In response to:

Women Versus the Biologists from the April 7, 1994 issue

To the Editors:

Whether or not women are “superior” to men, is never a topic that I have found particularly meaningful. Hence, I was dismayed to read in an article by Richard Lewontin [NYR, April 7] that “The feminist anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy thinks women are superior because they are naturally more crafty and acquisitive than men, and have been made so by evolution.” I certainly don’t think this, and more importantly don’t understand how any fair-minded scholar could come to that conclusion based on anything that I have written.

In my 1981 book The Woman that Never Evolved, I noted that “widespread stereotypes devaluing the capacities and importance of women have not improved either their lot or that of human societies. But there is also little to be gained from countermyths that emphasize woman’s natural innocence from lust for power, her cooperativeness and solidarity with other women…” (p. 190). I wrote this because I believed that competition between females for direct access to resources or to access to particular males who controlled resources, was a more important selective force in primate evolution than had been recognized up to that point. This may be what Mr. Lewontin is referring to when he claims I think females are naturally “acquisitive.” In 1974, I was the first to propose that female primates may mate with multiple males so as to confuse information available to males about paternity and thereby enhance the survival of subsequent offspring, since former consorts might be more disposed to help, or at least not to harm, possibly related offspring. This has been a controversial and influential idea, and perhaps this is why Mr. Lewontin attributed to me the notion that females are naturally “crafty” (though he omits the critical context for the emergence of that craftiness, namely a world where females are trying to hold their own in a system otherwise favoring male interests). Nevertheless, “crafty” and “acquisitive” are his words, not mine, and none of this has ever led me to conclude that females were “superior” (or inferior) to males. Rather, what I have written is that “sociobiology, if read as a prescription for life rather than a description of the way some creatures behave, makes it seem bad luck to be born either sex…”

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy

Professor of Anthropology

University of California

Davis, California

To the Editors:

Richard Lewontin apparently spent so much time reading Ruth Hubbard’s books that he’s missed many recent papers about sex-differences in brain size and about the relation between brain size and human cognitive abilities. Perhaps he was referring to himself when he stated (p. 33) “As scientists grow older, they often give up research in favor of philosophy, history, politics…. Scientific work creates that bank account of legitimacy which we can then spend on our political and humanist pursuits.” He must be aware, however, that an overdrawn account can lead to bankruptcy.

Regardless, his claims (p. 34) that women’s brains are proportionately larger than men’s and that “no one has ever found a correlation between brain size and human cognitive abilities” are patently false. I recently published an analysis of autopsy data (in the 1992 issue of Intelligence) from 1,261 adults and showed, unequivocally, that after statistically controlling for differences in body size, men’s brains average about 100 grams (8 percent) heavier than those of women. At my suggestion, Professor Philippe Rushton analyzed data from a stratified random sample of 6,325 US Army personnel and showed that after controlling for effects of age, stature, and body weight, the cranial capacity of men averaged 110 cm3 larger than that of women. (This too was published in the 1992 issue of Intelligence.) Subsequently, Professor Nancy Andreasen used magnetic resonance imaging techniques that, in effect, create a 3-dimensional model of the brain in vivo, and found a similar sex-difference in brain size.

Since the turn of the century, numerous studies have shown that there is a positive correlation (+0.2) between various measures of head size and mental test scores in general intelligence as well as in spatial and reasoning ability. Recently, several independent studies used magnetic resonance imaging to estimate brain volume in normal people and found an even higher positive correlation between brain volume and cognitive abilities (+0.4, as reported by Professor Andreasen and her colleagues in the 1993 issue of American Journal of Psychiatry). The brain-size/intelligence relation has been found independently in both men and women.

Women have proportionately smaller brains than do men, but apparently have the same general intelligence test scores. Thus, I have proposed that the sex difference in brain size relates to those intellectual abilities at which men excel. Women excel in verbal ability, perceptual speed, and motor coordination within personal space: men do better on various spatial tests and on tests of mathematical reasoning. It may require more brain tissue to process spatial information. Just as increasing word processing power in a computer may require extra capacity, increasing 3-dimensional processing, as in graphics, requires a major jump in capacity. In support of this hypothesis is the published observation (by Andreasen) that brain size correlates most highly with performance tests in men and with verbal tests in women.

Advertisement

Predictably, correlations between cognitive abilities and overall brain size will be modest. First, much of the brain is not involved in producing what we call intelligence: variation in size/mass of that tissue will reduce the correlation. Second, mental test scores, of course, are not a perfect measure of intelligence and thus, variation in such scores is not a perfect measure of variation in intelligence. I suspect, however, that not even Professor Lewontin would deny that human intelligence is directly related to brain function (I am unaware of evidence suggesting that intelligence is derived, for example, from the liver). The evidence is clear that human brain size is a measure, albeit imperfect, of brain function. Richard Lewontin, Ruth Hubbard, and others with “politically correct” agendas, can ignore or even deny the existence of these fascinating aspects of human biology and behavior. They cannot, however, make them disappear.

C. Davison Ankney

Professor of Zoology

University of Western Ontario

London, Ontario, Canada

R.C Lewontin replies:

Sarah Hrdy’s direct complaint against me is just. Nowhere has she ever written that women are superior to men. Rather her point is that evolution by natural selection has made women who are “assertive, sexually active, or highly competitive, who adroitly manipulated male consorts, or who were as strongly motivated to gain high social status as they were to hold and carry babies” (The Woman That Never Evolved, p. 14). That is, women have been made by evolution into creatures that give them both equality with men in some ways and means of dominance over them (by “adroit manipulation”) in others. Like other sociobiologists, she believes that human nature must be understood as having been molded effectively by natural selection to maximize the passage of genes, but she is concerned to correct what she sees as a sexist bias in most sociobiology that sees the operation of this natural selection as only on males. To be fair to her, she is also more circumspect than most of her sociobiological colleagues about how strong the evidence is for the story about natural selection and the hegemony of the genes in human affairs. Nevertheless, she obviously believes in the story enough to have written a book and a number of popular articles on the matter, based on the comparison between humans and apes. Moreover, while usually being careful to say that human beings are very flexible and therefore are not just like other animals, she sometimes slips back into a more simplistic sociobiological mode, as when she writes that in “species after species…primate males have been able to…translate superior fighting ability into political preeminence over the seemingly weaker and less competitive sex” (The Woman That Never Evolved, p. 16). Chimpanzee politics?

It must be said, however, that no sociobiologist has ever claimed that men are superior to women, tout court. The claim has been, rather, that men have built into them certain properties that give them contextual superiority over women in the same sense that a watch that keeps correct time is said to be superior to one that loses minutes and hours. It is not abstract or moral, but functional superiority that is at issue. Evolution has made men better able to do some things than women, and those are the things that make the world go round. Hrdy sees a balance of forces between the sexes, rather than an unconditional superiority of men, like the system of checks and balances in the United States Constitution. (I am indebted to Ruth Hubbard for pointing out this parallel.) Men threaten and women manipulate.

The innocent reader may be somewhat surprised by the snotty ad hominem tone of C. Davison Ankney’s letter, a tone usually employed by injured authors whose books have been savaged in The New York Review. The mystery is solved by the revelation in Ankney’s letter that “At my [Ankney’s] suggestion, Professor Philippe Rushton analyzed data from a stratified random sample of 6,325 US Army personnel….” This is not something that one would ordinarily admit in public, not to speak of deliberately calling attention to it in a widely read intellectual journal. What most of the readers may not know is that Professor Rushton has not confined himself to measuring heads. He attained a deservedly brief notoriety in the popular press, especially in Canada, for his interest in penises. He claimed that measurements of the length and angle of repose of that appendage in black and white men showed greater length and a more jaunty angle in blacks, which, according to him, agrees with blacks’ well-known sexual aggressiveness. Ankney’s self- conscious public alignment with the perpetrator of this kind of nineteenth-century silliness does not instill much confidence.

Advertisement

In fact, Ankney’s published paper was not on any new data, but was an attempt at reanalysis, without access to the actual data, of a study by Ho et al.1 which had shown that after body size adjustment there was no consistent difference in brain size between the sexes. The essential difference in the analysis rests on whether one should correct each subject’s brain size for the subject’s body size and then average these corrected values, in my and Ho et al.’s view the correct procedure, or to take ratios of group averages. This is hardly the forum for such a technical discussion, so let me simply restate in exact terms what Ho et al. claimed, a claim with which Ankney does not, in fact, disagree. If a person’s brain size, say the weight of the brain, is divided by the person’s body size, say weight of the body, then the average value of these corrected brain sizes does not differ between the sexes. Depending on what measurement one uses to characterize size, either weight, surface area, or height, the results may show women with slightly larger or slightly smaller brains, but overall there is no consistent difference. It should be noted that since women and men have different average shapes and ratios of fat to bone and muscle, we really have no way of knowing what a “correct” method of accounting for body size would be.

Ankney also cites a study by Andreasen et al.2 claiming that there is a small but real positive correlation between brain size and IQ scores. This is not the first such report, but reports and convincing demonstrations are two different things. The study in question used a small sample obtained by advertising for volunteers in a newspaper, who were then screened (by undisclosed methods) to get a sample of 67. Whatever went on in the process, an extraordinary product was created, because the test subject sample had an average IQ score of 118, whereas the population at large has an average score of only 100 and only about one person in seven has an IQ score above 116. Conclusions from such a nonrepresentative study cannot be taken too seriously. As Andreasen et al. say, “Controversy has persisted for many years about whether there are significant relationships between size and function in the human brain.” It still persists.

Finally we need to observe a contradiction that Ankney also notices in his published writing. If women have smaller brains than men, and if smaller brains produce smaller IQ scores, then women should have lower IQ scores than men. But they don’t. So what’s up? Maybe women make better use of less brain mass, or maybe IQ tests have been biased in favor of women. These explanations call into question either male superior brain power or the objectivity of IQ tests, neither of which is congenial to people who think that there are important issues here that can be solved by weighing brains and giving IQ tests. Then, of course, there is always the possibility that there is nothing to explain, except how people come by their ideologies.

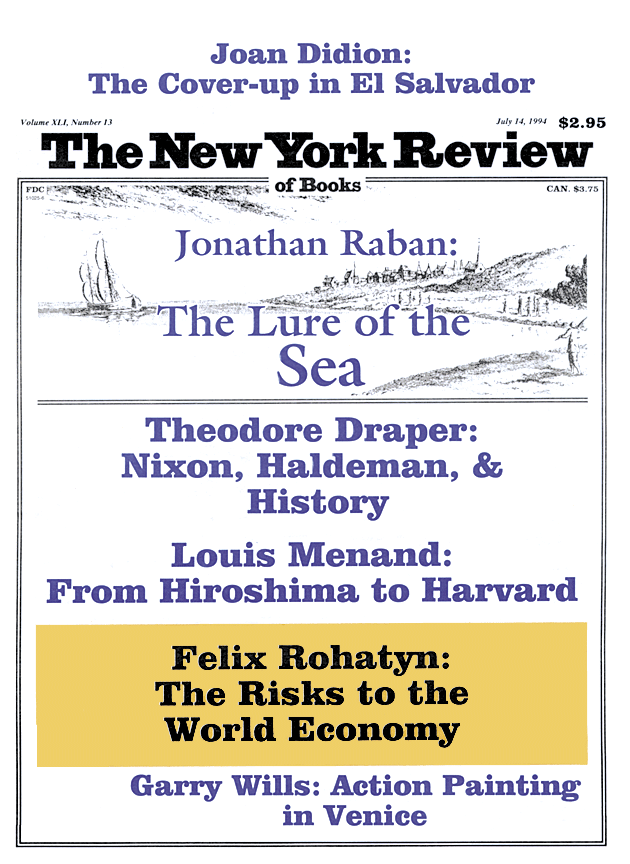

This Issue

July 14, 1994

-

1

K-C. Ho, U. Roessmann, J.V. Straumfjord, and G. Monroe, Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 104 (1980), pp. 635-645. ↩

-

2

N.C. Andreasen, M. Flaum, V. Swayze, D.S. O’Leary, R. Alliger, G. Cohen, J. Ehrhardt, and W.T.C. Yuh, American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 130, No. 1 (1993), pp. 130-134 . ↩