaky; within the space of two early paragraphs Charlie somehow twice crosses the Seine from Right to Left Bank. But the story is strong enough to survive even the offstage melodramatic death of a wife who is locked out of the apartment by her husband, wanders the snow-covered streets, and catches pneumonia.

Thinking back on the world that has passed out of existence with the crash, Charlie remembers “thousand-franc notes given to an orchestra for playing a single number, hundred-franc notes tossed to a doorman for calling a cab.” And

the women and girls carried screaming with drink or drugs out of public places—

—The men who locked their wives out in the snow, because the snow of twenty-nine wasn’t real snow. If you didn’t want it to be snow, you just paid some money.

When the bartender at the Ritz says he heard Charlie lost a lot in the crash, Charlie replies that he did, adding, “but I lost everything I wanted in the boom.” Written shortly before “Emotional Bankruptcy,” “Babylon Revisited” employs the same metaphor to different, and far better, effect. Charlie Wales is recovering from a long debauch, but much has been irrevocably spent on the way. “He suddenly realized the meaning of the word ‘dissipate’—to dissipate into thin air; to make nothing out of something.”

It’s hard to avoid the feeling that Fitzgerald is speaking to us directly in lines like these; though Charlie’s story is related in the third person the narrative voice is that of his consciousness; the delicate balance Fitzgerald achieved earlier between sympathy and distance here tips toward Charlie’s own view of himself. An alcoholic, Charlie has since his hospitalization in Switzerland cultivated the habit of taking one drink a day, a medically unsound course of therapy which he insists on explaining to everyone. Charlie needs to convince his hostile sister-in-law, Marion Peters, that he is steady enough to reclaim his daughter from her guardianship, but his immediate hopes are destroyed when two of his old drinking buddies track him down to the Peters apartment and confirm her fears in one of Fitzgerald’s most painful scenes. Our sympathies, of course, lie entirely with Charlie.

Near the end of the story Fitzgerald unnecessarily goes out of his way to tell us, “He had not touched his drink at the Peters’, and now he ordered a whisky and soda.” Yet in spite of the lack of distance and other more obvious faults, this seems to me Fitzgerald’s most moving story. In “Babylon Revisited” Fitzgerald manages, almost heroically and sometimes shakily, to make Charlie Wales’s domestic tragedy stand for the guilty morning-after of his generation.

Increasingly Fitzgerald was writing not of fairy-tale courtships but of the marital strife which succeeded them. The recurring Fitzgerald plot of middle age is that of role-reversal between husband and wife—the emotional ascent of one partner intersecting the decline of the other—which we first encounter in “Head and Shoulders,” and which receives its fullest development in Tender Is the Night. In several of the stories wives slowly drain the vitality from their husbands or rise as the initially stronger male sinks, a zero-sum view of matrimonial partnerships that probably reflects the dynamics of the Fitzgerald household. “Two Wrongs” (Post, 1930) for example, is a rather schematic story of a successful theatrical producer, “a fresh-faced young Irishman exuding aggressiveness and self-confidence,” who marries an aspiring actress. He behaves badly for several years before settling down, chastened by the loss of his golden touch, and feeling “a vague dissatisfaction that he had grown to need her more than she needed him.” She trains for the ballet, her first great part coming on the eve of his discovery that his lungs are riddled with tuberculosis. They convince each other that she should take the part while he goes to Denver to recover, though it’s pretty clear he won’t.

“What a Handsome Pair!” (1932) baldly maps the intersecting arcs of a sporting couple who drift apart after the husband loses his patrimony on Wall Street, the wife becoming contemptuous of her husband as she becomes a celebrated amateur golfer, while he’s forced to give lessons to make ends meet. Their shared interest, which makes them seem such a perfect couple, causes them to compete for the same prizes, and drift apart. “People tried to make marriages coöperative and they’ve ended by becoming competitive,” the narrator says, far too neatly, toward the end.

Fitzgerald’s prose is often slack in these later stories—a woman is described, redundantly, as “full of a keen, brisk vitality.” With the minor exception of the famous “Crazy Sunday” (1932) the stories of the early Thirties, written as Fitzgerald tried to finish his fourth novel, lack the control of the earlier work, or the emotional engagement of “Babylon Revisited.” His capital, to use his own metaphor, has been stretched thin. Still, there are marvelous passages, many of which began in his notebooks and ended up later in the novel (see “One Trip Abroad,” [Post, 1930]).

Tender is the Night, Fitzgerald’s full-length treatment of marriage, contains some of his most beautiful prose, although economy and concision are not necessarily among its virtues, as they were in Gatsby. As in the men’s suits of the period there is generous drapery in the cut of the sentences, particularly in the first two sections, which show the layers of many years’ composition and revision. Rich in descriptions of the Mediterranean landscape, the prose is certainly his most sensuous:

Following a walk marked by an intangible mist of bloom that followed the white border stones she came to a space overlooking the sea where there were lanterns asleep in the fig trees and a big table and wicker chairs and a great market umbrella from Sienna, all gathered about an enormous pine, the biggest tree in the garden. She paused there a moment, looking absently at a growth of nasturtiums and iris tangled at its foot, as though sprung from a careless handful of seeds, listening to the plaints and accusations of some nursery squabble in the house. When this died away on the summer air, she walked on between kaleidoscopic peonies massed in pink clouds, black and brown tulips and fragile mauve stemmed roses, transparent like sugar flowers in a confectioner’s window—until, as if the scherzo of color could reach no further intensity, it broke off suddenly in mid-air, and most steps went down to a level five feet below.

There is a languor here different from the hyperkinetic, telegraphic description of Tom Buchanan’s garden on Long Island Sound, with its rolling, leaping lawn, which “started at the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarter of a mile, jumping over sun-dials and brick walks and burning gardens—finally when it reached the house drifting up the side in bright vines as though from the momentum of its run.” The bright primary colors of Gatsby, the “yellow cocktail music,” have been replaced by pastels. But if it lacks the noontime brightness and classical structure of Gatsby, Tender is the Night has a more oblique grandeur.

Fitzgerald’s last first-rate story, “Babylon Revisited,” was written in 1931. Six years before he died, in 1934, Fitzgerald wrote in his notebooks, “It grows harder to write because there’s much less weather than when I was a boy and practically no men and women.” Depressed over Zelda’s illness, bedeviled by alcohol and financial worries, he had increasing difficulty writing. With few exceptions, the stories of his last five years are mainly sketches, like the static “Afternoon of an Author” (1936), in which Fitzgerald describes the quotidian round of a physically and emotionally exhausted, washed-up writer. The men and women and weather being gone, what he had left was his own imagined failure, in which, scrupulously, he found no romance or drama.

Fitzgerald’s physical and spiritual exhaustion is described brilliantly, if obliquely, in the three essays he published in Esquire in 1936 (“The Crack-Up,” “Pasting it Together,” and “Handle with Care”). In wrenching himself free from the convention of fiction and the (for him) dead shell of the shapely, spritely story, Fitzgerald finally and ironically regained much of the old objectivity about his immediate experience which he had begun to lose so conspicuously around the time of “Babylon Revisited.” The man who had once dramatized himself as both Nick Carraway and Jay Gatsby in the same novel, having no more costumes in the closet, steps back and tells us with astonishing detachment about a failed dreamer named F. Scott Fitzgerald, comparing him to a cracked plate, “the kind that one wonders whether it is worth preserving.” One can easily imagine the histrionic possibilities here, and yet he scrupulously avoids the easy glamour of decay. “I wanted to put a lament into my record, without even the background of the Euganean Hills to give it color.” Fitzgerald is relentlessly, uncharacteristically prosaic. The essays are amazing for their candor—except for their central evasion. He describes a nervous breakdown of sorts, a sudden severe depression which robbed him of pleasure in the things of this world and nearly of the will to live. But he barely alludes to the alcoholism which had such a devastating effect on his later life.

Edmund Wilson reprinted these pieces in The Crack-Up in 1945. Something of a posthumous autobiography, the volume included the beautiful retrospective essay “My Lost City,” an elegy for the New York of the author’s youth, and the equally haunted and time-obsessed “Early Success,” as well as letters and entries from Fitzgerald’s notebooks. The notebooks are a catalog of raw materials for the stories: lists of popular songs and names, anecdotes and lines overheard, descriptions of landscape and character. One sees how the appearance of ease in the better stories was not lightly achieved. Fitzgerald was a social historian, faithfully recording the passing moments of his own times, down to the names of fleetingly popular dances—a meticulous realism practiced at the service of his own romantic impulse to arrest the passage of time.

Published the same year as the Viking Portable Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up helped to spark the revival of interest in Fitzgerald. Since then Fitzgerald has become both a myth and an industry. Yet it still seems necessary to celebrate the short stories, uneven in quality as they may be, and even to propose that “Absolution,” “The Rich Boy,” “Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” “Babylon Revisited,” and a few others, are among the best written by an American.

This Issue

August 15, 1991

-

1

In September of 1929, See Andrew Turnbull, Letters (Scribner’s, 1963), p. 307. ↩

-

2

In his scathing biography, Invented Lives: The Marriage of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald (Houghton Mifflin, 1984), James R. Mellow puts to bed, forever one hopes, the alleged exchange between Fitzgerald and Hemingway about the rich being different.—Stop, you’re both right! According to Maxwell Perkins, Hemingway was the recipient of the celebrated riposte, while Fitzgerald was nowhere in sight: “Hemingway and the literary critic Mary Colum had been lunching together when Hemingway made a passing remark about his wealthy acquaintance: I am getting to know the rich. And it was Mary Colum who made the famous rejoinder that the only difference between the rich and other people was that the rich had more money.” ↩