Where does a Harvard undergraduate science major who has listened to Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier “several thousand times” turn to find a ready ear and encouragement for his singular passion? Not, it appears, to any of the notable musicians on the Harvard faculty, but to the even more notable Stephen Jay Gould, who barely raises an eyebrow and signs Eric Altschuler on as an advisee for two whole years. Altschuler produces a senior thesis, we may suppose, consisting of short accounts of each fugue of “The Forty-Eight,” as the British call the Well-tempered, together with numerous miscellaneous glosses. He obtains a vigorous preface from his adviser, secures underwriting from two foundations (Ford, Fannie and John Hertz), hires an agent, and sure enough: his unlikely manuscript is taken up by a major trade publisher.

Survival of the fittest. But Bachanalia is a well-meaning book, for all of its unlikely evolution: sincere, enthusiastic, hard-working, and sometimes ingenious in its effort to help people enjoy music who lack musical training or practical musical experience. The music in question is a limited, specialized, precious repertory, examined in much more loving detail than will be found in most books of “music appreciation.” To be sure, such books tend to be written by musicians, musicologists, or music teachers, not by writers who admit to and indeed insist on the same amateur status as their readers. Altschuler courts his readers in prose “peppered with fascinating lore, abounding in good humor…full of playful, clever analogies to horror movies, human nature, football games, even sex,” as the jacket copy puts it. Downloaded e-mail, it feels like to me, corny in the extreme; but this should not matter much if it works for the job at hand.

What does, in fact, Bachanalia teach about the Well-tempered Clavier? Mainly, and obsessively, it deals with the fugal subjects, the short themes that are heard at the very beginning of every fugue and many, many times thereafter. The heart of the Listener’s Guides that accompany each fugue discussion is a section entitled “Form,” which lists each and every appearance or entry of the subject in the composition—all thirty-seven of them, in one case. 1 Getting his readers and listeners to follow the fugal subject becomes a major concern for this author. Most of his Listening Guides include a “Listening Hint” to help with difficult-to-hear entries.

All this rests upon the conviction, stated many times, that the main thing about a fugue is its subject. The glosses referred to above turn up in the book as miniature chapters or boxes, some grouped together as an introduction and others placed strategically in among the forty-eight fugue discussions. The last of these items, forming an envoy to the book, a veritable benediction, takes off from the story of the man who asks a great rabbi to divulge all the wisdom of the Bible, only to be told,

“Love your neighbor as yourself. The rest is commentary. Now go and learn.”

Similarly, we can say, “The subject is the star of a fugue. The rest is commentary. Now go and listen.”

There is, however, another view of what is central in Bach’s fugues. “It is never the theme which is of central interest in a fugue, but the way the theme is embedded in the polyphonic structure,” writes Charles Rosen. The material that comes in between the subject entries of a fugue, the episodes, cannot be regarded as mere ballast or spacing. Rosen writes, “It is the episodes that largely determine the total movement of the piece, give it its rhythmic continuity, and elaborate the harmonic motion.”2 Episodes develop details of the subject as the subject itself cannot do; they control the direction of the musical ebb and flow by determining most or all the modulations; they are at least as important as the subject entries in setting up the fugue’s cadence structure, which in turn determines its total shape.

As for the subject, if it appears thirty-seven times in a fugue what must be important is the varying contrapuntal web accompanying all those entries. Countersubjects, invertible counterpoint, and the vicissitudes of stretto (the introduction of two subjects in close succession)—all come into play here, with much else. What also matters is not just that entries occur but how—whether they are worked in surreptitiously, for example, or introduced after an expectant pause; whether they proceed into the anticipated answer or into something very different; and above all, once again, how they are coordinated with the fugue’s total shape as articulated by the cadences.

That Altschuler is aware of at least some of this seems clear from a number of discussions in his book. They are rather unhelpful discussions, however. Basically, the only information he gives about episodes consists of listing (and delighting in) sequential ones. He has little to say about cadences, let alone tonality. Invertible counterpoint, always at the octave, is acknowledged on no more than three occasions. The one extended technical chapter, which is in fact a good effort, deals with real and tonal answers to—the subject.

Advertisement

There is a deeper problem still with Altschuler’s project. While most of Bach’s music was indeed written to be listened to, by congregations or by select audiences, this is not exactly true of the Well-tempered Clavier, or true only in a sense that needs special definition. Book I was composed or assembled from older material, in 1722, for didactic purposes: to make a statement about the tuning of keyboard instruments, and for the instruction of the young (some of the assembled material had recently figured in the notebook of Bach’s son Wilhelm Friedemann). Parallel to Book I is Book II, dating from around 1740, though we know less about it. Just a very few of the older pieces in both books appear to derive from a public performance tradition; the others clearly bespeak the private world of the studio, and in certain strictly professional circles the work achieved an underground celebrity. Thirty years after Bach’s death the child Bee-thoven was taught out of the Well-tempered Clavier. It was revered by Schumann and Chopin.

So as the traditional musical canon formed itself in the nineteenth century, perhaps only Handel’s Messiah came to hold so solid a place in it as the Well-tempered Clavier. Yet paradoxically it has never had a place in the musical repertory, that is, in any performance tradition. There was no social setting in Bach’s time for playing these fugues before an audience, nor in Beethoven’s, nor Chopin’s, and there still isn’t today. You are unlikely to have heard anything from the Well-tempered Clavier at a concert recently, or on the car radio.

This music, then, was to be listened to synergically, as it were, in conjunction with being played, while also being looked at in the (hand-copied, probably by the player) sheet music. Though Bachanalia calls itself an “Essential Listener’s Guide,” the activity of listening, as today we listen to music on records, was not essential for Bach. Charles Rosen goes so far as to say that a Bach keyboard fugue

can be fully understood only by the one who plays it, not only heard but felt through the muscles and nerves…. Only the performer at the keyboard is in a position to appreciate the movement of the voices, their blending and their separation, their interaction and their contrasts…. Part of the essential conception of the fugue is the way in which voices that the fingers can feel to be individual and distinct are heard as part of an inseparable harmony.3

This is the mandarin position, and difficult to dispute…though surely the word “fully” leaves a little room for maneuver. Surely just listening, without playing, will reveal much if not the full essence of fugues (the latter ideal being unattainable even to many keyboard performers or, viewed philosophically, to any at all). Surely if one listens intently and repeatedly to music, albeit at first in a limited fashion, sooner or later one will get to hear and understand more.

So, at least, I should like to believe. And so it was with real distress that I came to understand what Altschuler has arrived at, after his thousands of sessions with the Well-tempered Clavier. Another of his major concerns is with rankings, modeled on the Baseball Hall of Fame; he makes much of his choices for the Top Ten Subjects, Top Ten Episodes, and Top Ten Fugues, subdivided into The Superstar Four and The Other Greats. Superstar status is granted to the Fugues in C minor and F-sharp major Book I and C major and E-flat major Book II—short, simple, or very simple fugues with quick, bright subjects; four others of the same general character appear among the Other Greats. But less quick fugues that are complex, rich, and expressive leave Altschuler unmoved. C-sharp minor and F-sharp minor Book I, D-sharp minor, B-flat minor, and B major Book II: he is able to plow through the subject entries in these pieces without revealing so much as a glimmer of aesthetic engagement. A suave, spontaneous miracle like D major Book II fares no better.

How miserable to have listened so often, and to have missed so much! Only one slow piece shows up among the Top Ten, and we also hear of a Long, Slow, and Not My Favorite Club; brevity, in this league, is the soul of fugue. One can imagine the consternation of Donald Tovey, who notoriously disapproved of the slow, expressive D-sharp minor Book I, if he had lived to hear this work described as “long, slow, boring, hateful, odious” (albeit in one of Altschuler’s good-humored passages). But Tovey, in particular,4 and other past annotators and expositors of the Well-tempered Clavier could have helped an innocent enthusiast like Altschuler appreciate some of these slow, rich fugues, just as he is now offering to help others appreciate the quicker ones.

Advertisement

The notion that he might have something to learn, and that his project might profit from reading about the Well-tempered—there exists a substantial bibliography of monographs, student primers, and annotated editions—seems entirely foreign to this recent scion of Harvard. The one book he cites is The Bach Reader, a marvel of positivistic anthologizing which in giving you all the documented “facts” about Bach, unconfused by interpretation, manages also to give the strong impression that nothing else is worth reading.

Nor did Altschuler ever learn about the Well-tempered Clavier from his piano teacher (he never had a piano teacher). She or he would not have needed to point out the subject entries, for with the music stuck up there on the rack, the young Eric could have figured them out for himself. She might have said to bring out that motif a bit more, it’s so nice, lean on this cadence, it’s important, play this line more legato, with more expression, look, like this, and so on. Whether or not she was right every time, she would have given her pupil a sense of the feel of the music, which is quite another thing than a preliminary analytical scheme for it. She is and she has always been, surprising as the thought might be to her, the essential voice of musical tradition.

After an initial impulse, soon stifled, to extend a hand to Altschuler in commiseration, I have turned instead to brooding about today’s musical culture, the culture that produced him. Years ago I floated an idea about Western music history, that it might be viewed as falling into millennium-long phases: initially an oral tradition, with people performing music from memory; then a period of literacy (a term Leo Treitler was using at the time), predicated on scores and partbooks to sing and play from; and now a new model determined by sound recording and the activity (or passivity) of listening. Musicians will have a tendency, and they should fight against it, to brush Bachanalia aside as a case of the deaf leading the deaf. Aloof from performing music, from reading it, and even from reading about it, this book is a true, dismaying product of the new dispensation.

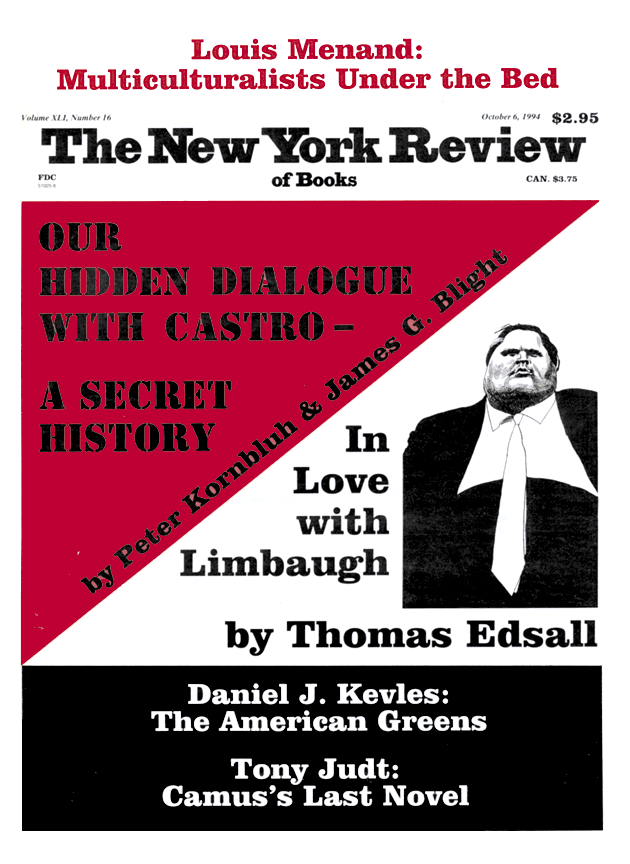

This Issue

October 6, 1994

-

1

There are errors: see the Fugues in F-sharp major Book I and C-sharp minor Book II. ↩

-

2

From the introduction to his Oxford Keyboard Classics edition Bach: The Fugue, edited by Charles Rosen (Oxford University Press, 1975), p. 3. ↩

-

3

Rosen, Bach, p. 3. ↩

-

4

See Donald Francis Tovey and Harold Samuel, editors, Forty-eight Preludes and Fugues by J.S. Bach (Oxford University Press, 1924), preface. ↩