For years you couldn’t go to a tap-dance revue in New York without seeing a skinny little boy named Savion Glover brought on at the end to do improvisation. Maybe Glover didn’t have time to work up a regular number, for he was a busy child, a star on Broadway from the age of twelve (The Tap Dance Kid, Black and Blue, Jelly’s Last Jam). He also danced in movies and on TV, and presumably he had some homework to do in between. But often it seemed that the reason he couldn’t be programed alongside the other acts was that he so outshone them.

“Savion is possibly the best tap dancer that ever lived,” Gregory Hines recently told The New Yorker.1 The odd thing is that this was true ten years ago, when Glover was twelve. His foot seemed to have about eight mobile parts. He was a whole band. And what speed he had! He could run you up and down long staircases of sound in ten seconds. He was witty too, tucking tiny, sharp sounds into long, soft ones or, when he got to a clear stopping point, pushing the dance over a hump and sending it down a whole new road.

Like all child prodigies, however, he was a little strange, for he wasn’t yet old enough to make art out of this huge talent—get it to say something instead of everything. As an adolescent he was even more disquieting. While dancing, he would bend over and look at the floor. He didn’t seem to realize he was in front of an audience. Occasionally, he would pause in the middle of a routine and just stare out into some corner of the auditorium, as if waiting for his next idea. He didn’t know when to get off the stage, either. People had to signal him from the wings: “Wrap it up, Savion.” Also, he broke things. Once, I remember, his hand got caught in a string of beads he was wearing, and the beads flew like buckshot all over the stage. The musicians had to duck. Other times, the taps would fly off his shoes (more ducking). And at this point he was bringing down his feet so hard that it seemed he would break through the floorboards.

A smoldering teen-ager, with unparalleled gifts—what would he make of himself? one asked. Now, with his choreography for Bring In ‘da Noise, Bring In ‘da Funk, which has just opened on Broadway after a three-month run at New York’s Public Theater, he has answered.

Conceived and directed by George C. Wolfe, the producer of the Public Theater, Noise is as politically pointed as other shows that Wolfe has directed (Angels in America) or written and directed (Jelly’s Last Jam). On its surface, it is the tale of the Africans’ exile in America, from the arrival of the slave ships down to the present, but nested inside this fable is another one, the story of the exile of tap. The show’s subtitle is “A Tap/Rap Discourse on the Staying Power of the Beat,” and the discourse goes as follows. Black people have natural rhythm. (Weren’t we supposed to stop saying this?) Or, to use Noise’s terminology, they have “‘da Beat,” and it came over with them from Africa. White people did everything possible to kill the Africans’ beat: took away their drums, lynched them, ground them down. And by the 1920s black people very nearly had lost the beat, by dint of trying to share it with white people—here we are shown a black cabaret singer, draped in rhinestones, singing, “I got the beat / You got the beat / The whole world has got the beat”—or by watering it down for consumption by white people, and here we are treated to nasty sendups of the superb black entertainers who made their living in Hollywood in the Thirties and Forties.

A dancer impersonating Bill “Bojangles” Robinson is shown doing Robinson’s famous stair dance while hymning the rewards of Uncle Tom-ism (“Dont worry bout me / Ackin de shiffless fella / I got lots a money / N’ a fine high yella”). A pair of smoothies named Grin and Flash check their cufflink alignment, pat their tuxedos, put on big smiles, and thereby tell us that the Nicholas Brothers and their colleagues—the flash acts (acrobatics), the class acts (precision, elegance)—were just a bunch of sellouts. Then, suddenly, these beat-less apostates vanish, and what remains on stage is just Savion Glover, the show’s lead performer and, as we now find out, the savior of tap, dancing to a tape of his own voice.

“Hollywood, they didn’t want us or something,” the voice-over says. “They wanted to be like entertained.” Certain old tappers—he names Chuck Green, Lon Chaney, Buster Brown, and Jimmy Slyde—eschewed entertaining. They hung onto the beat; they went on hoofing. “See, hoofin’ is dancin’ from the waist down…. People think tap dancin’ is arms and legs and this big ol’ smile. Naw, it’s raw. It’s rhythms, it’s us, it’s ours.” Central to hoofing is “hitting,” or saying something real, and you can’t do that with arms and smiles. From Green, Chaney, Brown, and Slyde, Glover learned to hit: “I never did go back to like flap-flap-shuffle-step…. I don’t see how people would wanna see that old school or like old style of tap dancin’ when they know there’s some real hittin’ goin’ on over here…. Hit it. [He’s dancing now.] Hit it. Hit it.”

Advertisement

As tap history, none of this is especially accurate. Tap dancing was born of the convergence of African dance with other percussive dance styles (English, Irish, Scottish) on the American continent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It did not really become what we call tap until the end of the nineteenth century, when the music it was associated with became jazz. In large measure, tap was the dance version of jazz. Accordingly, it was about rhythms, which were sounded by the feet. Still, those feet were attached to something. One of the specifically African qualities of tap was the involvement of the whole body. Even today, a quality that often sets black tappers apart from their white colleagues is their easy, elegant coordination of upper and lower body. (Now as in past centuries, white dancers tend to be stiffer upstairs.) So there are many black tap dancers who would be very surprised to learn from Savion Glover that their art is practiced only from the waist down. And Jimmy Slyde, who until recently was appearing every Thursday night at La Place on West Fifty-eighth Street, would be additionally surprised to hear that he is not interested in entertaining.

As for tap’s being “raw” and “us,” one expects, hearing this, to see Leonard Jeffries lowered from the flies to tell us about the “Sun people.” Robert Brustein of The New Republic, in one of the few uncomplimentary reviews of the Public Theater’s production of Noise, objected bitterly to its dismissal of white tappers.2 But forget white tappers. There is not a black tapper from 1900 to 1950 whose memory is not dishonored by the show’s representation of tap’s traditional elegance and gaiety as falsehood, hypocrisy.

How much of Glover’s monologue is Glover as opposed to Wolfe? As noted, it comes immediately after Wolfe’s mean-spirited satires on black stars of the Thirties and Forties (in which, I forgot to mention, Billie Holiday and Hattie McDaniel also take it in the neck). And Glover’s notions about “hoofing” and “hitting” fit right in with the show’s overarching mystagogy about “‘da Beat.” Still, Glover may sincerely embrace these views. He is a young black male, and the positions taken by the show—that all accommodation is wrong, that no one working within a cruel political system can ever be happy or admirable, that what is “us” is tough, angry, “hitting”—are not unpopular with young black males these days. Indeed, Glover may even be young enough to believe that he alone is presiding over the resurrection of tap.

If so, he may be right, for however blind and ungenerous the show’s view of history, its choreography—Glover’s choreography—is so good that it redeems the whole enterprise. Glover seems to regard tap as an infinitely extensible form. Hence the range of the fifteen-odd dance numbers that he has created for the production. There is a machine dance, in the manner of the Russian Constructivists, with the dancers as pistons and cogs. We also get a cakewalk and a Charleston and a nice, hoppy, old-fashioned buck and wing. Sometimes the four lead dancers look like boys in a schoolyard, passing a phrase like a basketball. Elsewhere they are not boys or even men, but just their dance. In a section about Harlem during the 1977 blackout, the four of them simply move forward, from the back of the stage to the front, in what seem like fixed slots, their feet drumming a relentless phrase—the four tappers of the apocalypse. It’s a pushy number, but thrilling.

And in every dance, Glover has managed to make the tapping communicate not just as music but as narrative. In the “Slave Ships” section, we see only one figure (Glover), sitting on the floor and leaning back, as though in the galleys of those fateful ships. Haltingly, he rises and executes a series of very slow ronds de jambe (semicircles on the floor), trying to find his legs again. Meanwhile, in the scraping of his metal taps on the floor, we are made to feel the chains. In the dance that follows, a group of field workers inherit the scraping ronds de jambe, which they perform slowly and mechanically, like ghosts, until suddenly, with a burst of music, they erupt into a series of fabulous solos, their legs flying out as if they would fly off. It’s almost frightening, this cataclysm of energy rising out of the gloom of the scraping figure. In the next dance, “The Lynching Blues,” the two extremes have compromised on a medium-speed, beautifully syncopated dance, the buck and wing, performed atop a bale of cotton by the excellent Baakari Wilder. In this series of historical episodes, Wilder’s solo is the first sustained image of individual mastery, of the African as artist, and it ends with his being hanged. Even if we don’t buy Wolfe’s primitivist notions about the persistence of the beat, it would be hard not to accept Glover’s dance imagery here as indicative of some kind of strength, perhaps even moral rather than instinctive.

Advertisement

Partly because of their narrative force, but also because of their clear musical structure, with rhythmic patterns developing, disappearing, reappearing in new forms, these are dances that you can get your brain around. The version of tap history retailed by Bring In ‘da Noise is correct on one point: tap has been a limited form. This is partly because of the venues in which the dancers worked. Tap did much of its growing up in vaudeville, where, as Donald O’Connor pointed out in a recent interview, “You never changed your routine.” O’Connor spent his whole youth in vaudeville, during which time, he says, “I learned just two or three dance routines, and I never learned anything else…. People wanted to see the same thing…. That’s what they paid to see.”3 In the nightclubs and stage shows and even the movies, the pressure was the same: do your specialty and don’t mess with it. Warren Berry, of the Berry Brothers, a beloved flash act of the Thirties and Forties, says that he and his siblings performed their cane dance for what seemed like thirty years. (“I hated it.”) Some few dancers managed to avoid being typed, notably Fred Astaire, but Astaire worked in feature films whose subject was dancing, and whose choreography was under his sole direction—an advantage shared by very few other dancers of his time (to my knowledge, only Gene Kelly and Eleanor Powell), and by no black dancer.

So tappers worked within tight restrictions, and the energies they could not use in varying their acts they spent on other things—for example, charm, personality, those qualities so scorned by the makers of Bring In ‘da Noise. According to Fayard Nicholas, of the Nicholas Brothers, Bill Robinson’s routines were often quite simple: “Someone else did that, nothin’ would happen. But he had this personality.” And the play of personality inflected the steps, gave them drama. Other dancers, particularly after World War II, as bebop edged out swing, built on their regular acts via extended improvisation. Some of this was thrilling, still is—bebop improvisers are still working (e.g., Jimmy Slyde)—and it enriched the art, but finally it seemed yet another aspect of personality, and often a hermetic one.

All these years, tap went on developing—in technique, in rhythmic sophistication—but it developed inward rather than outward. It dove into itself, creating ever-finer microstructures of sound. As a result, it became one of the least knowable of dance forms. You might love it, but unless you were a tapper yourself, it was hard to parse it, even remember it. In consequence, it was rarely written about. I checked my local Barnes & Noble a few months ago. In the music department, there were thirty-four histories (not counting biographies) and seven encyclopedias of jazz. In the dance department, there were exactly two books on tap.4 One can give various reasons for this: that music criticism is a larger and older field than dance criticism; that any dance critic who wanted to write about tap had to be a music critic as well. But I believe the main reason is that for most spectators tap occurs in a kind of Bergsonian time—all present, no past or future, like a snake going around a corner. They cannot find its shape, let alone its meaning, its relation to life.

These are the problems that Glover has overcome in Bring In ‘da Noise, and not a moment too soon. Tap went into a major slump in the Fifties, the result of the drying up of its venues: nightclub shows, Broadway and Hollywood musicals. Then, in the Seventies, with the rise of black consciousness, it was revived. There still wasn’t much commercial demand for it, but this time, its enthusiasts claimed, it wasn’t a commercial property; it was an Art. And so, like the other arts—but more so, since fewer people consider it an art—it has been hanging on by its fingernails ever since. In the past twenty years, black tappers’ paychecks, when they got paychecks, have often come from the politically sensitive grants panels of the NEA and NEH or from dance festivals, particularly in Europe, where black tap is regarded as an interesting American folk art.

What tap needs now is some beneficent jolt, something to jump-start it again. A new star would help, and there has been at least one, Gregory Hines, who was Glover’s mentor and foremost model. (Where was his name in the list of those who remained true to the beat?) But as Hines himself has acknowledged, there has never been a tap dancer like Savion Glover. Will Glover choose to become a star as well as a virtuoso? At present he seems to be shying away from stardom. The clothes he wears in Noise look as though they were fished out of a dumpster, and he still bends over when he dances. (In his long monologue-solo, he actually performs with his back to us; we have to watch him in a mirror.) He can’t act, or doesn’t try to. Presumably, this is all part of his sensitivity about tap’s flash-and-grin past. For the moment he doesn’t want to be charming.

But more than an outgoing performer, what tap needs is some extroversion in its choreography, someone to release it from its inwardness, make it tell stories, convey emotions other than rhythmic rapture. And this is what Glover has done. If he doesn’t want to make friends with the audience, his dances do, and that’s enough for the present. He is twenty-two, and this is the first show he has choreographed.

Bring In ‘da Noise has many elements besides dance. There is a self-styled “rap” text, a long, hallucinatory poem that threads its way through the show and is sometimes effective when (about half the time) the words can be heard. In the new Broadway version, the text is spoken by Jeffrey Wright, who played Belize, to great acclaim, in Angels in America. He overacts, but he’s still better than Reg E. Gaines, the author of the text, who in the Public Theater production spoke the poem himself, meanwhile hopping up and down continually as if he were being electrocuted by his sneakers. The score, consisting of new blues, rags, and so on, is by Daryl Waters, Zane Mark, and Ann Duquesnay. It is just fine and nothing special. Drumming is crucial to the production—there are two numbers that are nothing but drums—and the drummers, Raymond King and particularly Jared Crawford, could not be better. Apart from Glover, there are four dancers—Vincent Bingham, Jimmy Tate, Baakari Wilder, Dulé Hill—and beside him, they are what four excellent actors would be in a show starring Olivier. (Actually, Wilder, who does the buck and wing, is a star himself.) The set is mostly slides: slave ships, historical photos.

Near the end there is a Hallmark-card section where we are shown slides of the dancers and drummers in rehearsal while they tell us, in voice-over, how God and music and their mothers kept them off the street while other guys they know took drugs and went to jail. I dislike this interlude not just for its sentimentality, but because it seems to say that what these young men have done by way of art is just impersonation, that what they really are is lives, black lives. But they are not just lives; they are artists. This misunderstanding is related to everything that is wrong about Bring In ‘da Noise. For Wolfe, not only does a show by black people have to be about race, but the black people who put it on have to be presented to us as data in the history of racial politics. How long, O Lord?

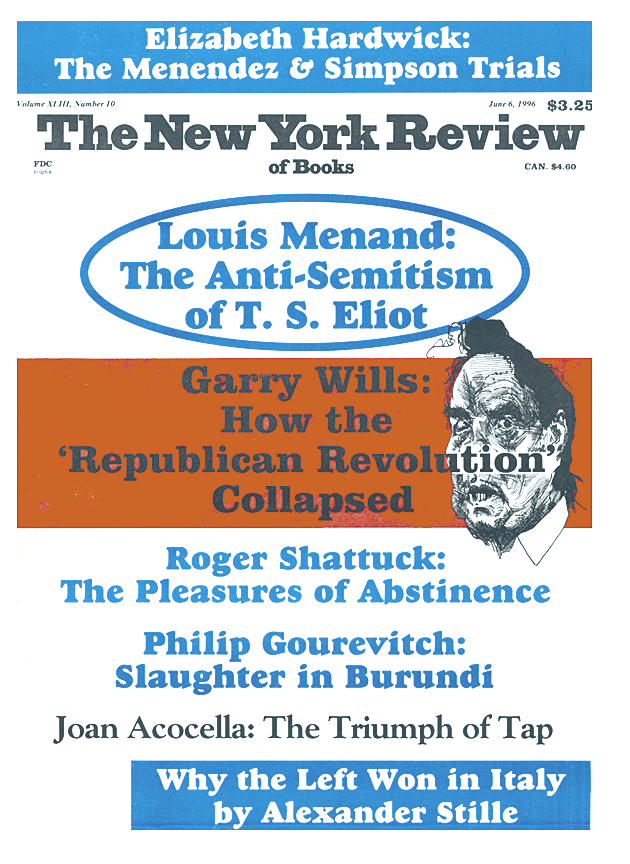

This Issue

June 6, 1996

-

1

John Lahr, “King Tap,” The New Yorker, October 30, 1995, p. 90. ↩

-

2

“More Noise than Funk,” The New Republic, March 4, 1996, pp. 31-32. ↩

-

3

O’Connor’s statement, and the later quotations of Warren Berry and Fayard Nicholas, are taken from Rusty E. Frank, Tap! The Greatest Tap Dance Stars and Their Stories, 1900-1955 (1990; revised edition, Da Capo, 1994), pp. 151, 160, and 73, respectively. ↩

-

4

Frank’s Tap! and Marshall and Jean Stearns’s Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (1968; revised edition, Da Capo, 1994). Both are very useful, but they are largely historical and anecdotal rather than analytic. ↩