To the Editors:

I cannot claim to be a disinterested observer of the events Ronald Dworkin comments upon in his essay “A Badly Flawed Election” [NYR, January 11]. I was counsel of record to the Florida Legislature in the two Supreme Court cases spawned by the tabulation of the vote in Florida. In our second brief my Harvard colleague, Einer Elhauge, and I presented arguments that closely paralleled the Court’s opinion as well as the concurring opinion of the Chief Justice. In spite of that involvement—maybe because of it—I readily concede that this was a difficult case with two sides. Quite unjustified, however, is Professor Dworkin’s high dudgeon and barely concealed innuendo that the Court had acted injudiciously out of a partisan zeal to protect its own agenda against future unsympathetic appointments. On the contrary, I see the Court as having reluctantly done the job its commission required of it.

In its first opinion of December 5 the Court reminded the Florida Supreme Court that its work in this matter was not solely a matter of state law (as Professor Dworkin repeatedly suggests) but that it was the Constitution (in Article II, §1, ¶2, dealing with the choice of the President) that committed the matter to the state Legislature and a federal statute, 3 U.S.C. §5, that assumed that disputes regarding presidential electors were to be resolved by rules established prior to the particular election in question. So it was a premise of that first opinion that the faithfulness of the Florida Supreme Court to the directions of the state legislature and to preexisting rules was a question of federal law and thus ultimately a proper subject for review by the Supreme Court of the United States. That opinion was unanimous. I say the Court showed a proper reluctance about becoming involved because it was at pains to achieve unanimity and because having issued its reminder, it remanded the case to the Florida Supreme Court.

The second opinion, which Professor Dworkin writes about, came a week later, when the Florida court, to which the Supreme Court had shown traditional deference, had—so it seemed to many, including three of the seven Justices of the Florida court—refused to take the hint, and come down with a decision that merits at least as much criticism as Professor Dworkin directs at the Supreme Court of the United States. True it is that the second time around the Court showed a good deal less deference to the Florida court, but that is often the case when a lower court appears to the Justices to be taking its direction in less than a wholehearted spirit.1 Thus Professor Dworkin’s repeated characterization of this being an unprecedented and unwarranted interference in a matter of state law is misleading and incorrect.

Professor Dworkin writes that it is “difficult to find a respectable explanation of why all and only the conservatives voted to end the election in this way,” and, becomingly, that “we should try to resist this unattractive explanation”: that the Court majority was acting only to protect its own radical “conservative” agenda. Professor Dworkin does not try hard enough. Instead he relentlessly casts the disagreement as one between the five “conservative” and the four “liberal” Justices, with only the former moved by partisan motives. Even if the divide were as neat as he says, one wonders why exactly the same charge of partisanship could not be leveled against the four dissenters. But in fact the divide is not at all neat. For instance, on the most bitterly contested issue dividing the Court for several decades now, the right to choose established in Roe v. Wade, two members of the majority are committed to a version of the same position Professor Dworkin espouses and the dissenters favor. Indeed, there are ideas and whole phrases in the O’Connor, Kennedy, Souter joint opinion in the Casey case that might have come straight out of Professor Dworkin’s writings. The same might be said about Justice O’Connor’s opinion in the “right to die” cases. Surely neither she nor Justice Kennedy can fairly be readily relegated to some caricaturial conservative pigeonhole. And for that matter Justices Scalia and Thomas are a good bit more “liberal” (if one must use these degraded and inaccurate labels) than Justices O’Connor and Breyer on a number of issues, such as free speech. Many commentators who share Professor Dworkin’s outrage cite, as if it proved something, Justice Stevens’s dissent saying that the Court’s decision will endanger public respect for the judiciary. But this is just the kind of thing he and Justice Scalia are sometimes inclined to say when they lose (e.g., Scalia in Evans v. Romer, the Colorado anti–gay rights initiative). Vehemence in dissent is traditional, but fouling your own nest always seems desperate.

Advertisement

Dworkin disagrees with the Court’s judgment that the kind of recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court was a denial of equal protection because it “puts no class of voters, in advance, at either an advantage or disadvantage.” But the Supreme Court has made clear—as recently as last year in a unanimous opinion in a jejune case involving one family’s sewer connection2—that disparate treatment may violate the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection even if no identifiable class of persons is the target of the intentional disparity. The Florida court had explicitly ordered a procedure to take place which treated persons’ votes in a senselessly variable manner.3 Dworkin argues that in fact there was one, general uniform standard: whether each ballot, taken as a whole, showed a clear intent to vote for one or another of the candidates for president. Discerning intent from a will or contract, a statute, or even the Constitution, taken as a whole, is a familiar and appropriate task for legal interpretation. Like Professor Dworkin, I too am a fan of hermeneutics applied to such texts. Applied by many scores of variously trained, instructed, and supervised ballot counters to punched pieces of cardboard, such a concept is manifestly out of place, to say the least.4 In such stylized settings only a stylized system will do, and that system can and therefore should be uniform. But this is, for some of the reasons Dworkin gives, a question with two sides. In the end only two Justices agreed with Dworkin, so this is hardly a cause for fulmination, dire warnings of the sort issued by Justice Stevens, or imputations of dishonestly partisan motives.

Although Dworkin finds the equal protection argument “defensible,” agreeing with Justices Souter and Breyer, he argues that the Court’s decree shutting down the election was not. The Court based its conclusion on what it discerned as the intent of the Florida law on no account to miss the December 12 safe harbor deadline, a deadline that evidently would not allow a second try by the Florida Supreme Court on that very day. This was the least convincing portion of the Court’s opinion but it too does not justify the depth of Dworkin’s or the dissenters’ scorn. They would have had the Court remand the case to the Florida Supreme Court to fashion a remedy that met the equal protection objection. But Dworkin and the two Justices who dissented from the Court’s remedy take it as a given that a recount on those terms would in any event have to have been completed by December 18, the day on which by federal law the electoral votes must be reported. But such a recount could not be completed in six days any more than in twenty-four hours. That is because that recount would go forward under the contest provisions of Florida law, and those envisage not a simple tally, but a full-blown legal process, complete with briefing, oral argument, and a full recourse to appellate process. Such contests in Florida have been known to require sixteen months. So imagine what would have happened if Dworkin’s and Breyer’s solution had been adopted. There would have been further arguments in the Florida Supreme Court on remand, followed by an opinion from that court—which may have occasioned further review in the Supreme Court of the United States. Then the recount would have taken place and there would have to have been still more process about that. If miraculously all this had been compressed into six days that fact itself would have occasioned a complaint to the Supreme Court that the Florida court had once again failed to comply with the preexisting standards of Florida law.5 Would such a continuation of the legal proceedings, inevitably leading to an indeterminate outcome, really have been more a satisfactory course? Surely if that was the alternative, the Court did well to shut the thing down then and there.

Finally, I think that the three concurring Justices, whose views Professor Dworkin does not discuss, were on sounder ground than the seven who found an equal protection violation. They argued that the Florida Supreme Court had not just interpreted some ambiguous language in the Florida statutes in a questionable way—a disagreement which perhaps the Supreme Court would have been well advised to let lie—but had turned that scheme completely on its head. Since fidelity to pre-existing Florida law is a requirement of federal law—both statutory and constitutional—such a radical departure called for correction. The argument about Florida law is intricate, but its crux—as Professor Elhauge shows in the portion of our brief for which he was principally responsible—is the Florida Supreme Court’s premise that an interpretive manual recount is always preferable to a mechanical one and that in a close election an interpretive recount must always be had even if there was no evidence of fraud or mechanical breakdown. To argue that Florida law requires such a recount whenever the outcome might be affected (that is, every close election) is to beg the question. Florida law insists that all legally cast ballots be counted, and it was the contention of the Secretary of State that all such votes had been counted, while the famous undercounts with imperfectly perforated chads were by hypothesis not legal votes.

Advertisement

But in the end all this high dudgeon is unjustified for a deeper reason. This election, as any statistician will tell you, was in effect a tie. A difference of 0.5 percent in an election in which a hundred million votes were cast—at various times, under diverse circumstances, by a wide variety of means—exceeds our present capacity for accurate tabulation. The mantra of the Gore people, that we should keep counting until we can be sure that every vote had been registered, would have brought us more and more laborious recounts, with different results from each, but no greater accuracy.6 So I agree with Professor Dworkin’s proposals that for the next time we standardize and modernize the machinery, schedule, and procedures of our presidential elections. (Such improved machinery might have seen Richard Nixon and not John F. Kennedy President in 1960, but we rarely hear that the latter’s presidency was illegitimate.) As for this election, what we saw was a range of institutions—from local canvassing boards to the Supreme Court of the United States—struggling with a freakish situation beyond the capacity of any to resolve to everybody’s satisfaction.

Charles Fried

Harvard Law School

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Ronald Dworkin replies:

In the article to which Professor Fried responds, I recommended a constitutional amendment abolishing the Electoral College and providing for the direct election of the president. Many readers warned, as I had myself suggested, that the smaller states, which have more electoral votes per citizen than the larger ones, would block that amendment because it would eliminate that advantage. But small states would not have that reason for rejecting the Uniform Model Electoral Code I also recommended, which would be offered for adoption to states one by one in return for federal financing of advanced voting machinery.

The Model Code would provide that each state’s present number of electoral votes be split among presidential candidates as near as possible in proportion to the popular vote for each in that state. If most states adopted that provision, the national electoral vote would match the national popular vote much more closely than it does now, and the risk that the winner in the popular vote would lose in the Electoral College would be much reduced. If Florida had enacted a code with that provision, then even without a recount Gore would have won twelve of the state’s twenty-five electoral votes, and would therefore have won the presidency.

Other readers expressed disappointment that I was not more critical of the

five Supreme Court Justices who made Bush president; it is disingenuous, they

said, to try to find creditable explanations for what was so obviously a crude

political decision. But the sense of legitimacy that the Supreme Court enjoys—demonstrated, once again in this case, by the fact that no one hesitated to accept its verdict even though a great many thought that verdict plainly wrong—is very important to the rule of law and principle in America, and we should not jeopardize that legitimacy out of anger at one apparently indefensible decision. It may well be, as one reader suggested, that whatever the five Justices do in the rest of their careers they will be remembered, by the public and in the academic literature, mainly for their part in this decision. But that makes it all the more important to find what I said I could not yet find: at least an ideological rationale rather than one of mere self-interest for what they did.

I therefore looked forward to the comments of Professor Fried, who was Reagan’s solicitor general and later a judge on the eminent Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, before he returned to the Harvard Law School. Fried was a coauthor of one of the many “friend of the court” briefs that urged the Supreme Court to overturn the Florida Supreme Court’s recount order. Unfortunately, his letter does not provide the defense I had hoped for, and his failure will only deepen suspicion that no decent defense can be found.

The conservative majority made two claims: first, that the Florida Supreme Court’s recount order, which specified only that ballots were to be inspected to determine the “clear intent” of the voter, violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s requirement of equal protection of the laws for everyone, because different vote-counters would interpret that abstract standard differently, and, second, that any new recount, conducted in accordance with more concrete standards, would have to be completed by December 12, which was the very day on which, late in the evening, the Supreme Court issued its opinion.7 Fried attempts to defend both of these holdings, at least in substance, and then argues that, because the election was anyway so close, it does not really matter whether the Court was right in either of them.

The equal protection clause, as I pointed out, was designed to protect people against discrimination: it condemns, not any difference in the way a state’s law treats different citizens, but only certain distinctions that put some citizens, in advance, at a disadvantage against others.8 The Florida court’s “clear intention” standard (taken from Florida statutory law) puts no one at a disadvantage even if it is interpreted differently in different counties. Voters who indent a chad without punching it clean through run a risk that a vote they did not mean to make will be counted if they live in a county that uses a generous interpretation of the “clear intent” statute; or they run a risk that a vote they meant to make will be discarded if they live in a county that uses a less generous interpretation. But since neither of these risks is worse than the other—both threaten a citizen’s power to make his or her vote count—the abstract standard discriminates against no one, and no question of equal protection is raised.9

It was a striking embarrassment for the conservative majority’s equal protection ruling that it cited not a single case in which a nondiscriminatory law had been held to violate the equal protection clause.10 In his letter, Fried cites Willowbrook v. Olech, in which the Court held that a town had denied a homeowner equal protection when it demanded a thirty-three-foot easement over her property, as a condition for connecting a water supply to the house, although it demanded only a fifteen-foot easement in the case of other houses.11 But this citation shows that he has misunderstood the problem. The town had certainly discriminated against the homeowner in that case—Justice Breyer, in his concurring opinion, noted, as important, the fact that the homeowner had alleged that the town wanted deliberately to injure her because she had sued it in another case.

Many people have said that, even if it was not unconstitutional for the Florida court to have used the abstract “clear intention” standard, rather than a more precise set of instructions about chads and indentations, using such an abstract standard was nevertheless unnecessary and unwise.12 They believe that even though the law often instructs judges and juries to determine a person’s intention with no more precise directions—to determine the intention of a deceased testator in writing the will he did, for example—such an abstract standard is out of place, as Fried puts it, “applied by many scores of variously trained, instructed, and supervised ballot counters to punched pieces of cardboard.”

But judges and juries are also variously trained and supervised, and the difference between a ballot and a will is at best a matter of degree. Indeed, it might well be harder to set out in advance sensible criteria for interpreting the visual clues on a “punched piece of paper” than for interpreting the words of a will: it might be reasonably obvious from comparing a slight depression next to the name of a presidential candidate with the much more forceful indentations elsewhere on the ballot that a voter did not mean to vote for president, for example, though very hard to formulate, in a mechanical rule, a test for the comparative force of indentations. Legislatures must often choose between the imprecision of an abstract standard, like “clear voter intent,” which risks differing interpretations, and the opposite dangers of a mechanical test that is almost certain to produce mistakes in particular cases. The claim that it is irrational to make either of these choices whenever the evidence in question is visual rather than verbal is surely wrong. Many states besides Florida, we must remember, have chosen the same abstract standard for manual recounts.

In any case, the question for the Supreme Court was not whether the Florida court’s choice of standard was wise but whether it violated the equal protection clause, and Fried has done nothing to support the majority’s holding that it did or to cast doubt on his own earlier decision, while a Massachusetts judge, upholding and applying the very standard that he now believes to violate the Constitution.13 His failure, indeed, persuades me that the majority’s decision was not even defensible, as I said it was. He next discusses the Court’s even more plainly indefensible decision that any new recount under a single standard would have had to be completed by the end of December 12 so that any new recount was therefore made impossible. Fried concedes that this critical holding “was the least convincing portion of the Court’s opinion,” and does not try to defend it. But he insists that the Court’s error made no difference because, he says, a new recount could not even have been concluded by December 18, six days later, when the Electoral College was scheduled to vote.

His judgment about the feasibility of a recount in six days is speculative: the Florida Supreme Court might well have heard arguments and declared new standards within a day or two, and it could then have ordered that new recounts proceed as expeditiously as possible, and that these recounts continue while any party who objected to the new standards appealed to the Supreme Court yet again. In any case, however, it would have been wrong for the Court to prejudge the question whether a December 18 deadline could have been met. Florida already had a slate of electors pledged to vote for Bush, and they would have voted for him on that date if the recount had not been completed. If it were completed after that date, and showed that Gore had actually won, then a rival set of electors might have sent their votes to Congress, and that body would then have decided whose electoral votes to accept. That is the procedure the Constitution specifies, and the Court had no right to subvert it.

Fried next suggests that the strongest argument for what the Court did was one that in fact appealed only to the three most conservative justices, Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas. They said, and he agrees, that the Florida Supreme Court did not simply attempt to interpret Florida law, as it had a responsibility to do, but instead radically revised it. The Florida statute provides, as one ground for contesting an election, that the certified count has rejected a “number of legal votes sufficient to…place in doubt the result of the election.” The key question is whether that provision permits a court to order a manual recount to determine how many of the ballots that the vote- counting machines had rejected because of imperfect perforation actually demonstrated a clear intention to vote for one candidate or the other. Fried’s brief argued (relying mainly on a debatable interpretation of provisions governing not the challenge stage of a post-election proceeding but the earlier protest stage) that the Florida statute assumed “by hypothesis” that imperfectly perforated ballots were not legal votes, so that the Florida court “begged the question” by assuming that a manual recount of such ballots was permissible even in a challenge proceeding.

But the Florida court’s contrary interpretation is surely, at a minimum, defensible. That court attributed a perfectly sensible purpose to the challenge provisions of the statute: those provisions aimed, it supposed, to ensure that machine limitations should not change the result of a very close election by rejecting ballots that were legally cast and showed a clear intention to vote. That interpretation is attractive in itself and fits comfortably into the contest part of the Florida scheme, where success requires showing that the alleged error would have changed the overall result. Bush’s own witness in the contest trial, John Ahmann, admitted that the machines used to tabulate punch-card ballots, which he had helped design, often make mistakes, so that manual recounts are desirable in close elections.14 If we accept that understanding of the statute’s purpose, such ballots are indeed “legal votes,” and it is Fried, not that court, who begs the question. He and his colleague, Professor Elhauge, may think their own interpretation better. But they have no basis for the extraordinary conclusion that the Florida court’s interpretation was so demonstrably wrong as not to count as an interpretation at all.15

Fried’s closing observations are unfortunate. He says that it does not really matter whether the Supreme Court’s decision was defensible because the election was so close anyway that it might as well have been Bush. He treats the fact that five of the nine Supreme Court justices are political conservatives as, in effect, a tie-breaker like a coin flip. But it will make a very great difference to people everywhere that it is Bush rather than Gore who is America’s president. Bush’s cabinet appointments (which include, as attorney general, John Ashcroft, the candidate of the religious right) have already refuted the optimistic assumption that he will try to govern from the middle, and there is ample reason to worry that his future Supreme Court appointments will be equally aimed at pleasing the extreme right of his party.

When a presidential election is close, particularly when so much turns on the outcome, it is more and not less important that the rules in place be followed punctiliously in deciding who actually won. If Gore has won not only the national popular vote but the popular vote in Florida, and hence the Electoral College, as well, then it is not only unfortunate that we will be governed by Bush’s policies and constituencies, but unfair. Florida’s vote-counting machines, many of which are conceded to be inaccurate, particularly in counties with a high proportion of minority and poor voters, declared 3 percent of the state’s ballots non-votes. (The average in the rest of the country was 2 percent.) Fried insists that it is beyond “our present capacity” to achieve a more accurate tabulation. But the careful unofficial recounts now being conducted separately by The Miami Herald and by a group of other prestigious newspapers, which Fried declares a foolish exercise, will presumably show that his surprising pessimism is unfounded.

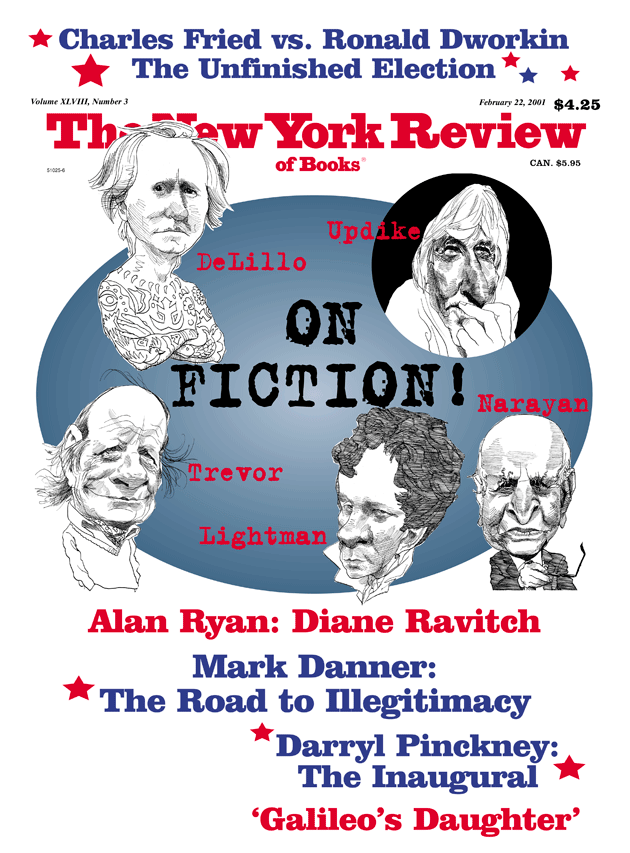

This Issue

February 22, 2001

-

1

I offer only one example, but there are many: in 1992 in the Harris case, the Supreme Court in one night set aside three stays issued in a death case by the Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit, and finally ordered that court to issue no more stays without permission of the Justices. ↩

-

2

Village of Willowbrook v. Olech, 120 S. Ct. 1023 (2000). ↩

-

3

That this variable method was sanctioned after the election had taken place, and when it was reasonably thought by the Bush forces to favor their opponent, makes the Florida court decree more, not less, offensive. ↩

-

4

Thus, for instance, some counters would decide whether an indentation was meant as a vote from whether it appeared next to the name of the presidential candidate of the same party as candidates for other offices for whom that voter had unambiguously voted. This is not an absurd inference in a forensic exercise or if doing history. I suggest that as a way to determine an election it is absurd, although as a Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts I participated in just such a process in the Delahunt case. ↩

-

5

I am glad Dworkin does not make anything of two frequently heard specious arguments. It is said that not even December 18 was a true deadline and that Florida might have delivered its vote right up to the January date when the electoral votes are counted in Congress. Support for this is drawn from Hawaii’s having once reported its votes well after the December deadline, but that was in an election where nothing turned on the Hawaii votes. Others have also complained that by stopping the recounts that were then in progress the Court created the very impossibility which they urged to justify their conclusion. This is nonsense. Assuming, as this complaint does, the equal protection violation, the recounting halted by the Court was invalid and would have had to be repeated in any event. ↩

-

6

The tabulation now underway by various news media, assisted by national accounting firms, is for this reason a particularly foolish enterprise. ↩

-

7

Fried objects to my description of all five of the Justices in the majority of the Court’s decision as “conservative” and the four dissenters as “more liberal.” I agree that the opinions of Justices Kennedy and O’Connor are less predictable than those of Justices Rehnquist, Scalia, and Thomas, and I have praised decisions of the former Justices about, for example, abortion and homosexual rights in past articles in these pages. See Chapter Four of my book Freedom’s Law (Harvard University Press, 1996) and Chapter Fourteen of my Sovereign Virtue (Harvard University Press, 2000). But the large and growing number of 5–4 Supreme Court decisions, in which the five Justices I called conservatives have united, justifies my informal description. ↩

-

8

I describe the contemporary debate among judges and scholars about the correct interpretation of the equal protection clause in Chapter Fourteen of my book Sovereign Virtue. All sides to that debate have agreed that the clause only condemns differences that discriminate against someone. ↩

-

9

It is, I think, arguable that Florida’s use of markedly more inaccurate vote-counting machines in some counties than others denies equal protection to those in the former counties, particularly since those are counties with a higher proportion of minority and poor voters. But that holding would have benefited, if either candidate, Gore rather than Bush. ↩

-

10

It was also a striking embarrassment that the conservatives found it necessary to declare that their bizarre interpretation of the equal protection clause “is limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.” It is of the essence of the legal process that decisions be based on generally applicable principles, and the remarkable statement that this decision would be precedent for no future ones seems almost a confession that the majority’s equal protection argument was a bad one. ↩

-

11

The Court properly held, in that case, that the equal protection clause protects single individuals as well as groups from discrimination. ↩

-

12

As many commentators have noted, and as Fried’s comments about the impermissibility of courts setting electoral standards not already in the state statutes suggest, the Florida court had reason to fear that if it did specify more precise standards for a recount than the Florida statute stipulated a Supreme Court majority would have overruled it on that ground. ↩

-

13

See Delahunt v. Johnston, 423 Mass. 731 (1996). In that case, which Fried mentions in his letter, he agreed, as a member of the court, that “if the intent of the voter can be determined with reasonable certainty from an inspection of the ballot…effect must be given to that intent….” He and the other judges understood that different inspectors would interpret that standard differently—they themselves arrived at a vote count different from the total the lower court judge had reached—but gave no suggestion that any of them detected the slightest equal protection problem in endorsing that standard for all Massachusetts elections. ↩

-

14

Mr. Ahmann had written in a patent application that “incompletely punched cards can cause serious errors to occur in data-processing operations using such cards.” See David Barstow and Dexter Filkins, “For the Gore Team, a Moment of High Drama,” The New York Times, December 4, 2000, p. A1. ↩

-

15

Another reader, Robert Lochner, suggested that the three-judge concurring opinion, which he agrees was based on unacceptable premises about the Florida statute, can only be understood as manifesting a lack of trust by those Justices in the Florida judicial system. He may be right—as he points out, Justice Stevens in his dissent made the same suggestion—but that distrust does not provide even an ideological defense of that opinion, because the deference that those three Justices have consistently argued is owed to state decisions supposedly extends to state judicial as well as to legislative and executive officials. ↩