In response to:

The Tainted Sources of 'The Bell Curve' from the December 1, 1994 issue

To the Editors:

In the Charles Lane review “Tainted Sources” [NYR, December 1, 1994], I note four regrettable errors about Pioneer and one of its founders. The truth is that:

- W. P. Draper was not sympathetic toward Nazi Germany.

- Draper did not advocate “repatriation” of blacks to Africa.

- The Pioneer charter refers to “human race betterment” rather than your sophism of “race betterment.”

- The Pioneer Fund did not propose that America abandon integration.

As to item I above, Mr. Lane gives no citation, and the next succeeding citation doesn’t have anything to do with the allegation. I never heard Draper say any such thing in my years of association with him, and his comments about the Nazi were always opposite to Mr. Lane’s statement. In that connection, it is interesting that Draper served his country in uniform in both World Wars and was severely wounded in trench warfare against Germans in World War I. As to point 2, again no citation is given. And again I never heard Draper say any such thing, and he denied to me a printed rumor to the same effect. As to item 3, this can easily be checked against the charter itself. As to item 4, the “letter” in question, which is based on a secondary source, turns out to be a memo which does not relate to Pioneer at all, and also doesn’t even say what the piece cites it as saying.

I wrote Mr. Lane about the questionable nature of his statements under points 2 and 4 above, but I received no reply. The piece’s sloppiness with the facts is unusual for The New York Review of Books, and I’m afraid it stems from your publishing an ideological polemic masquerading as a book review.

I will not comment on the balance of the review except to note that it seems about the same quality as the foregoing. Charles Murray has appropriately called this book review “McCarthyism” (Wall Street Journal, December 2, 1994).

Harry F. Weyher

President

The Pioneer Fund

New York City

Charles Lane replies:

Let me address Mr. Weyher’s points one by one.

1) “W. P. Draper was not sympathetic to Nazi Germany.”

I wrote that Wickliffe Draper, who founded the Pioneer Fund, “expressed early sympathy for Nazi Germany.” This was based on Draper’s indirect endorsement for Nazi eugenic policy, through one of the Pioneer Fund’s very first grants. In response to a letter from eugenicist Harry Laughlin praising Erbkrank (“Hereditary Disease”), the Nazi propaganda film about Nazi eugenic policy, Draper agreed that the Pioneer Fund would finance the movie’s distribution in the United States. Backed by Pioneer, it played twenty-eight times between March 15, 1937, and December 10, 1938—that is, after Hitler had been in power for five years and information had begun to filter out about the true nature of his “racial hygiene” policies. Draper also financed the translation of German eugenics texts into English. Mr. Weyher does not dispute that Mr. Laughlin, one of the Pioneer Fund’s founding directors, was a public admirer of Nazi eugenics.1

What Mr. Draper may or may not have said to Mr. Weyher about the Nazis or their policies is not germane to this issue, since the two did not meet until about ten years after the war ended. Mr. Draper’s World War I record is irrelevant; in World War II, he served in military intelligence in northern India.2

2) “Draper did not advocate ‘repatriation’ of blacks to Africa.”

According to a 1960 article by Ronald W. May Mr. Draper offered grants to two leading geneticists for research into the genetic inferiority of blacks, and in the course of making this pitch, he noted that the research might help promote the idea of sending blacks to Africa. As the director of a leading university genetics laboratory told May: “Mr. Draper thought the country would be better off without Negroes and believed that the ideas current immediately after the Civil War of repatriating the Negroes to Africa, as was done in the Liberia experiment, could be resumed on a larger scale and would be successful.”

Reporter May sought comment from Mr. Weyher, who was acting as Mr. Draper’s representative at the time. Mr. Weyher did not take the opportunity then to deny that Mr. Draper believed blacks should be sent to Africa.3

3) The Pioneer charter refers to “human race betterment” rather than my “sophism” of “race betterment.”

I wrote that “the fund’s current agenda remains true to the purpose set forth in its charter of 1937: ‘race betterment, with special reference to the United States.’ ” This is accurate, both as a general statement, and with reference to what the 1937 charter said. Perhaps Mr. Weyher is referring to the 1985 amendments to the charter, which make the language a bit more presentable by changing the words “race betterment” to “human race betterment.”4

4) “The Pioneer Fund did not propose that America abandon integration.”

I relied on the London Independent’s characterization of a letter and accompanying Pioneer document, dated November 13, 1989, called “Why Not Study Differences in Race?” which Mr. Weyher had sent to the newspaper’s reporter Tim Kelsey. This document does indeed say “raising intelligence of blacks or others still remains beyond our capabilities.” It criticizes busing “to achieve an arbitrary race composition,” and advances the argument that equalizing the environments of the races will not help reduce the cognitive differences between them.

I concede, however, it would have been more accurate to say that this document mainly advances a case for abandoning compensatory education and other programs aimed at helping blacks, as opposed to criticizing integration per se. I regret this mistake.5

Still, if Mr. Weyher is suggesting the Pioneer Fund has never opposed racial integration he is being disingenuous. He was personally recruited by Wickliffe Draper to help the Pioneer Fund at a time when Mr. Draper was preparing to wage scientific battle against the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Later in that same decade, the Fund financed spurious research into chemical means of separating white donors’ blood from that of blacks’ in blood banks. This year, Mr. Weyher, who now operates the Fund more or less single-handedly, said in an interview with GQ: “That decision [Brown] was supposed to integrate the schools and everybody said we’d mix ’em up and the blacks’ scores would come up. But of course they never did. All Brown did was wreck the school system.”6

The same article’s author wrote that “the fund’s hereditarianism forms a kind of dogma that leads it to venture well away from strictly scientific topics to shape the larger debate over policy implications. Weyher freely admits that he would like to eliminate what he calls “Head Start-type” programs. But, to judge by the grants that it has made, the fund’s administrators are also interested in limiting immigration, stopping busing, reversing integration, and ending affirmative action.”7

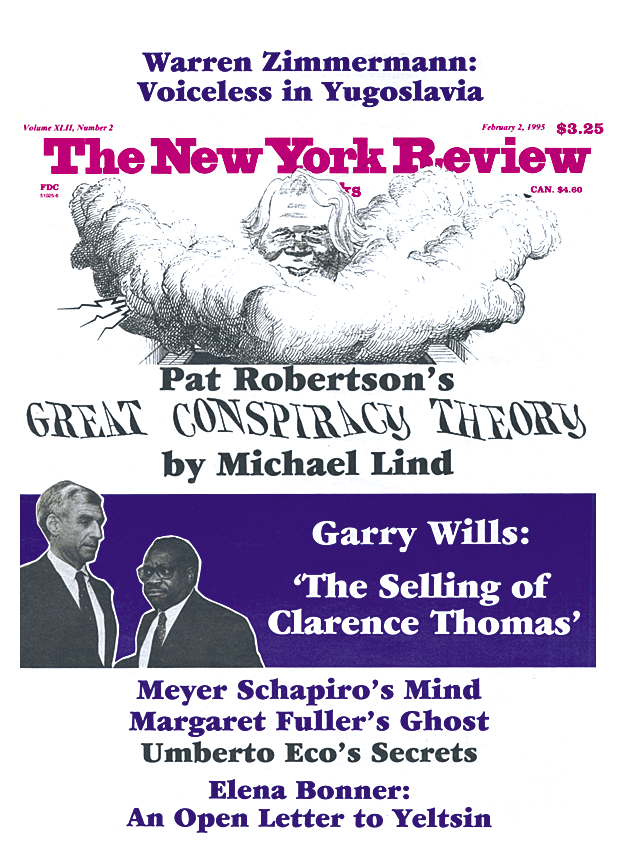

This Issue

February 2, 1995

-

1

Stefan Kuehl. The Nazi Connection. Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (Oxford University Press, 1994), pp. 50, 126. ↩

-

2

“The Mentality Bunker,” by John Sedgwick, GQ, November 1994. ↩

-

3

“Genetics and Subversion,” by Ronald W. May, The Nation, May 14, 1960, pp. 421-422. ↩

-

4

Pioneer Fund Certificates of Incorporation, on file with the New York Department of State. ↩

-

5

“Why Not Study Differences in Race?” November 13, 1989, pp. 1-3, paper provided by the Pioneer Fund to Tim Kelsey of the London Independent. ↩

-

6

“The Mentality Bunker,” p. 234. ↩

-

7

“The Mentality Bunker,” p. 231. ↩