In response to:

The Rise & Fall of a Half-Genius from the November 14, 1996 issue

To the Editors:

I am the (un-named) ex-member of R.D. Laing’s Kingsley Hall “who wrote a satirical novel about his stay…,” cited by Rosemary Dinnage in her informative review of books by Daniel Burston and Bob Mullan about Dr. Laing [NYR, November 14]. I would like to offer an alternative view of Laing and his work, based upon my years of working with his Philadelphia Association and its outgrowth, KingsleyHall. (I was a co-founder of the Hall, and for a time Chairman of the PA.)

My biggest problem with Dinnage, and perhaps with the books under review, is that they focus on the personality—the star!—rather than the patients Laing helped and hindered, saved and killed. Laing’s legacy, if there is one, is to be found among these scattered individuals, including the patients of his disciples and trainees. The trouble is, this legacy is largely unquantifiable because the “illness” Laing sought to “cure” remains bafflingly elusive and unsusceptible to easy medical labels.

If Laing had a genius it was the persistence with which he insisted, against conventional medical wisdom of the time, that schizophrenia was an experience and not a sickness. Stated so baldly, this may imply (as we daftly felt, at times) that schizophrenia is a good thing…the “ecstatic voyage” leading to self-healing and all that. But Laing and his co-workers knew, from grisly clinical experience, that most schizophrenics are desperately unhappy, trapped in their misery and confusion, profoundly despairing and a source of unimaginable pain to their families who may, or may not, have contributed to the condition in the first place. Still, Laing and his comrades (as he often called them), demanded, and fought for, respect for the schizophrenic, regardless of how bizarre or alarming the patient’s behavior. This was a functional respect that took the form, whenever possible, of avoiding palliative drugs, electro-shock, traditional diagnosis and the formal distancing of doctor from patient which Laing equated with soul-murder.

Incidentally, pace Dinnage, in the seven years I knew and worked with Laing, I never once heard him “(emphasize) that drugs and electric shocks are all right in their way, if they are acceptable to the patient.” He despised the use of drugs, including insulin and shock therapy, in schizophrenic treatment. But, as a macho Glaswegian, he knew—as we all knew—that sometimes you had to temporarily dope an uncontrollable patient to save your life or his/hers. But I cannot overstate his horror of drug therapy for the mentally ill. Mainly, he felt the drugs were doled out to alleviate the doctor’s anxiety not the patient’s.

Laing was not just a Byronic poet of medicine whose lonely star shot out into the dark universe and blew up in an orgy of self-indulgence. He closely worked with a number of people, some well-known and medically qualified, some unknown and “barefoot nurses” like myself. You cannot talk about Laing without also mentioning such colleagues as the South African existentialist, Dr. David Cooper, and Dr. Aaron Esterson with whom Laing wrote some of his pioneering essays on the family. More interesting than the faintly glamorous Kingsley Hall was Dr. Cooper’s grubby, glorious Villa 21, an experimental ward for young, florid schizophrenics at the state-run Shenley Hospital in Hertfordshire, which Cooper ran with a brilliant Liverpool nurse, Frank Atkin. These names are not just historical footnotes. They were brave, talented human beings without whose support, friendship, and practical collaboration Laing would have sputtered on the pad and disintegrated much earlier than he did.

A final note. The prevailing view is that Laing blew himself out of the water with drugs, drink, over-celebrity (and maybe even too much screwing). Perhaps. My own opinion is that Laing was one of the many doctors and nurses (including Cooper and Atkin) whose too-close proximity to the fierce heat of schizophrenia burned them out via over-identification with their patients. Working with the “loony” you are very tempted to cross the line as an act of solidarity and because you have convinced yourself that therapy-at-a-distance is a betrayal of the tortured and self-torturing patient. There is plenty of room for argument about whether this is a good or harmful thing to do. But, Mary Barnes aside, there are a number of men and women alive and functioning today because a few good doctors, nurses, and their well-meaning if clumsy accomplices had the guts walk into the furnace and stay there till the job was done.

The great tragedy is that Laing did not live to settle down into a medical practice he grew to loathe; to temper his views; and to become the real human being he always felt his patients could help him to be.

Clancy Sigal

Los Angeles, California

Rosemary Dinnage replies:

Clancy Sigal’s letter is very welcome in that it describes aspects of R.D. Laing’s life that neither of the books under review was able to do. Perhaps no ex-patient of Laing’s or Laingians who are “alive and functioning today,” as Sigal says, “were traced or interviewed.” The strain of working with and identifying with his patients may indeed have contributed to Laing’s distress. As for his views on the occasional use of psychiatric drugs, I was referring back to pages 192 and 379 in Mad to be Normal.

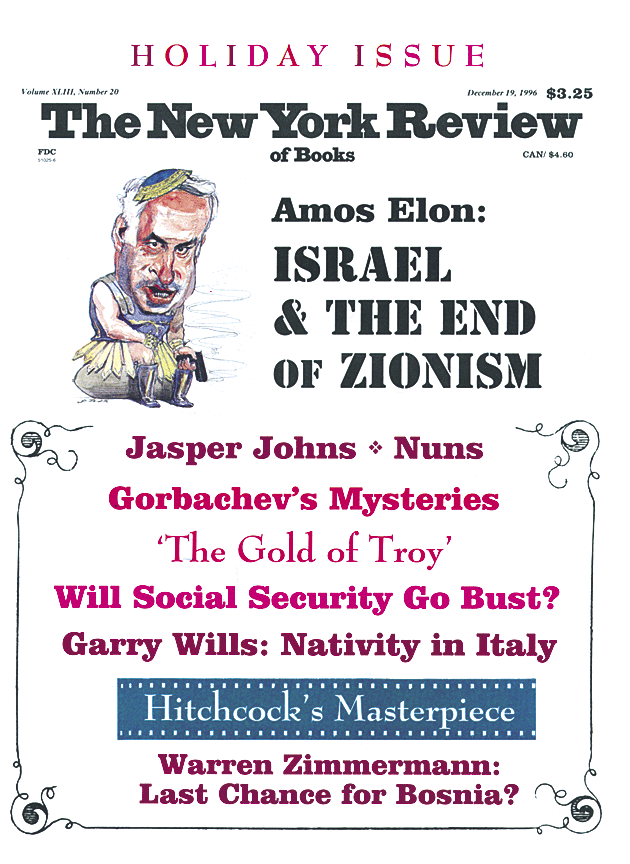

This Issue

December 19, 1996