In response to:

The Hovering Life from the January 11, 1996 issue

To the Editors:

William H. Gass, in his “Hovering Life” encomium to Robert Musil’s newly translated Man Without Qualities [NYR, January 11], engagingly depicts the unique charm, challenge, and rewards of the novel’s first half. For the whole second half, though, he has but a few off-the-mark sentences to spare. “Fallen fruit,” he calls Ulrich’s relationship with his sister Agathe; she arrives “much too late”; she serves only as Ulrich’s “Siamese twin” with whom he either goes to bed or doesn’t, depending on which of the “unfinished versions” one prefers. For Gass, Agathe’s significance appears exhausted in this reflexive, weirdly self-incestuous function, as if she were no real character but just a bizarre personification of Ulrich’s “other, sought-after half”—some variable of him.

One suspects that Gass’s long night at the airport was too short for him to finish reading the book, or at least to think much about its latter parts. The oversight results in an assessment less than fair to Musil and his translators. Potential readers deserve to know that it is precisely in the MWQ’s second half, following Agathe’s entrance (indeed late, but not incongruously so), that Ulrich’s search for authenticity moves from the preparatory, largely ironic probings which Gass elucidates so winningly into serious, flesh-and-blood experiment and risk. As they explore their tantalizingly sensual but (at least temporarily) non-sexual “sibling love,” Ulrich and Agathe discover realms of significance intensely moral and even quasi-mystical, while nonetheless keeping their grip on everyday, reliable reality.

Next to Ulrich, Agathe is the most important character in the novel. She is the only non-caricature in the motley cast besides Ulrich himself. Her insights, her naive challenges, her active courage that draws her into “improper,” even illegal areas where Ulrich fears to tread, provide the ideal supplement and corrective to his clever but maddeningly timid ramblings. Ulrich returns the favor by introducing Agathe to a down-to-earth, responsible sense of precision that her judgments had heretofore lacked. Musil weaves their thoughts, feelings, and borderline taboo experience into a multilayered fabric unmatched in the modern literature of love.

It’s too bad we harried denizens of the Nineties have so little time for truly rewarding tasks, like reading the MWQ through to its ephemeral “end.” But since that is so, here’s a tip for impatient readers who may have bogged down in the Collateral Campaign. Rather than lay the book aside, go straight to Section III, where thanks to Agathe things really start to crackle for Ulrich and for us. Or if that still leaves too many pages to tackle, jump to the final section, i.e. Musil’s withdrawn galley proofs and other drafts translated by Burton Pike alone, and read them with their 1940-1942 “alternate draft versions” through Chapter 52. Chapters 45-48 of the galley proofs, then 49-52 of the “alternate drafts,” contain passages among the most provocative, evocative of Musil’s entire prose opus. Knopf and Burton Pike have done their part by rescuing them from sad obscurity. The rest—the reading, the savoring—is up to us.

Philip H. Beard

Professor of German

Sonoma State University

Rohnert Park, California

William H Gass replies:

a. I remain of the opinion that “the second half” of The Man Without Qualities develops in a way which is not fully integrated with its first “finished,” better-known half, though it might have been made to do so had Musil had both world and time enough.

b. There is considerably more scholarly dispute about the “second half” which would have required far more development than I had time or space for if any supportable judgments were to be made about it.

c. Professor Beard is welcome to plant his flag in the later parts as if they were an undiscovered country if he likes. I used to do that with Finnegans Wake until I discovered it was the middle that never got read. Certainly what Burton Pike has given us is a great gift.

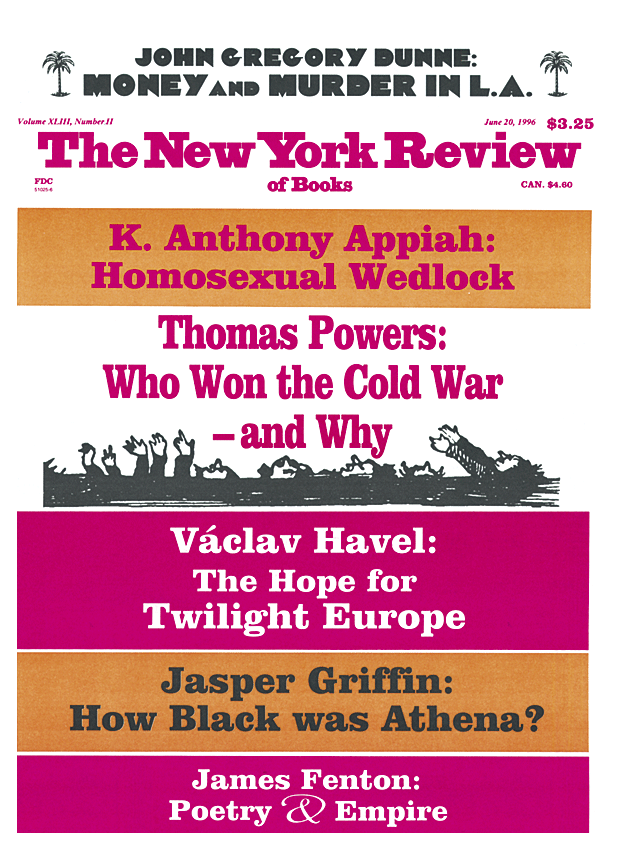

This Issue

June 20, 1996