Federico García Lorca is one of the best-known poets of the twentieth century and one of the best-loved Spanish poets of any time, but he remains a curiously elusive figure, restless and changing in his work as in his life. Does he belong to tradition or to the avant-garde? Are his strengths his simplicity and closeness to the popular imagination, or his elegance, sophistication, and learning? Did the author of so many delicate children’s songs also create all those poems and drawings riddled with ugly sexual fear? Can the poet of the darkly tormented homoerotic sonnets really have produced the shrill railing against “fairies” that stains the “Ode to Walt Whitman”? Is there a way to get from the haggard drama of The House of Bernarda Alba to the Pirandellian high jinks of The Public?

The answer to all these questions is yes. The alternatives are not alternatives, they are Lorca. But that is another way of saying how elusive he is; and was to himself. An early poem speaks of an “uncertain heart”—este corazón mío ¡tan incierto! The phrase sounds like the expression of a youthful hesitation but it turns out to have been a prophecy, a preview of a long habit.

Lorca was born near Granada in 1898. His family was well-to-do and numerous, and his childhood seems to have been both sheltered and colorful. He was unathletic—in his biography of Lorca Ian Gibson remarks that “there is no record of anyone ever having seen Lorca run”—and none too keen on school: “docile and undisciplined,” as his brother later put it. But he was sociable and imaginative, and greatly gifted musically, becoming a friend and protégé of the composer de Falla. Lorca thought of Granada as an inward-looking place, a city living in its defeated past, but accounts of its artistic life make it sound fairly lively. After attending the university there Lorca moved to Madrid, where he met Buñuel, Dalí, and a spirited crowd of aesthetes and pranksters. Lorca wrote profusely from an early age, and acquired a considerable reputation as a poet and a playwright, but he was reluctant to publish books, and what he did publish scarcely represented his rapidly shifting interests. He was tired of his most famous volume, Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads), by the time it appeared in 1928; and his huge success as a playwright—at one point he had three plays on simultaneously in Madrid—made him want to rethink the theater. He traveled in North and South America to huge acclaim—he was a tremendous performer of poems, songs, lectures, and a fine pianist—but seems never to have been able to convert his fame into confidence. It is this brilliant uncertainty that makes his work seem both miraculous and uneven; troubled when it looks calm, oddly smooth and authoritative when it announces anguish.

Pablo Neruda’s ode to the poet (published in Residence on Earth II,1 1935) ends on a curiously enigmatic note: Ya sabes por ti mismo muchas cosas, / y otras irás sabiendo lentamente, “You know many things through yourself [on your own, or by your own experience], / and others you will be getting to know slowly.” Much of what Lorca might have got to know was withheld from him by his early death—he was assassinated by Nationalist thugs at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Neruda could not have foreseen that, but his lines do seem worrying as well as promising: as if Lorca already knew too much and too little, as if what he had yet to learn could only come hard, a ruination of what was not quite innocence. Of course Neruda may only have meant to celebrate the poet’s knowledge of the multifarious, brightly colored world, but even that world, in the poem, is chiefly a place of tears and goodbyes and emptiness, and Neruda’s very praise of Lorca’s vision swerves to bitterness: “Federico, / you see the world, the streets, / the vinegar….”

Collected Poems is a bilingual edition with a very good introduction and excellent notes by Christopher Maurer. It is actually Volume II of Lorca’s collected poems in English. Volume I, also edited by Maurer, was the bilingual Poet in New York, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988). The present volume includes in full all the other books of Lorca’s poetry, with the exception of the early Libro de Poemas, (Book of Poems), from which there is a selection. The translations in this volume are by Francisco Aragon, Catherine Brown, Will Kirkland, William Bryant Logan, David K. Loughran, Jerome Rothenberg, Greg Simon, Alan S. Trueblood, Elizabeth Umlas, John K. Walsh, Steven F. White, and Maurer himself; and as one might expect of the work of so many hands, the styles are quite varied. Most of the translators, as Maurer says, have shunned the “poetical.”

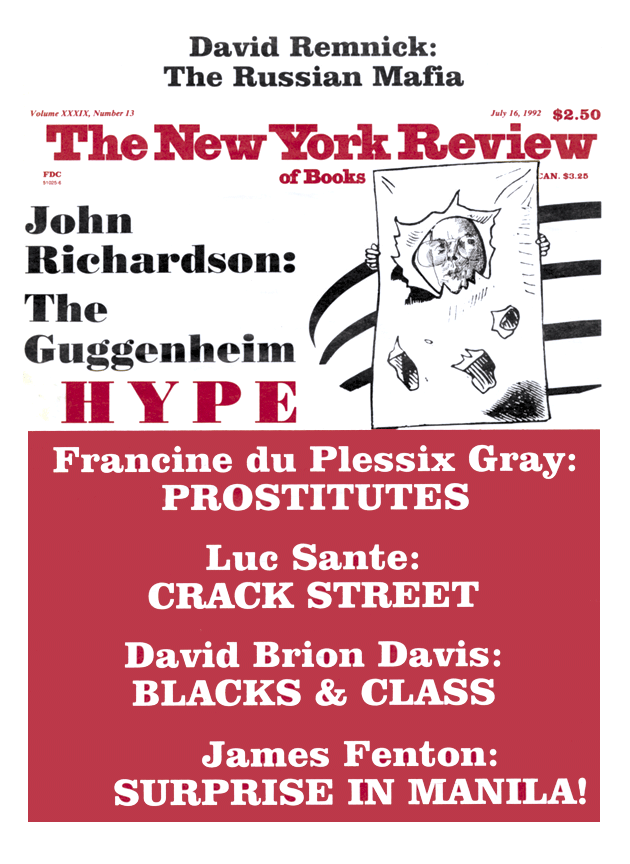

Advertisement

Overall the work is both ingenious and accurate, setting a very high standard for translation of verse from Spanish. Occasionally—a dozen times perhaps in this very large volume—the translators give in to the mysterious impulse to meddle rather than render. Dogs become mongrels, water becomes sea. Why would anyone want to make a music box on the wind, una caja de música / sobre la brisa, a “music box grinding away”? Or write “where poplars thrive” for among the poplars? “Headless and blind” where the Spanish has only headless? Or want to offer variation where Lorca plainly offers repetition? “Look” and “stare” for the repeated look; “fading,” “starved,” and “die” for a line that simply repeats die?

Children and childhood recur again and again in Lorca’s work. There is a sense of wanting to go back to a loved place and a time before torment, but even the place and the time are haunted; fragile, always invaded paradises. The poems make the very happiness of Lorca’s childhood seem streaked with anguish, and childhood becomes a metaphor for what even childhood cannot possess. Passion is “like a lost child / in a forgotten tale,” literally like an abandoned child in a story which has been erased: twice lost. When Lorca writes of the child “all the poets / have lost,” he means, I take it, both the Wordsworthian infant poets generally forget or betray and the particular child he himself was.

In one sense Lorca never abandoned his own childhood, and his weakest poems are those where he is trying hardest not to let go; where he gets only a childlike effect, or seeks too consciously to mime beliefs that are much simpler than his own. But in a deeper sense he never stopped looking for his childhood, and in that quest lies much of what is most powerful and most lyrical in his writing. A wonderful 1929 poem begins “Para buscar mi infancia, ¡Dios mio!” “To look for my childhood, my God!” and ends by seeing childhood as a rat fleeing through a dark garden. Another poem of the same year evokes the poet’s “eyes of 1910”: Aquellos ojos mios de mìl novecíentos diez, and describes what those eyes did and did not see: a vision of loss, dust, and disguise. A slightly earlier poem sees a lover’s childhood as a world of fable gone beyond all recall, leaving only its magical memory, and the (marvelously phrased) índíces y señales del acaso, “traces and signs of what might be,” literally the marks and signs of the maybe.

Childhood represents what can be damaged or abolished, but it also evokes possibilities, all too often cancelled possibilities. “My garden,” Lorca said in a letter, “is the garden of possibilities, the garden of what is not, but could (and at times) should have been, the garden of theories that passed invisibly by and children who have not been born.” The heroine of the play Yerma longs for the baby she cannot have, while Adam, in a famous sonnet, dreams not of his posterity but of his barrenness, his role as first and last man, his children a mere vision of what is not, a burned-out possibility, neutra luna de piedra sin semilla / donde el niño de luz se irá quemando, “a neuter moon of seedless stone / where the child of light will burn.”

In a remarkable letter, written when he was twenty-three, Lorca says, with a touch of whimsy and a good deal of anxiety, that he hasn’t been born yet:

The other day I was meditating upon my past… and none of the dead hours belonged to me. It wasn’t I who had lived them…. There were a thousand Federico García Lorcas, stretched out eternally in the attic of time. And in the storehouse of the future I beheld another thousand, all nicely pressed and folded and piled one on top of the other, waiting to be filled with helium and fly aimlessly away…. I live on borrowed things, what I have inside me isn’t mine, and we’ll see if I am born.

Lorca did wonders with his borrowed things, but when was he not borrowing? Critically, the question about what he knew and did not know becomes a question of how knowing the poems are: a question of tone or pitch rather than information, or if you prefer, of the quality of Lorca’s imitations of innocence, and of his success in keeping knowledge at bay. So much of his work skirts a tourist Andalusia, all flamenco and fans and moonlight, and it is often acclaimed for just that reason. Christopher Maurer in his introduction to the Collected Poems sees a note of parody in much of Lorca’s writing in this gypsy or folkloric vein, a hint of “the emotionally overwrought style of the cante jondo.” Sometimes the poems seem not to parody but simply to pastiche the flamenco world, to offer a slender and elegant reprise of its favorite numbers. But often Lorca manages something altogether more startling: the effect of an original folk song, as if he had managed to disappear into the voice of a culture. At such moments what counts is the poet’s stylistic discretion, his ability to let motifs speak for themselves. Saber callar a tíempo, knowing when to be silent, is how a distinguished scholar described the art of the traditional Spanish ballad, and Lorca’s mastery of this art is nowhere better seen than in the well-known “Memento”:

Advertisement

Cuando yo me muera,

enterradme con mi guitarra

bajo la arena.Cuando yo me muera,

entre los naranjos

y la hierbabuena.Cuando yo me muera,

enterradme, si queréis,

en una veleta.¡Cuando yo me muera!

When I die,

bury me with my guitar

beneath the sand.When I die,

among orange trees

and mint.When I die,

bury me in a weathervane,

if you wish.When I die!

The poem manages to seem surprised at its own refrain, as if death, however familiar as an idea, were incredible as a fact; a graceful traditional theme turns into an actual threat. The Spanish gets very delicate results through the mood of the verb, a quite ordinary usage which requires that future events following the word “when” take a subjunctive, suggesting the chance that such things might not happen; and through the courtesy of “if you wish,” which means both “if you want to,” and “if you would be so kind.”

We see the same effect in this song:

Córdoba.

Lejana y sola.Jaca negra, luna grande,

y aceitunas en mi alforja.

Aunque sepa los caminos

yo nunca llegaré a Córdoba.Córdoba.

Distant and lonely.Black pony, large moon,

in my saddlebag olives.

Well as I know the roads,

I shall never reach Córdoba.

And in the Gypsy Ballads:

La luna vino a la fragua

con su polisón de nardos.

El niño la mira, mira.

El niño la está mirando….Por el olivar venían,

Bronce y sueño, los gitanos.

Las cabezas levantadas.

y los ojos entornados.The moon came into the forge

in her bustle of flowering nard.

The little boy stares at her, stares.

The boy is staring hard….Through the olive grove

come the gypsies, dream and bronze,

their heads held high,

their hooded eyes.

Well, the gypsies of dream and bronze perhaps belong to an eye which is not a gypsy’s, and the effect of a slight distance is perhaps even more common in Lorca than the effect of speaking for a culture. In spite of Lorca’s great facility, these are often very considered poems, precisely poised between mannerism and sentimentality.

En la mitad del barranco

las navajas de Albacete,

bellas de sangre contraria,

relucen como los peces.

Una dura luz de naipe

recorta en el agrio verde

caballos enfurecidos

y perfiles de jinetes.Halfway down the steep ravine

blades from Albacete,

lovely with the other’s blood,

are glistening like fish.

Against the bitter green,

a card-hard light

traces raging horses

and riders’ silhouettes.

This has all the elements of a gypsy fight out of Mérimée, but the coolness of the voice, its interest in the beauty of the bloody knives, and its characterization of the light as like a playing card—the very implication of hardness found in playing cards—turns the whole scene into a highly stylized engraving. It has the tension of flamenco itself when it seems not overwrought or dripping with emotion but on the contrary drastically contained and formal, full of desperate implication.

Lorca himself associated this kind of terseness or precision with Spain. “Spain,” he said, “is the country of profiles…. Everything is drawn and delimited in the most exact way.” We get a similar sense when Lorca describes un horizonte de perros, “a horizon of dogs,” barking in the distance. The dogs belong to the world of the folk song, but the vision is that of a modern draftsman.

The following shows the risk of this effect, I think, how easily it might (but doesn’t here) topple into winsomeness, a winking at the reader across the apparent simplicity of the line:

El día se va despacio,

la tarde colgada a un hombro,

dando una larga torera

sobre el mar y los arroyos.The day moves slowly away,

over the creeks and the sea,

the afternoon draped from its shoulder

like a torero, his back to the bull.

For instances of the risk not coming off we might think of La tarde está / arrepentida, / porque sueña / con el mediodía, “The evening is / penitent, / still dreaming about / noon. Or: La iglesia gruñe a lo lejos / como un oso panza arriba, “The church growls in the distance / like a bear turned on its back.”

But Lorca has other voices too. That of the formal lament, for example, or the classical sonnet; or the excited and anguished free verse of Poet in New York. And we tend to forget how light and funny he can be, as in the Suites. “If the alphabet should die,” one poem says, “then everything would die…. The whole of life / dependent on / four letters.” We look at you through a magnifying glass, the poet says to Venus: “the renaissance and me.” Newton’s apple falls on his nose, and the great man “scratches / his Saxon nostrils.”

Among the later verse, some of the most subtle appears in the Diván del Tamarit (The Divan at Tamarit), a graceful homage to Moorish Spain. Here are simple singing lines, an appearance of peace; and all Lorca’s tortured themes, desperate love, dead children, absence, bitterness, sorrow, murmuring just beneath the surface, or even at the surface:

Siempre, siempre: jardín de mi agonía,

tu cuerpo fugitivo para siempre,

la sangre de tus venas en mi boca,

tu boca ya sin luz para mi muerte.Ever, ever, my agony’s garden,

your elusive form forever:

blood of your veins in my mouth,

your mouth now lightless for my death.

… He cerrado mi balcón

porque no quiero oír el llanto,

pero por detrás de los grises muros

no se oye otra cosa que el llanto.Hay muy pocos ángeles que canten,

hay muy pocos perros que ladren,

mil violines caben en la palma de mi mano.Pero el llanto es un perro inmenso,

el llanto es un ángel inmenso,

el llanto es un violín inmenso,

las lágrimas amordazan al viento,

y no se oye otra cosa que el llanto.I have closed off my balcony,

for I do not want to hear the weeping,

But out there, beyond gray walls,

nothing is heard but the weeping.There are very few angels who sing.

There are very few dogs who bark.

A thousand violins fit in the palm of my hand.But the weeping is an enormous dog,

the weeping is an enormous angel,

the weeping is an enormous violin,

tears have muzzled the wind,

and nothing is heard but the weeping.

The Tamarit poems and some others appear in Edwin Honig’s volume. The translations are rather more hit-and-miss than in the Collected Poems, but there are some fine moments—“you were snow, stirring my heart”—and Honig does a better job on the difficult “Dialogue of Amargo,” where a traveler on the way to Granada, accepting a ride and the gift of a knife, appears to accept his death, and to know he accepts it. But in the context of Lorca’s work in English translation, the most interesting feature of this book is its containing four puppet plays, and the intriguing Play Without a Title, to which I shall return.

Lorca’s puppet plays appear early and late in his career, and are literally written for performance by hand-held puppets. One notable performance took place in the Lorca family house in 1923, with Lorca working the puppet Don Cristóbal, and de Falla providing the music, which included the first Spanish performance of (part of) Stravinsky’s Histoire du Soldat. Lorca performed a version of Don Cristóbal’s Puppet Show in Buenos Aires in 1934, with a new preface written for the occasion, in which the chief puppet recalls his earlier association with the poet. Don Cristóbal is said to be “the mainstay of the theatre”—“All theatre starts with you”—and also to be Falstaff’s father. There is a popular Spanish puppet tradition going back to the time of Cervantes—Don Quixote notably interrupts a puppet show—but the avant-garde had also taken it up during the twentieth century.

Lorca’s puppet plays are lyrical and mocking. Their plots concern marriage and romance and the discomfiture of villains. They show Lorca at his most lighthearted and charming, but also at his most discreetly experimental, able to get delicate emotions out of the mockery of emotion. Stage directions instruct characters to cry “comically” or “in perfect rhythm.” The theater knows it is theater—“everything takes on an intensely theatrical bluish tinge”—and catches real feelings by refusing to simulate them. “O what a burden it is,” the puppet says, “to love you as I love you!” We sense the burden because the puppet cannot, because there is no actor between us and the metaphor, and we are moved by the cliché rather than in spite of it. There is a similar moment in another mood when the bullying Don Cristóbal, seemingly a Spanish version of Punch and Judy rolled into one, is said to be “so brutal that even his shadow tears things to bits.” I know people like that.

Line of Light and Shadow is a thematic exploration and catalogue raisonné of Lorca’s drawings, 381 items, all reproduced on a small scale, many in their original size. The drawings are scrupulously related to relevant poems, situated in Lorca’s life and among his influences. Mario Hernández thinks Lorca learned to work with his limitations as a graphic artist, and this must be true; but a certain false naiveté remains in this work, precisely the quality the poems flirt with but often manage to exchange for something more austere.

It is not, I think, the trembling line that makes the drawings interesting, as Lorca himself seems to have thought; it is the frankness with which they picture his obsessions. Among all the gypsies and sailors and clowns and saints, full of the fragile charm of a shaky Picasso, are works of real horror, profoundly disturbing representations of the artist’s encounter with disgust and fear. “Venus,” for example, drawn in Buenos Aires in 1934, represents a version of the armless Venus de Milo, the words “Love” and “Moon” apparently trickling from her mouth, while a fountain of (apparently) blood and tiny hands gushes from her vagina. The words “sexual water” are typed above the woman’s round, schematic breasts—this is the title of the poem by Neruda that Lorca meant the drawing to illustrate, although the fluids in Neruda drop rather than sprout. There is awe here, I take it, even a sort of admiration for the fertile but unmotherly goddess; but the swarming hands seem inescapable, and the blood at the center of the picture makes violent demands, but what demands?

We should perhaps associate this drawing with the play Yerma, also completed in 1934, in which a childless woman throttles her sterile husband, describing her act as the killing of her son. The implication is that this harsh husband is the only child she will ever have, and also that in killing him she is killing her own longing, as if she had had a child and stifled it; or were killing all the children she could ever have. She, like Venus, is fertile and murderous; but the play, unlike the drawing, appears to endorse desire rather than horror.

The slightly earlier “Sexual Forest” shows a pattern of dark vertical squiggles, rather like newts, life forms of some sort perhaps, or abstract trees. The creatures all appear to be urinating. Among them are disembodied mouths, some vomiting. Helen Oppenheimer2 associates this drawing with the Paisaje de la multitud que orina, “Landscape of a Pissing Multitude,” in Poet in New York, and certainly the poem has the same mood of murky sexual adventure, all night and trees and ambush and risk. The picture communicates more energy, though, and more whispering secrecy.

Most troubling of all is “Death of Saint Rodegunda,” 1929, where a monstrous saint, a drooping cartoon-like figure, appears to be vomiting and menstruating at the same time. She is half-lying on what looks like an operating table, she has wounds in her chest, and she has two heads and two sets of eyes, as if she were watching herself suffer, or as if she had become her own terrifying ghost. Maurer says cautiously that “Lorca’s interest in this sixth-century saint, Queen of the Franks, to whom he gives a martyrdom of his own invention, has never been satisfactorily explained,” but perhaps it isn’t an explanation we are looking for. Saint Rodegunda looks like an icon of sought-out erotic martyrdom, a surrender to the very fears the other pictures present, with death as a desperate reward.

The drawing itself (or a drawing of the death of Saint Rodegunda) appears in Lorca’s filmscript “Trip to the Moon,” just after a double exposure of a camera movement up and down a set of stairs, and just before a woman in mourning falls down the stairs. There is vomiting in the filmscript, too, and it ends with a series of mocking clichés about love and death. Earlier in the film the words Help Help Help appear “moving up and down above a woman’s genitals.” This seems to take us back to the Venus drawing, and some kind of panic about the origins of life. I don’t profess to understand this, but the material certainly clusters significantly together.

Similar themes occur in more mastered form in the first of the so-called “Sonnets of Dark Love,” with its plea for blood and suffering, and its relish of wounds.

Pero ¡pronto!, que unidos, enlazados,

boca rota de amor y alma mordida,

el tiempo nos encuentre destrozados.But hurry, so together, inter- twined,

mouths bruised [literally, broken]

with love and souls bitten,

time will find us wasted [literally,

destroyed].

These eleven sonnets were written in 1935, but “many” of them, Maurer says with uncharacteristic vagueness, “remained unpublished in Spanish until December 1983.” The sonnets were then published in an anonymous limited edition, followed, in 1984, by a version authorized by the poet’s family. They appear in Collected Poems, and also in a very good new version by Merryn Williams, in her Federico García Lorca: Selected Poems (Newcastle: Bloodaxe Books, 1992). The poems are explicit about their unhappy passion, and the gender of a past participle in one of them makes clear that the lover is male. Perhaps that was enough to keep Spanish publishers quiet for so long.

The sequence is called “Sonnets of Dark Love” because the poet Vicente Aleixandre remembered Lorca’s using the title at a reading a few months before his death—and also, we might say, because the phrase itself occurs twice in the poems. Ian Gibson is skeptical of Aleixandre’s claim that the darkness has to do with love’s torment and not specifically with homosexual love; and certainly darkness in the poems appears to involve deviance and denial, as well as sorrow.

But the sequence, although still anguished and devoted to the mixing of religious and erotic images, seems after the first poem to portray a passion which is more resolved, less guilt-entangled, certain of its direction if not of its object. A sonnet in the manner of Góngora ends

Así mi corazón de noche y día

preso en la cárcel del amor oscura

llora sin verte su melancolía.This is how my heart, night and day,

locked in the dark prison of love,

cries with melancholy, deprived of your sight.

(Walsh/Aragon in Collected Poems)Thus my heart by night and day

sealed in the prison of dark love,

weeps and grieves while you’re away.

(Williams, in Selected Poems)

Only the “dark love” hints at something other than absence, and the following poem, “Ay voz secreta del amor oscuro,” “O secret voice of dark love,” finally, bravely says what I take it the drawings are unable to say, about homosexual or any other kind of sexual desire: “I am love, I am nature.”

This is of course the cry of the passionate Adela in Lorca’s equally dark House of Bernarda Alba. This play remains for many the essential Lorca. It was written in the last months of his life, and portrays the stark tyranny of the old order in Spain. The matriarch Bernarda Alba buries her husband and rules over her house and five daughters with iron indifference to all emotions and needs. The girls are hysterical and frustrated, and Adela, the youngest, manages to have a relationship with the almost mythical male Pepe el Romano. The play ends in violence and death. There is certainly a political climate here, but liberty is claimed and lost, driven to suicide, in the name of sexual feeling, and what is noteworthy about Bernarda’s oppression of her daughters is the arbitrariness of it. As Paul Julian Smith says in his subtle chapter on Lorca and Foucault in The Body Hispanic (Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press, 1989), Bernarda Alba’s power is without origin and apparently without end. And without plausible social motive. She doesn’t care about her neighbors or the values she upholds, she cares only about herself upholding them, cares about order because it is her order. It is as if the superego itself had been turned into an object of worship; the very mode of repression which makes Venus so alluring and alarming.

The recent television production of the play, shown on PBS and on Channel 4 in the UK, was a well-adapted film of a stage version directed by Nuria Espert and Stuart Burge. Glenda Jackson was appropriately snarling as Bernarda, and Joan Plowright splendidly rebellious and conniving as Bernarda’s canny housekeeper. The production didn’t quite catch the claustrophobic horror that prevailed in Mario Camus’s film version (1987), which was literally haunted by the shape of the unreachable Pepe el Romano, the man the girls dream of, and which was full of the prying, spying effect a camera gets so well, and discreetly punctuated by flamenco singing and stamping, the hoarse, shaken voice and rhythm of disaster.

Lorca said he was interested in a documentary effect in The House of Bernarda Alba—“these three acts are intended to be a photographic documentary”—but he probably meant this as a metaphor rather than a literal ambition. His brother, Francisco García Lorca, suggests that a photograph in this context would be like an engraving, an image Lorca also uses to describe scenes in his plays: close to reality but also stylized, like a wedding group.3 But the play is not so much stylized as lyrical about its darkness, and is marked by a number of self-consciously literary lines, so that the characters suddenly seem to realize that they are not only in a play but in an Important Play (“I shall put on the crown of thorns of those who are loved by a married man”). Lorca himself said there was “no literature” in the play, “not a drop of poetry”; and we can agree that for a literary and poetic play it’s pretty sober. But it is a play which very much needs the theatrical illusions it fosters, and it is all the more interesting therefore to know that Lorca was working at the same time on his Play Without a Title, which in its experimental shape and overtly theatrical content looks back to The Public, written in 1929–1930, but first published in 1976, and not performed in Spain until 1987. Play is included in the Honig volume, and both works are available in a translation by Carlos Bauer (New Directions, 1983).

It is customary to think of Lorca’s chief theatrical alternative to the lyric naturalism of Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba as the rather prettified surrealism of Once Five Years Pass (1931), a play dedicated, as Francisco García Lorca says, to “the emotion of time” but also muddled, I think, by all the things it finds it can’t say. The Public and Play Without a Title are different matters entirely. These plays are closer to Brecht than to surrealism, and ask what happens when an illusion, theatrical or otherwise, meets the sort of reality it is designed to deny, or meets a stronger illusion.

The Public has horses as well as humans for its characters, mythological figures as well as contemporary ones. It celebrates and agonizes over male homosexuality, and dreams of a theater which would reach the unmasked, incontrovertible truth. The play is set in a theater, and its plot, insofar as it has one, concerns the putting on of a play and the various ways a public can behave or be imagined to behave. At the end, in what seems to be a tragically despairing resolution, a conjuror coolly takes over from the defeated theater director. The idea of an open air theater gives way to “the true theater,” the theater beneath the sand. Even this, though, isn’t the liberated truth the characters long for; only the sort of truth you find under the sand. Love and truth are increasingly equated as the play goes on, but equated as impossible or at best ambiguous. There is a riot at a performance of Romeo and Juliet because the spectators have seen that the lovers (the actors, the characters) really care for each other. On the contrary, someone else says, the spectators are outraged because the lovers clearly don’t care for each other, they cannot love. It is horrible, another character says, to get lost in a theater and not to be able to find the way out. But how could theater save us from theater?

The Public doesn’t get us out of this labyrinth, but it does suggest that illusion and truth may both be processes, fictions we make real (or not), and that such practices, on stage and off, are what theater helps us to examine.

Play Without a Title is much shorter, and does not explicitly address so many tangled themes. But it does pursue the question of the possibility of love and truth, and the role of theatrical illusion in our understanding of the world. A group of actors is rehearsing A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the rehearsal merges with a performance, the spectators comment and get agitated, there is a riot involving shooting and aerial bombardment, and the play ends with the theater in flames. There is a truth in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one of the characters says, but it is a “terrible…destructive truth,” the truth of arbitrary magic, suggesting that “love…is an accident [una casualidad] and has nothing to do with us at all.” The theater might show us this truth, and then lend us an illusion to deal with it. But can the old theater do this? Or the new one? We don’t get an answer in this play, either, unless the riot is an answer.

The poet asks, Lorca wrote, not for benevolence but for attention. Attention to the work is the implication, but an interesting ambiguity lingers. Children, too, ask for attention. As a person Lorca seems to have needed more attention than most, and his art was one way of getting it. He told his fellow poet León Felipe that he wrote “so that people will love me.” But his work itself is not attention-seeking, or only attention-seeking. At its best it doesn’t clamor or demonstrate, it frames and explores. Its subject is not Lorca’s own moods or even ours, but the complex construction of feeling, the content and context of our love or our fear or our grief. There is an austerity even in Lorca’s fireworks, and his baroque lament for a dead bull-fighter ends with the unadorned asperity of absence, the abandonment of this and all bodies to the common anonymity of death, evoked in a pile of perros apagados, literally extinguished dogs, as if they (and we) were casually snuffed out like lights.

I think, too, of an exchange in Yerma, where her friend María says she is saddened by the heroine’s envy. “What I have is not envy,” Yerma says. “It is poverty.” Yerma’s poverty is that of the childless woman in a fertile rural world. She is not barren but uncherished, the Venus of Lorca’s drawing seen as an image of tragic lack. Perhaps her husband is afraid of her very desire, her immense appetite for the possible. Yerma does not want what others have, she only, fiercely wants what she herself needs: the child who would not be mere absence or hope, the child that all poets lose.

This Issue

July 16, 1992