In response to:

Call Me Madame from the December 21, 1995 issue

To the Editors:

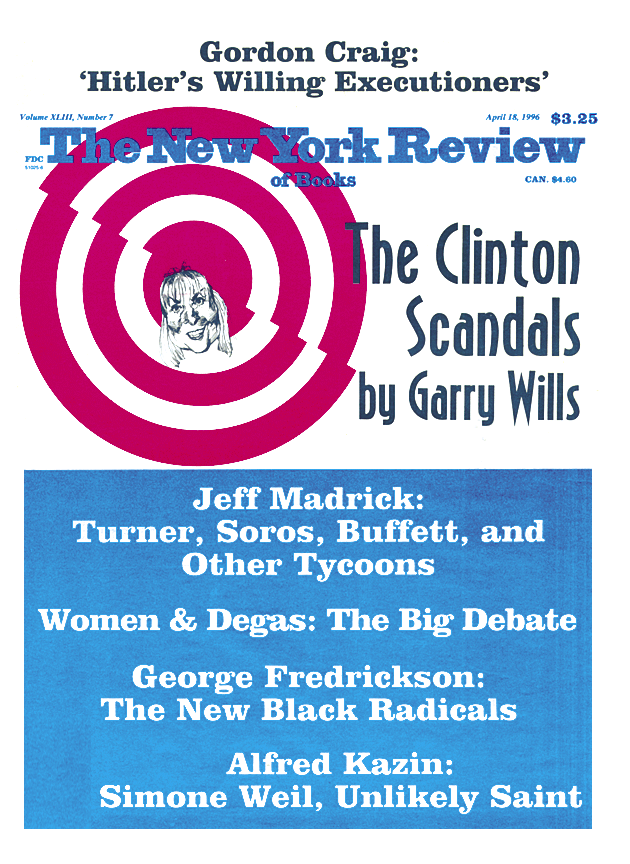

How credulous I’ve become! Little could I have dreamed that so complete a hatchet job, delivered with such unselfconscious pomposity and condescension, in 1995, after a full generation of feminist literary innovation and research, could still be perpetrated against the work of a woman writer as P.N. Furbank’s “Call Me Madame” [NYR, December 21, 1995]. Furbank’s diatribe is in the great tradition of reviewers of Staël’s work that extends from Napoleon, who reduced her to her tits,1 through Herold, whose biography2 served to screw her once more in its very title. And Levine’s caricature of her with arms monstrously swollen to fearsomeness, her nose turning downward into a Levantine sneer, her eyes deeply shadowed, exudes a gypsy-ish cast of “aberrant” femininity, ejecting the author out of the West to which she so patently belongs. Gender “Orientalism” lives.

One would never know, to read Furbank, that the epigraph to Delphine from Staël’s mother’s (Suzanne Necker’s) Miscellany reads: “A man must know how to defy public opinion; a woman to submit.” The novel rings changes on this dictum. My treatment3 of what Furbank terms “weaknesses” in Delphine deals candidly with the problematics for Staël in creating her independent-minded heroine. Like women writers over the ages, she negotiated among severe external as well as internalized censors in attempting to express a version of women’s experience that received opinion would have preferred remain unspoken. For me, pace Furbank, her coming to grips with her authorial evasions illuminates and elevates rather than diminishes her works: it reveals the risks of candor she took, making allowances for her resort to conventional tactics so as better to reveal the work’s strengths. No reader “really” in pursuit of “true judgment” would construe my effort to reconstitute the store of value in Delphine as having done his reductive work for him. To do so utterly falsifies my attempt to rehabilitate an interest in Staël’s novels.

As to Furbank’s irritability with the fawning idealization tendered Delphine’s heroes, is he equally ready to dismiss La Princesse de Clèves, La Nouvelle Héloïse, Great Expectations, and so on? Mocking its surface absurdities, Furbank simply misses the fact that good and evil are far from tidy notions in Staël’s novel. Its ethos reflects the world of the 1790’s—the wake of a revolution waged in the name of Virtue—and its moral canvas so scrambles these terms as to make the moral world of Delphine a deeply ambivalent one. The novel’s force lies in its being, in Staël’s words, “the story of the destiny of women” in her class and time. Its portrayal of the clash of public comportment with private desires, which still dogs women’s full participation in society, is depicted with skill and cunning. Why, one wonders, is Furbank so determined to prevent modern readers from judging for themselves, in the original or in Goldberger’s fine rendition, the worth of this novel?

Finally, Furbank, when not disfiguring my own, bases his reiteration of traditional saws about Staël on Herold’s and Moers’s works.4 Herold’s biography has been superseded by Ghislain de Diesbach’s less sensationalizing life.5 Moers’s brief essay is no match for Simone Balayé’s magnificently documented and probing studies,6 which might have enriched Furbank’s sense of the complexity of a novel he chooses to read as so simple. My study has been followed by a flowering of feminist criticism of Staël’s fiction by Charlotte Hogsett, Marie-Claire Vallois, Nancy Miller, Joan DeJean, Doris Kadish, and, in France, Geneviève Fraisse, as well as other fine critics.7 Their wealth of perspectives dwarfs Furbank’s ill-conceived and, let’s face it, sexist diatribe against Staël’s imaginative works which protest her society’s repressiveness to women. 8

What feminist critics of Staël’s fiction have striven to set forth is a nuanced understanding of works often summarily dismissed through an ignoble blindness inspired by opprobrium unjustly visited upon their author. For all its claims of wishing to separate novel from woman, Furbank’s essay inspired by her Delphine has, regrettably, once more fallen into that trap.

Madelyn Gutwirth

Ardmore, Pennsylvania

P.N Furbank replies:

Madelyn Gutwirth’s terrific onslaught on my review of the new edition of Madame de Staël’s Delphine seems to call for a reply.

She wrote, back in 1973, that de Staël “lacked the courage to defy opinion openly on their [women’s], or her own behalf. The novel (Delphine) curses their common fate: it does not confront it, except by indirection. Nevertheless, even in its timidities, in its fear of angering the men and their satellite women, it is a document in women’s struggle for freedom and her own.” Now to me, and I would have thought to most people, that would seem like saying that Delphine was a pretty bad novel; and since that is what I think too, I can hardly be blamed for citing it in support of my case. If I misunderstood Gutwirth, of course I apologize. As for Delphine being a “document” in women’s struggle, who would think of denying it?

But to come to a more general issue. I hold that literary criticism is a very precious, and rather vulnerable, activity, constantly in danger from a variety of plausible enemies, and that in practice, if not in theory, there tends to be a dangerous gulf between literary criticism and feminist criticism. I seem to detect it in Madelyn Gutwirth’s letter. Her drift is that there are all sorts of “allowances” to be made when judging Delphine or Corinne and that it is crass of me not to have made them. But I doubt if the authors of La Princesse de Clèves, Cecilia, Middlemarch, or The Waves would thank one for “making allowances” for them. To “make allowances” is an admirable thing in everyday human life, but it can have no place in literary criticism.

This Issue

April 18, 1996

-

1

Somehow, this anecdote about Napoleon’s allusion to mammaries recurs irresistibly in a number of commentaries by men. ↩

-

2

Mistress to an Age (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1958). ↩

-

3

Madame de Staël, Novelist: The Emergence of the Artist as Woman (University of Illinois Press, 1978). ↩

-

4

Ellen Moers, Literary Women (Anchor, 1977). ↩

-

5

Madame de Staël (Paris: Perrin, 1983). ↩

-

6

Ghislain de Diesbach, Madame de Staël (Paris: Perrin, 1983); Simone Balayé, Madame de Staël-lumiëres et liberté (Paris: Klincksieck, 1979) and Madame de Staël-écrire, lutter, vivre (Geneva: Droz, 1994). Balayé’s output of articles is such that I can’t begin to list them here. ↩

-

7

Charlotte Hogsett, The Literary Existence of Germaine de Staël (Southern Illinois University Press, 1987); Marie-Claire Vallois, Fictions féminines: Mme de Staël et les voix de la Sibylle (Stanford: Anma Libri, 1987); Carla Peterson, The Determined Reader: Gender and Culture in the Novel from Napoleon to Victoria (Rutgers University Press, 1986); Nancy Miller, Subject to Change: Reading Feminist Writing (Columbia University Press, 1988); Joan DeJean, Fictions of Sappho (University of Chicago Press, 1989); Doris Kadish, Politicizing Gender (Rutgers University Press, 1991); Geneviève Fraisse, Muse de la Raison (Aix-en-Provence: Alinéa, 1989); Avriel Goldberger, Madelyn Gutwirth, and Karyna Szmurlo, editors, Germaine de Staël: Crossing the Borders (Rutgers University Press, 1991). This list is not exhaustive, but merely indicative of the availability of fresh thought, were one genuinely anxious to find true judgment. ↩

-

8

If Furbank sides with Herold to rehabilitate her at the end of his piece, this is to praise her for her works in which such protest is mute or muted, and because fundamentally he cannot deny her stature as a major literary figure. ↩