1.

During the past decade, a major new development in the relations between American workers and businesses has been quietly taking place. Ignored by most business leaders and government officials, it has also been overlooked by the press, which has been preoccupied with the damage downsizing has done to workers’ lives. It is a trend toward a new kind of corporate culture in which the interests of managers, shareholders, and workers are closely and deliberately linked. The devices linking them include profit sharing and employee stock-ownership plans.

The experience of a number of successful companies, as well as large-scale statistical studies, show that these “collaborative” methods can improve productivity and raise workers’ incomes. They can also increase employment and thus help to ease the deep economic uncertainty that affects many American workers. Although it is true that such developments are taking place only among a relatively small number of companies—perhaps 10 percent, perhaps more—it is also true that the number of companies that are experimenting with them is increasing.

The appearance of collaborative corporations is heartening because, in spite of rising stock markets, low inflation, and low unemployment, the American economy still has deep problems. Whatever the outcome of the current controversy over whether average earnings have been falling for the last twenty years,1 income inequality has increased markedly over the last two decades and shows few signs of shrinking. Both white- and blue-collar workers remain anxious about their economic security. To improve productivity, corporations have largely come to rely on cost-cutting measures such as downsizing and outsourcing—replacing in-house labor with outside contractors or less expensive temporary workers. The result has been called a “new, ruthless economy,”2 in which many of the arrangements that traditionally were made between workers and their employers—including relatively stable jobs with benefits such as health and retirement plans—have been eroded.

Perhaps the best-known example of the alternative, collaborative approach is United Airlines. When its employees acquired 55 percent of the company’s stock in July 1994 in exchange for reduced wages and benefits and other concessions valued at approximately $5 billion, the sheer size of the country’s largest employee buyout caught people’s attention.3 So did the arrangements by which United employees gained majority voting rights in the company as long as they continue to own at least 20 percent of the company’s stock. They also got increased job security and three out of twelve places on the board of directors, as well as veto power over major company decisions. Labor Secretary Robert Reich hoped that such a highly visible example would make employee ownership a more likely possibility for companies trying to reduce costs and increase productivity and profitability. “From here on in,” he said, “it will be impossible for a board of directors to not consider employee ownership as one potential business strategy.”

While this prediction has turned out to be overoptimistic, United has made a promising start under employee ownership. The company quickly gained a larger share of the market, and it has increased productivity and profitability more rapidly than its competitors. It also increased employment by eight thousand workers while its rivals were retrenching. These achievements have been reflected in its stock price, which has roughly tripled since the buyout, compared to increases of about 30 percent in the shares of other airlines. (Recent disputes between management and employees at United over wages are, ironically, in part owing to its very success: the employees want a greater share of its profits, which management is determined, instead, to reinvest in the company’s continued growth.)

Business Week attributes United’s progress to “once unimaginable cooperation” between workers and managers. For example, after the buyout a group of pilots, ramp workers, and managers devised a simple way to use electricity instead of jet fuel when planes are idling at the gate, thus saving the airline about $20 million a year. The only capital investment required was longer ladders so the ramp workers could plug in the electric cables. “In the past, we would have sent out an edict and nothing would have changed,” the executive in charge of fuel explained.4

There are several key measures common to all efforts at transforming companies from hierarchical enterprises, in which managers unilaterally make decisions, into more cooperative, incentive-based businesses. First, workers are given more direct responsibility and control over their jobs. Second, they are given the training and information necessary to exercise their new responsibilities. Third, part of their compensation is linked to their performance. In many cases, workers are also given assurances that layoffs will be used only as a last resort. Without such assurances, they will be less likely to support labor-saving improvements.

Employees, as we shall see from a variety of studies, tend to be happier, more productive, and better paid under collaborative or participatory work arrangements. These arrangements, however, are often difficult to carry out. Not only must the work force be reeducated, but managers must be persuaded to accept diminished authority. This may explain why many firms, perhaps against their long-term interests, have instead relied on cost-cutting measures such as downsizing and outsourcing in order to boost productivity.

Advertisement

But these measures appear to have been less successful than anticipated. Recent research has shown, for example, that manufacturing plants in which productivity rose but employment fell accounted for just slightly more of the total increase in productivity from 1977 to 1987 than did successful “upsizers”—plants in which both productivity and employment increased.5 American Management Association studies of firms that have cut back their workforces since 1990 found that fewer than half raised profits and only a third increased productivity. Approximately 40 percent of executives at the companies surveyed were unhappy with the results, and the surveys showed that productivity improvements from measures like downsizing may simply be limited because of their impact on company morale and the proportion of workers who subsequently leave the company. The remaining workers are often susceptible to “burnout” from being expected to take on too much work, particularly in periods of growth. This may explain why the shares of firms that downsize outperform the stock market in the first six months, but tend to underperform after three years.

United’s employees acquired their shares in the company through an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP), a pension plan that requires a majority of its assets to be invested in the stock of the sponsoring company, and is allowed to borrow money (to use “leverage”) to do so. Louis Kelso, a San Francisco lawyer, set up the first leveraged ESOP in 1956 to purchase majority control of Peninsula Newspapers in Palo Alto, California. He saw employee ownership as a means of giving workers a “second income” from their share in profits, which in turn would help resolve the “under-consumption” of goods and services by which Kelso felt American capitalism was plagued. The use of ESOPs to broaden the distribution of income and wealth appealed particularly to Russell Long, the populist Louisiana Democrat and influential chairman of the Senate Finance Committee who was instrumental in gaining Congressional support for ESOPs in more than fifteen pieces of legislation between 1973 and 1987. He believed that employee ownership would reduce class conflict and improve productivity, thereby justifying the tax incentives that had been granted by Congress to ESOP companies.6

There is strong evidence, however, that the simple ownership of shares is not by itself sufficient to bring about the kind of “high performance” workplace that has evolved at United, whose employees have achieved a direct participation in the choice of top management and the running of the company that has been rare in American business and industry. The number of employees who own stock in their companies grew from about 6.5 million in 1983 to approximately 14 million, with shares worth almost $300 billion, in 1993.7 About 10 million of these workers owned their stock through ESOPs. But most of these “employee owners” have no greater influence than any other worker or shareholder on their companies’ policies or performance. Like other pension plans, ESOPs tend to be controlled by management, which may use them to further its own interests rather than those of the workers.8 During the 1980s, for example, ESOPs were frequently used by managers to frustrate hostile takeovers, since the large blocks of stock they tied up effectively kept a company out of the hands of corporate raiders.

Managerial control without worker representation also tends to limit the effectiveness of ESOPs in improving the output of workers. Jacob Javits, the late Republican senator from New York, made this point most effectively before the Joint Economic Committee in 1975. Javits said that he was “as yet unable to perceive how workers suddenly can become more productive upon the receipt of stock by an encumbered trust in which they have no voting right and no financial relationship.”9 Profit-sharing plans that pay workers a periodic cash bonus based on company profits, on the other hand, establish a more direct and immediate connection between productivity and compensation. Thus, Gordon Cain, an enormously successful leveraged buyout entrepreneur and the chairman of Cain Chemical Inc., felt it was necessary to supplement employee stock ownership in his company with a profit-sharing plan in which 10 percent of the company’s net profits were distributed to employees each quarter. The company’s president explained:

Most companies just give employees a turkey or a ham; we give them checks instead. The quarterly payments let employees know where the money is coming from. Every quarter, I would go to each plant and review its performance with the employees…. At the end of the meeting, I would hand out the checks.10

Another company whose employee relations are being seen as particularly effective is Kingston Technology in California, which announced an unprecedented $100 million staff bonus in December 1996. Kingston makes memory boards for personal computers; during the last decade its staff has grown from five to more than five hundred. From the first, it has reserved some 5 to 10 percent of its net profits for employee bonuses, which it distributes quarterly on the basis of seniority and performance. It is difficult to assess how effective Gordon Cain’s bonus policy was on worker productivity at Cain Chemical, since he assembled the company by successive buyouts and sold it within a year. It is not difficult to assess the efficacy of a similar policy at Kingston, which after ten years is still growing at a remarkable rate, with employees who seem strongly committed to the company.

Advertisement

2.

Interest in new patterns of collaboration in the workplace has been particularly strong during the past ten years, but American businesses have been experimenting with alternative labor arrangements since the early years of the Republic. The first profit-sharing plan in the United States was established in 1795, at his Pennsylvania Glass Works, by Albert Gallatin, who later became Treasury Secretary under Jefferson and Madison. A century later, during the period of “welfare capitalism,” profit sharing and stock-ownership plans were widely used to increase productivity as well as to weaken the attraction of trade unions and radical ideas. At the peak of the movement to provide such plans in the 1920s, as many as 6.5 million workers owned stock in their companies worth about $5 billion (equivalent to roughly 20 million workers and $250 billion in stock in the early 1990s).11

Welfare capitalism fell apart during the Great Depression when the economy’s collapse undermined not only corporate profits and the value of stocks, but also the optimism of many of the country’s financial and political elites. During the prosperous postwar years, workers accepted the idea of an “accord” with management, codified in most collective bargaining agreements, that conceded to the managers a free hand in running businesses in exchange for (1) employee wage gains linked to productivity improvements and allowances for increases in the cost-of-living (COLAs), (2) generous pensions and other fringe benefits, and (3) a policy basing layoffs and job transfers on seniority.

These arrangements began to break down in the early 1970s when American companies, which had largely dominated world markets during the previous quarter century, came under pressure from growing foreign competition, sharply rising oil prices, and, a few years later, the deregulation of industries such as the airlines, which increased domestic competition.12 Stagflation, the unusual combination of inflation and recession, perplexed economists and prompted Richard Nixon to impose the kinds of wage and price controls that are usually associated with Democratic administrations.

By the 1980s, lower rates of profit impelled many American companies to concentrate on improving productivity and profitability. In addition to downsizing and outsourcing, which were facilitated by new computers and other information-processing technology, American companies also began to experiment with greater employee participation. Most common were “consultative” arrangements such as “quality circles”—periodic, voluntary gatherings on the shop floor in which workers are given an opportunity to make suggestions to cut costs or improve efficiency. But some companies went further, setting up self-directed work teams and production cells in which small groups of workers have control over their work.

Many of these innovations were modeled on Japanese business practices developed by the Toyota Motor Company. The Toyota, or “lean,” production system is based on “just-in-time” inventory management in which supplies and raw materials are not stockpiled but are fed directly from the supplier to the factory floor. This requires a smoothly functioning, “defect-free” system of production. Because inventories are small, there is little margin for error, which places a high premium on having a work force that is flexible, trained in various aspects of production, and able to exercise initiative. Attention to quality becomes a normal part of each worker’s job rather than the responsibility of a separate department. Ironically, W. Edwards Deming, an American industrial engineer whose ideas were largely ignored in this country until recently, had a major part in developing the Japanese system. And its emphasis on inventory control was inspired by the practices of American supermarkets.

In Reinventing the Workplace, the economist David Levine illustrates the effectiveness of these methods in the automobile industry with the example of NUMMI, a joint venture between General Motors and Toyota that produces small cars and trucks in a former GM plant in Fremont, California. The Fremont plant had been one of the worst in the GM system, and thus one of the worst in the industry. It was plagued by alcoholism and drug use among its workers, poor quality and low productivity, and exceptionally high levels of absenteeism—on some Fridays and Mondays there were not enough workers to run the assembly line. The plant closed in 1982.

The joint venture began producing cars at Fremont in 1984. It did not introduce new technology to the old plant or try to do away with the United Auto Workers (UAW). Eighty-five percent of the company’s workers had worked in the old plant, including the leaders of the union local. Yet productivity at NUMMI was soon almost double the best levels achieved at the old Fremont plant and approximately 40 percent higher than the average GM plant, while quality, according to Levine, was superior to that of any other automobile plant in the United States. The degree of worker satisfaction, too, as measured by independent surveys, was much improved.

Among the changes made at NUMMI were a number of measures that shifted the relationship between management and workers. These have been critical to its success. First, a new contract with the UAW gave the union a formal consulting role in matters ranging from the pace of production to the company’s capital investments. The company also agreed that it would cut managers’ pay and recall outsourced work before laying off workers.

Second, job applicants were screened jointly by management and the union, and all workers received extensive training—250 hours during their first six months (compared to less than 50 hours at a typical plant) and continuing training thereafter, with an emphasis on teaching a wide range of skills.

Third, the number of job classifications was cut back to two (compared to fifty or more at a typical plant), wage differentials between them were reduced, and rotation among jobs was increased.

Fourth, workers were divided into teams of five to ten people responsible both for organizing their assigned work into respective tasks and determining how frequently to rotate among them. The team leaders, who were chosen according to an agreement between union and management, earned less than fifty cents an hour more than other workers and met regularly (about once every two weeks) to discuss ways to improve their work. Finally, bonuses were based on the plant’s efficiency and customer satisfaction.

The result was that a miserably inefficient automobile plant employing 5700 people when it closed in 1982 was transformed into one of the most productive in the GM system, with few capital improvements and largely the same work force. Moreover, by 1991, 90 percent of NUMMI’s workers said they were “satisfied with my job and environment,” as compared with 65 percent in 1985, the year after production started. The absentee rate in 1992 was less than 4 percent, less than half the GM average (9 percent) and one fifth the rate at the old Fremont plant (20 percent).13

United Airlines was also transformed by a new sense of partnership between workers and management. Although the company has benefited from favorable economic conditions and the initial enthusiasm of its workers, a factor that is particularly important in a service business, the corporate reorganization was also accompanied by changes in United’s rigid managerial style. “We’re no longer a company that operates by command and control,” GeraldGreenwald, who became the company’s CEO as part of the buyout, makes a point of saying. Soon after the reorganization, Greenwald removed the heavy glass doors that had marked off the executive offices at the company’s headquarters and set up a number of employee teams to examine the company’s operations.

In addition to the fuel-saving plan, one team recommended hiring temporary workers at $7 an hour to help unload skis during the winter, far below the $38 an hour that ramp workers earn for overtime. Another recommended giving pilots and flight attendants more flexibility to swap assignments; this helped reduce sick time by 17 percent in 1995, saving the company almost $20 million annually. And in the fall of 1995, when the company was considering acquiring US Air, a troubled carrier whose routes complement United’s, United decided not to bid in part because the employees were deeply skeptical of successfully integrating the two companies. “Not only did we not lose anything by being open,” Greenwald said, “we gained a lot.” Such worker input may keep United from succumbing to the excessive expansion that has crippled so many other airlines in the past.14

Union leaders had an important part in establishing innovative work practices at NUMMI and employee ownership at United. They have also been instrumental in arranging employee ownership at companies in the steel industry, which, like many of the automobile companies and airlines, could no longer operate profitably with the wages-and-benefits policies, work rules, and staffing levels of the 1950s and 1960s.15

In 1994, the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) had about 70,000 members who participated in ESOPs at more than thirty steel companies. Most of these ownership plans, majority as well as minority, were devised to stave off liquidation or plant closures. For example, at Algoma Steel, Canada’s third-largest integrated steel company, the union developed a bankruptcy reorganization plan based on employee ownership and participation only after the search for other buyers failed. Algoma has been run successfully by the union and management since June 1992, and its stock has far outpaced an index of steel company shares. The USWA now considers the company a model of worker-management collaboration that is “more advanced than anywhere in the world.” Nevertheless, it is reluctant to use union funds to promote and invest in employee buyouts at other companies not yet under financial duress.16

The employee buyout of Weirton Steel in 1984, the subject of James B. Lieber’s thorough report, Friendly Takeover: How an Employee Buyout Saved a Steel Town, was one of the first to rescue a threatened steel company. The employees acquired the company before the USWA acknowledged the value of such takeovers. Weirton was the largest steel mill in North America whose workers did not belong to the USWA. They belonged to the Independent Steelworkers Union (ISU), which had been formed in 1950 when the National Labor Relations Board forced Weirton to disband its company union. The ISU had no position on employee ownership.

Between 1984 and 1990 Weirton did very well under employee ownership. The company was profitable, working conditions improved, and employment rose slightly in contrast to the large declines at most other steel companies. Productivity was raised by capital improvements and by a new policy encouraging workers to exercise initiative and training them to do so. Selected employees learned statistical process control, a technique for regulating operations that was advocated by Deming. Programs of this sort are thought to have reduced Weirton’s operating costs by about $35 million by 1993.

Since 1990, Weirton has had a series of problems, few of which are unique to employee-owned companies. A major capital-spending campaign to modernize its plant, combined with the effects of the 1990-1991 recession, forced the company to cut back employment from about 8,000 workers in 1989 to 6,000 in 1994, with further cuts anticipated. To finance the capital improvements it had to sell shares to the public, diluting the workers’ stake, and scale back the employees’ share of profits. Various operating problems further increased tension between workers and management. But even so, Weirton has done well under employee ownership—much better, indeed, than many expected in 1984.

3.

The example of Kingston Technology suggests that profit sharing and worker participation can be effective in companies that are neither unionized nor employee-owned. For instance, Lincoln Electric, the country’s largest manufacturer of arc welding equipment and supplies, attributes much of its success to the system of “incentive management” it instituted in the first third of the century. Between 1934 and 1974, productivity at Lincoln rose about twice as rapidly as that of its competitors, enabling the company to maintain its leading position in the industry, ahead of much larger companies such as General Electric and Westinghouse. It also paid its workers average annual bonuses that nearly matched their base pay. In 1974, some factory workers at Lincoln earned $45,000, approximately five times the then-current median income for manufacturing workers.

The company’s labor policies are based on three key elements: almost all production workers are paid for “piecework,” that is, solely on the basis of what they produce; annual bonuses, based on profitability, are granted according to the “merit ratings” of each employee; and jobs are guaranteed so that workers won’t resist innovations that improve productivity. During the recession of the early 1980s, for example, production workers were given sales jobs instead of being laid off. (At a recent conference on “Corporate Citizenship” sponsored by President Clinton, Lincoln’s chairman criticized the business community for being too quick in letting workers go.17 )

Lincoln’s incentive scheme is reinforced in a number of ways. The company has no formal organization chart, few layers of management, and few visible distinctions between management and workers. It promotes from within and encourages communication between workers and management, both informally and through an advisory board consisting of elected representatives who meet twice a month with top management. Lincoln stock has also been sold to employees or associates of the company’s founders. By 1975, almost half the employees were shareholders.

As if anticipating the Toyota production system, Lincoln has always resisted storing raw materials or work-in-progress in a central stockroom at its plant. Instead, all materials flow directly from the receiving dock to the work station where they are to be used, and the workers at each station behave like independent contractors. “The thing I like here,” a twenty-four-year veteran said,

is that you’re pretty much your own boss as long as you do your job. You’re responsible for your own work and you even put your stencil on every machine you work on. That way if it breaks down in the field and they have to take it back, they know who’s responsible.

About 25 percent of Lincoln’s new employees quit in their first year. Some feel the meritocratic system emphasizing individual responsibility puts too much pressure on them. But few leave after that, and absenteeism is low. Although ill-conceived expansion overseas in the late 1980s has put some stress on the incentive system, average earnings in 1993 were $51,000 and some production workers earned more than $100,000.18

Many statistical studies have tried to measure the effectiveness of innovative work practices in different companies, and the conclusions are remarkably consistent: most of the significant improvements in productivity occur in companies with profit-sharing policies, not policies limited to share ownership. Among companies with profit sharing, the impact on productivity is generally greater for smaller companies, where cooperation is easier, and for firms with plans that pay a periodic cash bonus based on profits. Such bonuses are more successful in improving productivity than plans that tie pension contributions to the company’s profits. But productivity also tends to be higher when employee participation programs are combined with profit sharing and employee ownership.19

A recent study of productivity in the steel industry explains why some collaborative practices work on the shop floor and some do not. When they are used in combination, as they were at companies like Algoma, Lincoln, NUMMI, and United, such practices are extremely effective. Used in isolation, however, they are relatively weak. Specifically, the authors found that productivity was about 7 percentage points higher in those steel-finishing lines using sets of complementary practices such as (1) performance-based pay, (2) job security, (3) training, (4) worker participation in teams, (5) job rotation, and (6) systematic information sharing. However, the adoption of any one of these practices had very little effect on productivity.20

Why, then, are these arrangements not more prevalent? Economists usually view performance in the market as the most reliable test of efficiency, and since companies with collaborative work practices are relatively rare, they conclude that the costs of these arrangements must outweigh the benefits.21 But even financial markets are now known to be less efficient than they were thought to be: they often ignore profitable opportunities or are slow to exploit them.22 It seems likely, therefore, that the advantages of collaboration are great, but perhaps not great enough, or not sufficiently well known, to overcome the inertia, biases, or opposition of management, capital markets, and workers and their unions. As in a championship boxing match in which the challenger must generally be decisively better, often having to win by a knockout, dramatic and well-publicized business successes are frequently necessary to alter market perceptions and behavior.

What is clear is that management opposition to collaborative arrangements is widespread. For example, commenting on United’s employee buyout, Lee Iacocca, former chairman of Chrysler (where he was once boss of United’s Gerald Greenwald), said simply, “Somebody’s crazy. It can’t work. What do you think will happen when it’s a choice between employee benefits and capital investment?”23 Middle- and lower-level supervisors are most threatened when employees are given more independence in doing their jobs; it directly undermines their own authority, status, and sometimes their positions, and they often feel angry at being overruled or shunted aside. These managers also do not benefit much from any resulting productivity gains since they generally own little stock themselves. Another obstacle is union ambivalence or resistance. The USWA, for instance, long opposed participation by steelworkers in employee-ownership plans. Moreover, capital markets may be shortsighted in their resistance to underwriting collaborative companies.

Each of these barriers is at least partly a matter of cultural attitudes, since many of the justifications for them do not hold up to close scrutiny. Union attitudes may reflect aversion to the risks of ownership or profit sharing, risks that can be especially acute when employees’ stock is purchased with the assets of an existing pension plan, leaving the workers in the long run even more dependent on the success of a single company. However, employee buyouts have been successful in preserving jobs and can also be financed through wage concessions and borrowing against the assets of the company, leaving existing pension assets largely intact.

Since the benefits of collaboration can be substantial, and the opposition is largely a matter of inertia and of the ingrained tendencies of current business culture, limited government action could help overcome these barriers. First, it should make information, advice, and basic training in collaborative working arrangements more widely available to busi nesses, workers, unions, and the financial community, much as state and federal agricultural programs—colleges, experiment stations, and extension services—have done for farmers. Industrial programs of this sort have recently been started by both the Commerce and Labor Departments; they should be combined and expanded.

Second, laws and regulations that unnecessarily restrict experiments with worker-management cooperation should be relaxed or eliminated. For example, most workers receive health insurance from their employers because it is tax-exempt when their employers buy it but not when employees receive extra income in order to buy the insurance themselves. These asymmetric provisions of the tax code have not only limited the “portability” of health insurance, but have tended to encourage practices like downsizing and outsourcing by companies that don’t want to fund such benefits.24

Many people claim that parts of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) may inhibit cooperation between labor and management in companies that are not unionized. For example, in December 1994, the Commission on the Future of Worker-Management Relations recommended that the NLRA be clarified to insure that nonunion employee participation programs are not found to violate the act’s ban on company-dominated unions “simply because they involve discussion of terms and conditions of work or compensation.” The Commission emphasized that the law should continue to ban company unions and should make it clear that participation programs cannot be used to frustrate “employee efforts to obtain independent representation.”25 Last spring, Senator Nancy Kassebaum sponsored the Teamwork for Employees and Management Act (Team Act), a bill that tried to implement a version of the Commission’s recommendation. The Team Act was passed by Congress in July 1996 but was vetoed by the President, who said it “would undermine the system of collective bargaining.”26

This claim is silly. First, the President’s own commission pointed out that clarifying the NLRA to permit labor-management cooperation would not end its ban on company-dominated organizations that bargain with employers over wages and working conditions. Second, the main obstacle to “the system of collective bargaining” has been the steep decline of union representation, from more than 35 percent of the private-sector work force in the early 1950s to about 11 percent today, which has occurred despite the NLRA’s broad ban on company-influenced labor-management groups.27 Third, the evidence shows that employee participation programs are effective only if they are genuine and are combined with a range of complementary policies and practices such as job security, information sharing, and profit sharing. Programs introduced to co-opt or coerce workers are unlikely to improve productivity and might even make unions seem more attractive.

The Worker-Management Commission and many others have argued that the NLRA creates too many barriers to unionization and does not adequately protect workers seeking union representation. These are issues on which Democrats and labor organizations should be concentrating since unionization is the best defense against labor abuses, including coercive employee participation programs.28 But despite unions’ important contributions to worker-management collaboration at companies like Algoma, NUMMI, and United, to insist exclusively on union participation, as many union leaders, congressional Democrats, and the President have done, would severely limit the potential benefits of improved working arrangements both to workers and to the economy generally. Those benefits include not only more rapid productivity gains and economic growth, but higher incomes, and less inequality and anxiety.

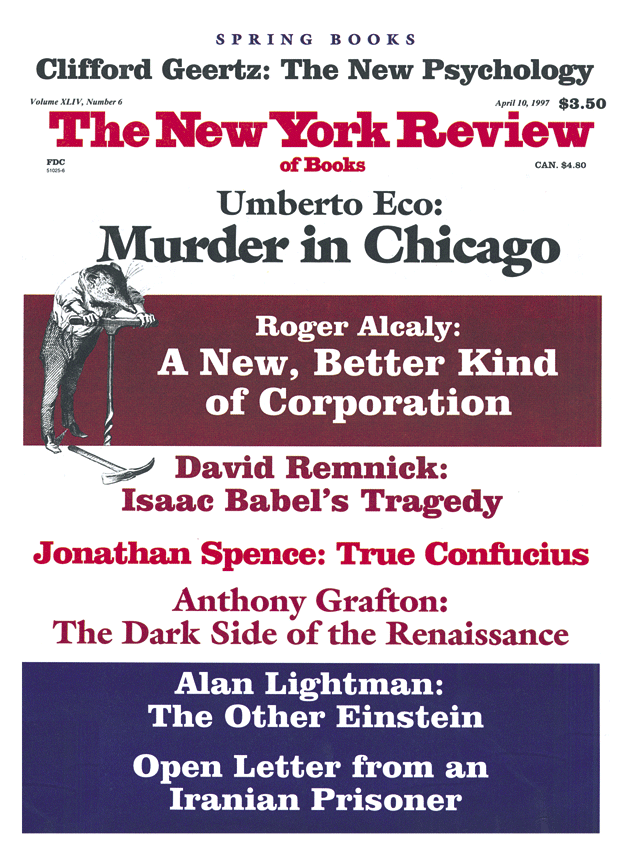

This Issue

April 10, 1997

-

1

If the Boskin Commission report is correct that the Consumer Price Index has been overstating inflation by about one percentage point a year, then average hourly earnings have actually risen by 13 percent from 1973 to 1995 instead of having fallen by 13 percent as official statistics show. Overall economic growth and growth in productivity also would be higher than we thought. For a contrary view criticizing the Commission’s conclusions as “highly debatable,” see Jeff Madrick, “The Cost of Living:A New Myth,” The New York Review, March 6, 1997, pp. 19-24. ↩

-

2

Simon Head, “The New, Ruthless Economy,” The New York Review, February 29, 1996, pp. 47-52. ↩

-

3

The flight attendants did not participate in the buyout and declined again when they negotiated a new contract in February 1996. The concessions by the three other groups—the pilots, machinists and maintenance workers, and salaried employees—amounted to about 15 percent of their wages and benefits. Of the three directorships allotted to the employees, one went to each of the three groups. These arrangements enabled the company to issue bonds and preferred stock to raise the money to buy 55 percent of the stock from the old shareholders and issue it to participating employees. ↩

-

4

“United We Own,” Business Week, March 18, 1996, pp. 96-100. ↩

-

5

Martin Neil Baily, Eric J. Bartelsman, and John Haltiwanger, “Downsizing and Productivity Growth: Myth or Reality?”, Center for Economic Studies, Bureau of the Census, Discussion Paper CES 94-4, May 1994. The best coverage of the limits of downsizing of which I am aware has been in The Economist. For example, see “When slimming is not enough,” September 3, 1994, pp. 59-60. ↩

-

6

Louis O. Kelso and Patricia Hetter Kelso, Democracy and Economic Power: Extending the ESOP Revolution Through Binary Economics (University Press of America, 1991), pp. 4-7, 51-53; and Joseph R. Blasi, Employee Ownership: Revolution or Ripoff? (Harper & Row, 1988), pp. 18-29. ↩

-

7

“Employee Ownership Fact Sheet,” National Center for Employee Ownership, Oakland, California. ↩

-

8

Mark J. Roe has recently shown how legal, regulatory, and institutional constraints have prevented pension funds and other financial intermediaries from exercising control over the companies whose shares they hold on behalf of their clients. See his Strong Managers, Weak Owners (Princeton University Press, 1994), especially Chapter 9. ↩

-

9

Blasi, Employee Ownership: Revolution or Ripoff?, p. 25. ↩

-

10

See my article “The Golden Age of Junk Bonds,” The New York Review, May 26, 1994, p. 34; and “Gordon Cain (A),” Harvard Business School Case N9-391-112, 12/6/90, especially pp. 6-7. ↩

-

11

See, for example, Stuart D. Brandes, American Welfare Capitalism 1880-1940 (University of Chicago Press, 1976), pp. 83-91; and David Brody, Workers in Industrial America (Oxford University Press, 1980), pp. 48-81. ↩

-

12

On what they call the “glory days” and subsequent decline, see Barry Bluestone and Irving Bluestone, Negotiating the Future: A Labor Perspective on American Business (Basic Books, 1992), especially Chapters 2 and 3. David Gordon shows how, during the good times, the corporate “bureaucratic burden,” the ratio of supervisory workers to total employment, rose from about 12 percent in 1948 to 18 percent by the mid-1970s. It leveled off at roughly 19 percent in the early 1980s before falling in the 1990s. See his Fat and Mean (Free Press, 1996), Figure 2.2, p. 47. ↩

-

13

Because of its low capital costs and use of the work force from the Fremont plant, NUMMI stands in sharp contrast to the Saturn Corporation, a GM subsidiary that was set up and is run in partnership with the UAW, largely through self-directed work teams. Saturn operates a large new plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee, with a work force that was sufficiently committed to its philosophy to move there. Although Saturn is a successful model of labor-management collaboration, its $5 billion cost and specially recruited work force are such obvious obstacles to replication that a contemplated second plant is likely to be a closed GM facility that uses its former work force, like NUMMI. See Gabriella Stern and Rebecca Blumenstein, “GM’s Saturn Division Plans to Build A Midsize Car to Keep Customers Loyal,” Wall Street Journal, August 6, 1996. ↩

-

14

See “United We Own,” especially pp. 98-99. ↩

-

15

See Margaret M. Blair, Ownership and Control (Brookings Institution, 1995), especially pp. 98-99. ↩

-

16

See “Changes at ASI ‘poorly understood’,” The Sault Star, June 14, 1995; and Robert Oakshott, “The United Steelworkers of America & Employee Ownership,” a Research Report for Partnership Research Ltd, London, October 1994. Oakshott writes “there is still, in the autumn of 1994, no US counterpart to Britain’s Unity Trust Bank: a majority trade union owned financial institution which is willing and able to put friendly bank finance behind employee ownership and employee buy-outs” (p. 1). ↩

-

17

Alison Mitchell, “Clinton Prods Executives to ‘Do the Right Thing,”‘ The New York Times, May 17, 1996. ↩

-

18

See “The Lincoln Electric Company,” Harvard Business School Case 376-028, 1975; and Barnaby J. Feder, “Recasting a Model Incentive Strategy” The New York Times, September 5, 1994. The company grew overseas from 5 plants in 4 countries in 1986 to 21 plants in 15 countries in 1992. ↩

-

19

See, for example, Douglas L. Kruse, Profit Sharing: Does it Make a Difference? (W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1993), especially Chapters 3 and 5; and Linda A. Bell and Douglas L. Kruse, “Evaluating ESOPs, Profit-Sharing and Gain Sharing Plans in U.S. Industries: Effects on Worker and Company Performance,” report submitted to The Office of the American Workplace, US Department of Labor, March 1995, especially pp. 16-22. ↩

-

20

Casey Ichniowski, Kathryn Shaw, and Giovanna Prennushi, “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Productivity: A Study of Steel Finishing Lines,” to appear in the American Economic Review. ↩

-

21

See, for example, Henry Hansmann, “When Does Worker Ownership Work?: ESOPs, Law Firms, Codetermination, and Economic Democracy,” Yale Law Journal, June 1990, pp. 1749-1816. ↩

-

22

See “The Golden Age of Junk Bonds,” especially pp. 29-31, and Josef Lakonishok, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny, “Contrarian Investment, Extrapolation, and Risk,” The Journal of Finance, December 1994, pp. 1541-1578. ↩

-

23

Iacocca is quoted in Adam Bryant, “After 7 Years, Employees Win United Airlines,” The New York Times, July 13, 1994. On management opposition generally, see Richard Freeman and Joel Rogers, “Worker Representation and Participation Survey: First Report of Findings,” December 5, 1994, and “Second Report of Findings,” June 1, 1995. ↩

-

24

See Blair, Ownership and Control, pp. 330-331, and Gordon, Fat and Mean, pp. 240-241. ↩

-

25

Report and Recommendations, Commission on the Future of Worker-Management Relations, US Departments of Labor and Commerce, December 1994, pp. 8-9, 13-14, emphasis added. ↩

-

26

“Clinton Kills Bill Favoring Labor-Management Teams,” Wall Street Journal, July 31, 1996. ↩

-

27

See Samuel Estreicher, “Employee Involvement and the ‘Company Union’ Prohibition: The Case for Partial Repeal of Section 8(a)(2) of the NLRA,” New York University Law Review, April 1994, pp. 125-161. ↩

-

28

See the Commission’s Report and Recommendations, Chapter 3, especially pp. 18-21; Gordon, Fat and Mean, pp. 242-245; and Estreicher, “Employee Involvement and the ‘Company Union’ Prohibition,” especially pp. 150-155. ↩