And who, Horatius asked the Romans, will stand at my right hand and fight the bridge with me? And up sprang two volunteers. Horatius was lucky: he wasn’t canvassing Democrats.

President Bill Clinton has begun a month-long campaign to salvage the Congress for Democrats clambering over the side to salvage themselves and leaving him to sink alone.

When the President opened fire in Michigan recently, Congressman Bob Carr, Democratic candidate for the Senate, eschewed the platform for the obscurity of the audience. “I did not invite the president,” Carr told The Washington Post’s Ann Devroy. “I was told he was coming. I have no problem with that…I respect the presidency.”

It is all very well to say that Clinton has not himself shown conspicuous gallantry when challenged to stick fast to a friend in trouble. No fault in the tribal chief absolves the tribesman of duty to his clan. A party that runs out on its president can no longer speak of itself as a party. And yet the Democratic candidates almost to a man and a woman seem ashamed of Bill Clinton and embarrassed by imputations that they may be conjoined with him in the liberalism whose incarnation he is so far from being.

This election is singularly bizarre for its paucity of candidates daring to utter a liberal thought and its abundance of grounds crying out for radical complaint.

The very best that can be said for Clinton’s America is that Newt Gingrich’s will likely be worse. But Clinton’s America is quite bad enough and doesn’t look better for next year.

The most telling index of the social decay over which government presides with complacent indifference was provided by government’s own Bureau of the Census last week. It shows:

—That the median family income in the United States was $44 less a week in 1993 than it was in 1989.

—That the percentage of our fellow citizens with cash incomes below the modest official poverty line had risen from 14.8 in 1992 to 15.2 in 1993.

—That per capita income had indeed risen 1.8 percent in 1993. The catch was, however, in the uneven allotment of that small blessing. In 1968, the poorest fifth of Americans made do with 4.2 of the total national income; by 1993 their share had shrunk to 3.2 percent. Meanwhile the most affluent fifth had ascended from ingesting 42.8 percent of the national income in 1968 to gobbling 48.2 in 1993.

—That, in the year while Democrats and Republicans paltered with before finally abandoning various health proposals, the 38.6 million Americans without health insurance in 1992 were joined by 1.1 million others.

The troubles of the poor ceased a while back to be subject to discussion in a politics where all candidates proclaim themselves servants of the middle class, which could inarguably use a few more, since in the twenty-five years of its highest fashion, the share of the national income assigned to the middle class has fallen to 48.2 percent, a 9-point drop.

And who are those worse off than the middling? They include, of course, the 9.5 million children who exist off public welfare benefits and are widely decried as the most onerous of our burdens despite the splendid endeavors to lighten their load that have triumphed with a near 40 percent reduction in the real value of each one’s grant from the majestic level prevailing in 1975. Even so, discourage him though we have heroically tried, each infant on welfare in New York is still soaking us $46 a week for all his needs.

But then barely half the children who grow up below the poverty line are on welfare. The rest are sons and daughters of the working poor, who are paid at or close to a minimum wage rate unaltered for a decade. Work a forty-hour week at the minimum wage and you’ll earn $10,000 a year. Increasing the minimum wage does not, of course, qualify as a campaign issue.

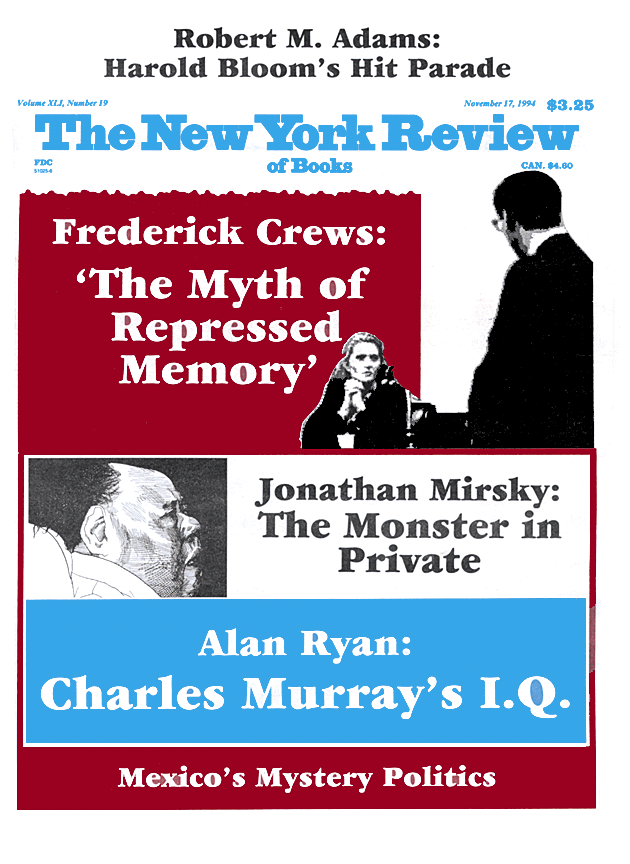

This Issue

November 17, 1994