At one time or another every kid draws a mustache or eyeglasses on a portrait in a history textbook. Men are usually decorated with beads, earrings, fluffy curls, bow-tie lips, a deep, ample décolletage, and, space permitting, a crinoline. Women are provided with a five-day beard, scars, a pirate eyepatch, and a burning cigarette stuck between their teeth. My history book looked more like an illustration of the Venetian carnival than a text. This long-forgotten, thirty-year-old pleasure held nothing insidious: as I see it now, awakening sexual curiosity and awareness of the difference between the sexes drew a thirteen-year-old child into a creative game. It was all dressing up, theater, carnivalizing, the testing of borders, changing social roles.

At that age we have an easygoing attitude toward ourselves: we’re perfectly happy to be photographed with our tongues sticking out or eyes crossed. As we grow older, our relationship to our own image is more often characterized by alarm and suspicion: How fat I look there! Hide that photograph! Eventually some of us turn to direct interference with the past. (Why is this photo cropped? And whose arm is around your shoulders? Oh, that’s an old friend. We had a fight, I got mad and cut him out of the picture.) And at some point in life we realize that certain photographs (our own photos!) could be compromising evidence. We wish they had never existed. And in those shots we allow to exist, we may ask the photographer to remove the bags beneath our eyes and the shadow under our noses.

All this is the harmless mischief of private life. Who are we, after all? Just people. But what if we were tyrants with limitless power?

David King’s album of photographs opens with a large, three-quarter color portrait of Stalin by the artist Andreyev in 1922, that is, while Lenin was still alive. This very realistic portrait is at once strangely competent and inept: the artist seems to have trouble with the contours, part of the forehead seems dead, the hair glued on, the proportion of the head is wrong. But the skin, the wrinkles, the heavy Caucasus beard, which seems literally to crawl across the face like a shadow and thicken into blackness at the nose, are ably drawn. There’s no sense of flattery in the portrait, other than perhaps a bit of politeness vis-à-vis the bosses.

Here Stalin looks older than his forty-two years. He’s not yet in power, but in the expression of his eyes and mouth you can read hidden expectations and caution. Did the future dictator like this portrait? The reproduction has preserved the surprising comments of the “marvelous Georgian” (as Lenin called Stalin): “This ear speaks of the artist’s discomfort with anatomy.” And again: “The ear cries out, shouts against anatomy.” And the ear itself (an ordinary, unremarkable ear) is marked by a fat red cross!

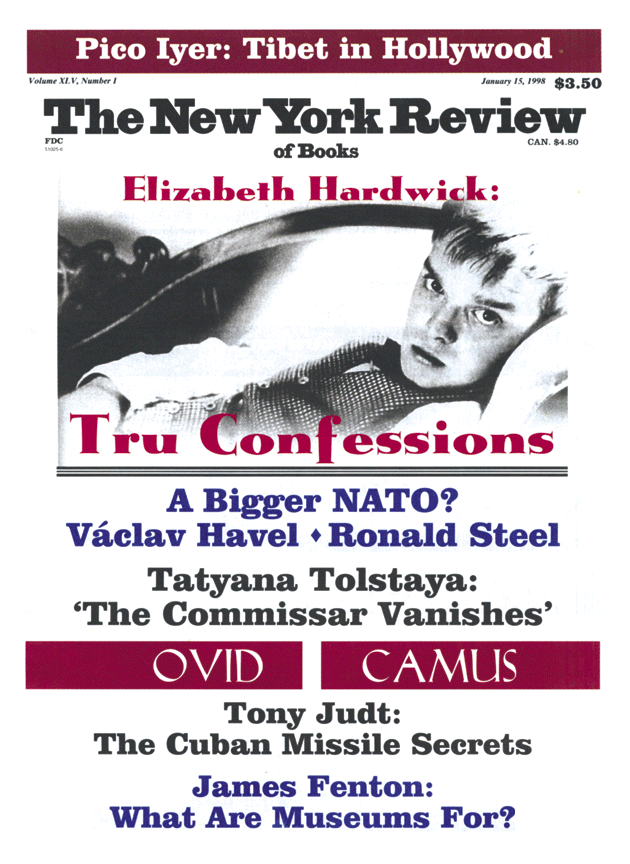

This extraordinary illustration, strategically placed at the very beginning of the album, sets the ominous tone for 192 pages of photographs, abundant historical notes, and the grim humor of the text. The album is devoted to the way in which, throughout the Soviet period, but particularly under Stalin, history in its photographic incarnation was changed, distorted, corrected, and cleaned up to the point of unrecognizability. It shows how people disappeared from photographs one by one in accordance with political necessity, leaving a hole in space, a seemingly inexplicable gap in a crowded row of colleagues.

The empty space once occupied by the disappeared person is filled either with a whitish smoke, or a black spot, or sometimes a sudden outgrowth of bushes or an unexpected antique column. Sometimes the disappeared seem to clutch at those remaining; they don’t want to fade into non-existence. And then an attentive gaze, aided by a magnifying glass, can make out here and there either an aborted shoulder (like a slight swelling on the neck of a figure left in the picture), or a knee (sticking out of the folds of someone else’s clothes), or a strange luminescence where someone once stood. And do we need to explain that the people scratched out of the photographs were just as ruthlessly and tracelessly scratched out of life, were destroyed in the Gulag, transformed into “camp dust,” in the expression of the era’s executioners? Do we need to remind the reader that their wives, children, and parents were also turned to dust?

David King has done a remarkable, meticulous job, gathering a huge photographic archive of the Soviet period consisting of originals and their many, diverse reincarnations. The Commissar Vanishes contains only a part of this archive. That the falsification of photographs under Stalin (and later, too) was an inevitable and well-established practice is a well-known fact, but when you see with your own eyes the scale and tendencies of this falsification you are struck dumb. Trotsky never existed, nor did Zinoviev and Kamenev; they didn’t participate in anything; Sverdlov never had a brother named Zinovy; Bazarov, Avanesov, Balabanov, Khalatov, Mekhonoshin, Karakhan, Radek, Bukharin, Lashevich, Zorin, Roi, Belenkii, Petrovsky, Smirnov, Rykov, Bubnov, Skrypnik, Antipov, Tomsky, Rudzutak, Peters, Yenukidze—all of them never existed. If some of these names are unfamiliar, you may well wonder why.

Advertisement

The double-headed eagle on the front of the Bolshoi Theater disappears, as does a crowd of rich peasants, entire regiments of soldiers, a crowd of thousands (glued in their place are tens of thousands bursting with revolutionary enthusiasm). Lenin didn’t spend the last two years of his life paralyzed, smiling the smile of a holy fool, but was active and healthy until his last breath. Stalin was always at his side on important trips, always present when important decisions were made; they basically worked as equals. But what are we talking about? It was Stalin who directed the Revolution and the building of the Soviet state, while Lenin just added the final touches. Like an awkward schoolboy or a loving parent, he listened to Stalin’s wise advice with interest and admiration, and was constantly amazed at the perspicacity of the Georgian genius. It’s not surprising that a passerby pointing his finger disappears from one completely innocent photograph; he seemed to be showing Stalin the right direction, but Stalin will find the road himself, thank you very much. (Are you still alive, passerby?)

People staring as the Politburo crosses the garbage-strewn expanses of Red Square disappear. The garbage disappears as well (p. 125). Nature itself becomes cleaner (after all, the Leader is passing by), is swathed in a veil of pink fog, an unseen light pours from somewhere behind Stalin’s back, the tyrant’s face glows, grows younger, his hair darkens and smoothes out, his shoulders widen, the wrinkles disappear, he grows in height and stature, as if bathed in magic milk from the source of eternal youth (pp. 146, 150, 167).

At the same time there is a series of portraits in which he seems to become not older (he acquires a slight, ennobling dusting of gray hair), but endlessly wiser, with a hint of exhaustion in the eyes (after all, he broke the back of Fascism and seized half of Europe with his own two hands) (p. 173). Finally, by his seventieth birthday he is incorporeal, immortal, and enlightened, like the Buddha. In the crossed rays of spotlights his image shines in the nocturnal Moscow sky, endlessly magnificent, in a general’s cap and epaulettes against the heavy December clouds (p. 175).

Looking at the photographs and fantastical drawings that Stalin approved (where he is wise and glowing, the most important person present), and comparing them with the originals (where he is small and cunning, pock-marked and swarthy, lost in the crowd), you can’t help but wonder about the portrait with the crossed-out ear. What was it about that ear? Why such rage, such sarcasm (he shouts and yells), such poison? The aged, rough skin, the cautious look directed inward, the darkness pouring across the face—are these mere trifles? Yet the ear, which people are not likely to notice, provoked not one but two sarcastic comments. He doesn’t understand anatomy…. Shouldn’t the artist be shot? Stalin doesn’t yet have the power to do this. But soon he will.

Ears are curious things. First of all, we don’t know our own ears, we don’t really even see them in the mirror unless we make a special effort. Second, we don’t control our ears. Unlike our eyes and mouth and hair, we can’t change them with cosmetics or mustaches or beards. Third, it’s thought that the form of the ear is just as unique and individual as fingerprints and there are branches of criminology that study ears from this particular point of view. Fourth, there’s a proverb whose meaning can be summarized as: You can recognize an animal by his ears, his ears give him away (a wolf or a donkey). King Midas has donkey’s ears! There is, in particular, a Georgian (!) fairy tale about a king whose ears turned into a donkey’s—long, hairy, animal ears, and the king hides them under a scarf. A barber, accidentally learning the king’s secret, is tormented by the desire to tell the whole world about it, but he is bound by fear and an oath. In the end, he shouts out the truth into a hollow reed; then a shepherd passes by, makes a flute out of the reed, plays it, and the flute cries out to the whole world: The king has donkey’s ears! One imagines that Stalin, with the instinct of a born tyrant, smelled an as yet unspecified danger of exposure with some animal sense, and sounded the alarm.

Advertisement

Soon he started destroying people by the millions. People turned out to be secret enemies and were eliminated; one was supposed to curse them and applaud. Why pretend that those destroyed never existed if everyone remembers that they did? Why, instead of simply settling accounts with vanquished enemies and collecting their skulls, was it necessary to make believe that the enemies had never really existed? It seems to me that besides the obvious reasons (the desire to attribute all good to oneself, elevate oneself to the status of God, and so on), the tyrant’s dark soul was troubled by mystical, irrational notions as well. There is an old rule of magic: evocation calls forth epiphanies, that is, speaking a name brings forth the spirit, the demon, the divinity; thus, God’s name must not be spoken in vain; thus, religious people speak of the devil indirectly, using nicknames; thus, in many languages the names of frightening creatures (bears, wolves, snakes) are constantly replaced with euphemisms, and they, in turn, with new euphemisms. This is the source of the ban on depicting God, and the source of blasphemy when God’s image is destroyed or distorted; this explains the jealous destruction of icons after the 1917 revolution, and their equally jealous conservation. Hence the hatred with which early Christians hammered away at the marble faces of pagan sculptures. The motivation here is not that “this never was,” but that “this will never again be,” a purge not so much of the past as of the future. Which makes it even more frightening.

This partly explains, as David King relates, why the libraries were purged not only of books by and about Trotsky but of anti-Trotskyite literature as well: titles like Trotskyists: Enemies of the People or Trotskyist-Bukharinist Bandits (p. 10) simply disappeared. In this respect, the most extraordinary material in David King’s book is perhaps the six pages (pp. 128-133) showing people in jackets, shirts, ties, but without faces; instead we see squares and circles of blackness…. The artist Alexander Rodchenko painted over the pages of a book that he himself had designed; the figures in the book (Party workers) had fallen into disgrace (i.e., they were killed by the NKVD), and therefore the artist (in fear or disgust?) ritually, symbolically, covered their faces and names with darkness.

Armed with a magnifying glass to better see the details, the reader can make amazing discoveries on his own. On pages 46-48, for instance, we see two photographs taken at an interval of perhaps 30 seconds. In one, the collar of a man’s coat is white with snow; in the other it is completely black, as if his personal weather had changed. Comparing the shots, we see that the retouchers forgot to draw the snow on his shoulders, so engaged were they in destroying the figure that formerly stood in the place of this atmospheric miracle. Often, looking for the traces of the photo censor’s awkward work, you can’t help but react as Stalin did: these hands (legs, jackets, this lighting, furniture, etc.) cry out, shout against the laws of nature! The difference, ironically, is that Stalin was infuriated by a real ear, while we are amused by artificial limbs, the product of unknown masters.

In addition to photographs, a fair amount of art is presented in King’s album as well: engravings, oil paintings, rugs, sculptures. The quality is horrible, the subjects are comic. But the laughter sticks in your throat when you remember the scale of the tragedy. This extraordinary combination of tragedy and farce, which evokes strong, mixed emotions, makes King’s album a work of art.

But what is art, and specifically, what is the art of documentary photography? And more specifically, what degree of lie is permissible in this border zone, where the artist and reality are separated for a moment by the camera lens? Another book, Eyewitness to History, is an attempt to comment on this question. It is a small collection of photographs by the Soviet photographer Yevgeny Khaldei, who worked for the TASS news agency and the newspaper Pravda (and who died this October, after the book was published). His photographs of World War II are known worldwide and have been reproduced many times, often anonymously, under the signature of Sovfoto, as the authors of the book’s biographical essay inform us. This album leaves a strange impression: it seems that its authors were torn between the idea of an anniversary gift (Khaldei turned eighty in March 1997) and an attempt to undertake an artistic study of his work, with inevitably negative results for the photographer.

If we are to believe the biographers, Khaldei’s own life is typical, tragic, and extraordinary. He was born in the Ukraine into a poor Jewish family. His mother died during a pogrom in 1918; the bullet that passed through her body lodged in the body of her year-old son. (Two decades later the Germans destroyed the photographer’s entire family: his father, grandparents, and sister.) Khaldei received only four grades of schooling; poverty forced him to go to work. Obviously a gifted artist from birth, he made his first camera himself, and took photographs from an early age. He went through the entire war with a camera, capturing extraordinary scenes, some of which he staged himself, such as the famous picture of the Soviet flag being raised over the Reichstag. Despite his significant contribution to Soviet art, he lost his job twice, in 1948 and 1976, during anti-Semitic government campaigns.

Khaldei’s best photographs are definitely from the war period. Some of them in this book have never before been published for reasons of censorship and undoubtedly have both artistic and documentary interest. This justifies the album. The shots taken before and after the war seem to belong to an entirely different person and are among the worst examples of Socialist Realism. Understanding this, and constantly justifying themselves, the book’s editors seem to be trying to lessen the photographer’s guilt by reproducing these pictures at a very small size, as if to say: no, no, this never existed! (But they did exist, didn’t they? Yes, they did, but they were verrrrry small!) These efforts and excuses are pointless: Khaldei’s pre-war photographs are marvelous in their own way and deserve decent reproduction. Looking at the extraordinary cover of lies thrown over the revolting truth of socialism the viewer sees several dimensions of reality simultaneously: the artist’s talent; the totalitarian coercion to which he was subject; and the truth that filters through the lie. The decision to publish inconvenient photographs at matchbox size reminds us of the work of the anonymous retouchers in King’s album.

Khaldei’s postwar photographs are truly awful. Here the compilers of the album, inspired no doubt by political correctness, permitted themselves to stand tall: after all, these are portraits of Rostropovich, Shostakovich, Akhmatova, Marshal Zhukov! The correct choice of subject matter is meant to justify the photographer, although these saccharine, official, dead, staged frames seem to have been done not by the lively Khaldei of the wartime storm but by his corpse, a Party zombie with no soul and empty eyes. Rostropovich, pretending to hold his bow (p. 90), is indistinguishable from the fake workers pretending to read Pravda (p. 89) in a photograph where the worker holds a copy of the newspaper, but that’s not enough for him: he enviously glances over at the copy his comrade is holding!

Congratulating Khaldei on his eightieth birthday, the authors acknowledge with some embarrassment that it never occurred to the photographer to do uncommissioned work, that he was never drawn to capturing real problems, though life presented them in abundance. For this reason the concluding words of the biographical essay, “a man of rare soul,” leave the reader somewhat perplexed. That he had a soul is without doubt; it spread its wings during the war years, and after that got lost somewhere amid the cheap cardboard and sweet-smelling glue of Soviet props.

The editors’ language adds to the awkward impression. “On October 31, they got some wine, salami, and candy, went to the registry, and then celebrated the marriage in Svetlana’s room. Soon after they had a daughter, Anna, and a son, Leonid. Svetlana died in 1986.” I think this must set a record for short descriptions of a human life. Navigation through the album is difficult, since references to page numbers are abundant, but the full-bled pages are unnumbered. The reader soon realizes that his hands are trapped: in order to look at the book the way the authors intended, he must keep all of the fingers of one hand stuck between the pages, try to turn the pages of the resulting fan with the other hand, count aloud at the same time (18, 19, 20, 21…), and, losing count, start all over again.

However, I don’t want to end the review of such a curious album on a negative note. The patient reader (as well as those endowed by nature with fourteen fingers) will find many amusing scenes in the book (and will once again remember King’s incomparable volume). Thus, for instance, on pages 60-61 (I think) one of Khaldei’s wonderful photographs is reproduced: a Russian soldier raises the red Soviet banner on the top of the Reichstag, at a head-spinning height. An officer holds him by the leg so he won’t fall. The officer is wearing a watch. After the photograph was taken and printed, the authors tell us, the censor’s careful gaze detected two watches on the officer in the original photograph, i.e., the officer had stolen at least one of the watches, and had obviously been pillaging. The watch had to be scraped off the photograph! And where did the famous red banner come from? It turns out that Khaldei, in preparation for his famous shot, prudently brought three banners from Moscow for hanging in strategic places. These banners were sewn by a friend of his, a Moscow tailor, from red tablecloths, stolen in turn from Soviet organizations. One guy hangs up a stolen tablecloth, the other holds him with hands wearing stolen watches! But the stealing doesn’t stop here: Comrade Stalin didn’t like the fact that the soldier was Ukrainian and he gave the award to other people—one Russian and one Georgian!

—Translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell

This Issue

January 15, 1998