A Virgin Mary earnestly spanking her son is hard to imagine and theologically absurd, somewhat like Santa Claus engaging in child abuse, or Uncle Sam desecrating the flag. Since Jesus cannot have misbehaved, and Mary cannot chastise unjustly, a picture of the subject, especially one over-life-size, pretending to real presence, is intrinsically impossible. And if we find such a picture in the current Max Ernst exhibition at MOMA,1 then we are either hallucinating or thinking heresy and consenting to blasphemy, whereas we should be alerting the Holy Office and the police.

The duplicity of Ernst’s picture encourages no such simple reflex. For one thing, the kind of domestic disturbance Ernst has invented ought to proceed in the intimacy of the home, indoors, as in Dutch genre painting. The boy’s imputed delinquency should be corrected in private. Yet this immense, glassy-eyed giantess sits like a monument between free-standing walls under an open sky, straddling a public space. And she sits (quite like Michelangelo’s Medici Madonna) on an upright block placed on a plinth. Could it be that we are shown not a woman but an effigy in weird animation, a statue forgetting itself because it thinks there is no one to see? Hardly. Since 1926, when this outrage first broke on a scandalized public, the ontological status of the punishing mother has never been questioned.

So then it’s the holy Virgin herself caught in a hitherto unpublicized moment. With her naked boy (who seems to be about five years old) sprawled on her lap, she flails at his blushing buttocks, while his halo rolls free, and the painter signs its diameter. Hallowed be his name.

The “Max Ernst” signature inside Christ’s aureole could be a clue, a hint of the artist’s self-involvement in the whole enterprise. Accordingly—though the subject, Ernst said, had been proposed to him by André Breton—recent writers on the picture have chosen the psychoanalytic approach, hoping to discover the motive for it among the artist’s own primal traumas and Oedipal fantasies. One studies the artist’s biography, his notebooks, his confessional doodles—anything that will permit one to disregard the picture itself and, as we shall see, one’s insinuated complicity in it.

Who, in fact, is watching the action? The title tells us, but in a way that seems slyly misleading. Ernst called the picture The Blessed Virgin Chastising the Child Jesus Before Three Witnesses: A.B. [André Breton], P.E. [Paul Eluard], and the Artist. On this cue, being summoned as witnesses, the three men behind the rear wall should be paying attention. So the 1986 catalog of the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, which owns the painting, speaks of “the witnesses to this unholy act, who look in on the foreground scene through a rear window.”2 A distinguished historian has them obligingly “looking through the window at an unusual scene”3—as befits the role assigned to them by the title. But that’s clearly wrong, and the catalog to the present show (the relevant passage written by Walter Hopps. p. 158) takes a long step in the direction of accuracy by setting the artist apart: “Of the three, only the gaze of Ernst focuses directly on the event transpiring.” But is it the foreground event that the keen-eyed painter is looking at? Try again.

A square aperture in the rear wall reveals the three “witness” faces, foremost the profiles of Breton and Eluard. And they, unlike you and me, ignore the spectacle with surreal disdain, spurning the privilege to which the picture’s title entitles them. The startling contrast between their indifference and our gawking is what defines us. How you and I, away from the picture, actually feel about it is irrelevant, because extraneous to the encounter. The point is that the depicted “witnesses” display a coolness which we, as we stand there and stare, and by virtue of staring, are rendered incapable of. The very attention we bring to the scene is shamed into prurience by the proffered alternative, the insouciance of the two poets.

Behind them looms the full face of the painter—too remotely recessed and too oddly angled by the obliquity of the wall to see what he knows us to be seeing. From his distant vantage, the window contracts to a slot, and the divine comedy in the foreground, for want of a periscope, is out of his sight. Yet his eyes are wide open and their fixed glance is on us, on me, measuring my reaction. This is a test.

The painting is engineered to embarrass: so long as I look, I am exposed to the artist’s accusing gaze as he watches the churl in me trapped in the act of ogling a sacrilege—a provocation which my betters scorn to acknowledge.

It’s a cruel jest and a no-win situation all around—for Jesus, his mater, and us voyeurs. Unless we fly to aestheticism to restore self-respect. Though the draftsmanship seems a bit lax here and there, it’s not a bad painting.

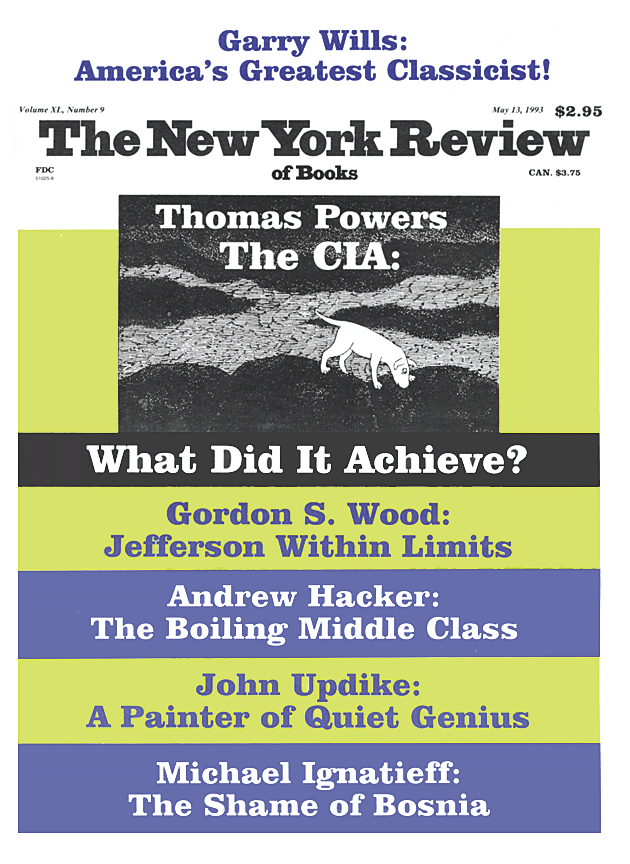

Advertisement

This Issue

May 13, 1993

-

1

The painting, 196 × 130 cm (77 3/16 × 51 3/16 in.), lent by the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, provides the climactic big bang to the exhibition “Max Ernst: Dada and the Dawn of Surrealism” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 14–May 2; The Menil Collection, Houston, May 28–August 29; The Art Institute of Chicago, September 15–November 30, 1993. Exhibition and catalog are the work of the Menil Collection. ↩

-

2

Evelyn Weiss, in Museum Ludwig Köln: Bestandskatalog (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1986), p. 68. ↩

-

3

Caroline Walker Bynum, “The Body of Christ in the Later Middle Ages” (1986), in her collection Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (Zone Books, 1992), p. 79. ↩